thomas

deckker

architect

critical reflections

Neuf Brisach: The Art of War

2022

2022

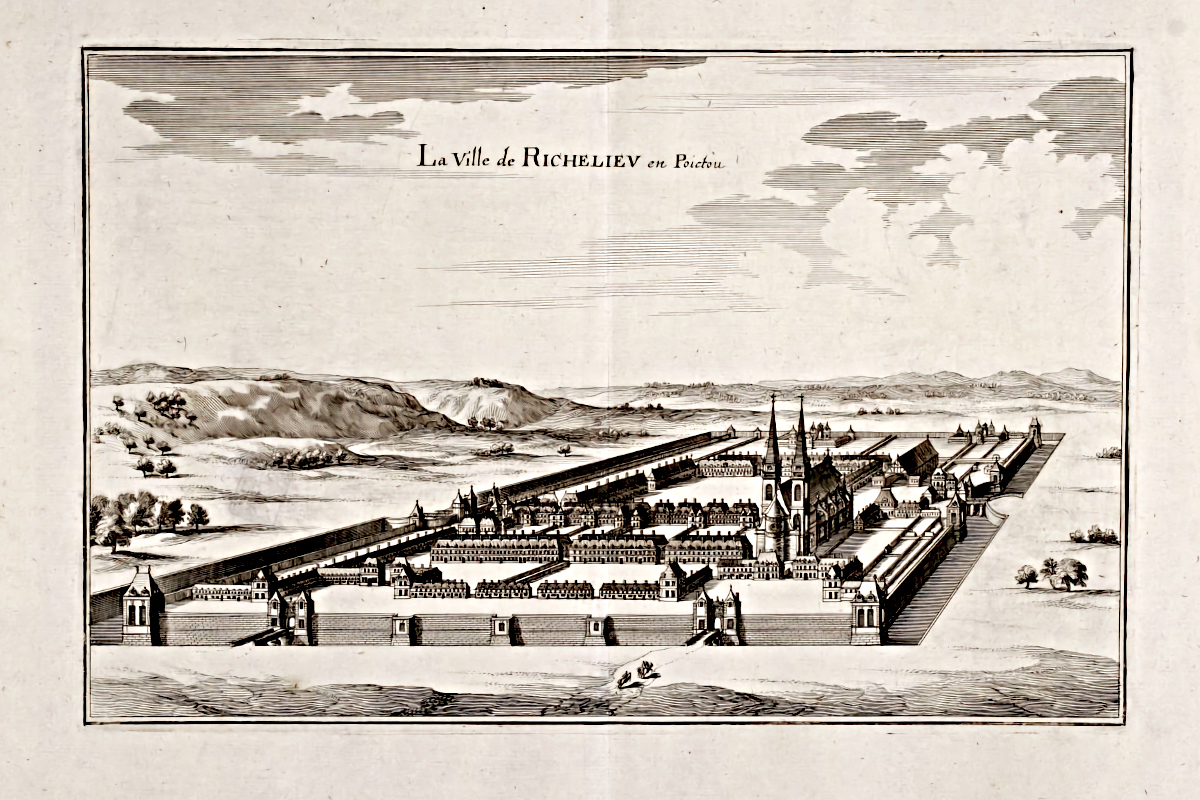

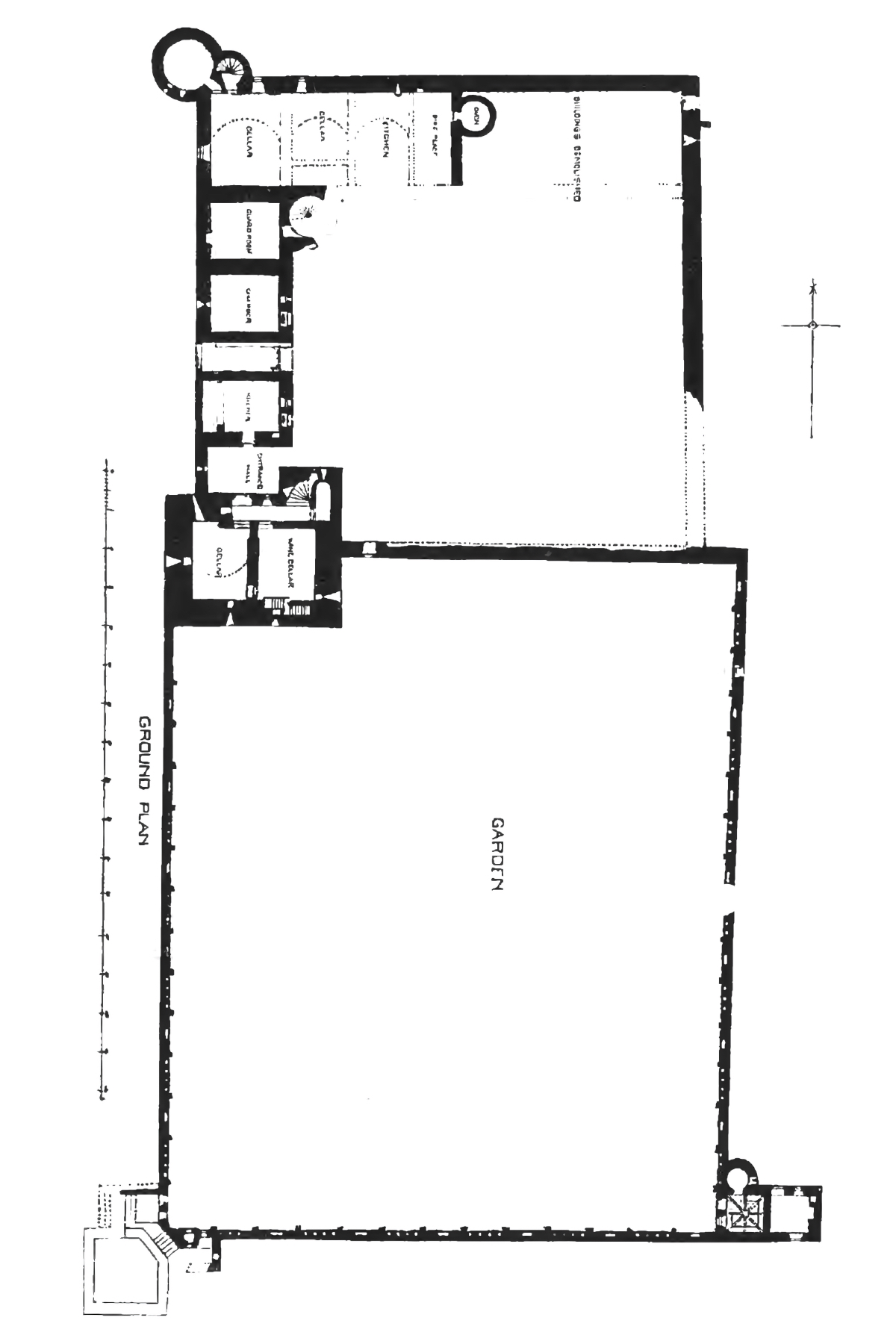

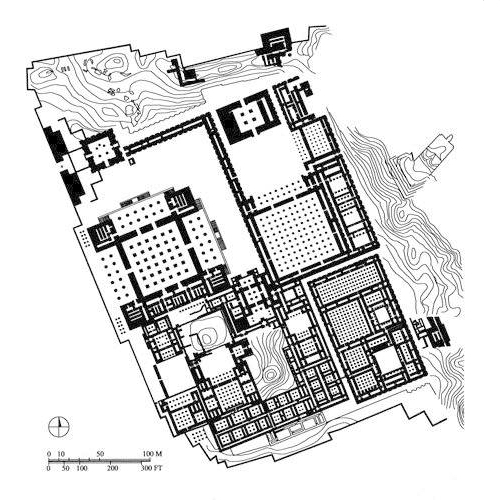

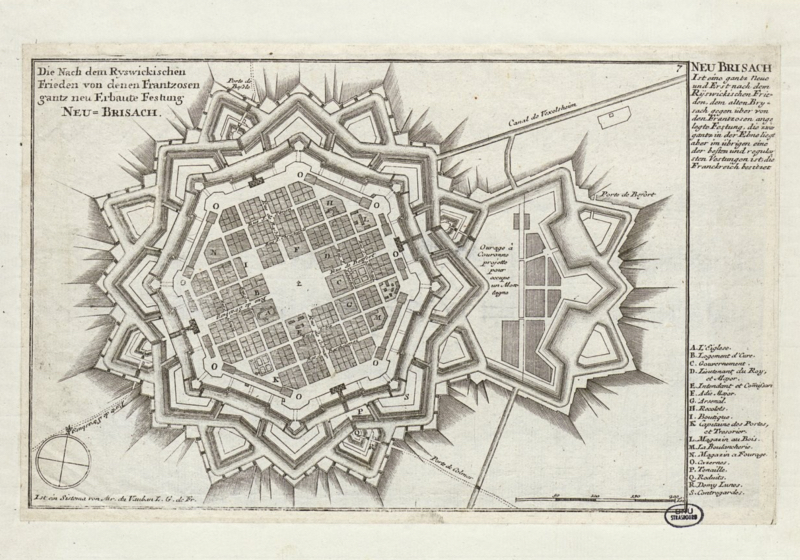

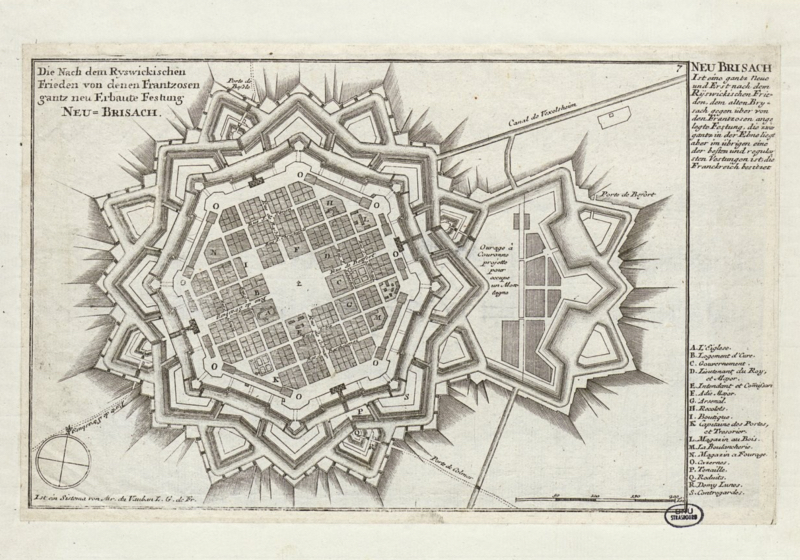

Site Plan of Neuf Brisach

from Gabriel Bodenehr: Die Nach dem Ryswickischen Frieden von denen Frantzosen gantz neu Erbaute Festung Neu-Brisach c. 1697.

from Gabriel Bodenehr: Die Nach dem Ryswickischen Frieden von denen Frantzosen gantz neu Erbaute Festung Neu-Brisach c. 1697.

Neuf Brisach: The Art of War

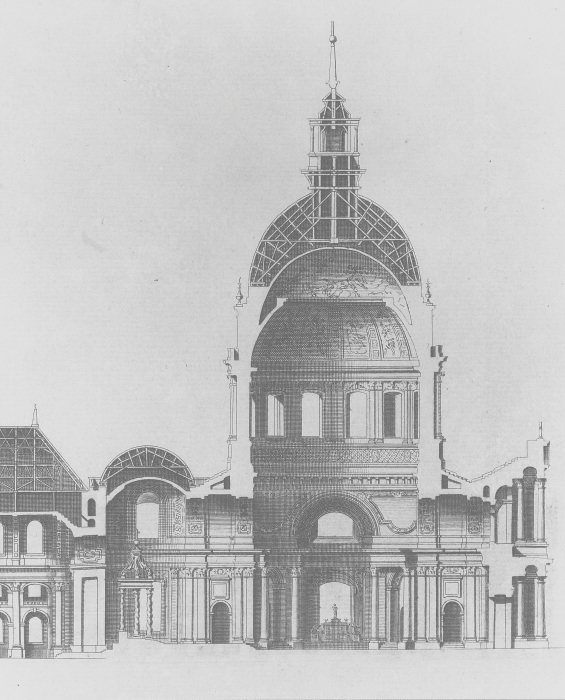

Can we appreciate the work of the military engineer Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban as art? Is there a point at which we can see that this mixture of landscape