thomas

deckker

architect

critical reflections

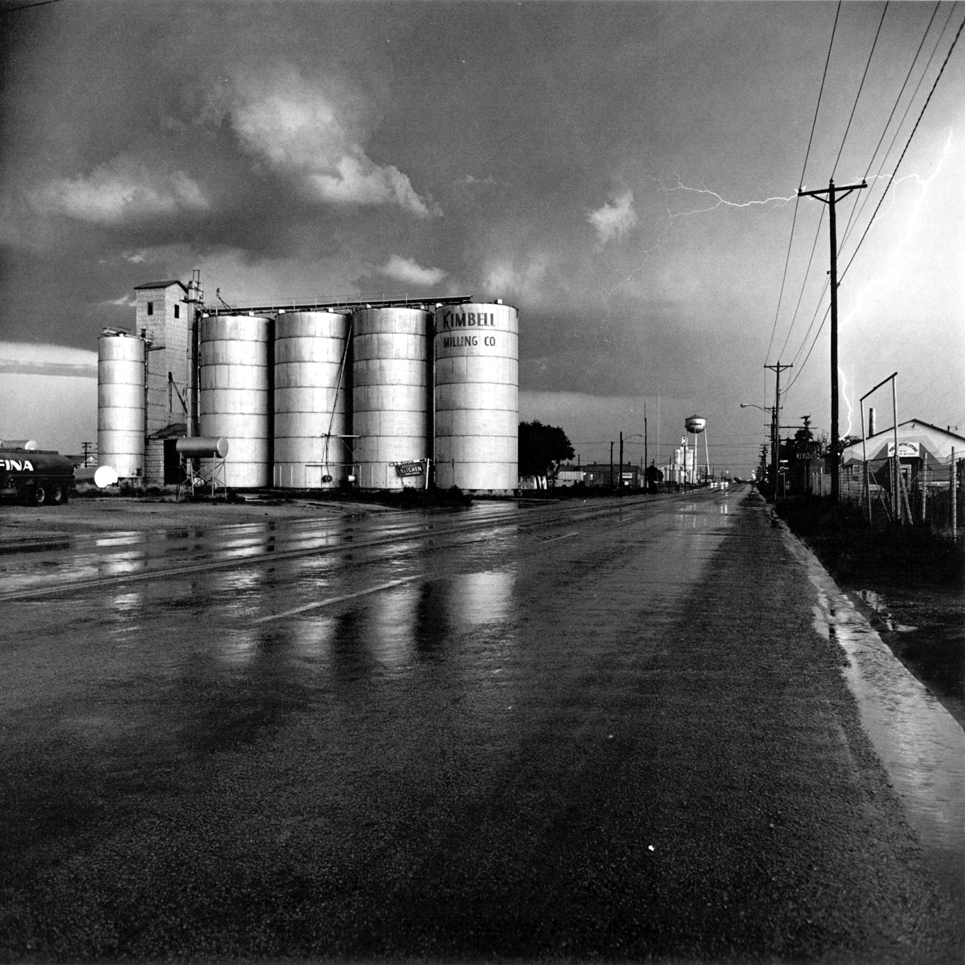

Edzell Castle: Architecture and Treatises in Late 16th Century Scotland

2022

2022

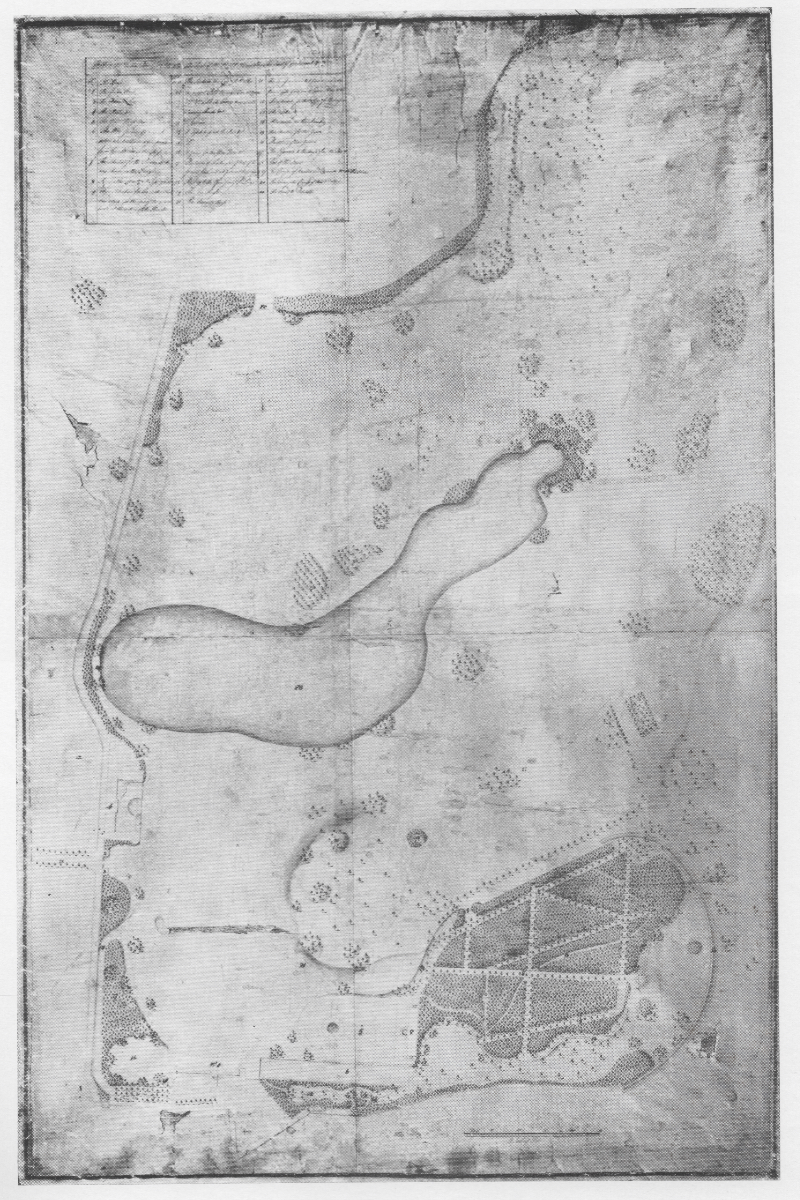

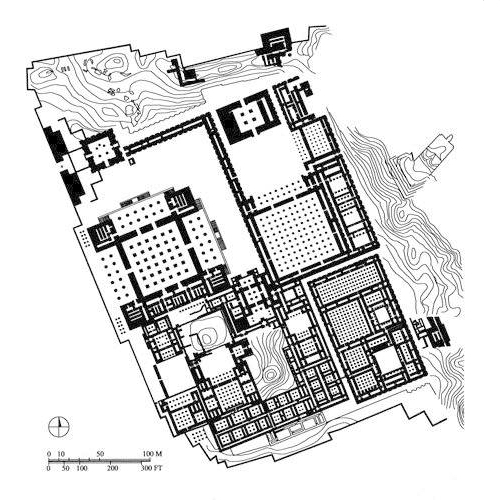

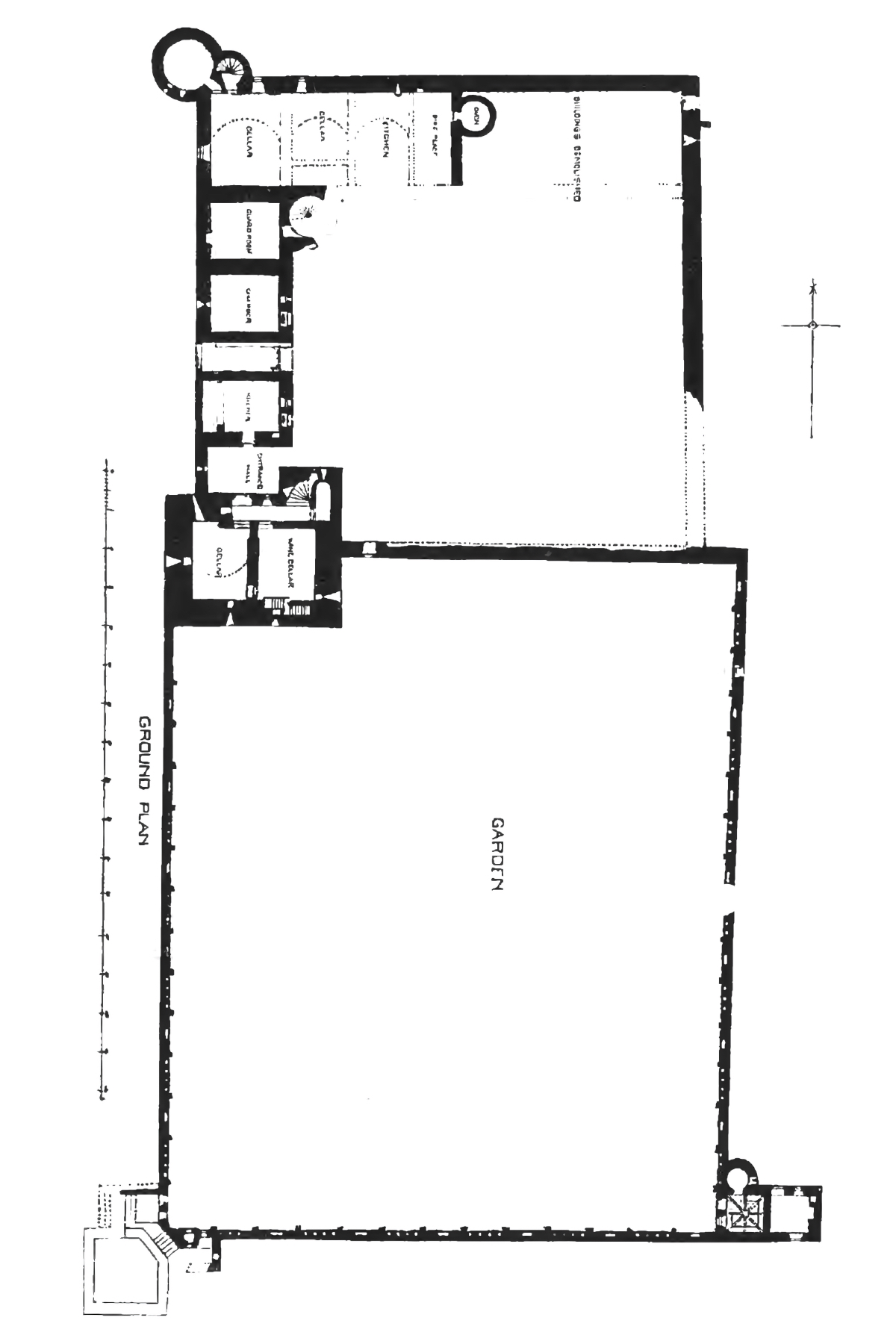

Edzell Castle, Ground Floor Plan

from MacGibbon and Ross: The Castellated and Domestic Architecture of Scotland (Edinburgh 1887)

from MacGibbon and Ross: The Castellated and Domestic Architecture of Scotland (Edinburgh 1887)

Edzell Castle: Architecture and Treatises in Late 16th Century Scotland

This article is an edited version of my article Edzell Castle: Architectural Treatises in Late 16th Century Scotland published in The Pleasaunce, 2014 for the Garden History Society (now The Gardens Trust) and expands on interests linked to my studies of tower houses with my MArch Unit at the University of Dundee and of course my own tower house studies.

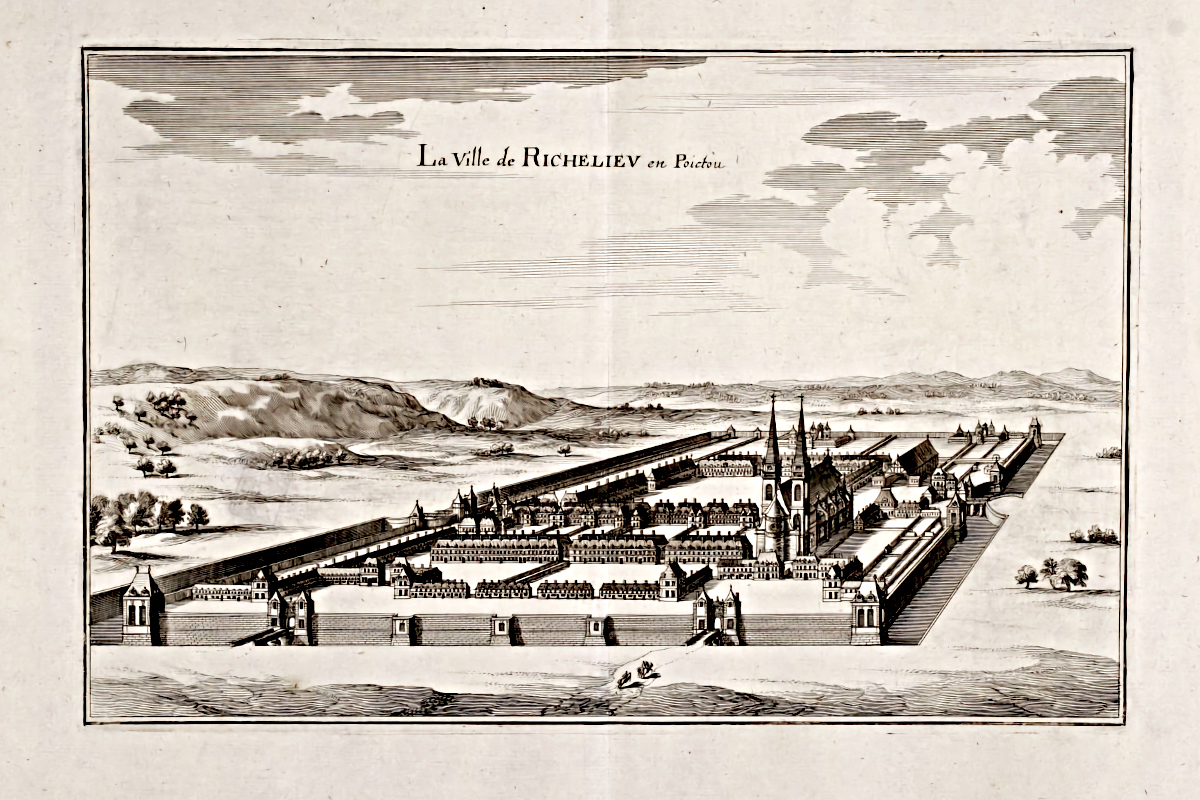

The walled garden at Edzell Castle in Angus is a remarkable survival of an early 17th century Scottish architectural garden. It was designed and built by David Lindsay, Lord Edzell (1551-1610), in conjunction with the master mason Thomas Leiper, in 1604. There has been historically much confusion as to how the garden came into existence: because the walls of the garden are decorated with carvings in a German