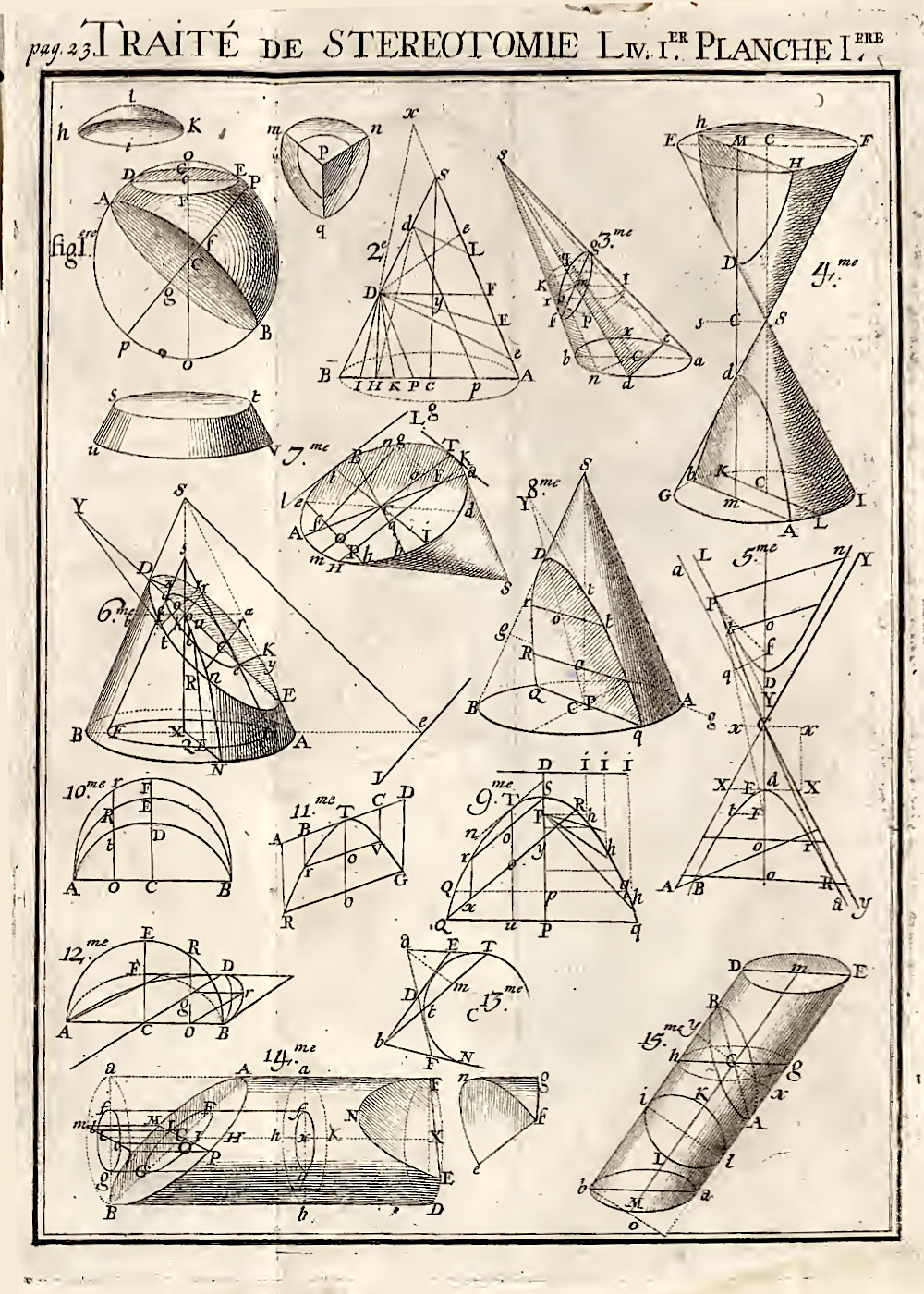

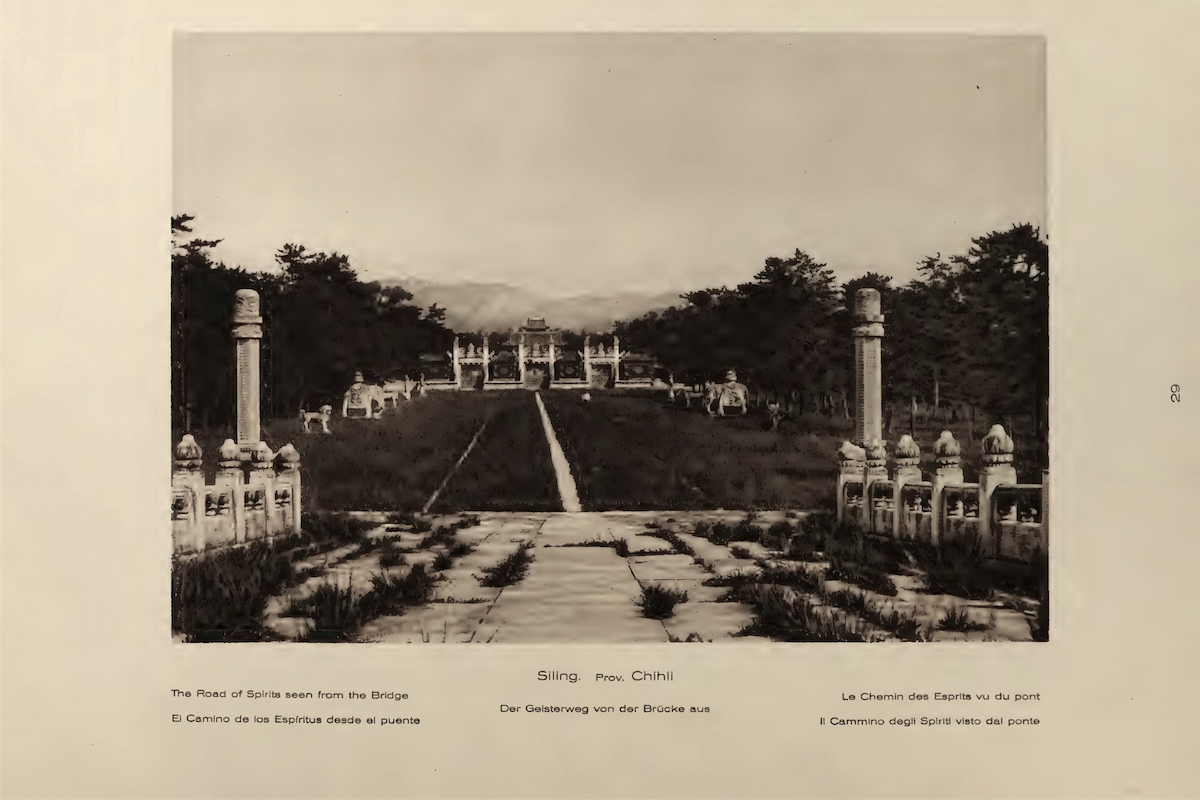

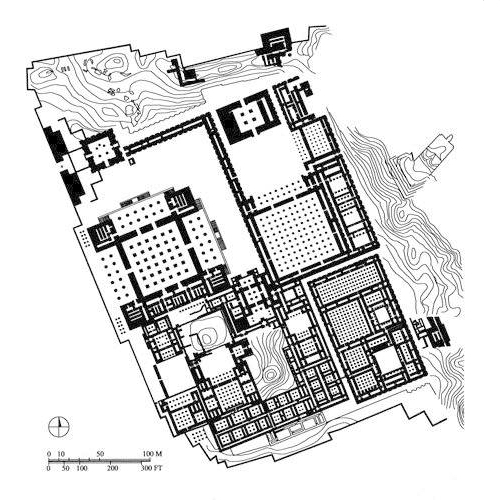

Ernst Boerschmann: The Road of Spirits seen from the Bridge, Siling, from Picturesque China (New York 1923)

Now known as the Sacred Way, Thirteen Tombs of the Ming Dynasty, Beijing.

What did Lúcio Costa think of China?

It is beneficial, from time to time, to go back to what architects themselves thought was on their minds when they were working on a project. This often has to be taken with a pinch of salt, as architects will invariably use this as an opportunity for self-aggrandisement. It also serves as a counterpoint to self-aggrandisement by academic historians. There is no reason to suppose that Lúcio Costa had any interest in self-aggrandisement, however, despite his achievement, as he was notoriously modest. He was possibly the first living architect to have his work recognised