and architecture transcends its utility as military engineering and becomes an object of aesthetic speculation? Could Vauban himself have regarded his work, at the point when the engineering requirements had been satisfied, as being art? Vincent Scully suggests as much:

Le Nôtre's étoiles at Versailles were matched by Vauban's étoiles along the Rhone... Vauban built his forts in echelon, in depth behind the frontier everywhere; they were reflections of the same art that shaped the gardens, projecting as they did long lines of flat-trajectory cannon fire to the horizon. As such, their outerworks, their dehors, kept expanding too. It always seemed advisable to have another demi-line, ravelin, and glacis out there in space. [1]

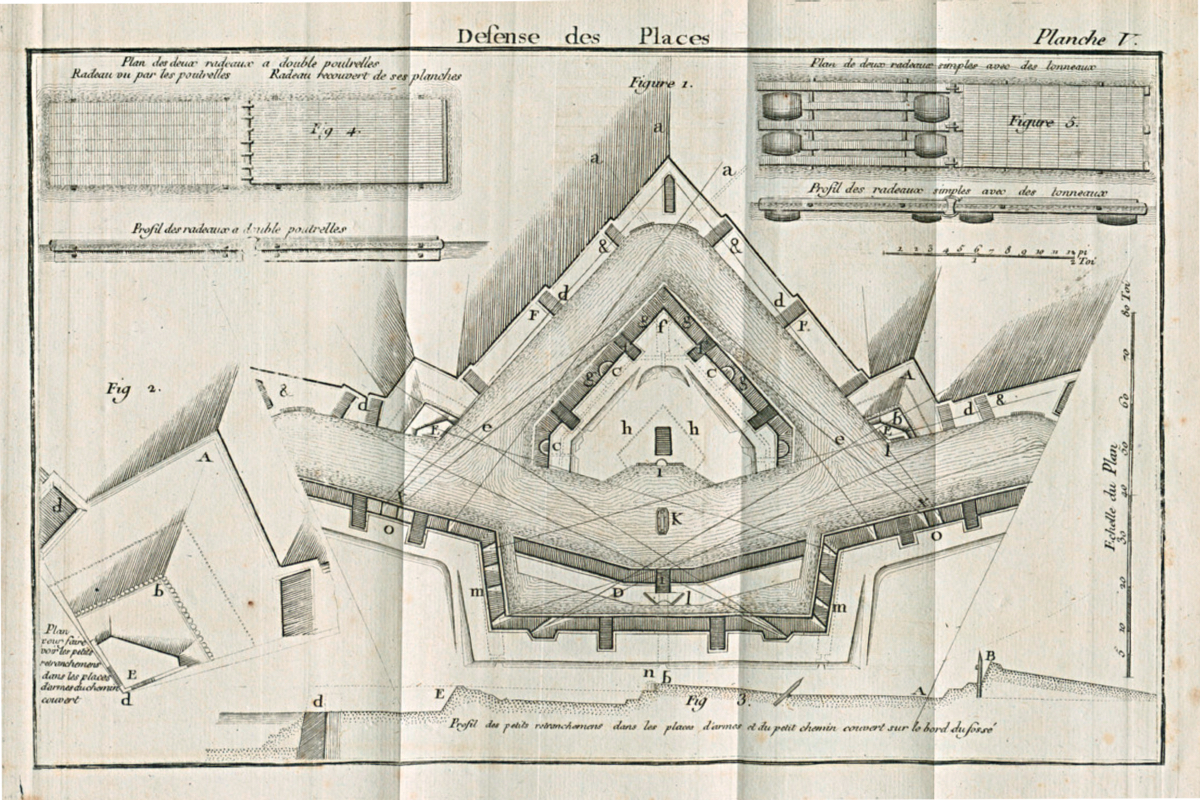

Vauban: Traité de la défense des places (Paris 1769)