style, the origins of the whole entreprise in the French renaissance have been overlooked. This confusion has arisen because, for art historians, questions of attribution on the basis of style are easy, while practical questions of how and why a work of architecture came into being are quite difficult to formulate.

Edzell Castle: Garden and Stirling Tower

© Thomas Deckker 2011

© Thomas Deckker 2011

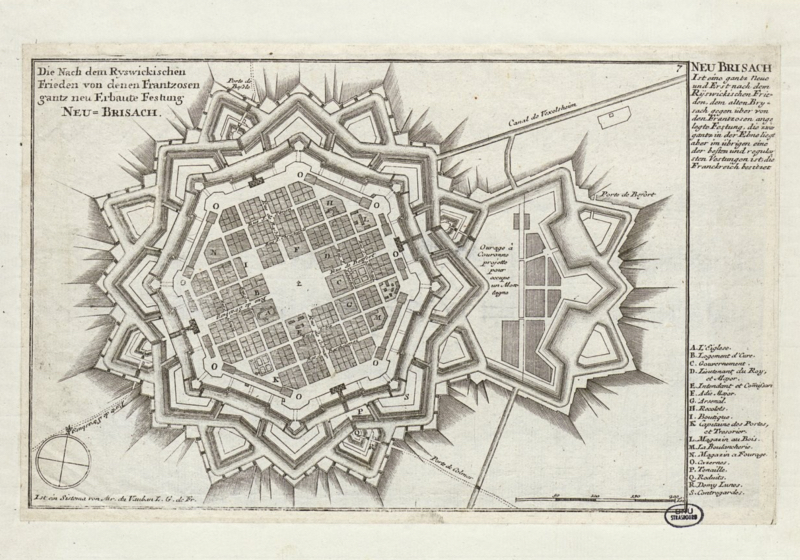

While the evidence of David Lindsay's influences, aims and ideas is fragmentary, enough remains to deduce an account that future research can only reinforce. First, and most obvious, is the formal resemblance to French renaissance gardens, which had become known through treatises. As the garden is square and biaxially symmetrical, it must have been planned rather than improvised as was usual for medieval buildings (as, for example, the Leiper garden at Tolquhon nearby). This implies an understanding of drawing and translating designs from paper to building, skills which required education and which were themselves disseminated in treatises. It contains classical motifs, symbolic of the reemergence of knowledge from the lost Greek and Roman worlds. It can be seen as part of a larger enterprise of novel and sophisticated ideas - on architecture, gardening, cooking, hygiene and even mining - that transformed civil society in Scotland at the end of the 16th century.

