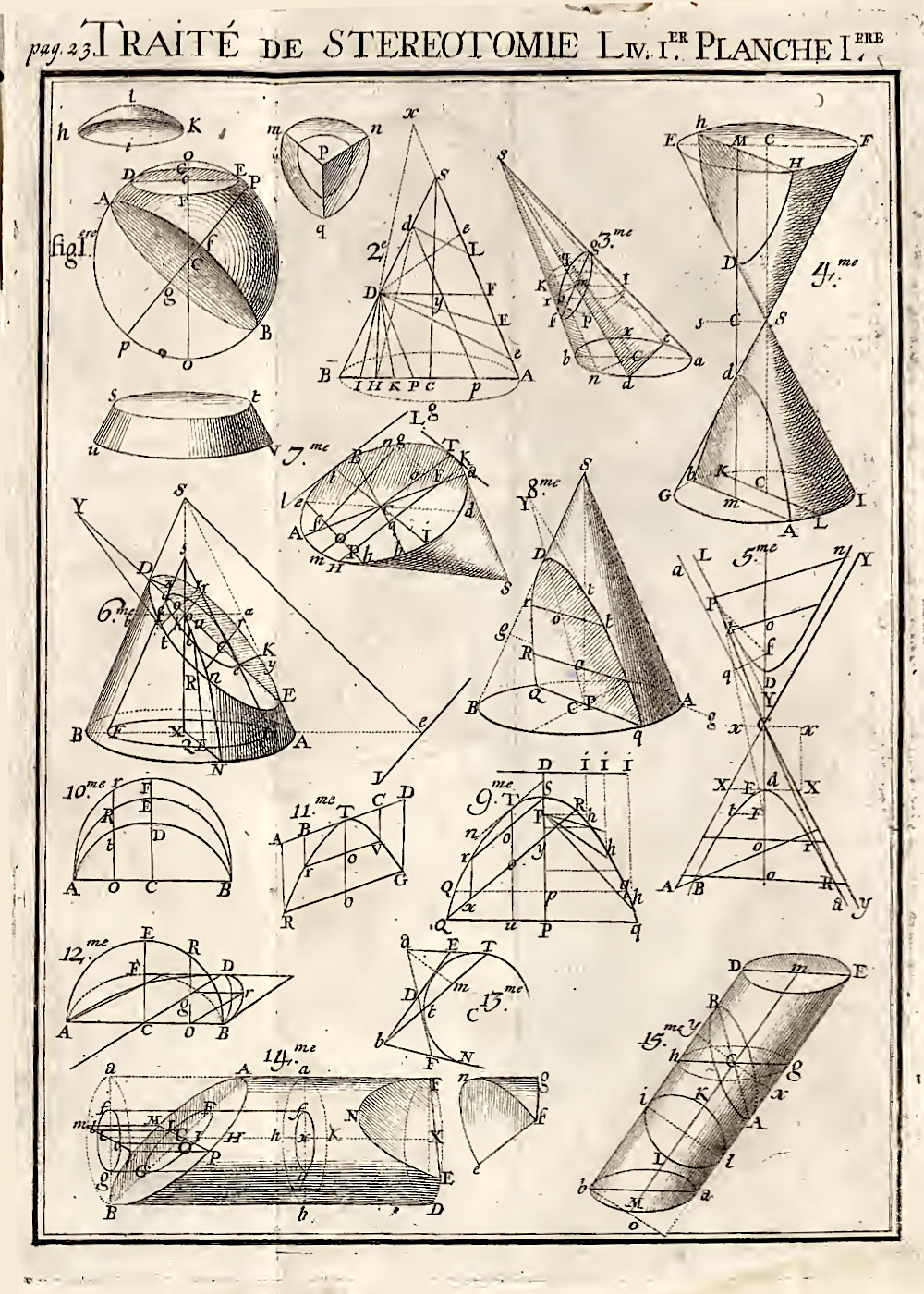

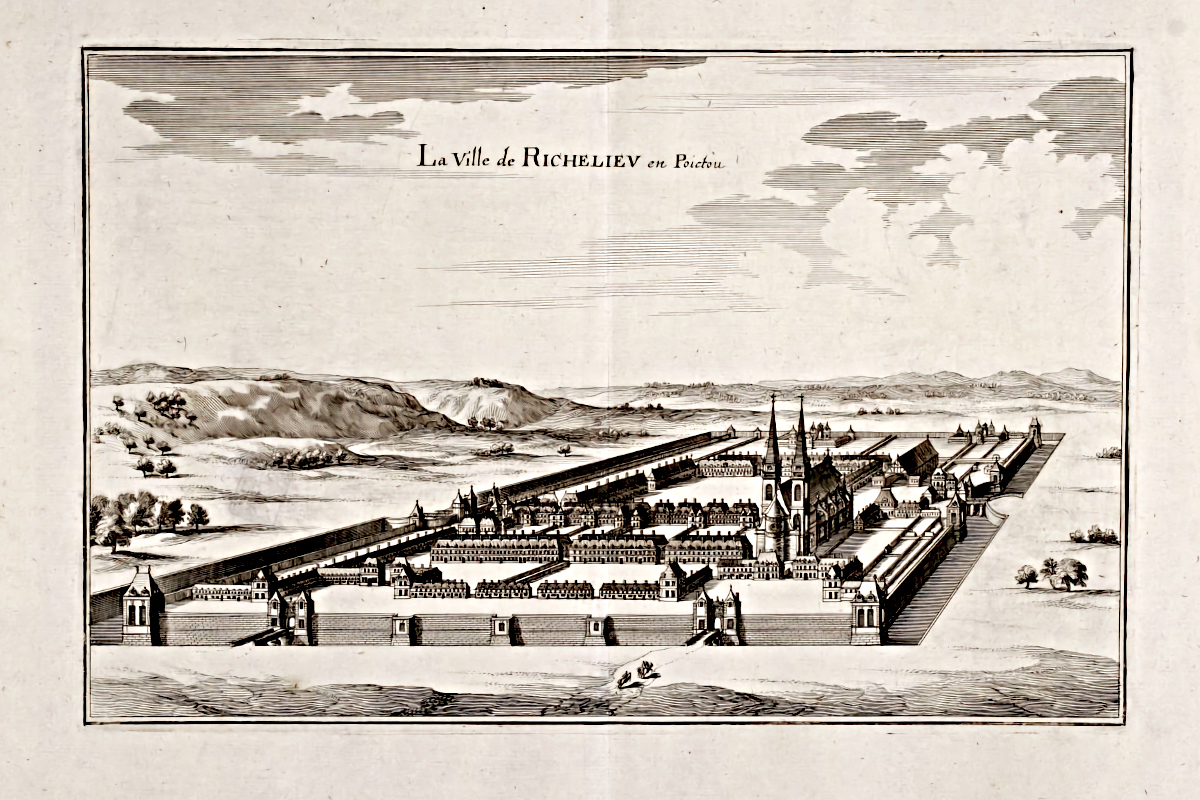

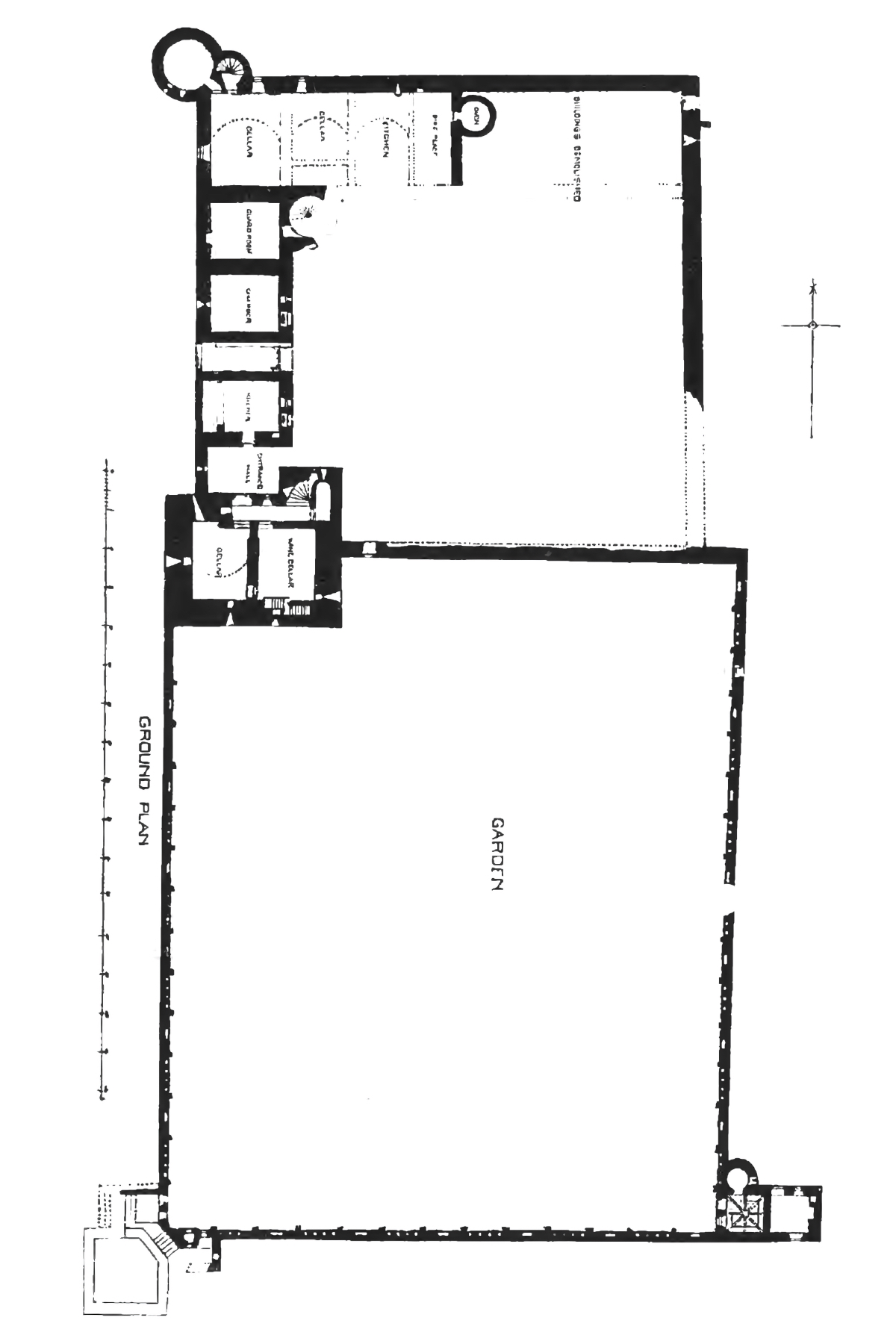

Mathias Goeritz: La serpiente de El Eco, 1953

© Sothebys

Mathias Goeritz: 'Emotional Architecture'