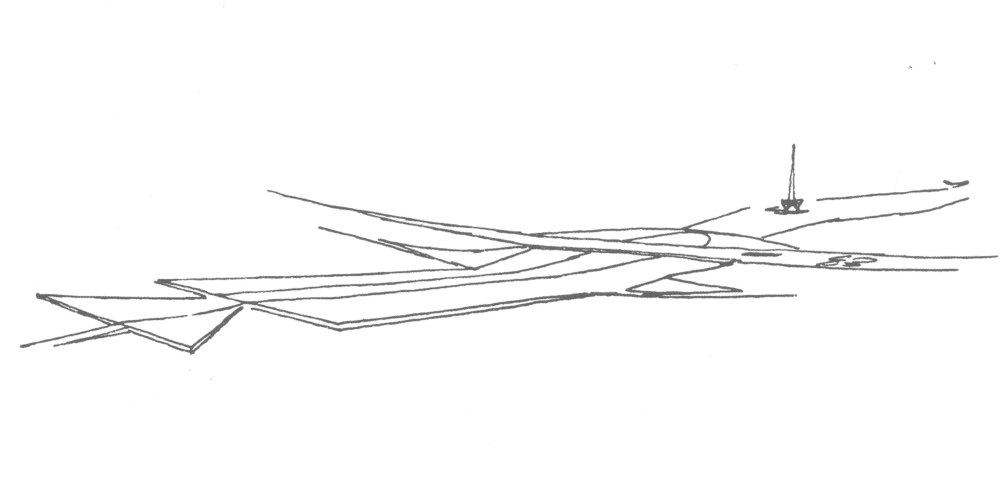

roll over for illustration of sweeps of space

The sweeps of space equal the sweeps of gunfire, firing along, rather than away from, the walls. The outerworks protected the walls from direct attack and channelled the enemy into the dry moats.