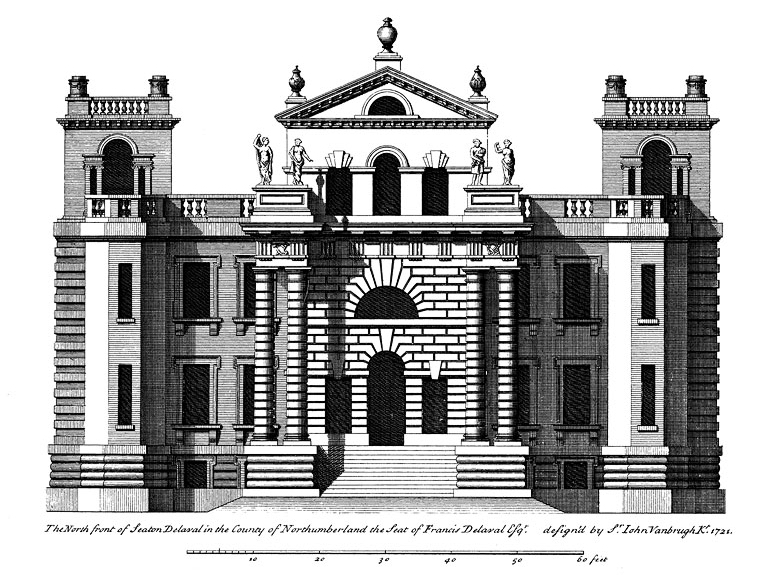

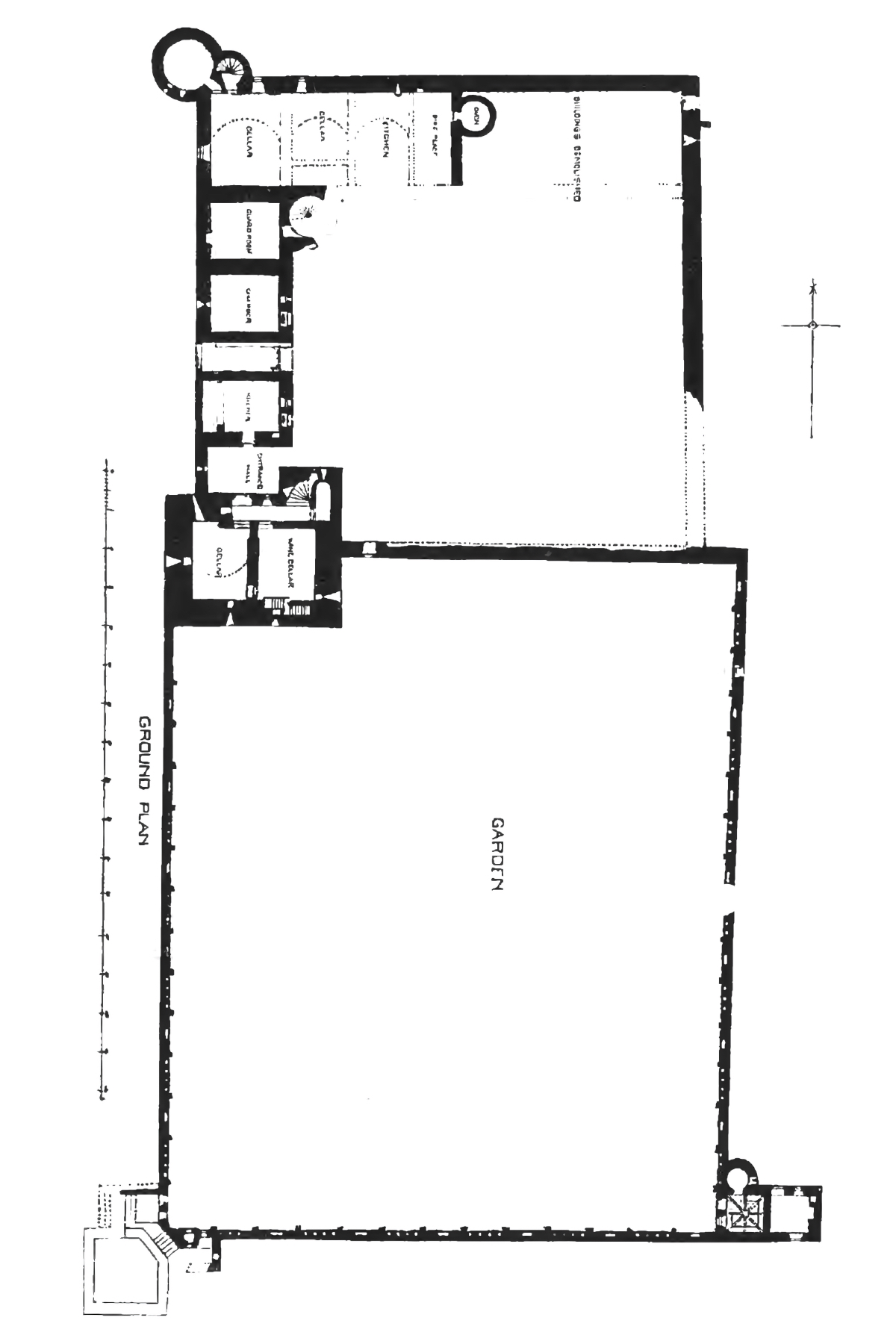

Philibert de l'Orme: Château d'Anet (1547-52) from Jacques Androuet du Cerceau: Les plus excellents bastiments de France (Paris 1576)

Roll over for the location of the bathhouse and pavilions.

