thomas

deckker

architect

critical reflections

John Onians: ‘Architecture, Metaphor and the Mind’

2021

2021

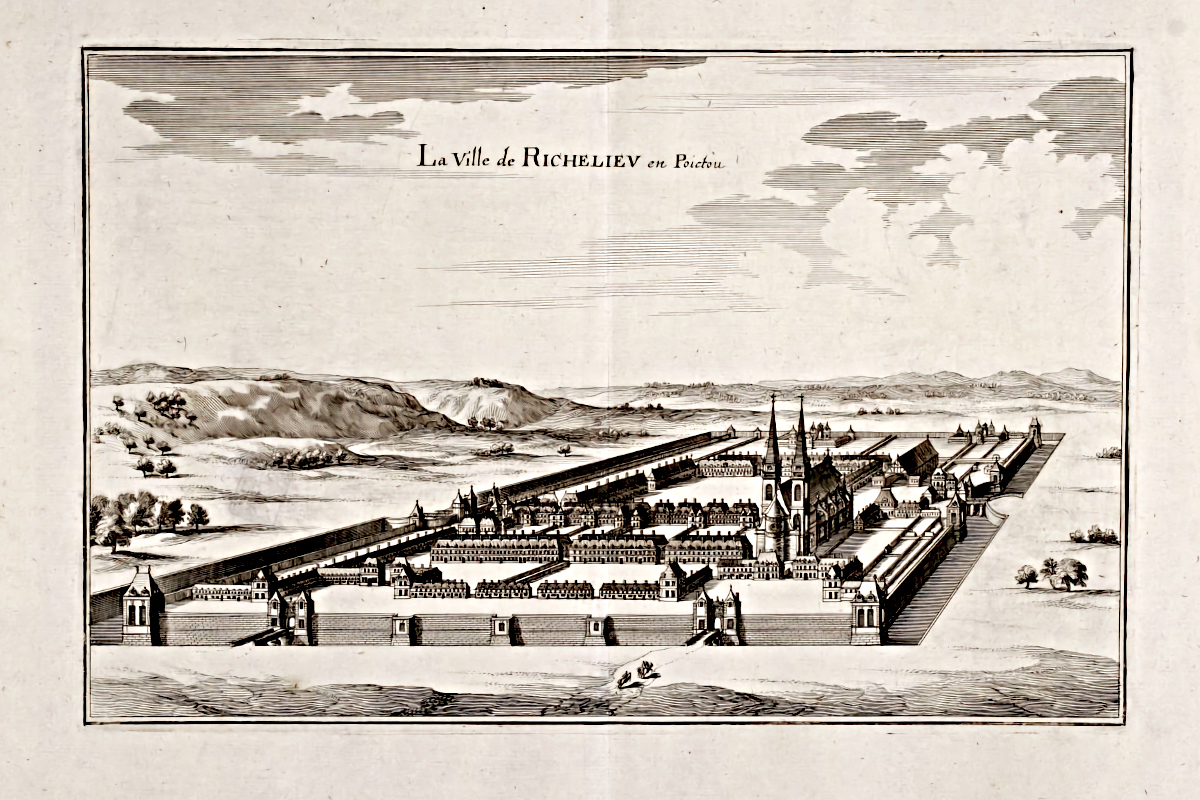

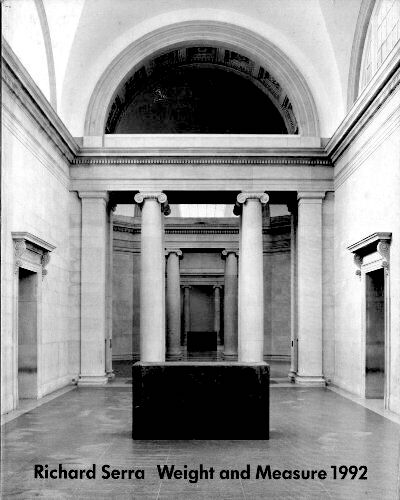

Marc-Antoine Laugier: Essai sur l'Architecture

Paris, 1755

Paris, 1755

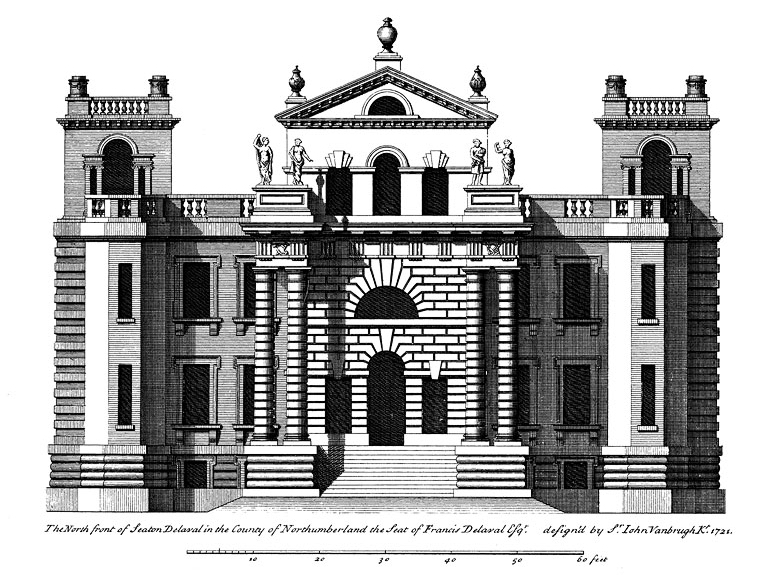

The 'primitive hut', or the origins of architecture, interpreted by Marc-Antoine Laugier.

John Onians: ‘Architecture, Metaphor and the Mind’

John Onians's paper ‘Architecture, Metaphor and the Mind’ contains, I believe, the key to understanding the relationship of architecture to everyday life:

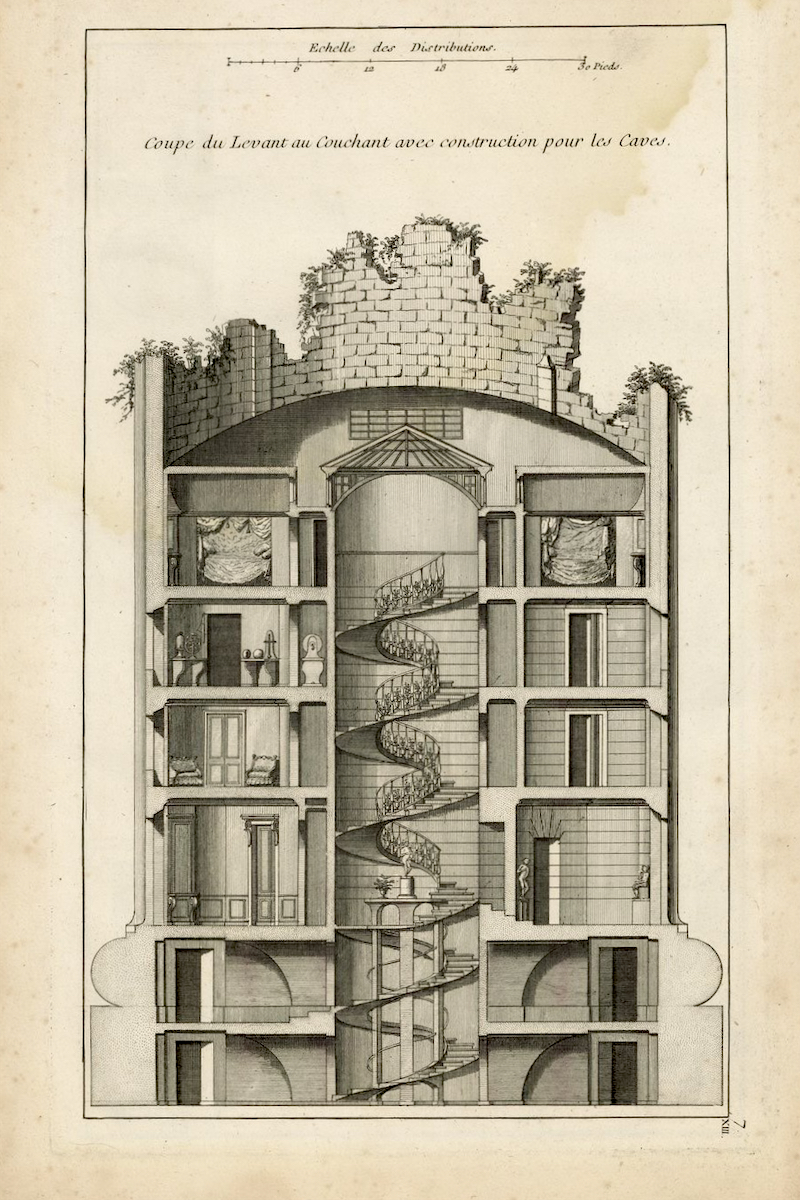

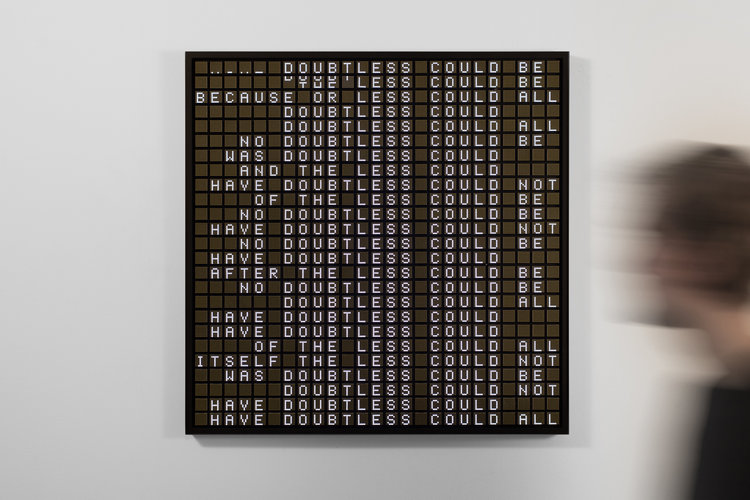

What is argued is that the making of buildings and the experiencing of buildings are both associated with distinctive mental operations and that this association is apparent in our use of language. To put it another way, we use metaphors from architecture to articulate our thoughts because the processes of design and construction and the experience of using building relate to basic mental operations and basic psychological needs. In other words, when we derive from building design the metaphor 'plan', as in 'five-year plan', or from building construction the expression 'foundations', as in 'foundations of economic theory' or from the experience of a building once constructed the concept of 'pillars', as in 'pillars of society', we do so because there is a uniquely close relationship between building and thinking.