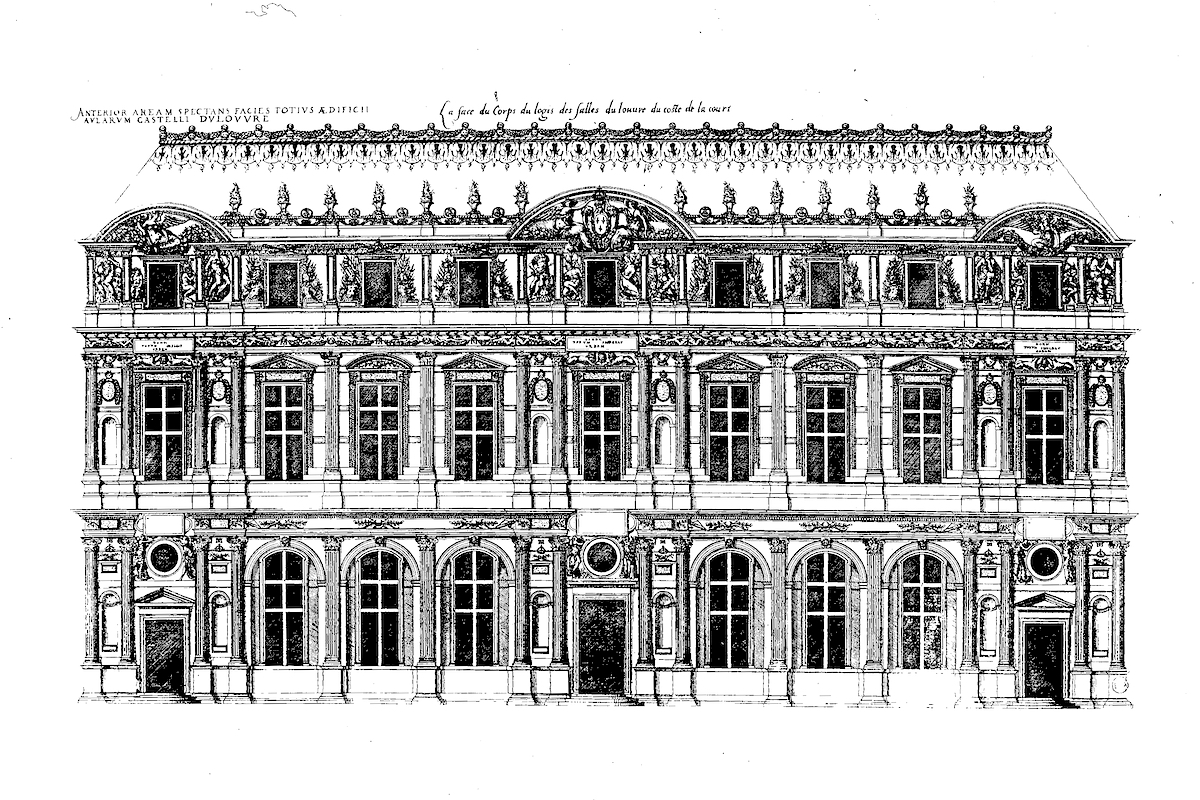

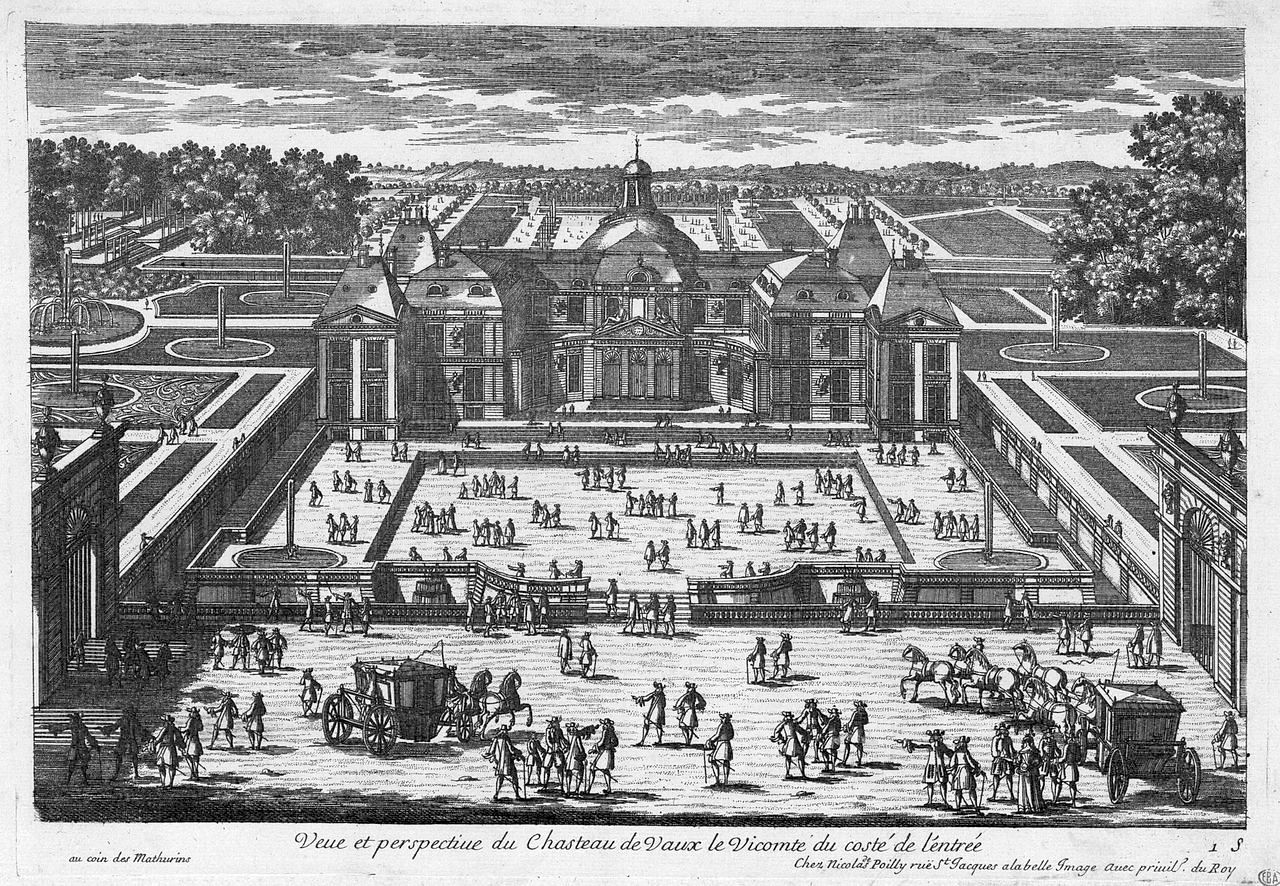

It's unlikely that Vauban considered his work as aesthetic in any sense. The concept of sweeps of space was undoubtedly linked, however, to the work of the architects Louis Le Vaux and André Le Nôtre at Vaux-le-Vicomte. Theirs was an reinterpretation of the sweeps of celestial space of Kepler's Three Laws of Planetary Motion as sweeps of terrestrial space, as I describe in my article Vaux-le-Vicomte: Architecture and Astronomy.