as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO - not one but three - the urban plan for the new city of Brasília (1956-60), the restoration of the ruined 18th century Jesuit churches and new museum at São Miguel das Missões, Rio Grande do Sul, and the restoration of the 18th century town of Ouro Preto, Minas Gerais. He beat his friends Oscar Niemeyer and Roberto Burle Marx to the list (both came later), although he should share Brasília with both.

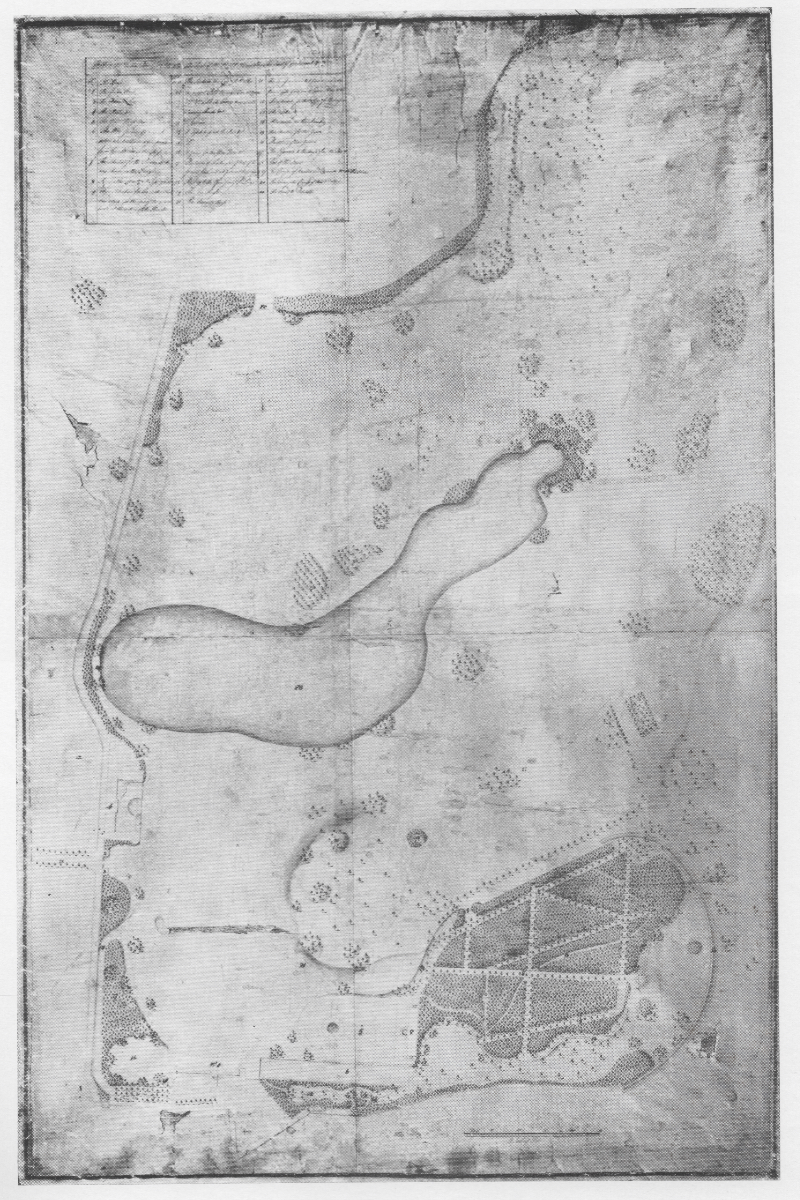

One curious and overlooked source claimed by Costa in his later reflections on his design for Brasília - “Ingredientes” da concepção urbanística de Brasília was:

which could be translated as:

The fact that I then became aware of the fabulous photographs of China at the beginning of the century (1904±) - embankments, retaining walls, pavilions with site plans - contained in two volumes by a German whose name I have forgotten.