I discovered the work of Mathias Goeritz from

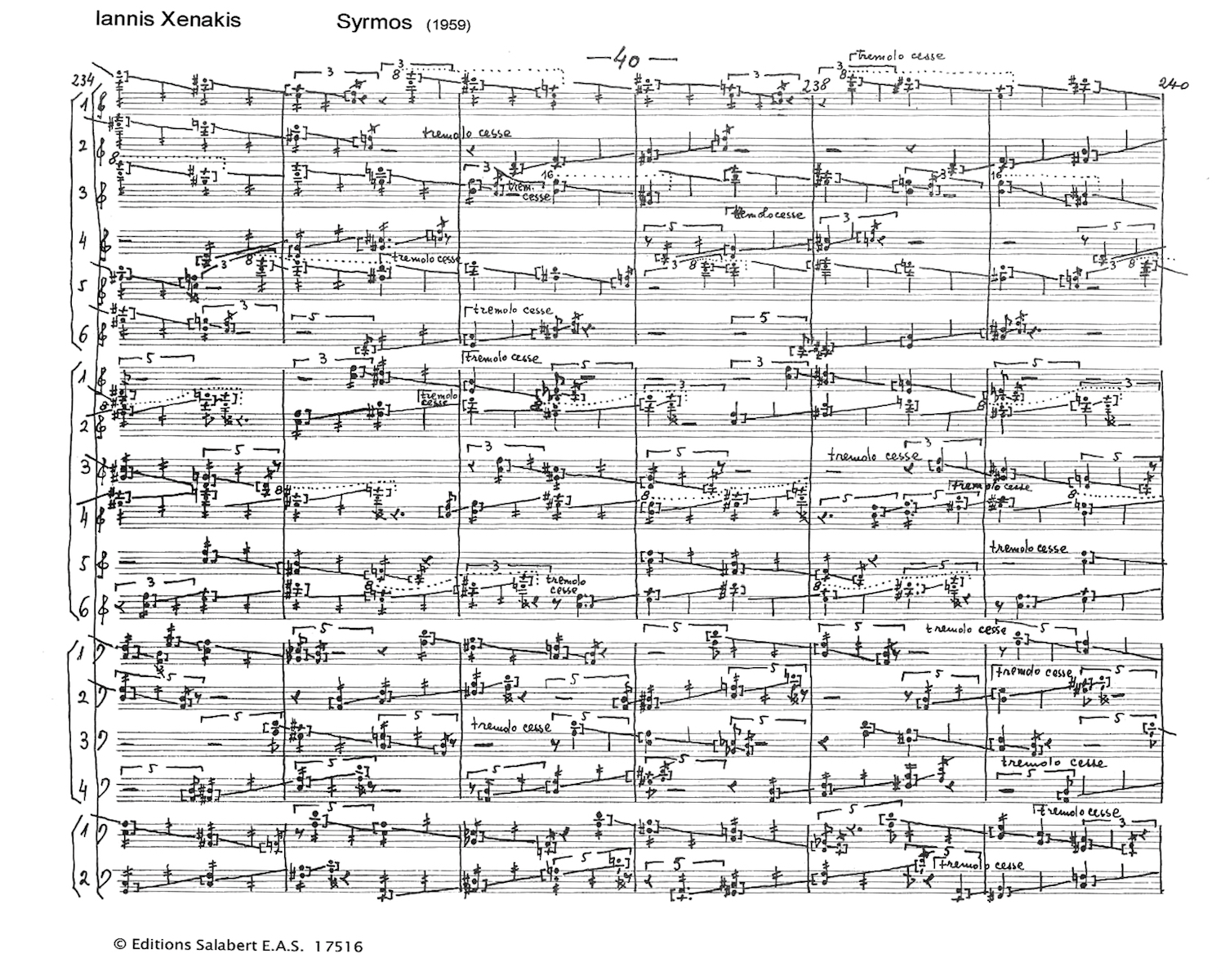

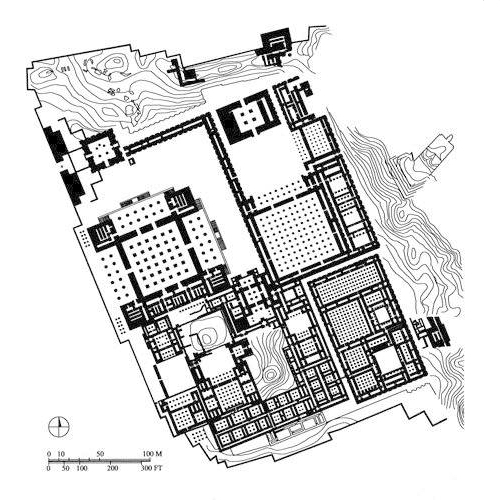

Builders in the Sun, a book on Mexican architects by Clive Bamford Smith, as a byproduct of looking for the work of his friend and occasional collaborator Luis Barragan. Goeritz began a series of sculptures called 'Emotional Architecture' in 1953, beginning with El Eco, a small building in Mexico City. The design of El Eco was purely concerned with space and the emotions raised in space such as intimacy and discovery. It was a reaction to the functionalism then dominating modern architecture worldwide and to the socialist realism then dominating art in Mexico. The plan was very simple: it included a