Vauban: Neuf Brisach c. 1697

© Thomas Deckker 2022

© Thomas Deckker 2022

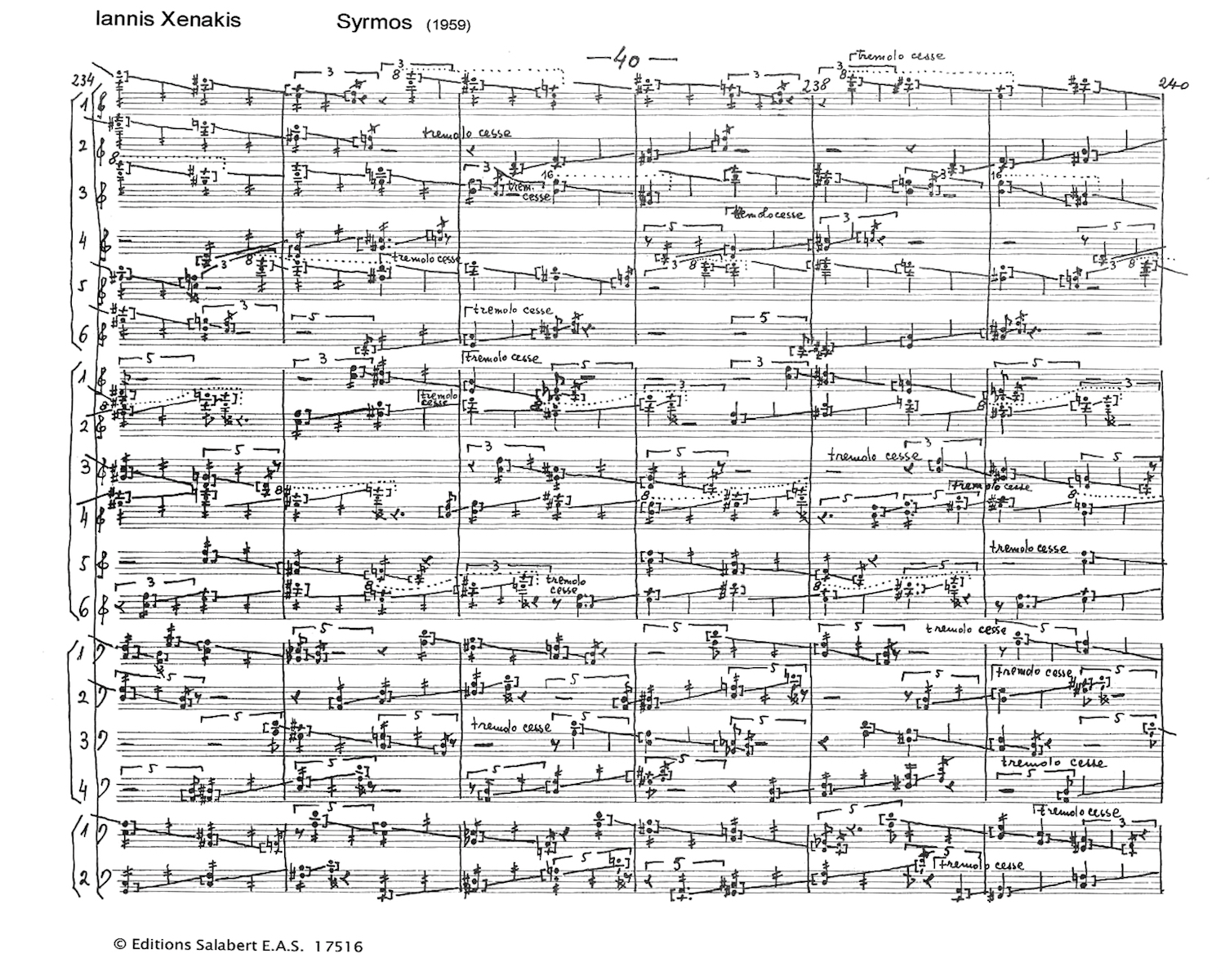

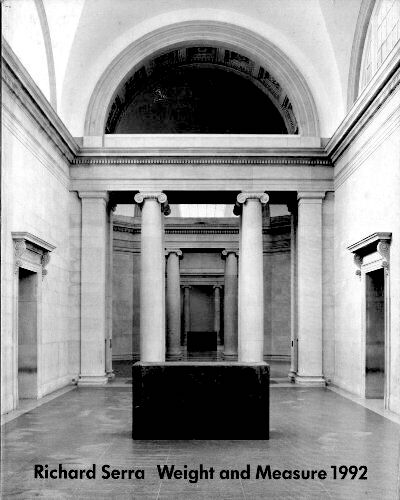

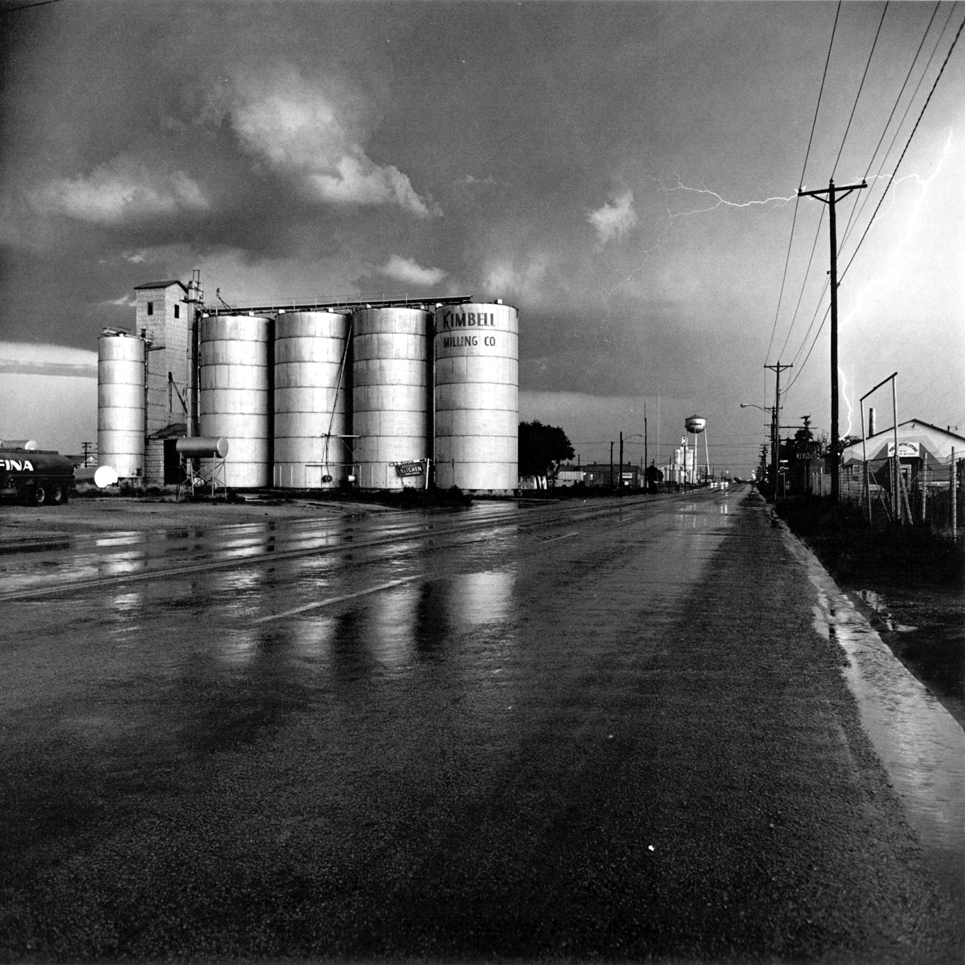

Some of my favourite artists use architectural ideas to structure landscape: Richard Serra and Donald Judd, and especially Maya Lin: her Wave Field consists of shapes in the landscape generated by a "naturally occurring repetitive water wave". It is an approach to understanding architecture and landscape that I used fruitfully at the University of East London, Universität Liechtenstein and, most recently, at the University of Dundee, where I ran my Year 4 Design Research Unit: Landscape:Architecture. The reinterpretation of objects not originally conceived as art, such as grain elevators, has acknowledged the - intended or not - aesthetics of engineering. The composer, engineer and architect Iannis Xenakis was captivated by the stochastic trajectories of gunfire during the Second World War.

The development of baroque architecture is often seen as a matter of style or connoisseurship, and dismissed as decorative. Baroque domestic and military architecture was developed by architectural theoreticians and practitioners who not only were familiar with contemporary treatises in mathematics and astronomy but were aware of their practical applications. The shift from renaissance to baroque was fundamentally a shift in knowledge. This is a theme I developed in two articles on Architecture and Astronomy: Vaux-le-Vicomte and The Temple of Apollo at Stourhead.

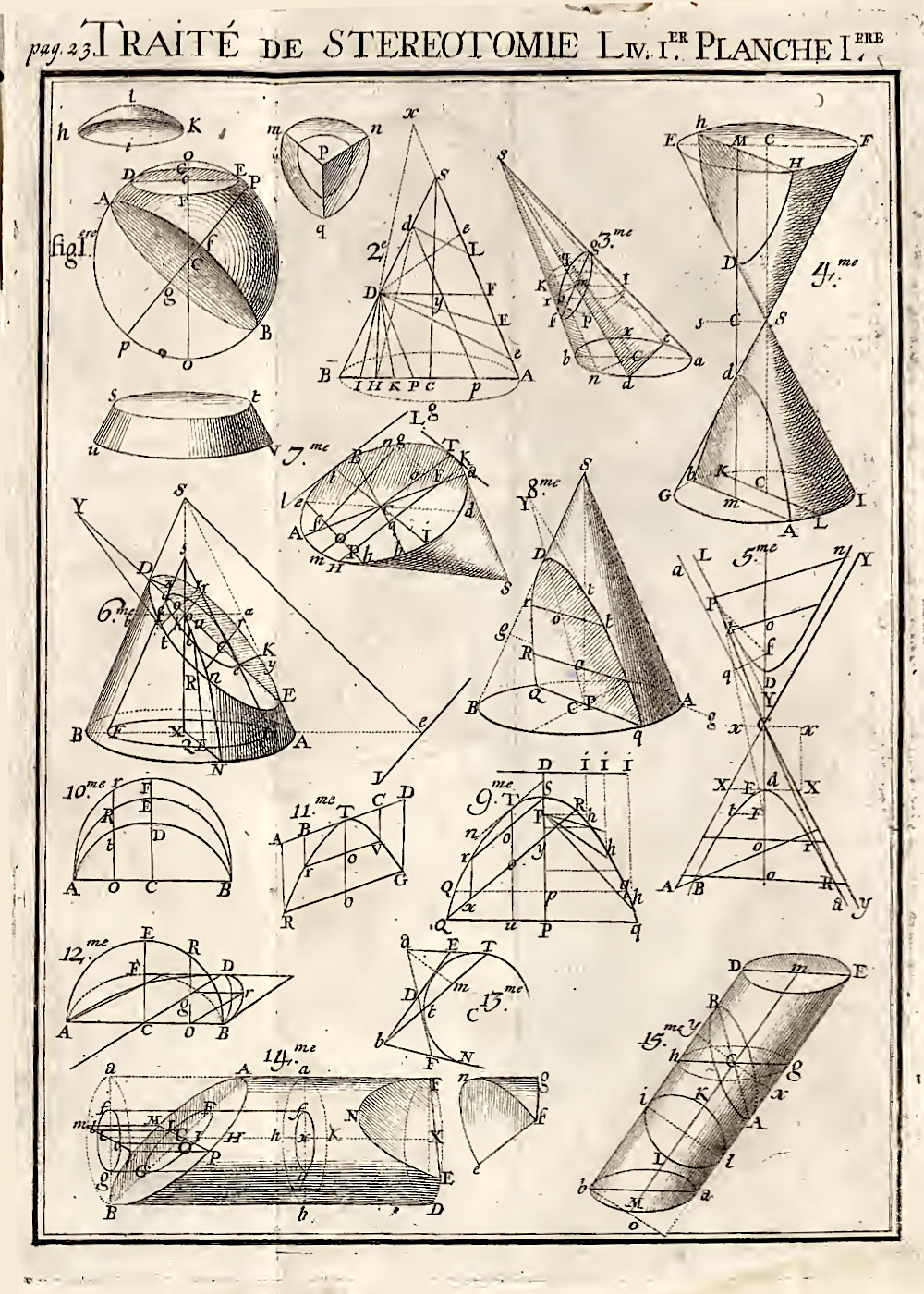

In the mid-sixteenth century in France a number of factors, interconnected and acting simultaneously, formed an epistemological break or paradigmatic shift in the understanding of space, whether geometrical, astronomical, architectural or topographical: first, the conceptual leap in astronomy of space as infinite with planets in elliptical orbits around the sun, by the German astronomer Johannes Kepler; second, the rediscovery of conic sections - ellipses, parabolas and hyperbolas - in mathematics, in projective and descriptive geometry, by the French mathematician and architect Girard Desargues; third, the practical application of projective and descriptive geometry in architecture and landscape, both in design and construction, by architects such as Louis Le Vaux and André Le Nôtre, and fourth, the application of projective geometry as both a symbolic representation and practical embodiment of the French State in the person of Louis XIV, the Sun-King. Some at least of these factors applied to England, as described by Stephen Johnston and Anthony Gerbino in Compass and Rule: Architecture as Mathematical Practice in England 1500-1750.