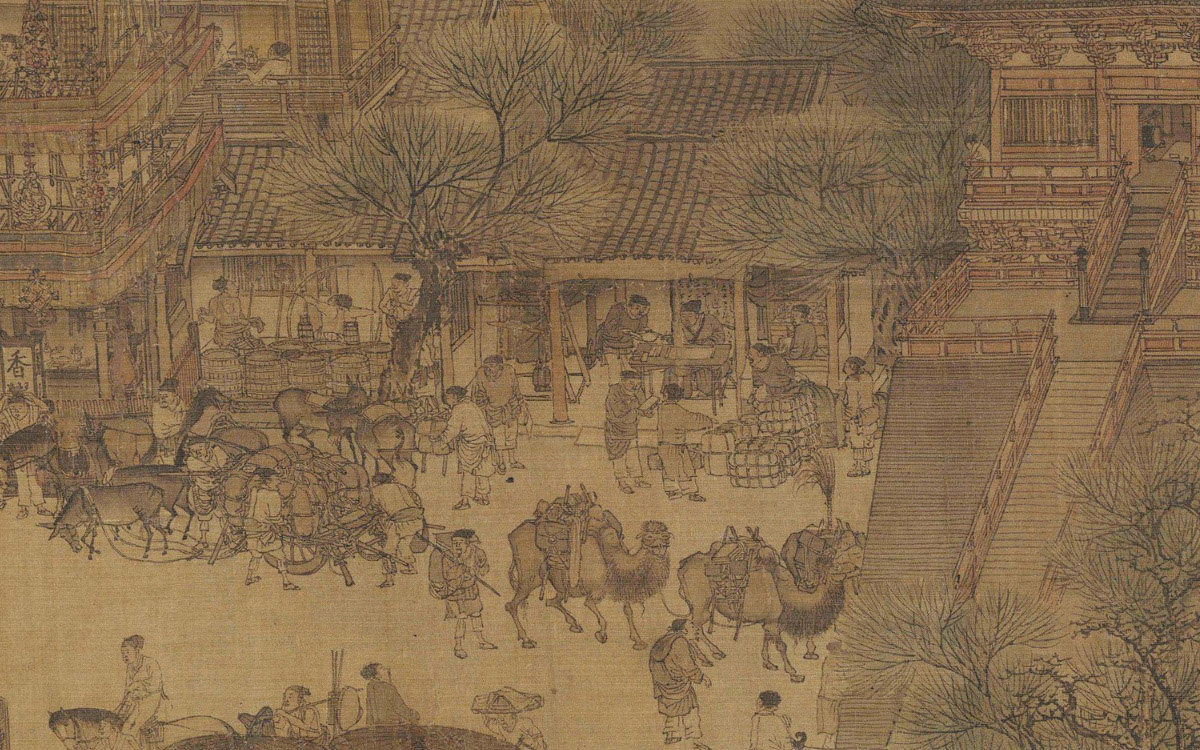

Zhang Zeduan: Scenes Along the River During the Qingming Festival (early 12th century)

This detail from the scroll painting Scenes Along the River During the Qingming Festival by the artist Zhang Zeduan represents not only the artistic accomplishment of the Song dynasty but also the vitality of life in Chinese cities in this period.