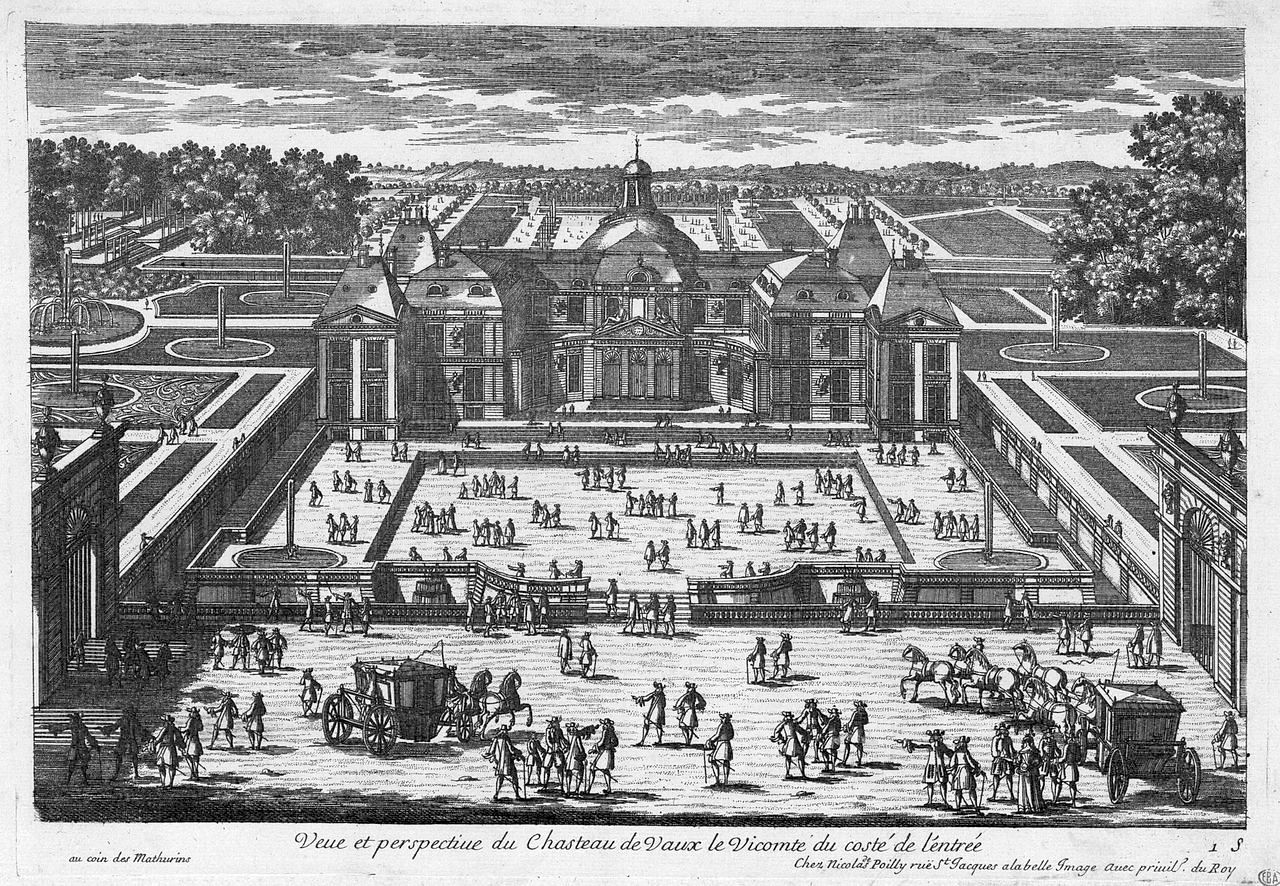

The Château d'Anet was built for Diane de Poitiers, the mistress of Henri II and an important patron af architecture. A branch of the River Eure was diverted around the garden, partly for defence and privacy but also to provide water for the bathhouse, located in the centre of the far wall between 2 pavilions. As most of the château and garden have been demolished their use cannot be determined exactly, but as they are similar to those at Edzell they may have been private retreats.

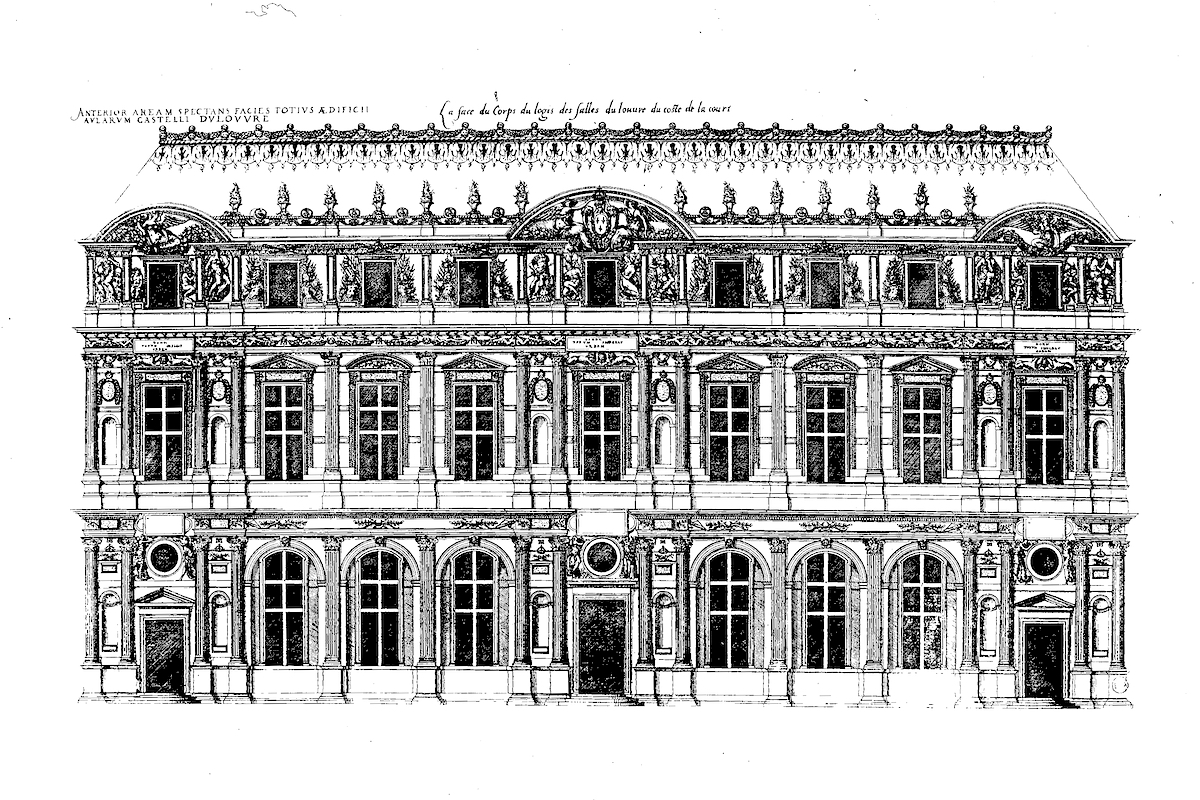

David Lindsay's main source of renaissance architecture was, on the evidence of its illustrations, the 2-volume compendium of royal palaces and châteaux Les plus excellents bastiments de France, published by Jacques Androuet du Cerceau in Paris in 1576 and 1579. David Lindsay visited Paris only briefly in 1570 so could not have seen the châteaux illustrated, but it may be inferred, both from the interests he is known to have had and from the formal similarities between Edzell and châteaux such as Bury, Chantilly and Anet, that he knew of them at some later time. We can assume that David Lindsay kept some contact with France, as he owned some important French treatises and as his brother John Lindsay, Lord Menmuir, was appointed ambassador to France in 1597.

The treatise was the principal method of communicating ideas in architecture, usually instead of visiting the buildings themselves, as, beside extensive discussion on the theoretical or practical aspects of architecture, or both, it could be used as a pattern book. Du Cerceau's Les plus excellents bastiments de France was likely to have been directed to aspiring improvers: according to Bruno Tollon (in 'Les Châteaux des guerres de Religion' in Françoise Bercé & Jean Pierre Babelon: Le château en France Paris: Caisse nationale des monuments historiques et des sites, 1986) "the engravings, true catalogues of desires, met the practical needs of, or inspired, chatelains". Possession of architectural treatises was, presumably, common among educated nobles during the late 16th century in Scotland. David Lindsay is known to have had 144 books in his library at his death in 1610. His catalogue still exists, but it is is such poor condition that most of it is indecipherable.