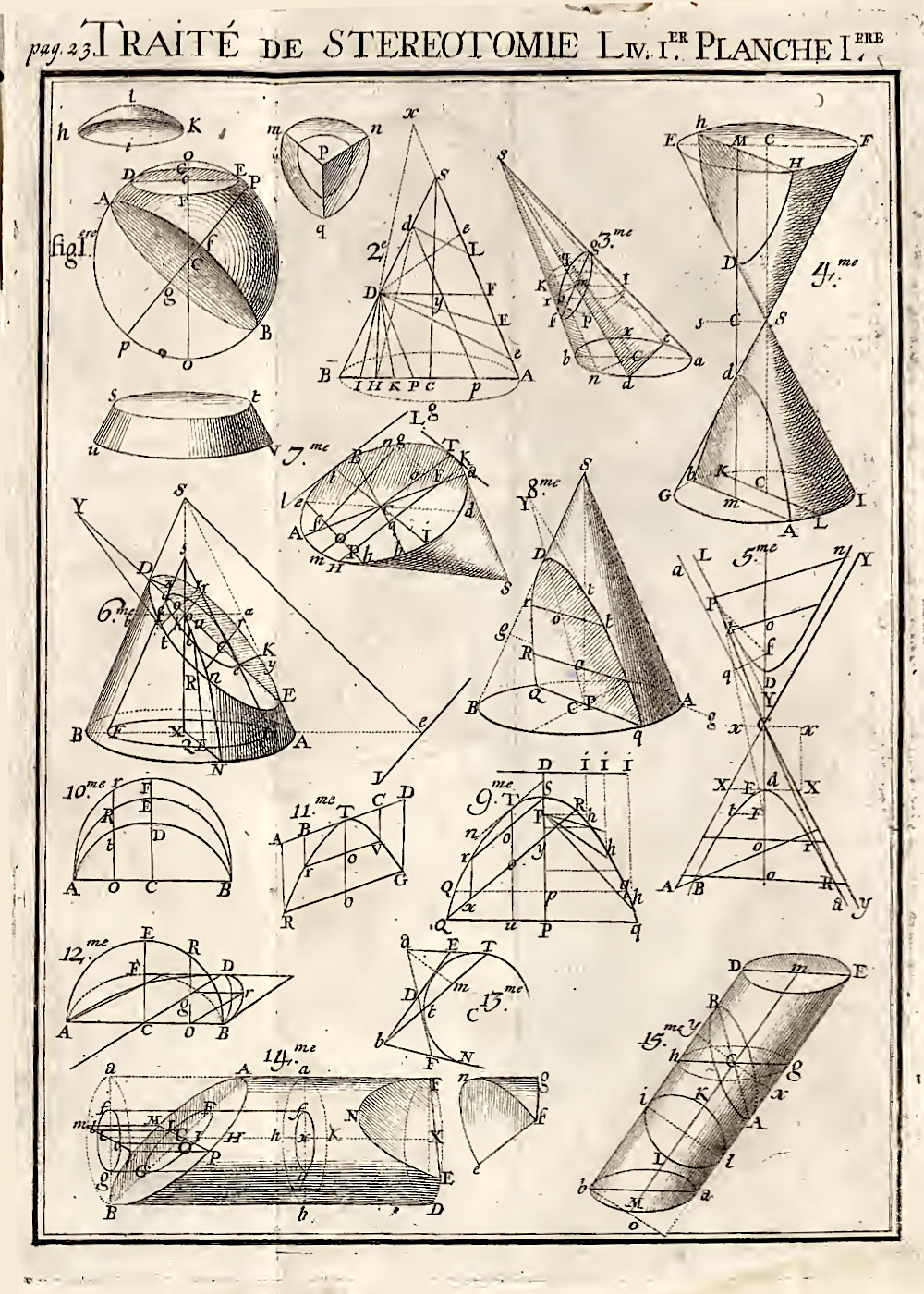

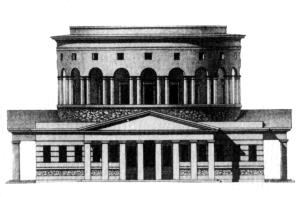

The idea coud not be put more clearly: we conceptualise abstract mental operations as metaphors for physical buildings. Thus disciplines in the humanities often use words and concepts derived from architecture, as I described in my article Architecture and the Humanities. What gives this theory even greater credibility than the hieroglyphic and alphabetic evidence Onians presents is his observation that many words in architecture are derived from descriptions of the human body, up to and including the word Vitruvius uses for plan, the Greek word ichnographia, or footprint. I like to think that the idea of architecture representing the human body ended with Ledoux and the barrières, overtaken by the rationalism of Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand, whose Précis des leçons d'architecture données à l'École polytechnique was published in 1802.