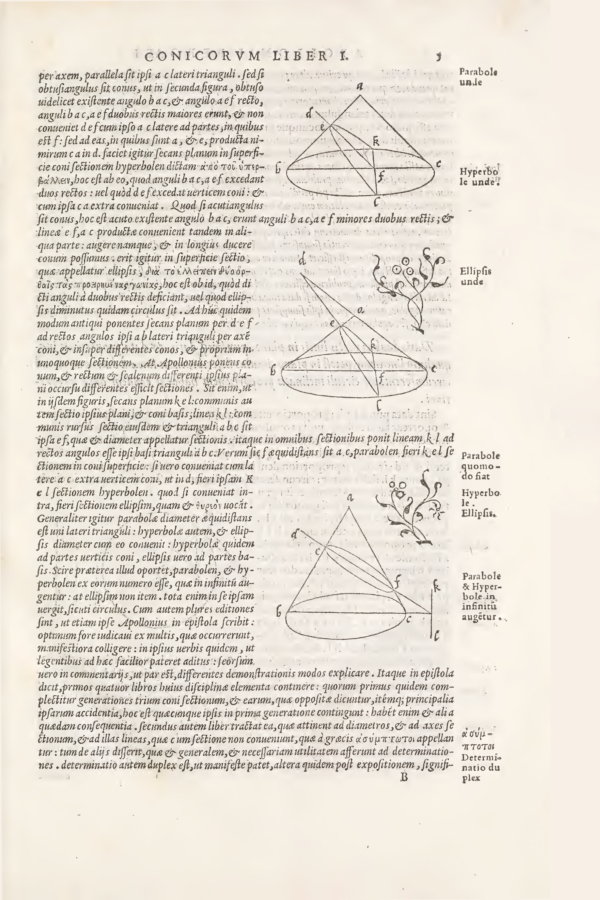

parabola, hyperbola and ellipse

from Federico Commandino's translation of Conics by Apollonius of Perga (Venice 1566)

from Federico Commandino's translation of Conics by Apollonius of Perga (Venice 1566)

Conics by Apollonius of Perga (c. 240 BC - c. 190 BC) is one of the great scientific works of Greek Antiquity. It survived in fragments and translations; its rediscovery during the Renaissance underlay much scientific thought of that period and later.