Garden, Edzell

© Thomas Deckker 2011

© Thomas Deckker 2011

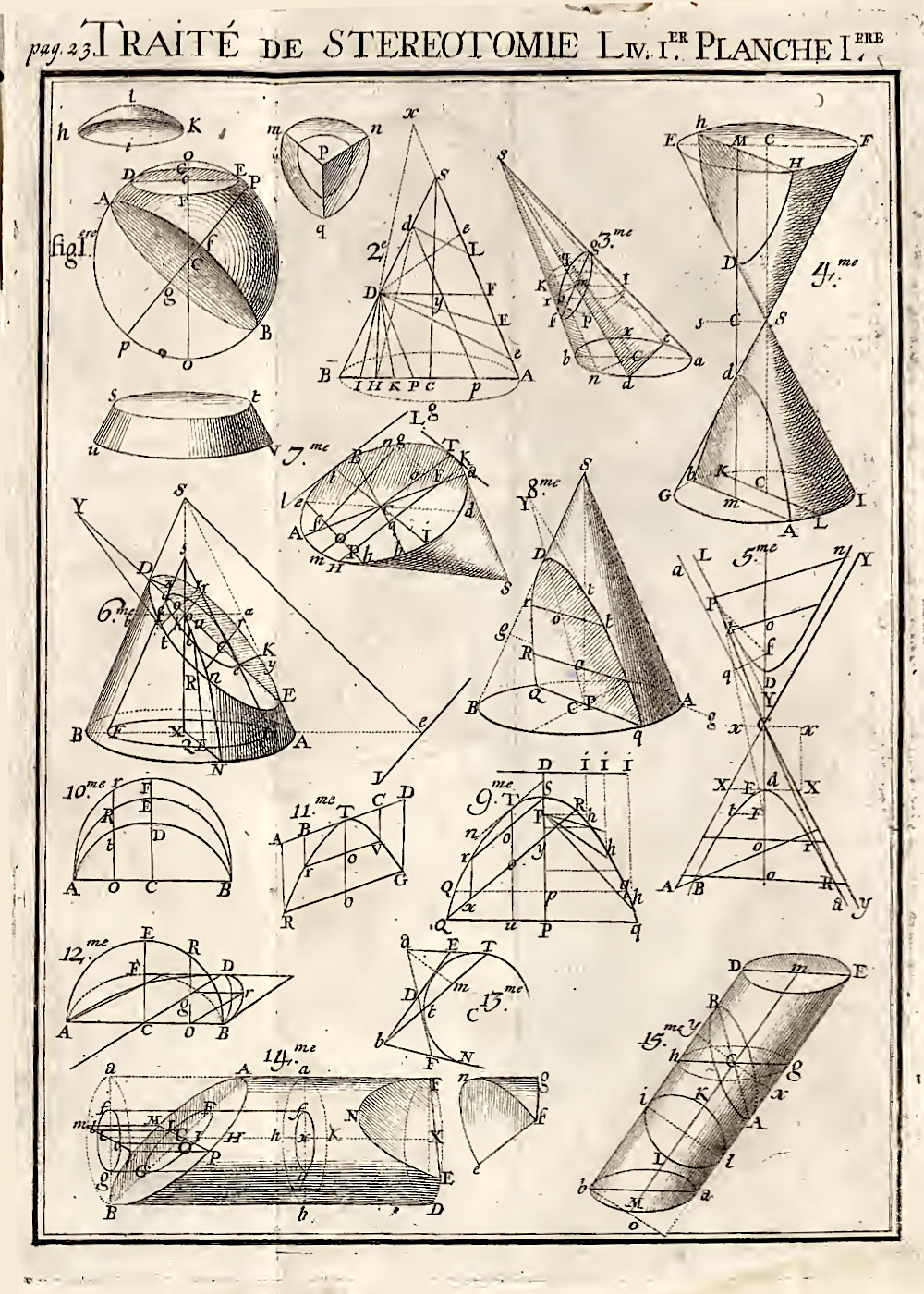

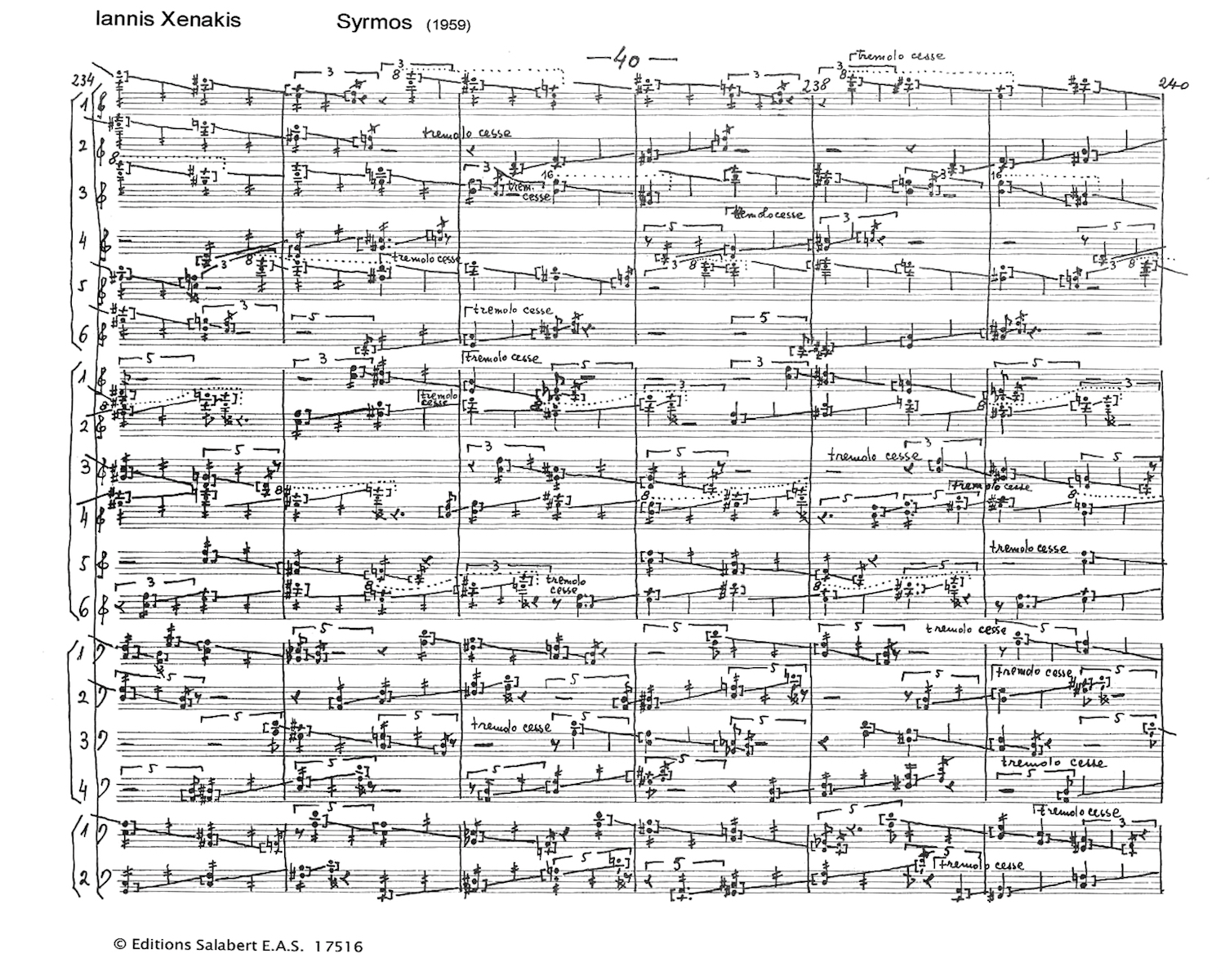

The garden walls form a slightly irregular rectangular enclosure with a single rectangular parterre, such as at the Chateau de Bury. The west, south and east walls of the garden were divided into bays articulated by shafts, now disappeared, which contained, in alternate bays, allusions to the classical world in the form of sculptured panels of the seven Liberal Arts (the trivium: grammar, logic, and rhetoric, and the quadrivium: arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy, that formed the basis of university education in the period), the seven Cardinal Virtues, and the seven Planets. According to Douglas Simpson (in Scottish Castles: An Introduction to the Castles of Scotland Edinburgh HMSO 1959), these were based on a series of engravings probably made in Nuremberg in 1528 by Georg Pencz, a pupil of the German artist Albrecht Dürer, whose initials were unwittingly carved onto a panel. This assumption, based quite reasonably on the visual similarity although no treatise or set of drawings by Dürer is known to have been in David Lindsay's possession, has led to the quite unreasonable assumption that the design of the garden as a whole was based on German precedents.