In case there was any doubt about whether architecture was fundamental, or just a convenient correspondence, to the birth of Western civilisation, Onians goes on to say:

In case there was any doubt about whether architecture was fundamental, or just a convenient correspondence, to the birth of Western civilisation, Onians goes on to say:

Since Greek architecture developed before Greek thought it can be argued that it was their experience of architecture which taught the Greeks how to think. It was by analogy with buildings that the Greeks developed the idea of knowledge and of language as phenomena possessing structural properties.

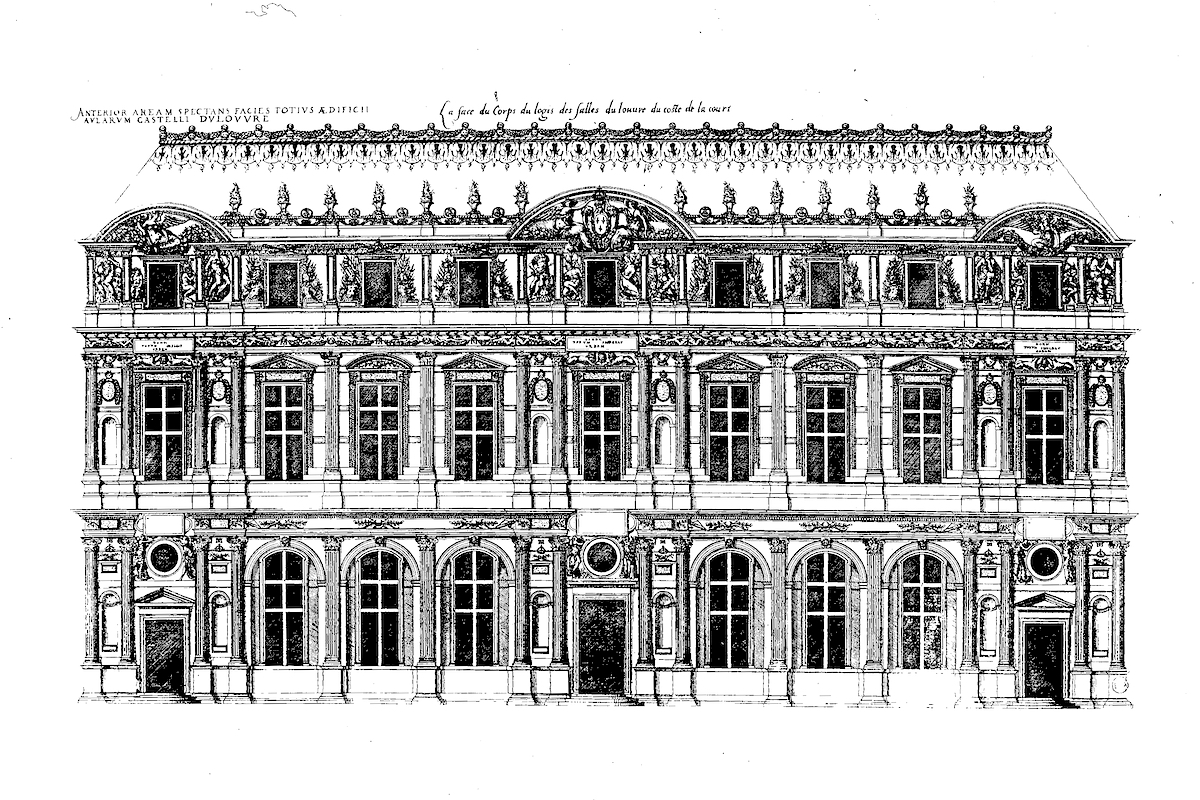

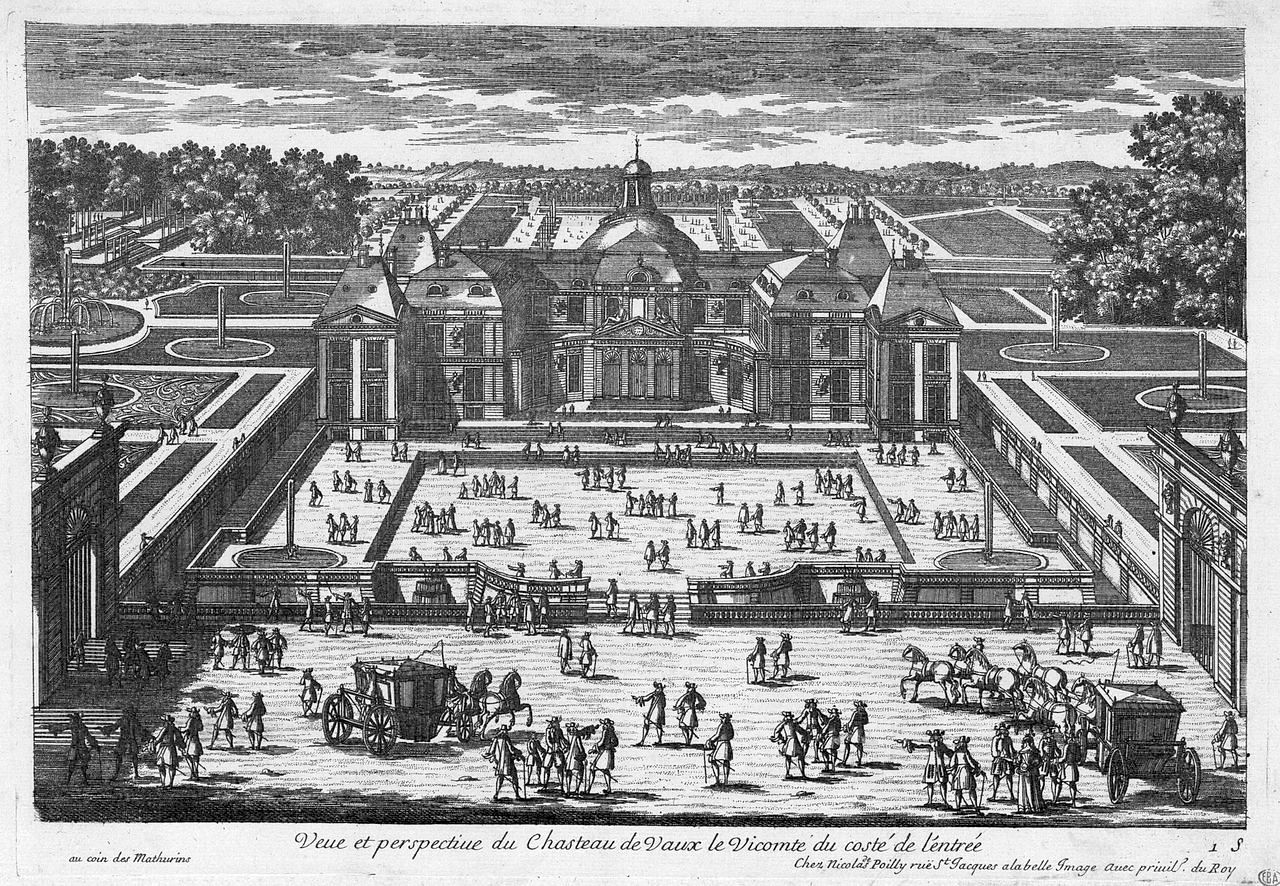

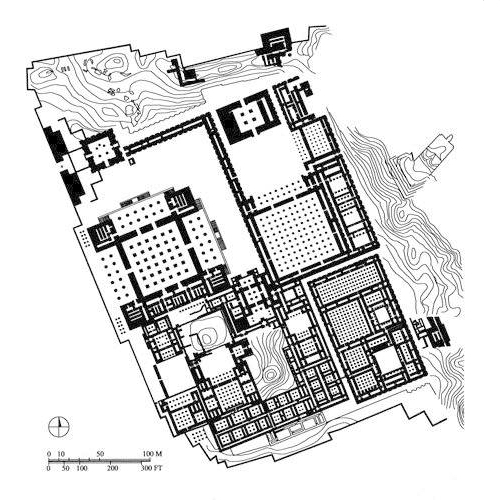

The engraving, by Jacques Aliamet of a drawing by Charles-Dominique-Joseph Eisen, is the frontispiece to Marc-Antoine Laugier's Essai sur l'Architecture, an 18th century interpretation of the origin of architecture put forward by Vitruvius:

Thus the discovery of fire gave rise to the first assembly of mankind, to their first deliberations, and to their union in a state of society. For association with each other they were more fitted by nature than other animals, from their erect posture, which also gave them the advantage of continually viewing the stars and firmament, no less than from their being able to grasp and lift an object, and turn it about with their hands and fingers. In the assembly, therefore, which thus brought them first together, they were led to the consideration of sheltering themselves from the seasons, some by making arbours with the boughs of trees, some by excavating caves in the mountains, and others in imitation of the nests and habitations of swallows, by making dwellings of twigs interwoven and covered with mud or clay. From observation of and improvement on each others' expedients for sheltering themselves, they soon began to provide a better species of huts. [1]

Laugier put forward the thesis that the 'primitive hut' was transformed, through mimesis, from the Ancient Greek μίμησις, into the Greek temple. It is extraordinary to think that the 'distinctive mental operations' of Greek thought developed from 'observation of and improvement on each others' expedients' of huts, but 'this association is apparent in our use of language'.

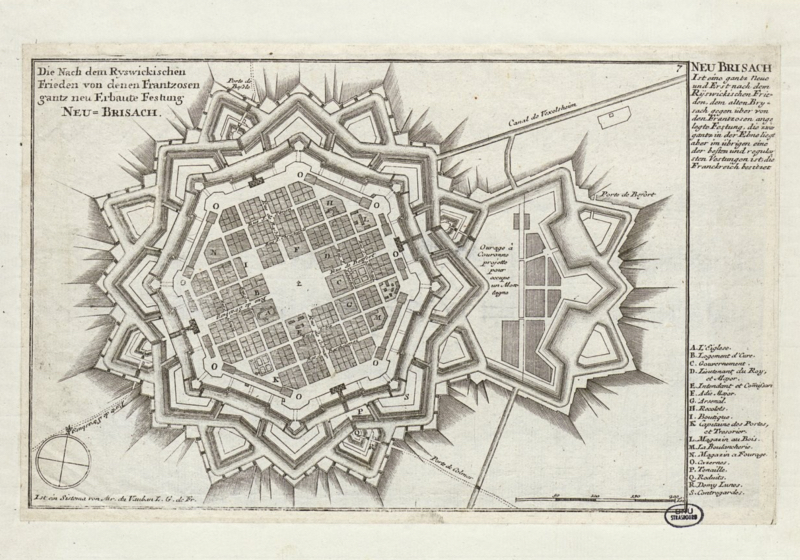

In my article Architecture and the Humanities I speculated on why disciplines in the humanities used words and concepts derived from architecture but ignored the discipline of architecture itself. It's certainly possible that architecture has abandoned its connection to language and pursued, at best, a technological and pragmatic rationale exemplified by Durand's Précis.

Available on JSTOR: John Onians: ‘Architecture, Metaphor and the Mind’ Architectural History 35 (1992) pp. 192-207

In my article Architecture and the Humanities I speculated on why disciplines in the humanities used words and concepts derived from architecture but ignored the discipline of architecture itself. It's certainly possible that architecture has abandoned its connection to language and pursued, at best, a technological and pragmatic rationale exemplified by Durand's Précis.

Available on JSTOR: John Onians: ‘Architecture, Metaphor and the Mind’ Architectural History 35 (1992) pp. 192-207

Thomas Deckker

London 2021

London 2021

Footnotes

1. II - 1 - 2. Vitruvius: The Ten Books on Architecture (transl. Morris Hicky Morgan; Cambridge: Harvard University Press; London: Humphrey Milford; Oxford University Press; 1914) ↩