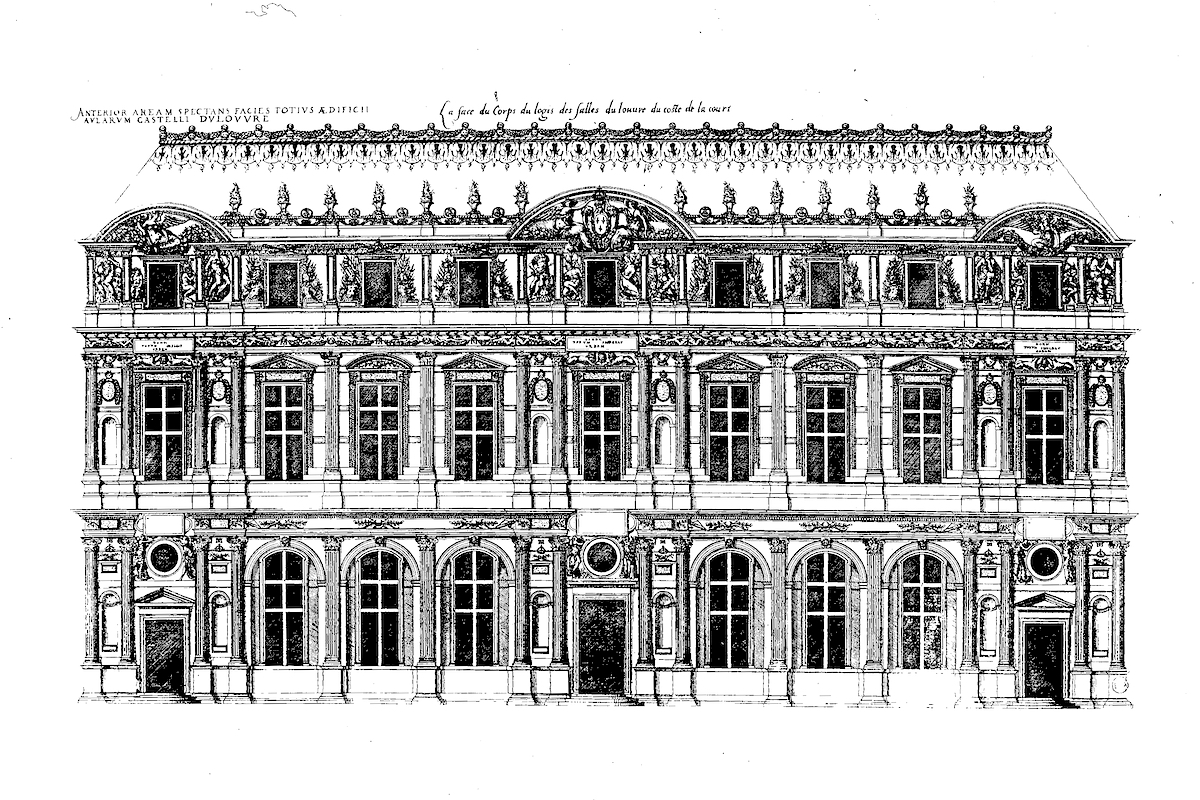

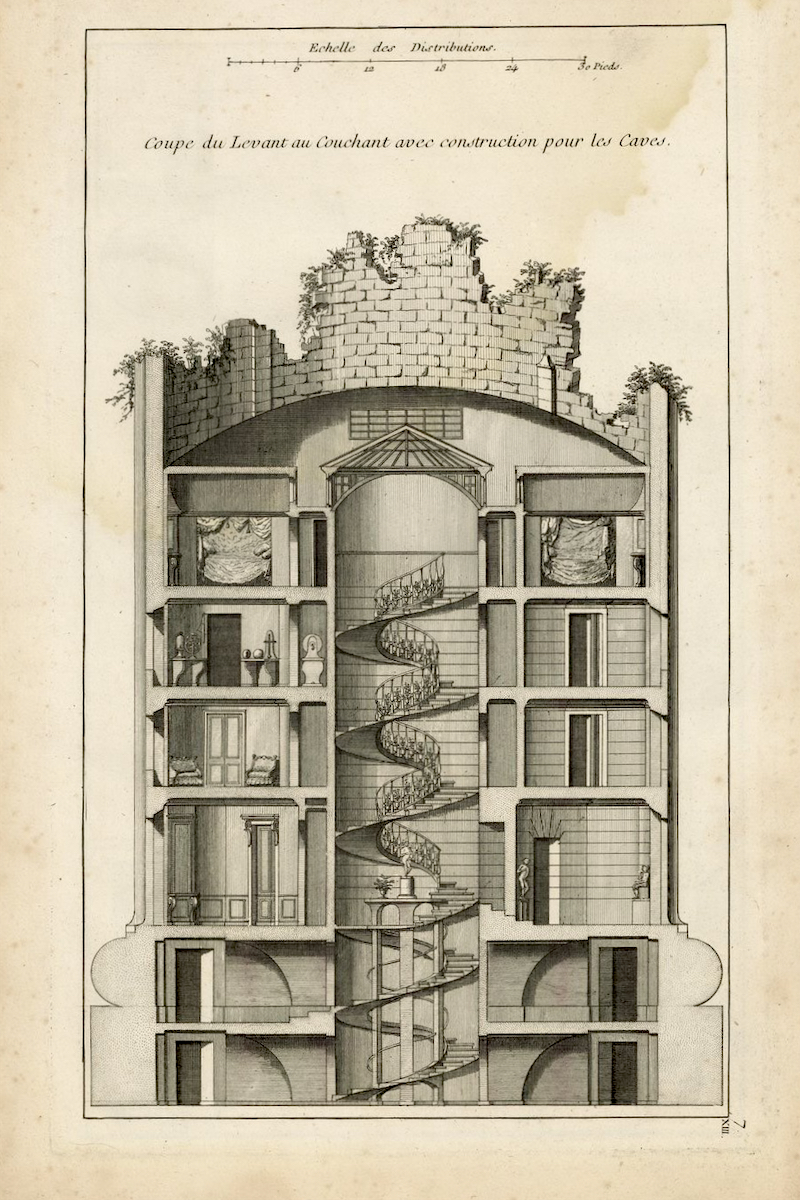

Lúcio Costa was in fact pondering the same loss of vernacular culture in the face of Modernity in Brazil as was China. Despite his persona as a hard-line Modernist - he was project leader on the

Ministry of Education Building in Rio de Janeiro (1936-42, although Oscar Niemeyer was the more important designer) - he continued to work on many projects in a vernacular mode or mixing vernacular and Modern elements, such as at São Miguel das Missões.