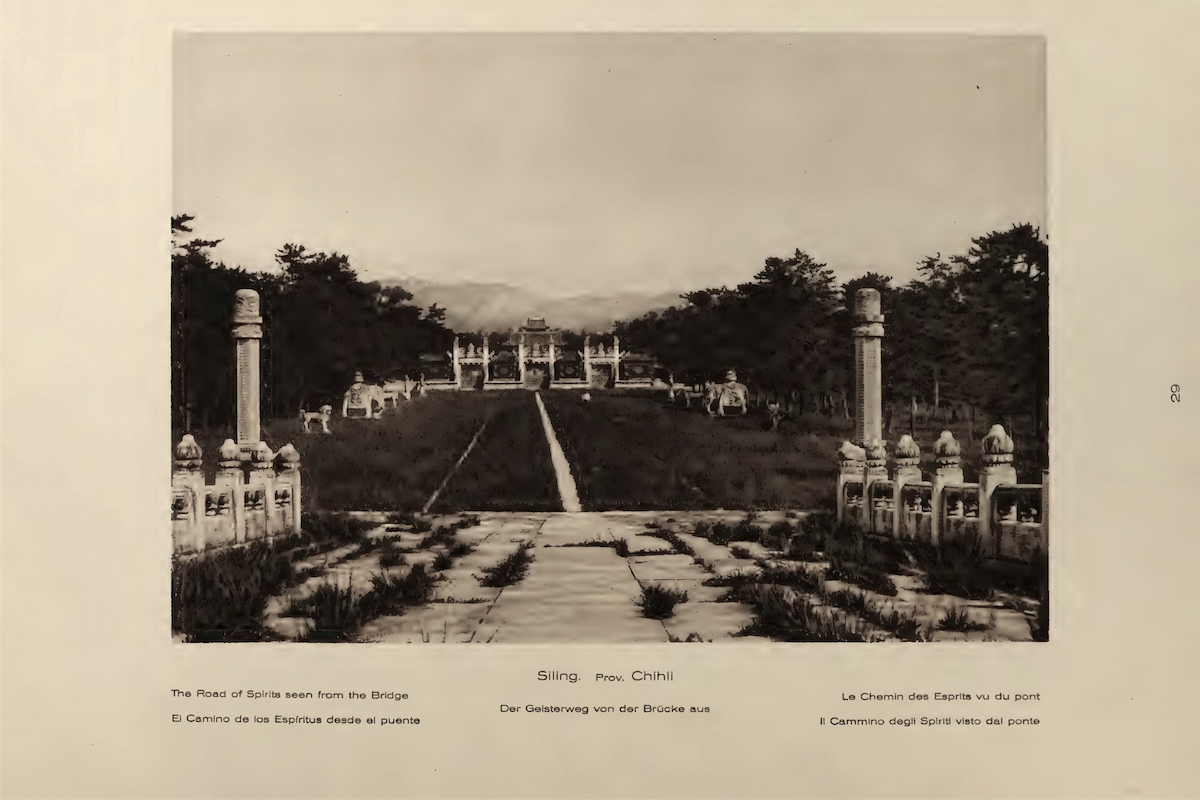

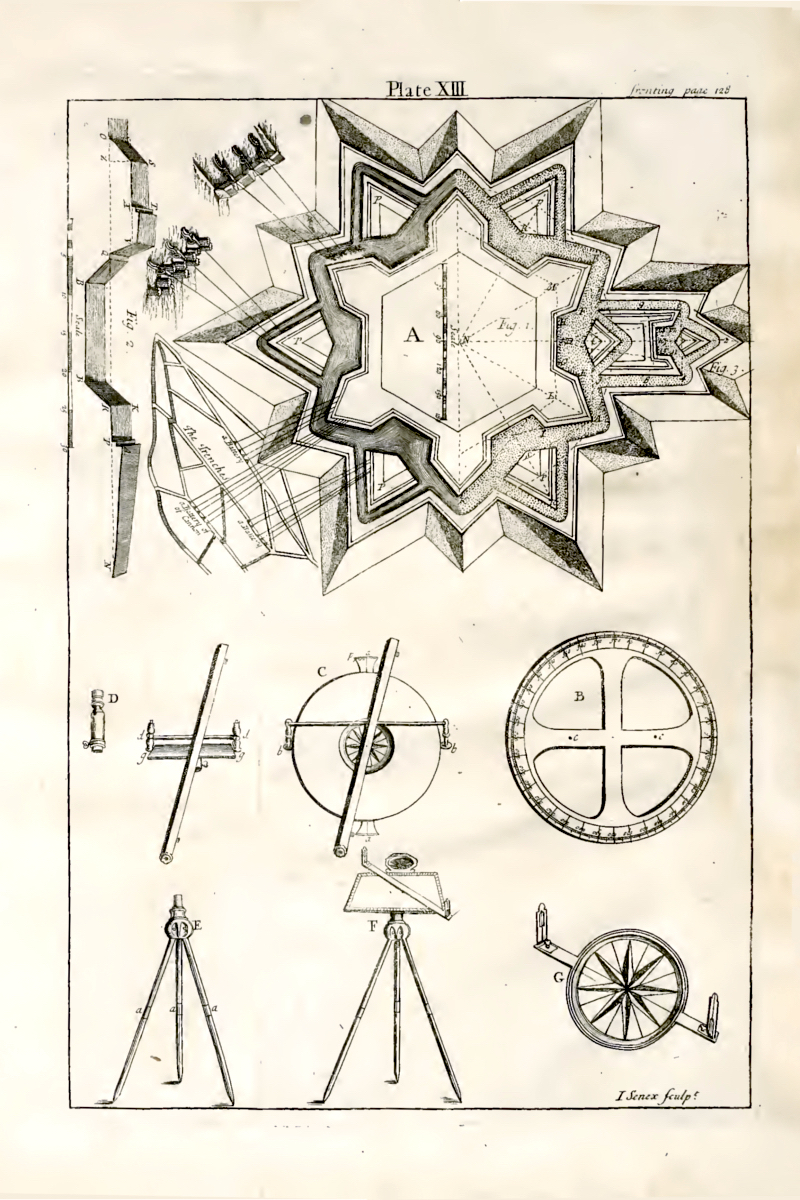

The mathematics of conic sections supported a new science of optics. Among the new optical tools were the theodolite and level, made more accurate by the use of the telescope for sighting long distances and microscope for reading vernier scales. The astronomer Jean Picard of the Académie Royale des Sciences, famous at the time for accurately measuring the diameter of the Earth, made a telescopic level for setting out the gardens at Versailles, necessary because of the large basins of water and poor water supply. The sector or military compass could be used used both for surveying and gunnery; Galileo is credited as one of its inventors, published in Le Operazione del compasso geometrico e militare in 1606. The architect Pierre Bullet made a plane table, called a pantomètre, for his pioneering map of Paris; he published Traité de l'usage du pantomètre in 1675, and Traité du nivellement in 1688 as well as Architecture pratique in 1691. Of course, the instruments used for surveying (reproducing the landscape on a small scale on paper) could also be used for setting out designs from drawings at a large scale onto the landscape. We know that Vauban used these surveying techniques because scale models of his fortifications (and many others) are exhibited in the Musée des Plans-Reliefs in Paris, founded for him in 1668.

Plate XIII

Edmund Stone: The Construction and Principal Uses of Mathematical Instruments (London 1728)

Edmund Stone: The Construction and Principal Uses of Mathematical Instruments (London 1728)

This book, a translation into English of the Traité de la construction et des principaux usages des instrumens de mathématique (1709) by Nicholas Bion, shows the use of plane tables and levels to survey a fort similar to Neuf Brisach.

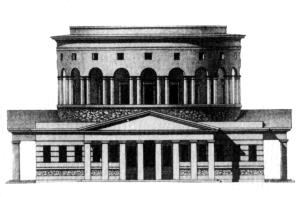

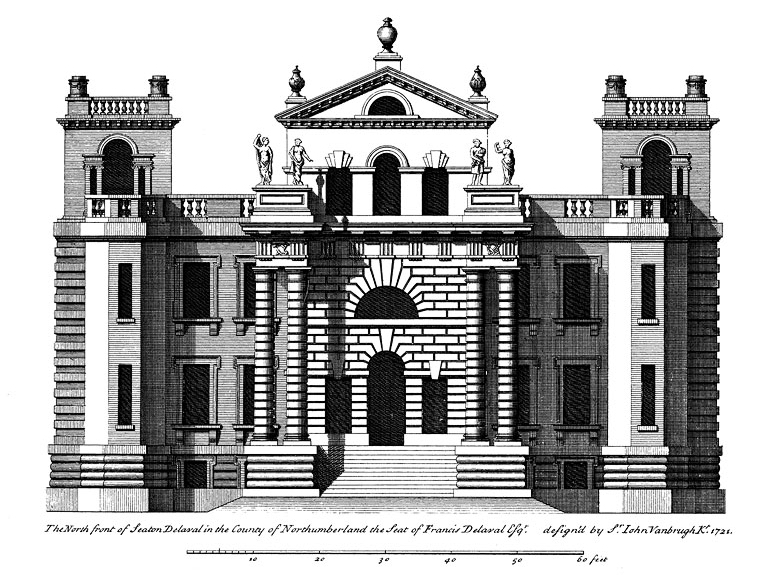

Military architecture in Europe developed from Italian Renaissance models; bastions had been developed by Giuliano da Sangallo at Poggio Imperiale in 1487 and Antonio da Sangallo the Elder at Civita Castellana in 1494. Antonio da Sangallo the Younger used bastions at an urban scale for the walls of Rome in 1534; by the end of the century a coherent system of fortification called trace italienne had developed. The French soon had their own treatises, such as Jacques Perret: Architectura et perspectiva: des fortifications & artifices [Architecture and Perspective: Fortifications and Fireworks] published in 1601, and Bernard Forest de Belidor. Baroque military engineering did not overturn these designs: it extended them into the landscape.

Vauban: Traité de la défense des places

Vauban: A Treatise on Defence

Published posthumously in Paris in 1769.

Vauban: A Treatise on Defence

Published posthumously in Paris in 1769.

Bernard Forest de Belidor: Le Bombardier françois, ou Nouvelle méthode de jetter les bombes avec précision

Bernard Forest de Belidor: The French Gunner, or a new method for firing bombs with precision

Roll over for an illustration of a siege. The new mathematics of conic sections (such as parabolas) allowed the trajectory of shells to be calculated accurately.

Bernard Forest de Belidor: The French Gunner, or a new method for firing bombs with precision

Roll over for an illustration of a siege. The new mathematics of conic sections (such as parabolas) allowed the trajectory of shells to be calculated accurately.