patio with a freestanding wall, and a triangular entrance space (Barragan used similar triangular spaces in his Convento de las Capuchinas Sacramentarias in 1955). Goeritz designed a cast iron sculpture for the patio that became known as 'La serpiente', which was produced in several variants. El Eco lasted only a few years, but was rebuilt in 2005 and is now a

museum.

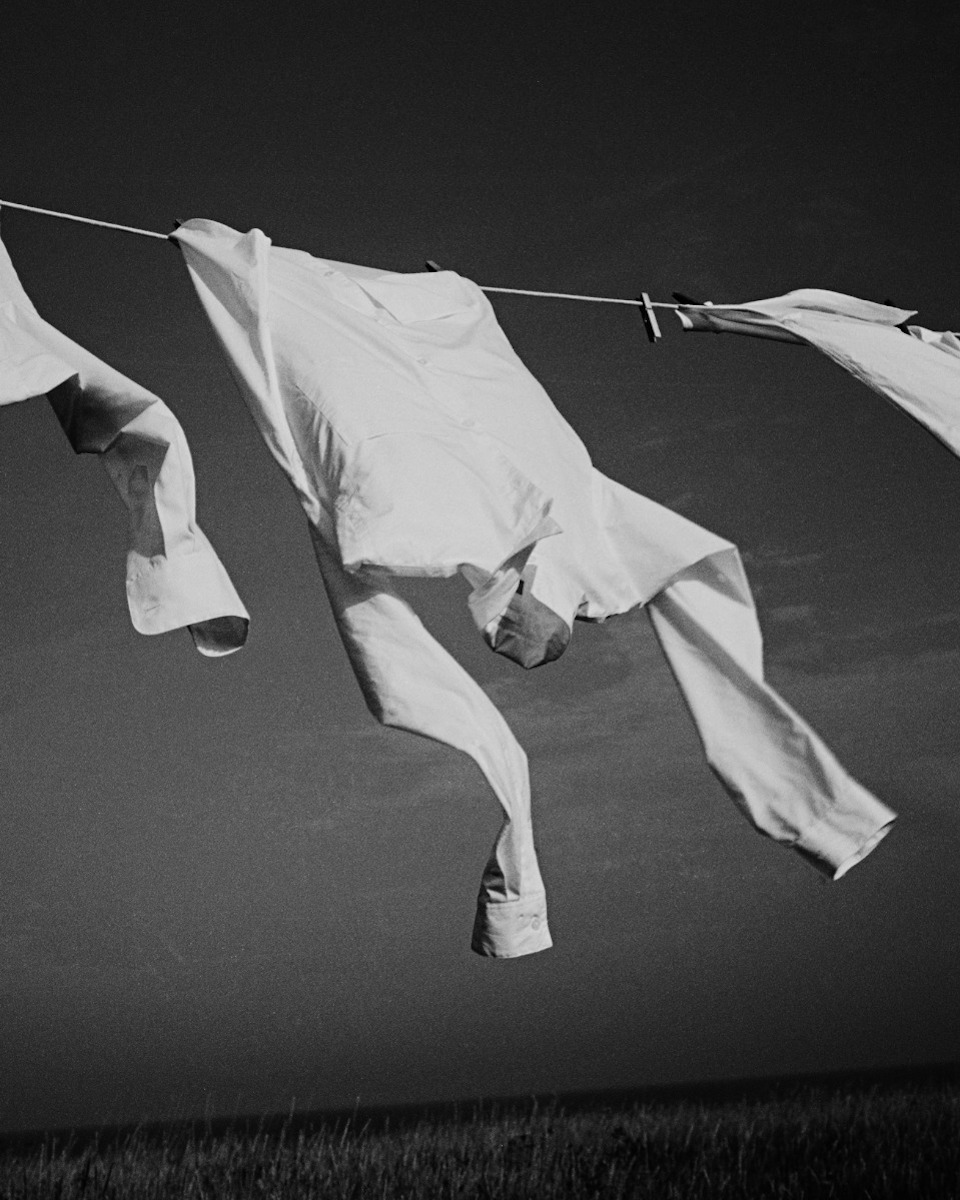

Goeritz was fortunate to be part of an artistic environment that included not only Barragan but the photographers Marianne Goeritz (his wife) and Armando Salas Portugal, the dancer Pilar Pellicer and the muralist Carlos Mérida. Marianne Goeritz and Salas Portugal were important interpreters and conduits for Goeritz's work.