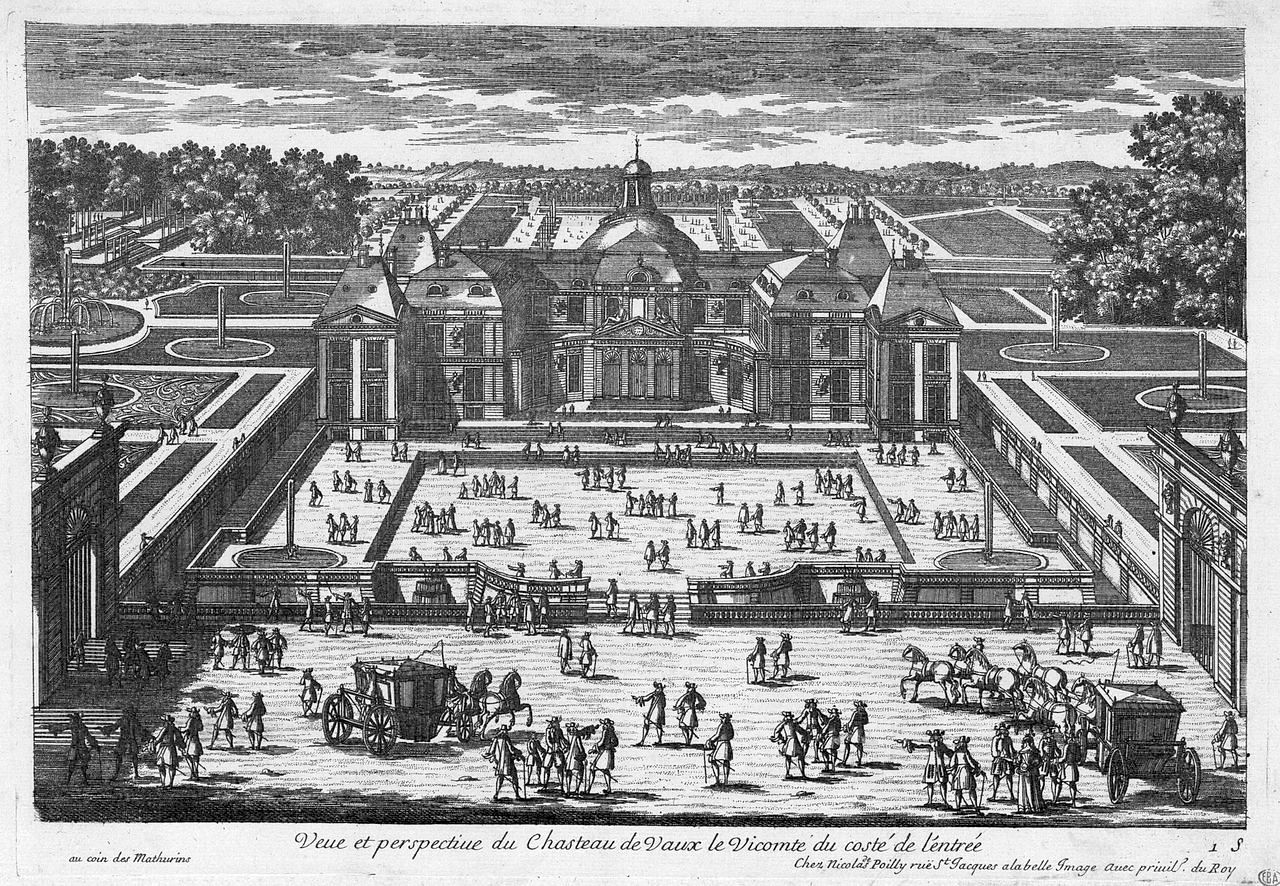

Lucio Costa: Apartment in Leblon, Rio de Janeiro (c. 1936-c.1960)

© Thomas Deckker 1989

Lucio Costa built this block of apartments in Leblon following his appointment as architect for the Ministry of Education Building, Rio de Janeiro (1936-42), and took the rooftop for his own family. It reflects his wide range of interests as not only a successful architect and urban planner but also Director of the Serviço do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional [National Historic and Artistic Heritage Service].

Boerschmann's Chinesische Architektur was published in many editions besides the deluxe 2 volumes by Wasmuth in Berlin in 1925. The rare Wasmuth edition (of which there is a copy in the National Art Library at the Victoria and Albert Museum) was in a large format with very high quality printing. Unfortunately I have not been able to locate a scan of this edition. However scans of the more popular Picturesque China are easily found, as is the book itself. I am not sure if Boerschmann would have approved of his study being valued for being 'picturesque', but any survival is good thing.