Earl David extension and Stirling Tower seen across the former moat, Edzell

© Thomas Deckker 2011

© Thomas Deckker 2011

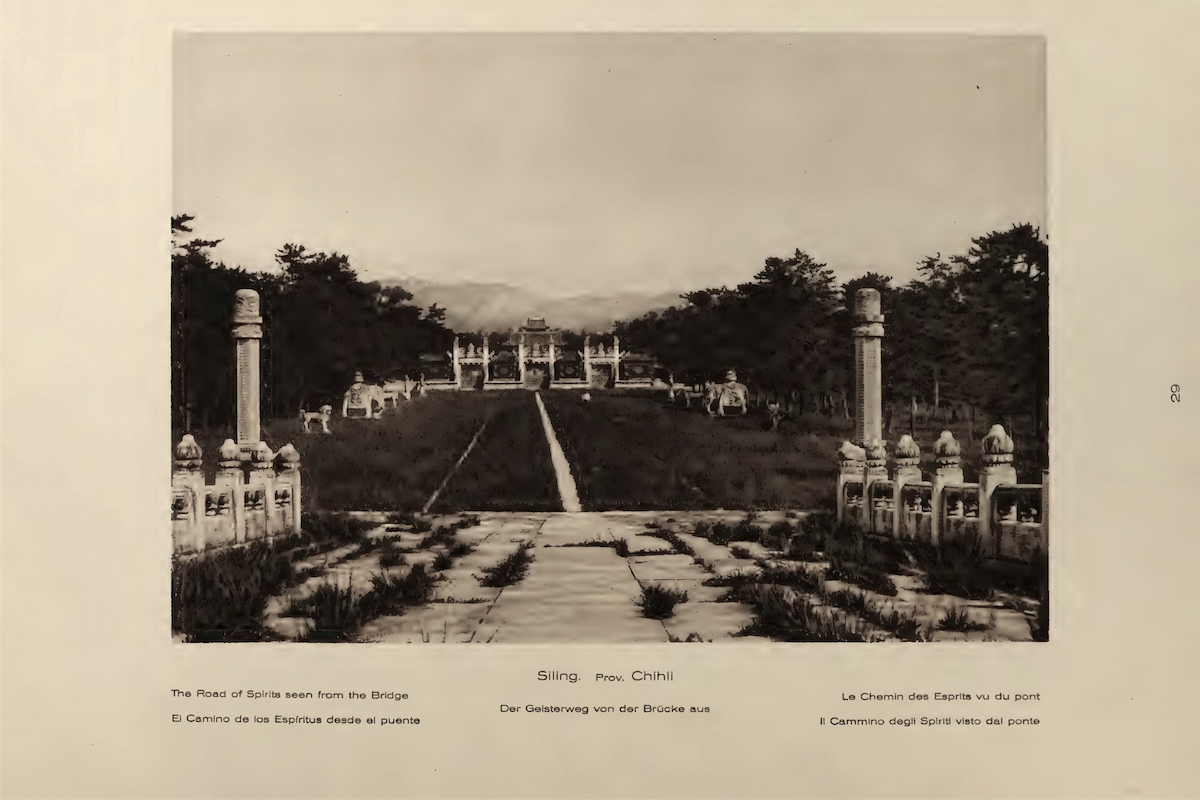

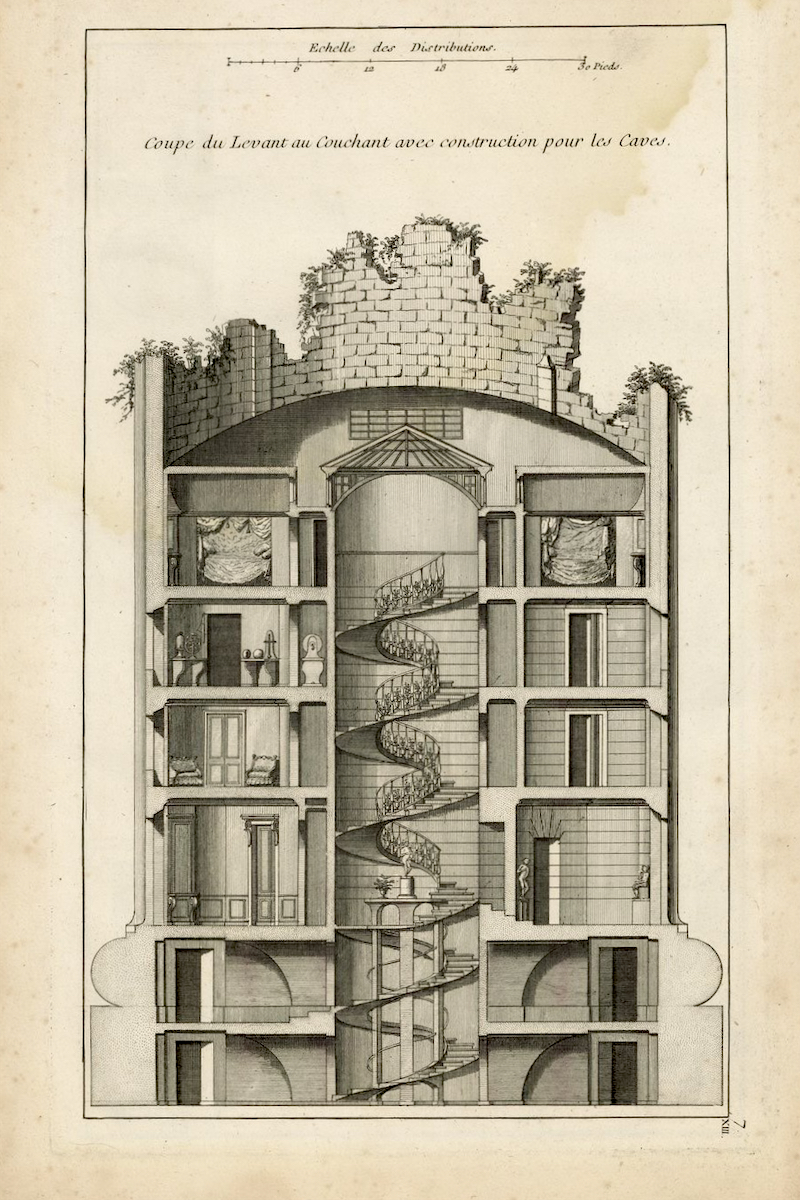

The successive stages of buildings at Edzell illustrate the developing ideas of domestic comfort in the renaissance. The original tower house, the Stirling Tower, was built c. 1520; it was extended by Lord Edzell's father, Earl David, with a two-storey block containing a formal entrance (possibly over a moat, now disappeared) flanked by guardrooms with a withdrawing room, private room and anteroom over. These three rooms reflected the contemporary French arrangement of salon, chambre and cabinet and indeed one of these rooms, according to Andrew Jervise (in The Land of the Lindsays in Angus and Mearns, with Notices of Alyth and Meigle Edinburgh 1853), was named the 'Queen's Chamber' in honour of a visit from Mary, Queen of Scots, in 1562. Mary had, of course, grown up in the Loire, the centre of the French renaissance, and was an intimate friend of Diane de Poitiers, an important patron of architecture, who commissioned both Anet and the bridge at Chenonceau from Philibert de l'Orme. It requires no stretch of the imagination to see Mary as the conduit and inspiration for the introduction of French renaissance ideas into Scotland.

François Clouet: A lady in her bath, c.1571 [sitter unknown, possibly Diane de Poitiers]

National Gallery of Art, Washington 1961.9.13

National Gallery of Art, Washington 1961.9.13

David Lindsay extended the earlier buildings with a northern wing to form a courtyard; this wing containing a very large vaulted kitchen and two vaulted store rooms on the ground floor, with, in a conjectural restoration by McGibbon and Ross, a hall and two rooms over. The upper floor would have been well warmed, without any doubt, by the enormous flue from the kitchen passing through it. The hall was reached by a formal stair in the re-entrant corner and a service stair from the store below. Remains of smaller buildings forming the southern and eastern walls of the courtyard may be seen. By 1589, then, David Lindsay had a lightly fortified house incorporating all the latest modern conveniences, presumably in anticipation of the visit of James VI that year.

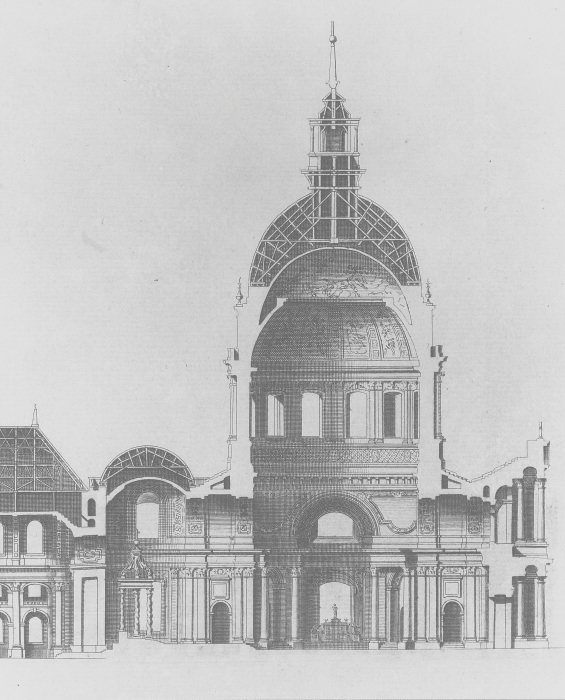

Philibert de l'Orme: Château de Chenonceau (commissioned by Diane de Poitiers) 1555

© Thomas Deckker 1984

© Thomas Deckker 1984

Jardin de Diane de Poitiers, Château de Chenonceau

© Thomas Deckker 1984

© Thomas Deckker 1984

French renaissance chateaus, such as Chenonceau, were a mixture of gothic forms (such as symbolic round towers) with rigorous internal planning based on a new appreciation of the arts of civilisation. The demand for new types of garden was driven by new conceptions of leisure and private life for a new class of ministers - lawyers, administrators and financiers - rather than feudal nobility. Architects developed the plans of châteaux and hôtels to accommodate these new conceptions, embodied in the idea of distribution [the arrangement of rooms]: as Jean-Marie Pérouse de Montclos noted in L'architecture à la française: XVIe, XVIIe, XVIIIe siècles (Paris: Picard, 1982):

Le Français ont attaché une importance toute particulière aux questions de distribution et il semble qu'ils aient eu l'ambition de donner sur ce point des modèles susceptibles d'être diffusés au-delà des frontières.