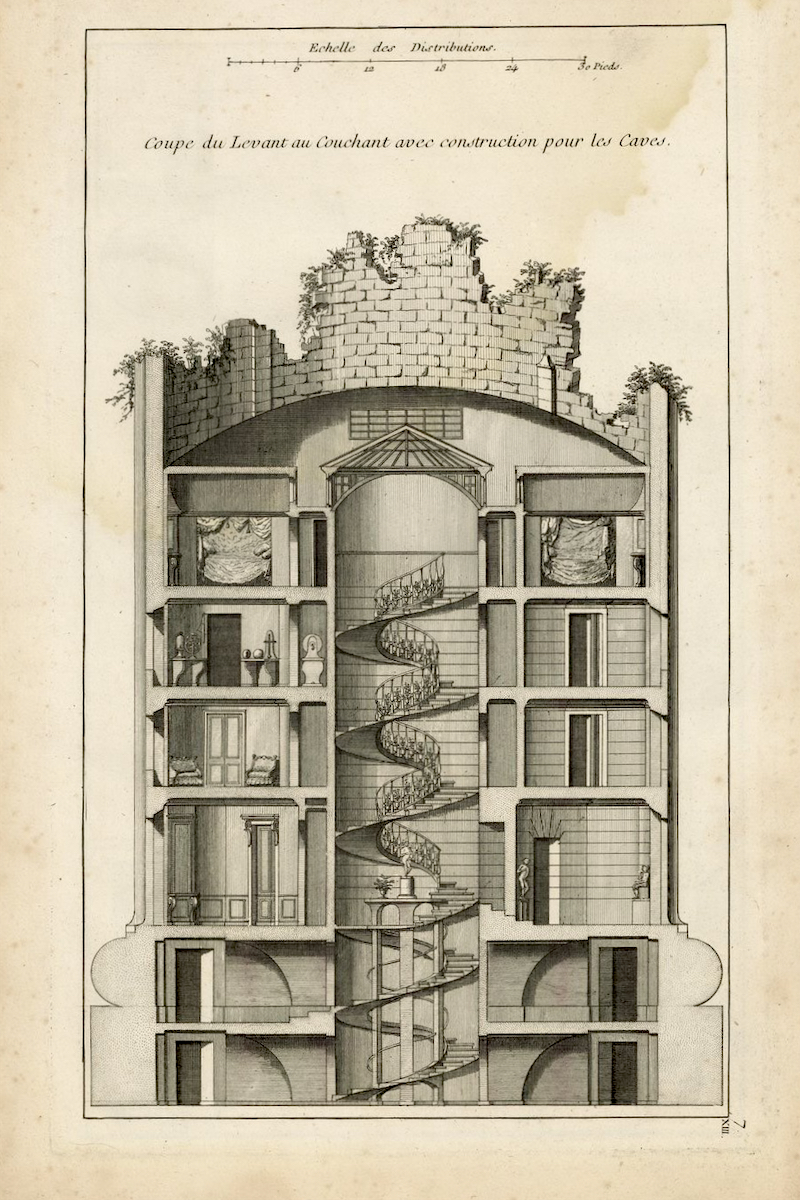

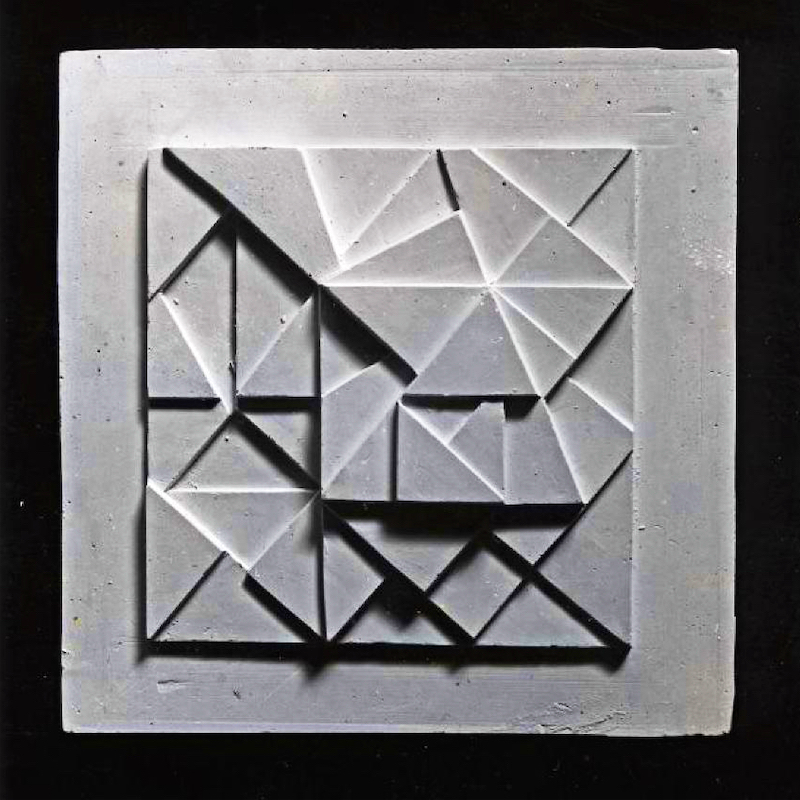

Conic sections and projective geometry had a practical as well as a conceptual application in architecture. The fabulous precision and inventiveness of French stéréotomie - the geometry of stone cutting - was available for all to see not only in medieval churches, where it was the preserve of maçons [masons], but in renaissance domestic architecture: spiral staircases often appeared as chef d'oeuvres, such as the double spiral at the Château de Chambord (1519-), the tower at the Château de Blois (1515-19), and in innumerable lesser ones. The application of stéréotomie for architects was the design of complex shapes, but it had a practical purpose for masons: stone needed to be cut swiftly and accurately in yards on the ground and then hoisted into position on the work site. This could mean, in domestic architecture, the intersection of a window - trapezoidal in plan and with a vaulted head - in an oval room, and in military architecture an embrasure - trapezoidal in plan, perhaps falling to the exterior in section and with a vaulted head - in an irregular bastion, and in fact just this type of design problem appeared in Frézier's La Théorie et la Pratique de la Coupe des Pierres [The Theory and Practice of Stone Cutting] of 1737.

Amédée-François Frézier: La Théorie et la Pratique de la Coupe des Pierres (Strasbourg and Paris 1737) Plate 36

The geometry of stone cutting may seen in Frézier's illustration of a bastion such as those at Neuf Brisach. Descriptive geometry, which encompasses stereotomy, was developed into a science by Gaspar Monge, one of the founders of the École Polytechnique, in Paris in the 18th century.

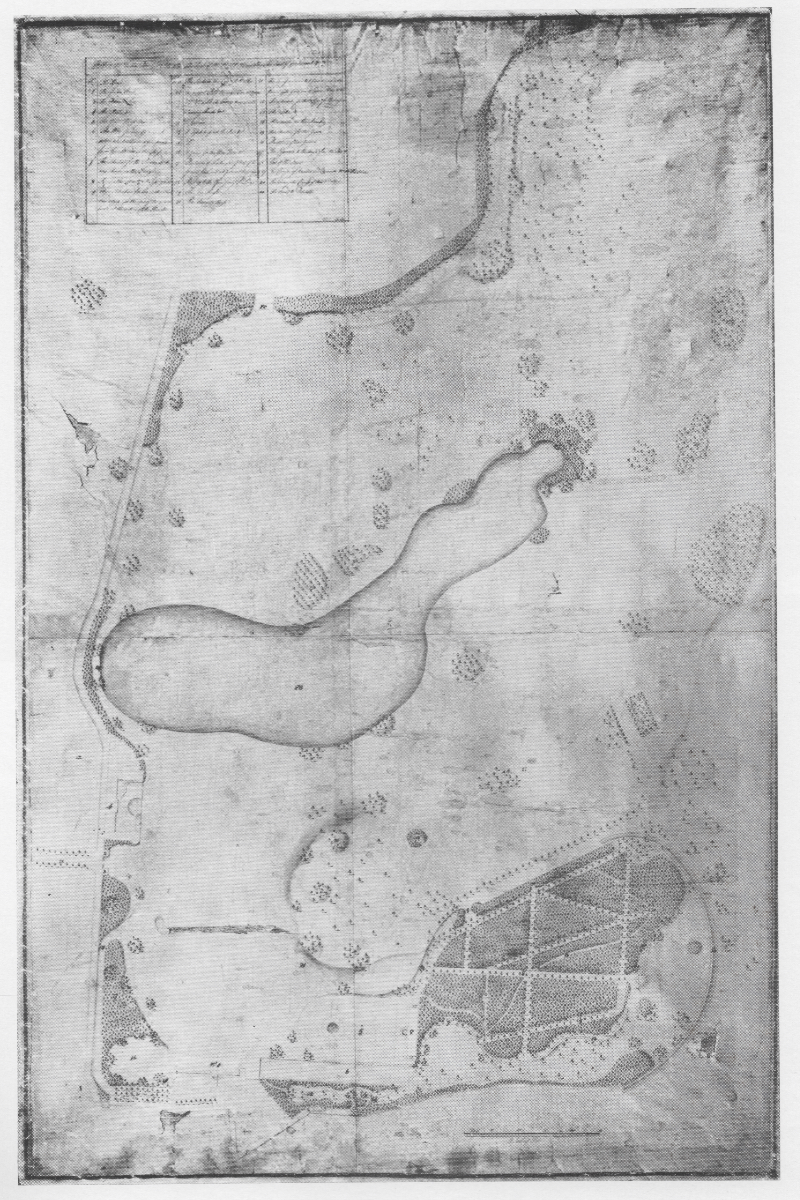

Vauban: Neuf Brisach c. 1697

© Thomas Deckker 2022

© Thomas Deckker 2022

Footnotes

1. 'Architecture: The Natural and the Manmade' in Stuart Wrede and William Howard Adams (eds): Denatured Visions New York: The Museum of Modern Art 1991) ↩

Thomas Deckker

London 2022

London 2022