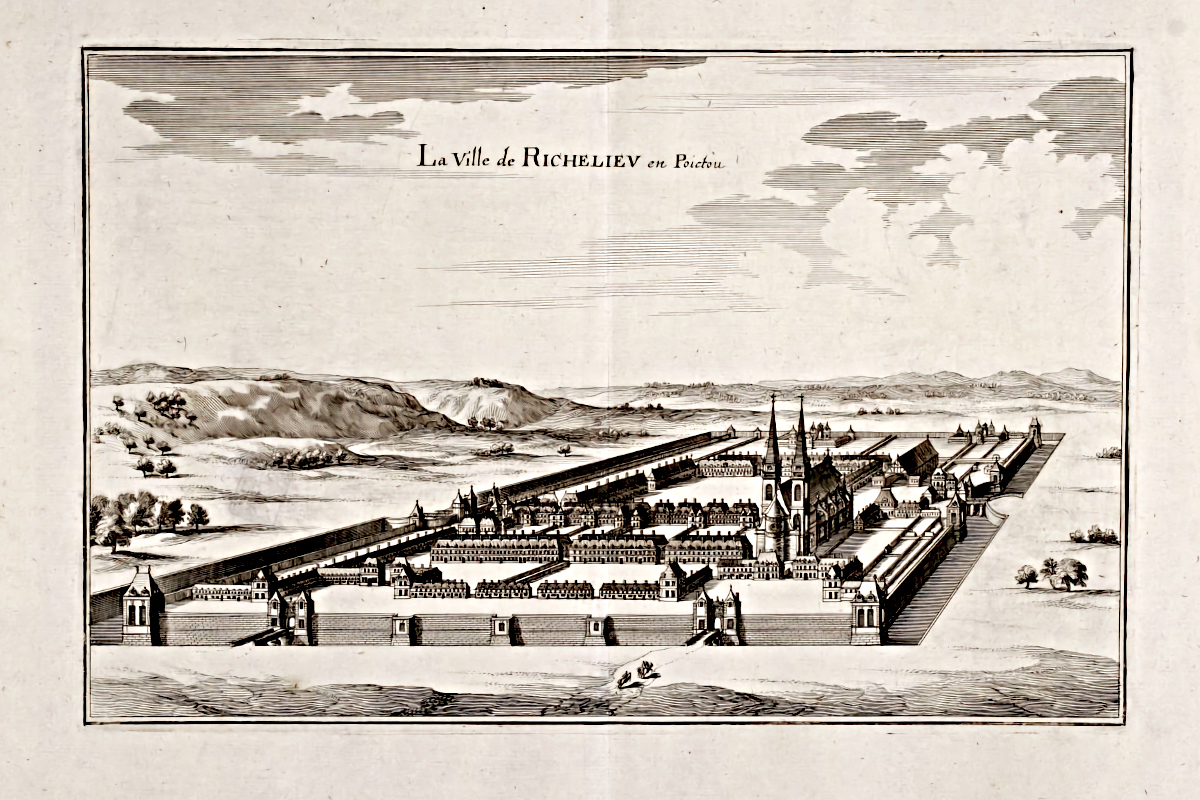

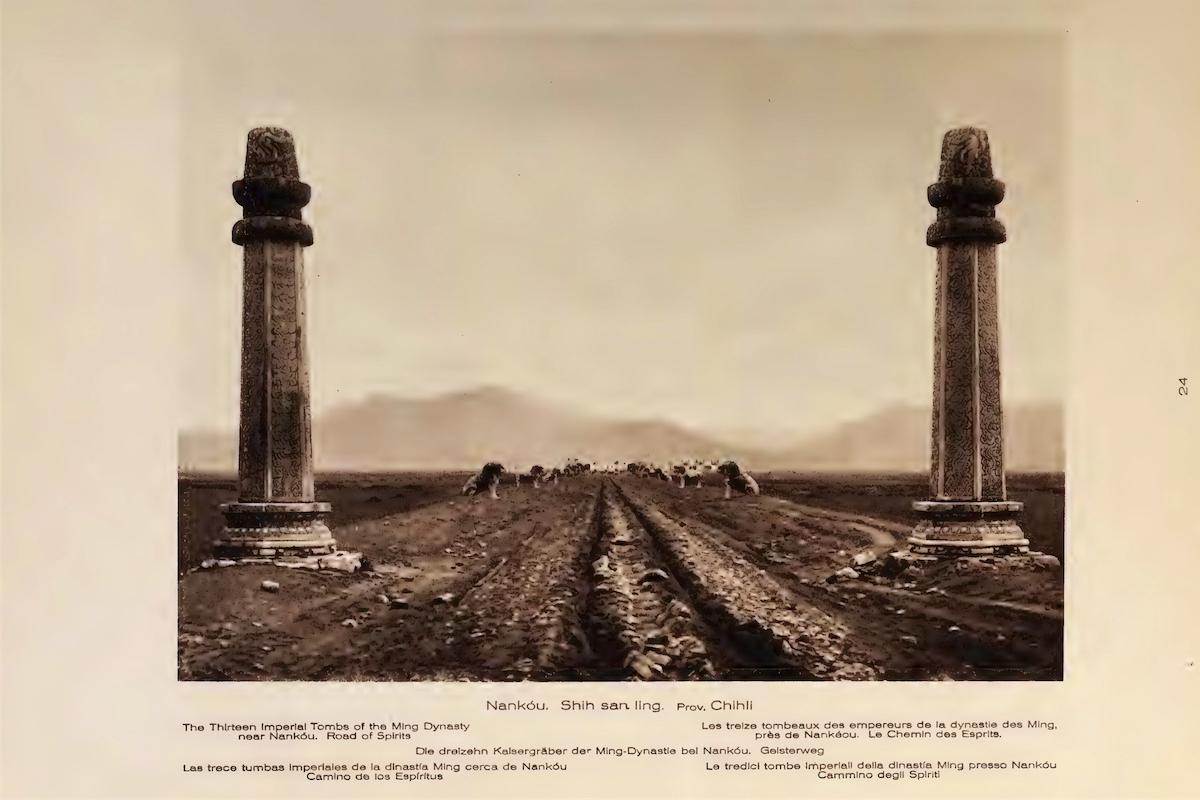

Ernst Boerschmann: The Road of Spirits in front of the Tomb Temple, the Western Imperial Tombs of the Manchu Dynasty, Siling, from Picturesque China (New York 1923)

Now known as the Western Qing Tombs, Hebei Province.