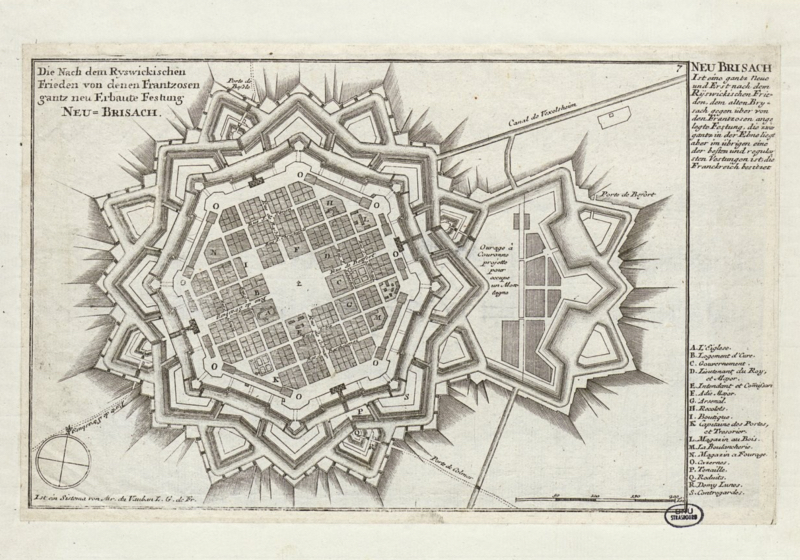

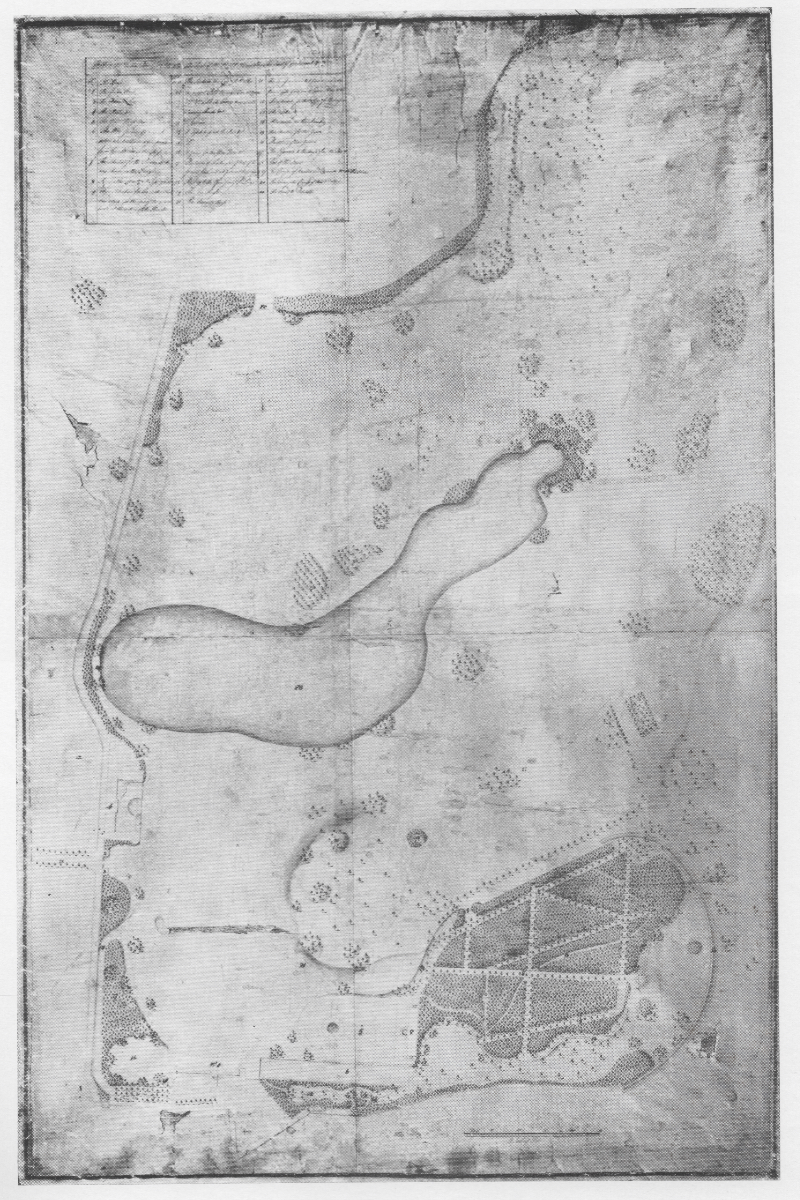

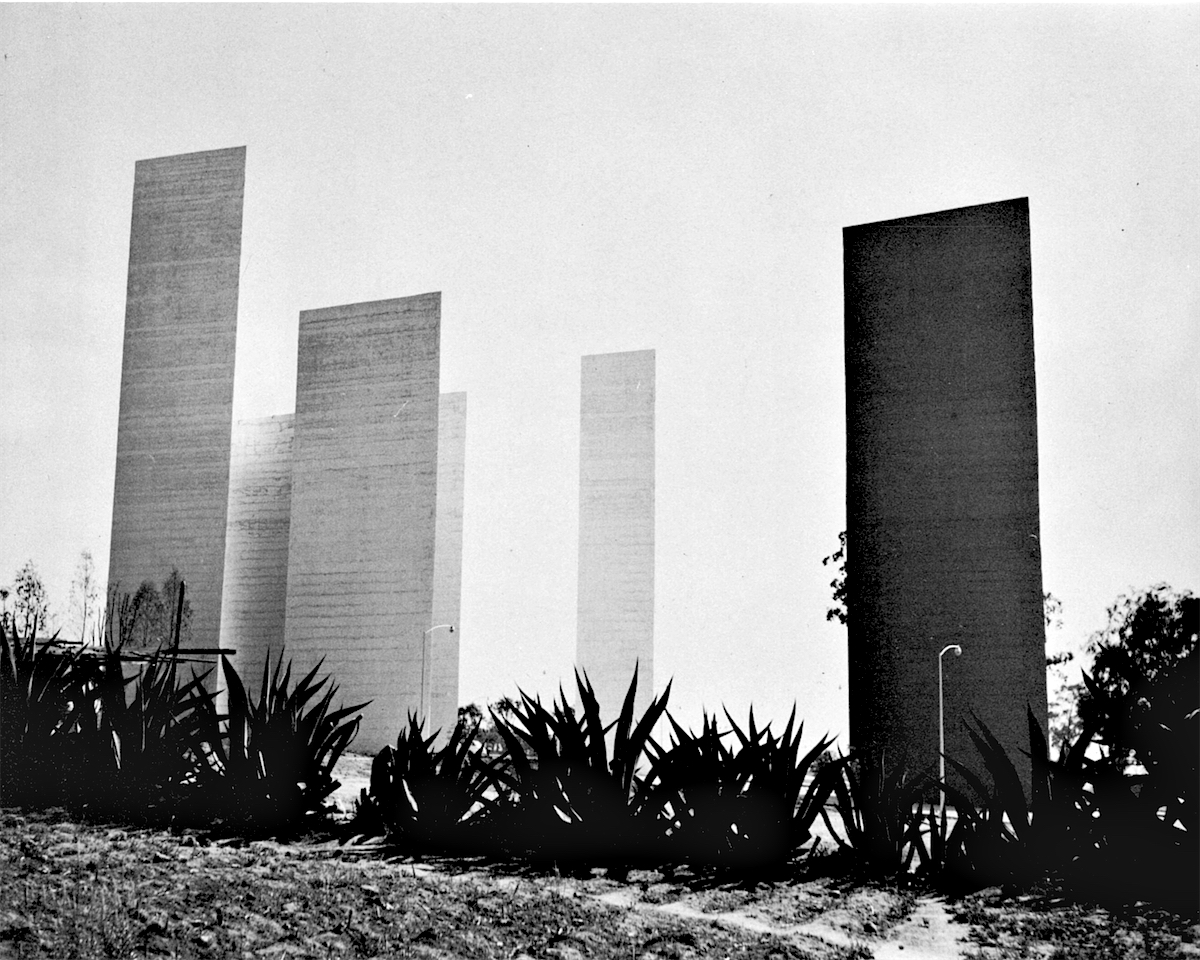

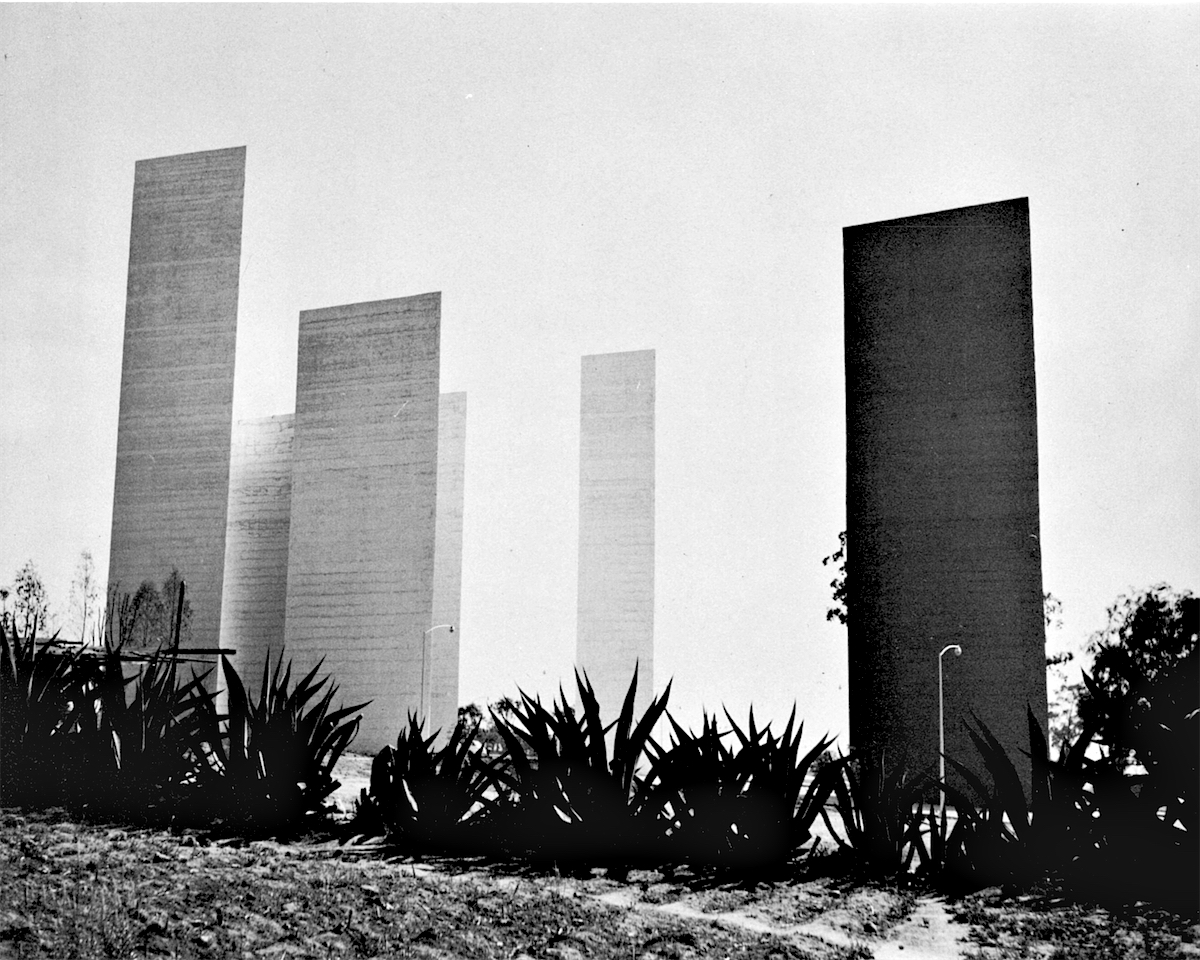

Mathias Goeritz: 'Torres de Satélite, Mexico City 1957

© Clive Bamford Smith: Builders in the Sun. Photo by Marianne Goeritz.