This was certainly taken up in Scotland: as Charles McKean noted, in The Scottish chateau: the country house of renaissance Scotland (Stroud: Sutton, 2001):

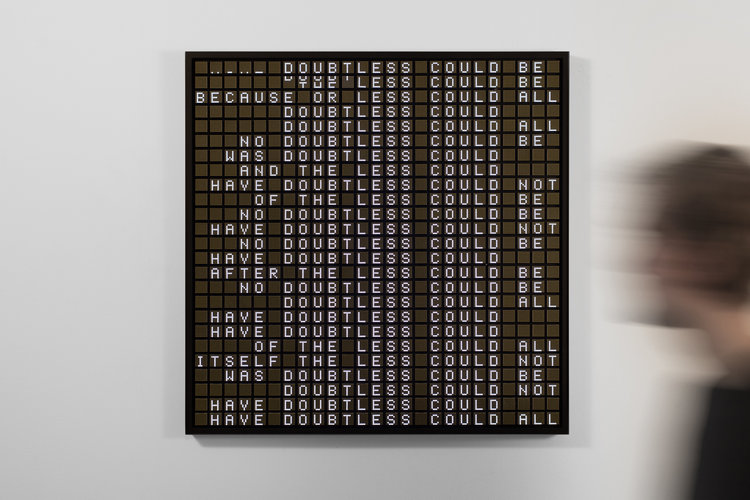

Architecture was one of the principal ways in which the nobility contributed to the national cultural obsession with the reinterpretation and reinvention of history. Yet it was but an 'imposing mask' - for display only. Behind it, their plans were wholly unsentimental in their rejection of the communal life of the Middle Ages.

Summer House, Edzell

© Thomas Deckker 2011

© Thomas Deckker 2011

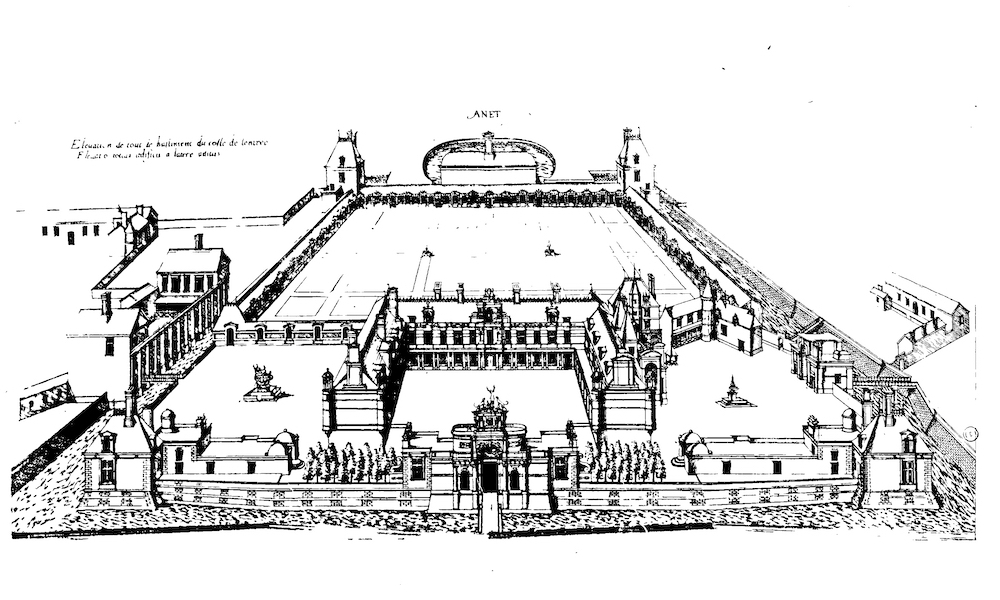

Gardens were also an integral part of the improved practices of agriculture and the new practices of gardening, cooking, hygiene and medicine, exemplified by the treatise La Maison Rustique by Charles Estienne with illustrations by Jean Liébault published in Paris in 1589, known to have been owned by David Lindsay. This treatise defined all the most modern agricultural necessities for running a country house, which presupposed a less martial and more educated nobility, and was associated with the more prominent role of women in household management in the renaissance. Edzell had extensive gardens and a forest for hunting, and, according to Peter Davidson (in 'Edzell Garden and the Lindsay Libraries' in The Pleasaunce, 2014) an English chef and gardener. The dining and bathing pavilions in the garden indicate that David Lindsay was interested in these arts of civilization and doubtless the forest and gardens supplied them. In short, despite its present appearance as a ruined castle, Edzell represents the comprehensive introduction of the humanist ideals of the renaissance into Scotland.

Charles Estienne & Jean Liébault: La Maison Rustique: Title Page

David Lindsay is known to have owned this treatise.

Charles Estienne: La Maison Rustique (Paris 1564; 2nd edition rev. by Jean Liébault, Paris 1589)

David Lindsay is known to have owned this treatise.

Charles Estienne: La Maison Rustique (Paris 1564; 2nd edition rev. by Jean Liébault, Paris 1589)