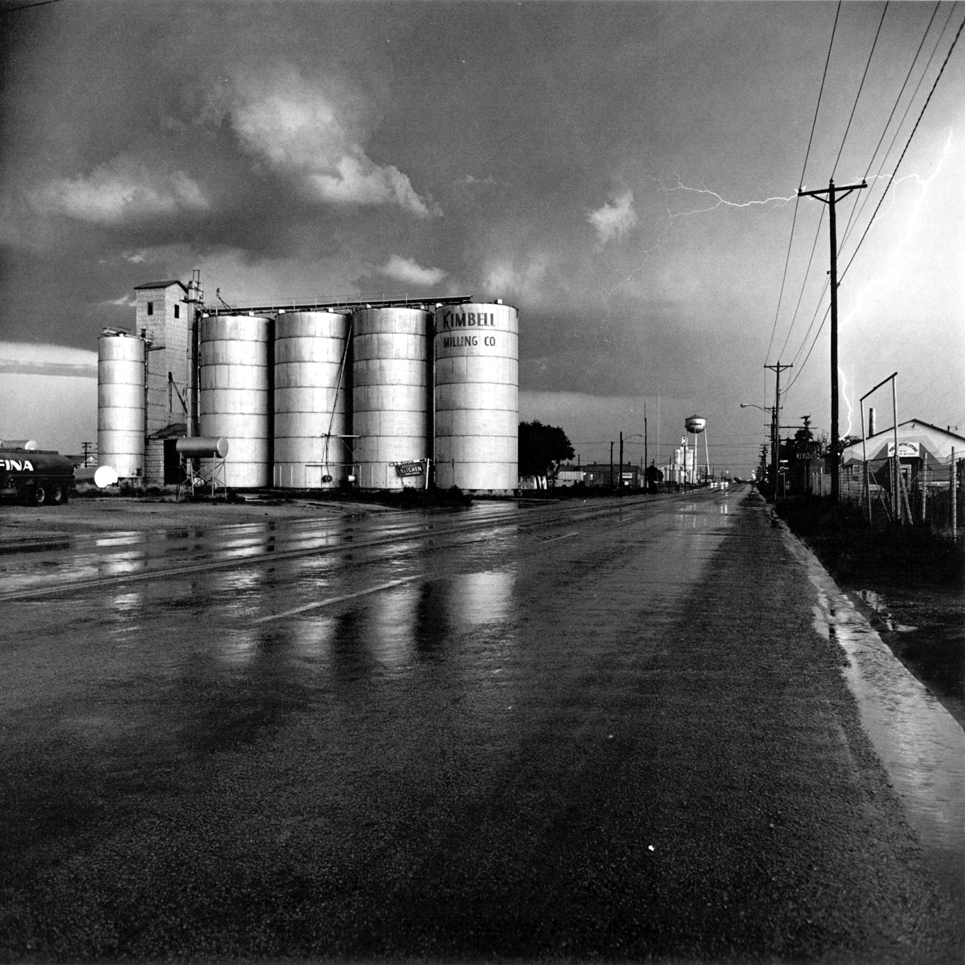

Ernst Boerschmann: The Road of Spirits at the Thirteen Imperial Tombs of the Ming Dynasty, near Nankou, from Picturesque China (New York 1923)

Now known as the Sacred Way, Thirteen Tombs of the Ming Dynasty, Beijing.

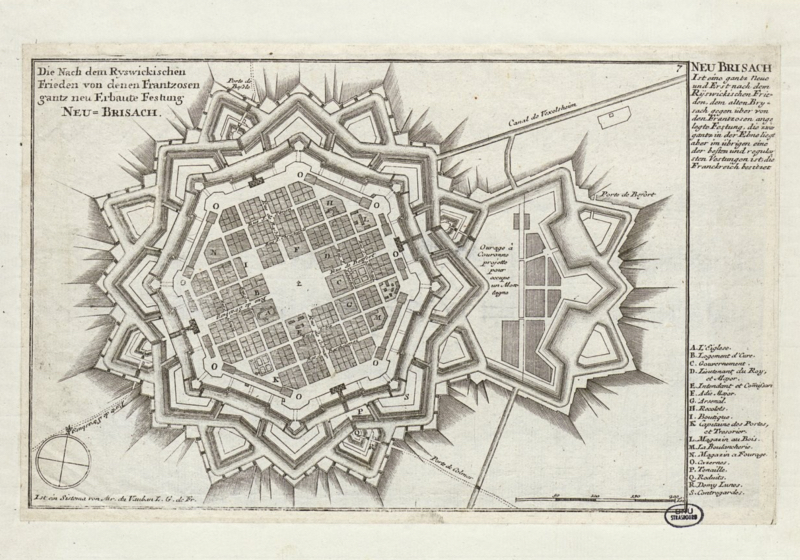

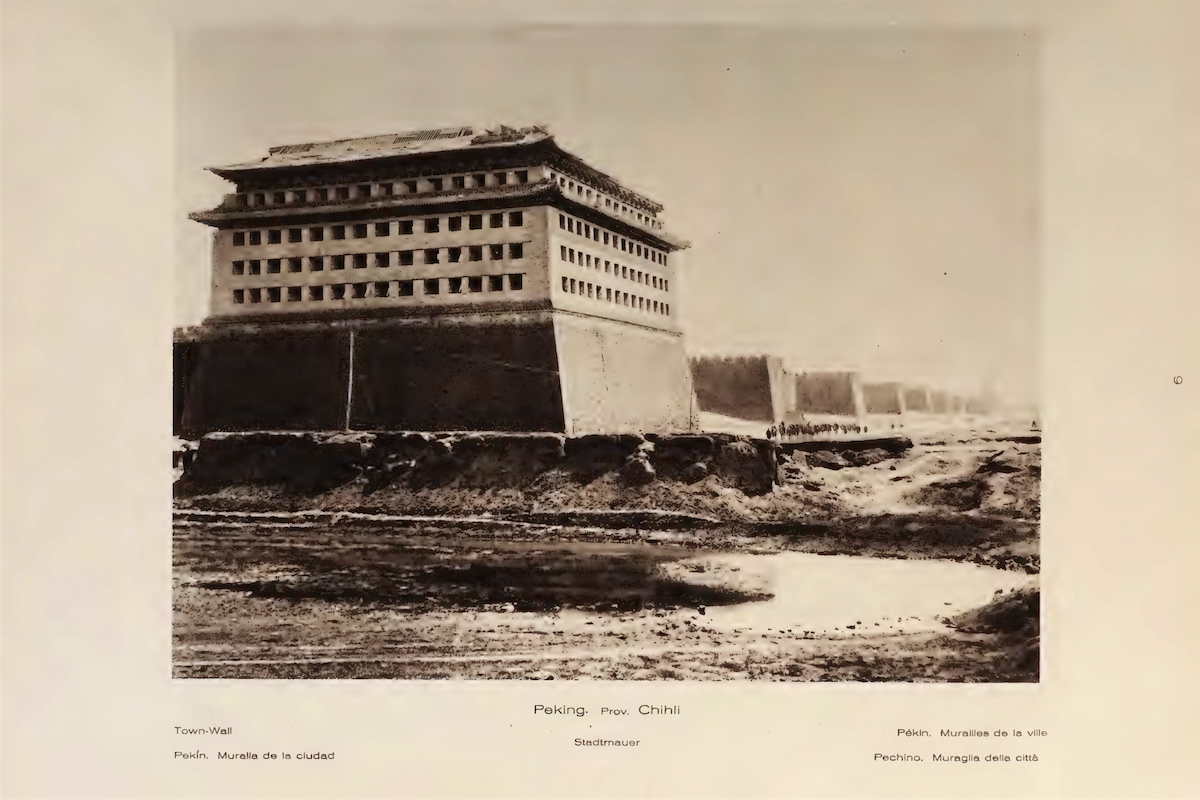

Ernst Boerschmann: Town Wall, Peking, from Picturesque China (New York 1923)

Destroyed, Beijing.