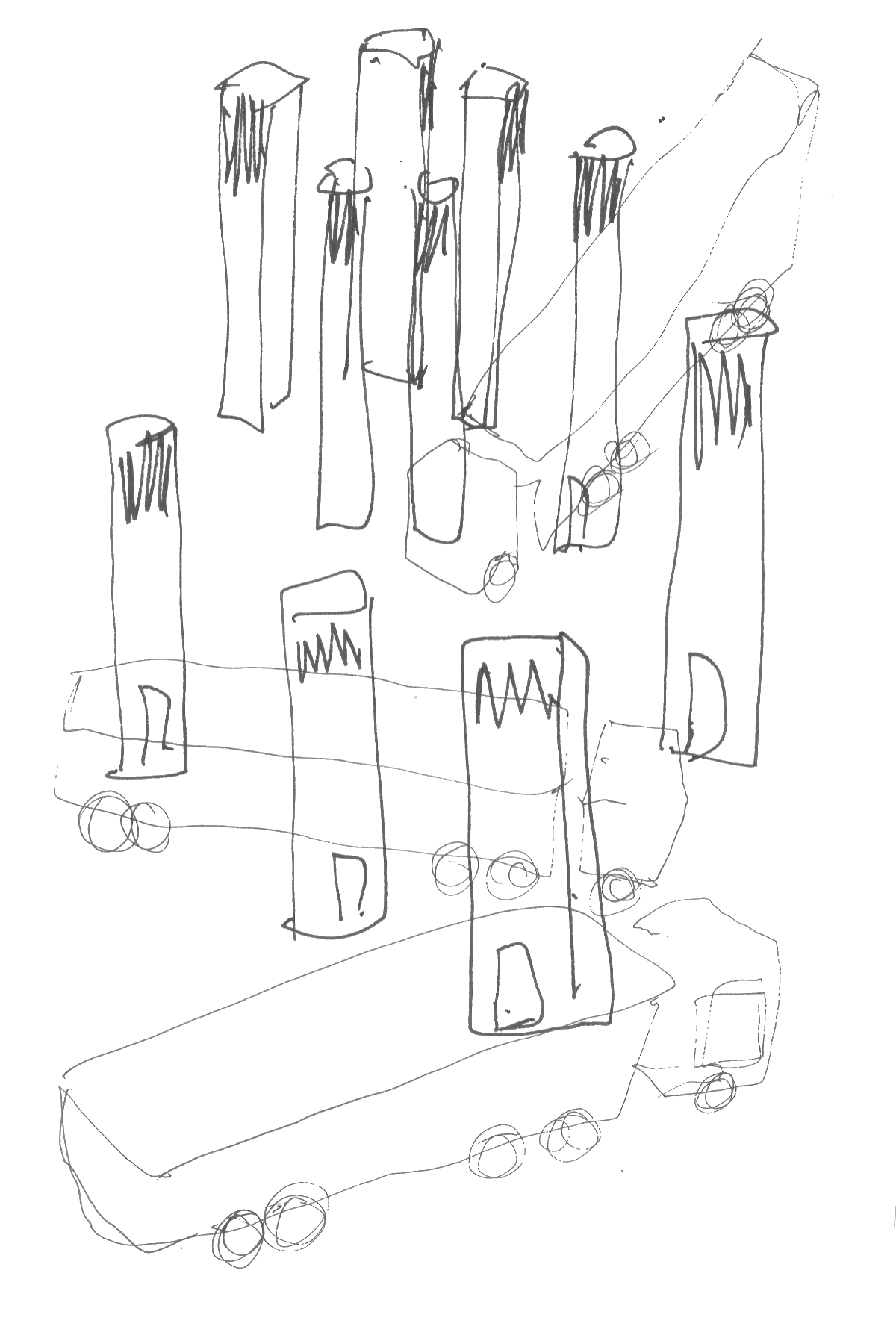

After El Eco, Goeritz continued to experiment with planes and forms of polychromed wood, which led directly to the commission, with Barragan, for the Torres de Satélite in Mexico City in 1957. The towers