I find most of what is called ‘public art’ artistically banal and patronising to its audience. I think that it denigrates the public realm in which it is placed, and exposes the limits and drawbacks of patronage by bureaucratic administrative organisations. The works exist only to gain funding from these organisations, who are happy that they have something administratively acceptable to fund. The so-called ‘interpretations’ of social relevance that often accompany ‘public art’ could easily replace the works themselves, thus rendering the work of art pointless.

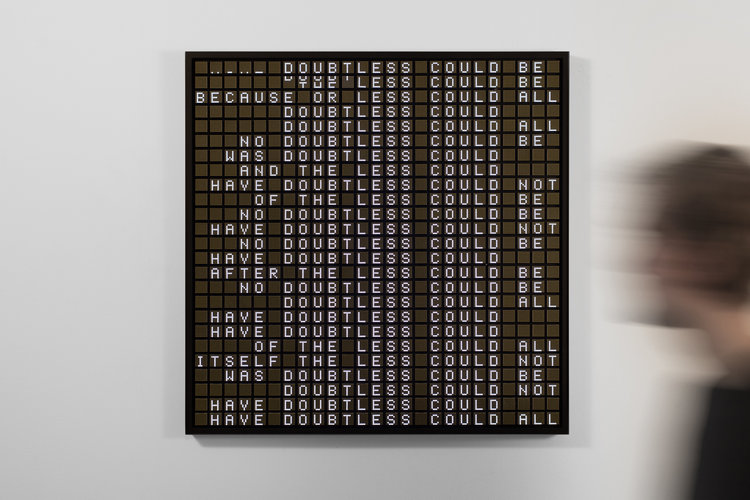

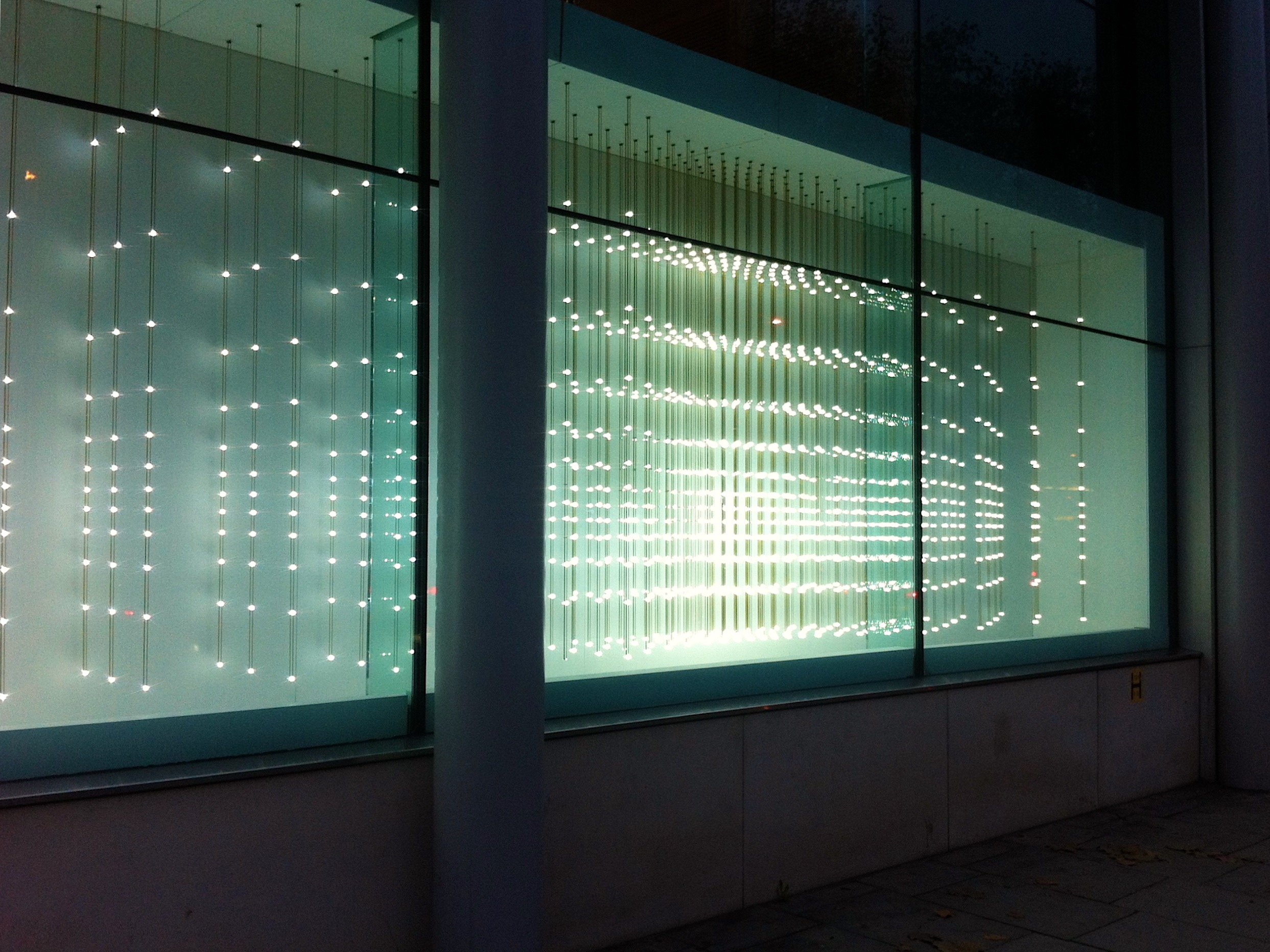

On the other hand, I think United Visual Artists have produced the best art for public involvement in recent years. I first became aware of them with 'Swarm', exhibited in a window on the Euston Road of the wonderful Wellcome Collection in 2011. 'Swarm' consisted of a display of lights controlled by an algorithm that represented and mimicked the swarming of birds, with sensors that responded to people on the street. The Wellcome Collection consistently hold outstanding exhibitions on architecture, in many respects more interesting that architectural galleries.