Its easy to see what Lúcio Costa appreciated in these photographs, and for the avoidance of doubt he tells us: "embankments, retaining walls, pavilions with site plans". As an architect Boerschmann was interested in the formal and abstract, rather than the picturesque, and particularly the relationship of building to landscape. There is a sense of abandonment, of melancholy, which suits the Brazilian mood of saudades.

Footnotes

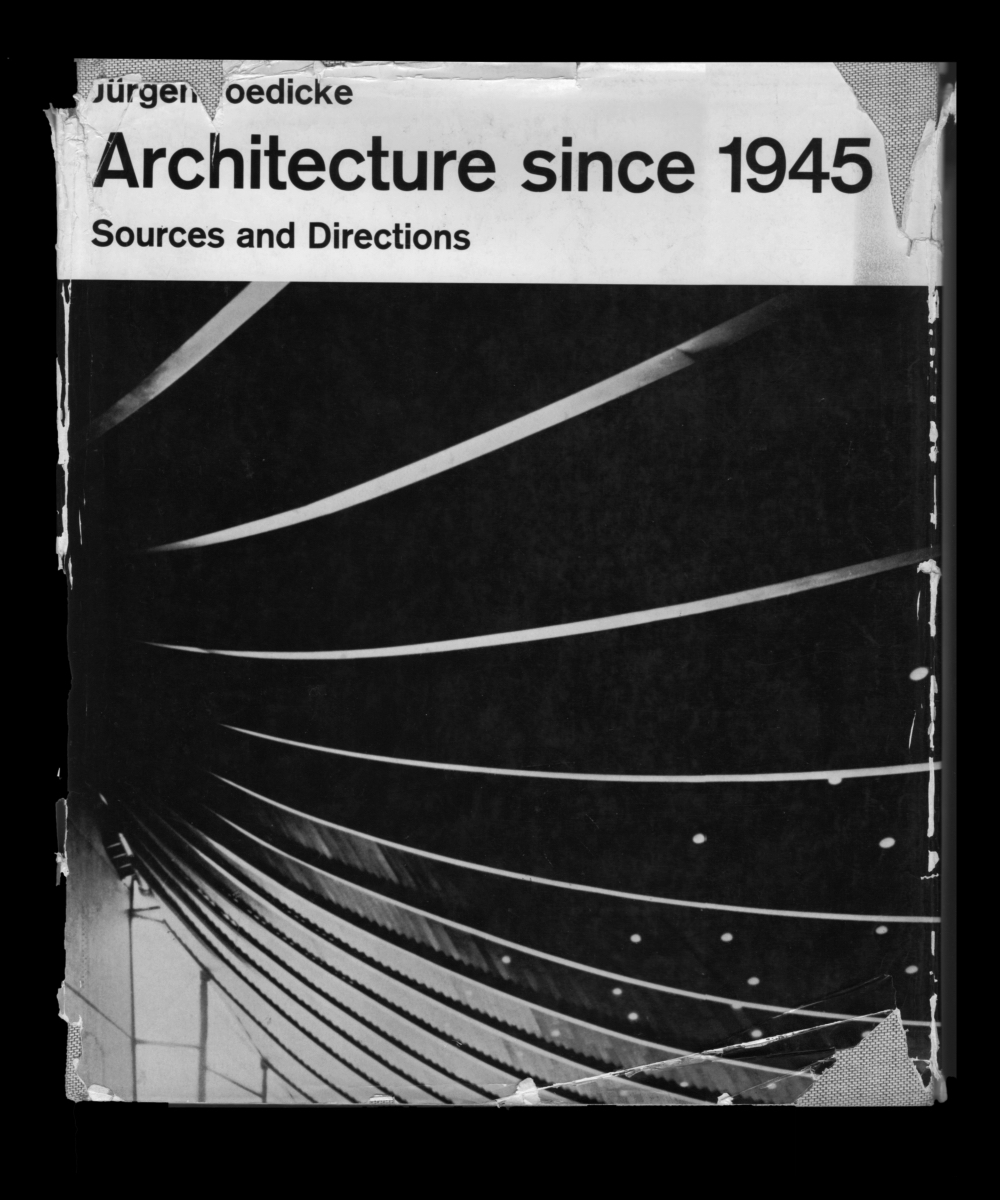

Wasmuth

Wasmuth was a famous publisher on architecture: two of the most famous and influential works were

Das Englische Haus (1904) by Hermann Muthesius and

Ausgefuhrte Bauten und Entwurfe (1911), the first publication ever on Frank Lloyd Wright. Both of these were of course on Arts and Crafts architecture, the period claimed by Modern architects as the transition to Modernism, a claim equally vehemently denied by the Arts and Crafts architects themselves.

Chinesische Architektur was part of a series on world architecture published by Wasmuth,

Orbis Terrarum, which included a volume on Britain (1926) by the distinguished photographer

Emil Otto Hoppé. The Britain depicted there is as remote as Boerschmann's China.

Thomas Deckker

London 2024