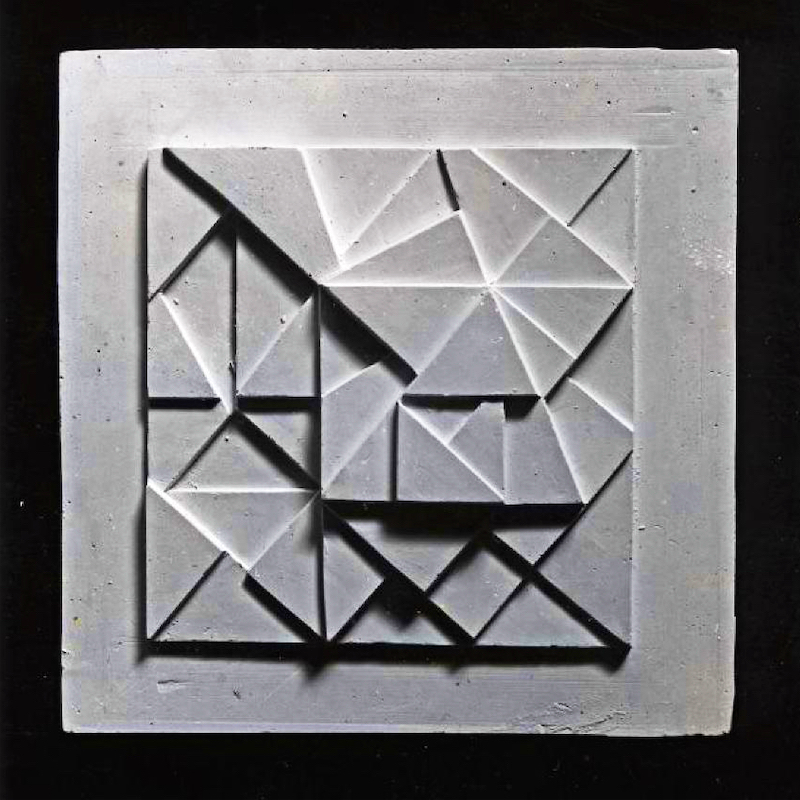

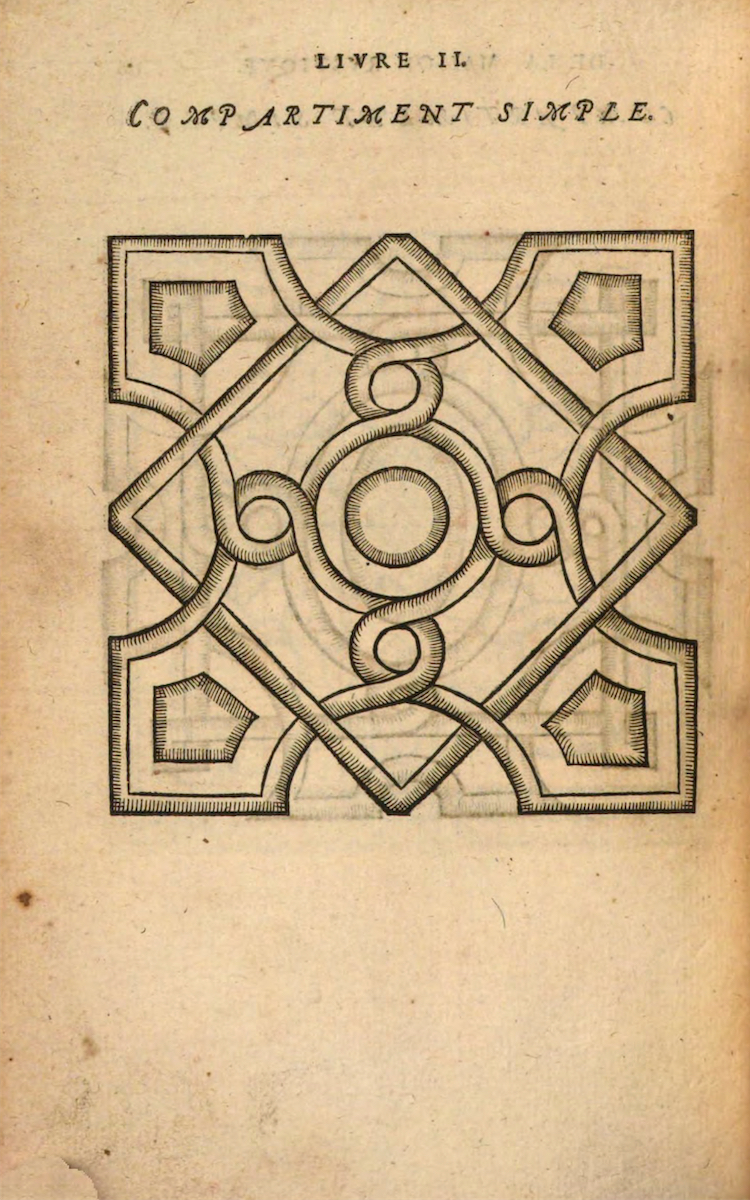

Charles Estienne & Jean Liébault: La Maison Rustique: simple parterre

The patterns for parterres promoted by Estienne were not only, or even principally, aesthetic, but bound up in practical concerns of floriculture for the new concepts of cuisine, health and hygiene that arose in the renaissance.

Charles Estienne: La Maison Rustique (Paris 1564; 2nd edition rev. by Jean Liébault, Paris 1589)

The patterns for parterres promoted by Estienne were not only, or even principally, aesthetic, but bound up in practical concerns of floriculture for the new concepts of cuisine, health and hygiene that arose in the renaissance.

Charles Estienne: La Maison Rustique (Paris 1564; 2nd edition rev. by Jean Liébault, Paris 1589)

The Summer House, Edzell

© Thomas Deckker 2011

© Thomas Deckker 2011

Footnotes

1. Further research into David Lindsay's short visit to Paris has shown that he could have seen the Lescot Wing of the Louvre, illustrated in Du Cerceau's Les plus excellents bastiments de France. I have edited the text here to make it clear he could not have see the chateaus only. ↩

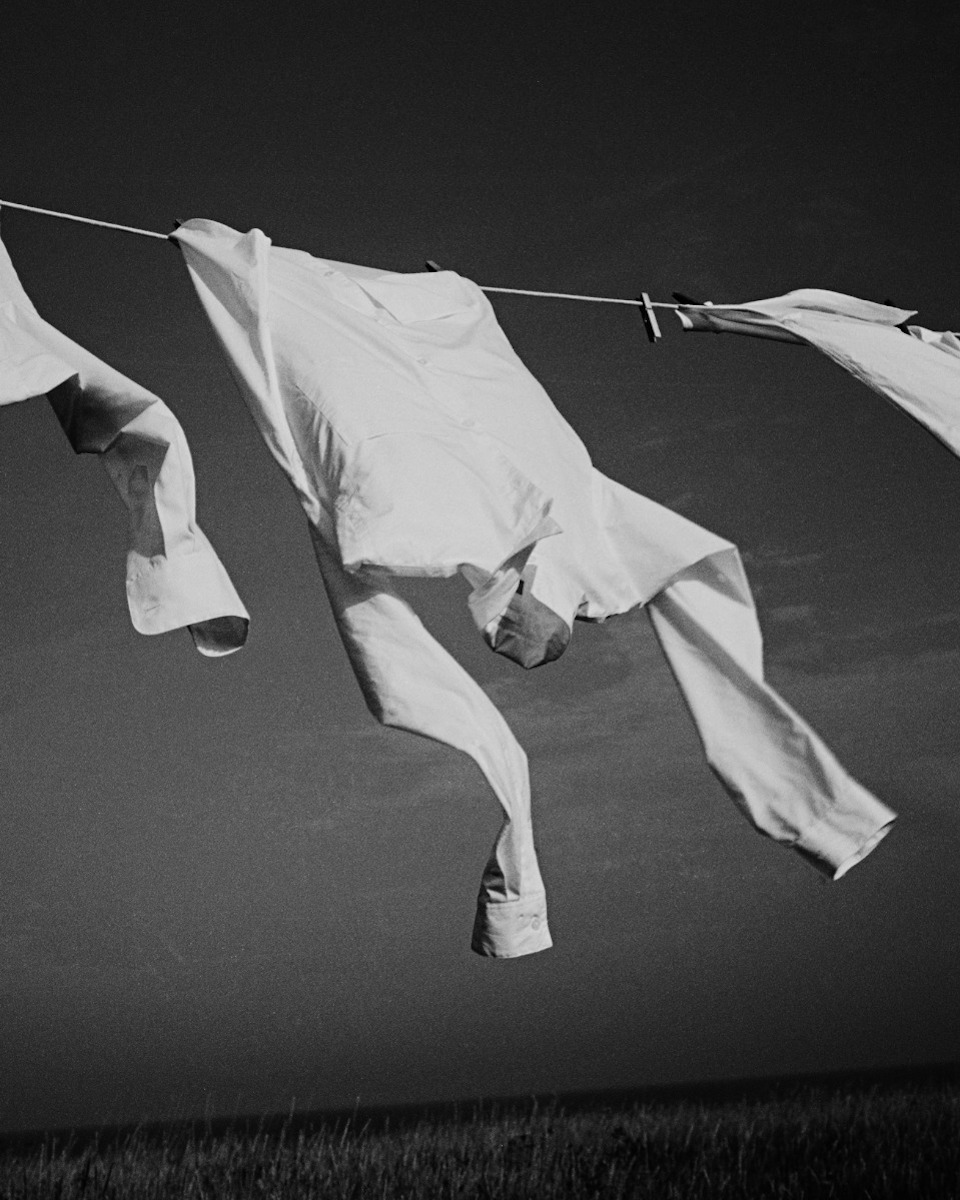

What did they wear?

Woman's Waistcoat, c. 1610

This jacket is an example of formal daywear worn by wealthy Englishwomen in the early 17th century. The embroidery is based on designs from pattern books, herbals and emblem books.

Victoria & Albert Museum Accession Number T.228-1994

Acquired with the assistance of the National Heritage Memorial Fund, The Art Fund and contributors to the Margaret Laton Fund

This jacket is an example of formal daywear worn by wealthy Englishwomen in the early 17th century. The embroidery is based on designs from pattern books, herbals and emblem books.

Victoria & Albert Museum Accession Number T.228-1994

Acquired with the assistance of the National Heritage Memorial Fund, The Art Fund and contributors to the Margaret Laton Fund

Dame Catherine Campbell, mother of David and John Lindsay, was, according to Alexander Lindsay (in Lives of the Lindsays; or a Memoir of the Houses of Crawford and Balcarres London 1858) an educated woman and dedicated mother. It's easy to think of Dame Catherine wearing this garment, which, although English, is contemporaneous with the garden. The patterns were, of course, a symbol of fertility as well as embodying wealth and social status. They were derived from treatises like La Maison Rustique.

Thomas Deckker

London 2022

London 2022