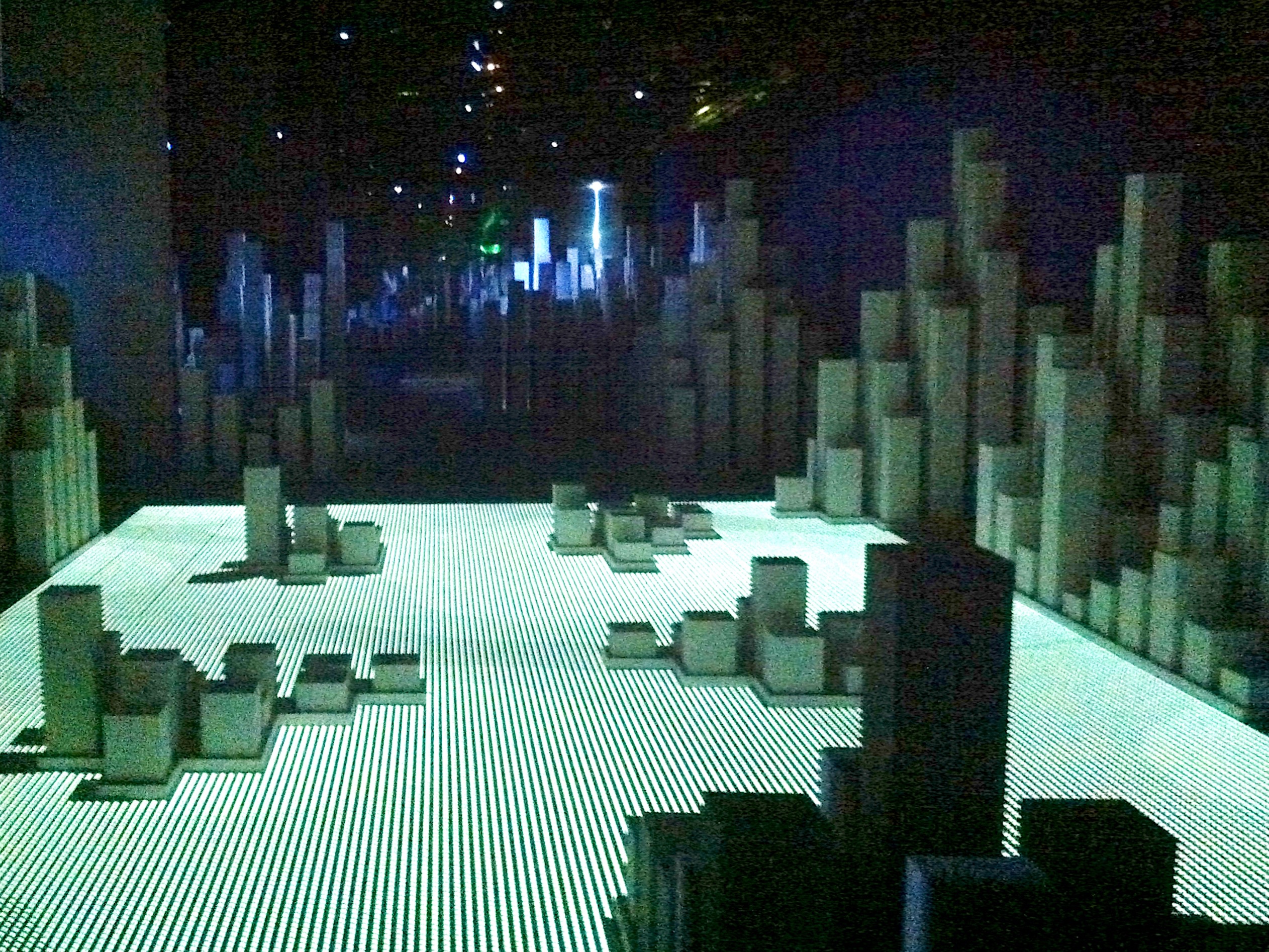

This prompted me to visit 'High Arctic' at the National Maritime Museum the same year. 'High Arctic' was an interactive exhibition of fixed wooden blocks representing icebergs and video projections of maps and icebergs on the floor, set in a black box. Sensors tracked people's movement, to which the video projections responded by bringi in images and texts. This was a time when the National Maritime Museum saw its purpose as exhibiting martime objects rather than political posturing.

'Momentum' at the Barbican Gallery in 2014 was deservedly popular, with long queues to enter. It consisted of continuous rain that was controlled by sensors to avoid people underneath. It was a wonderful sensory experience, transforming our appreciation of rain which typically seems to fall only on ourselves.

The strength of this work, I think, lies on the one hand in its sensory and corporeal nature, and on the other in the interaction of physical and electronic processes. It's so refreshing to not have to put up with 'social relevance' or 'personal expression', typical of ‘public art’.

UVA may be found here. For the avoidance of doubt these opinions are not sponsored or supported by UVA.

thomas

deckker

architect