consist of five triangular polychromed concrete columns on the highway marking the entrance to the Satellite City, a suburb that contains Barragan's Las Arboledas.

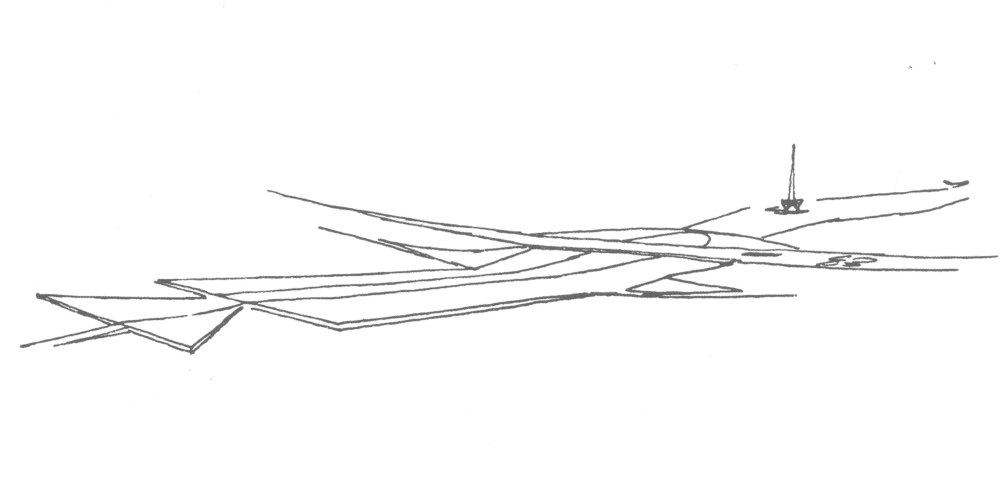

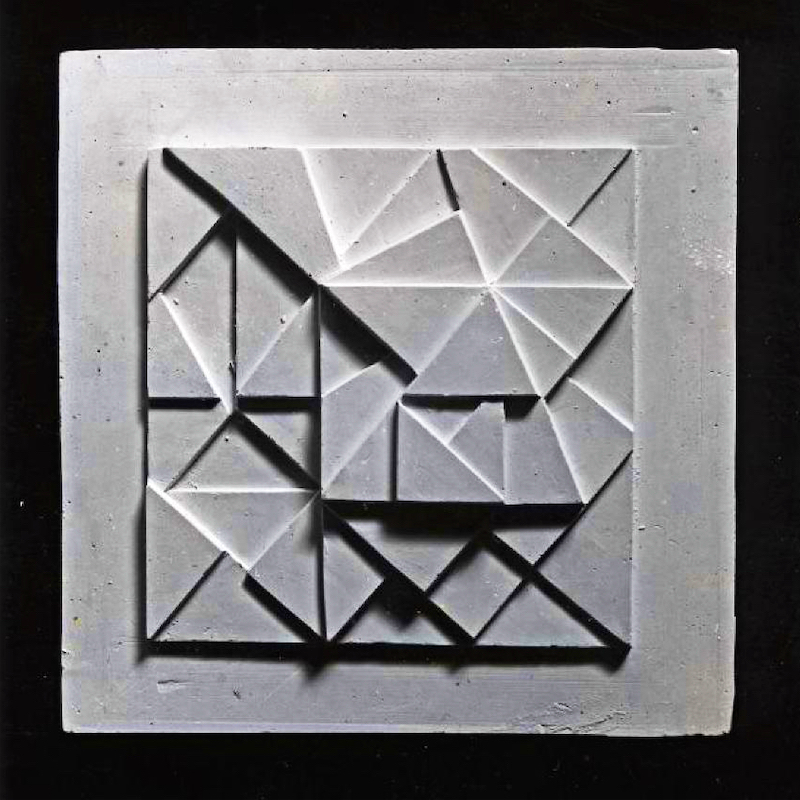

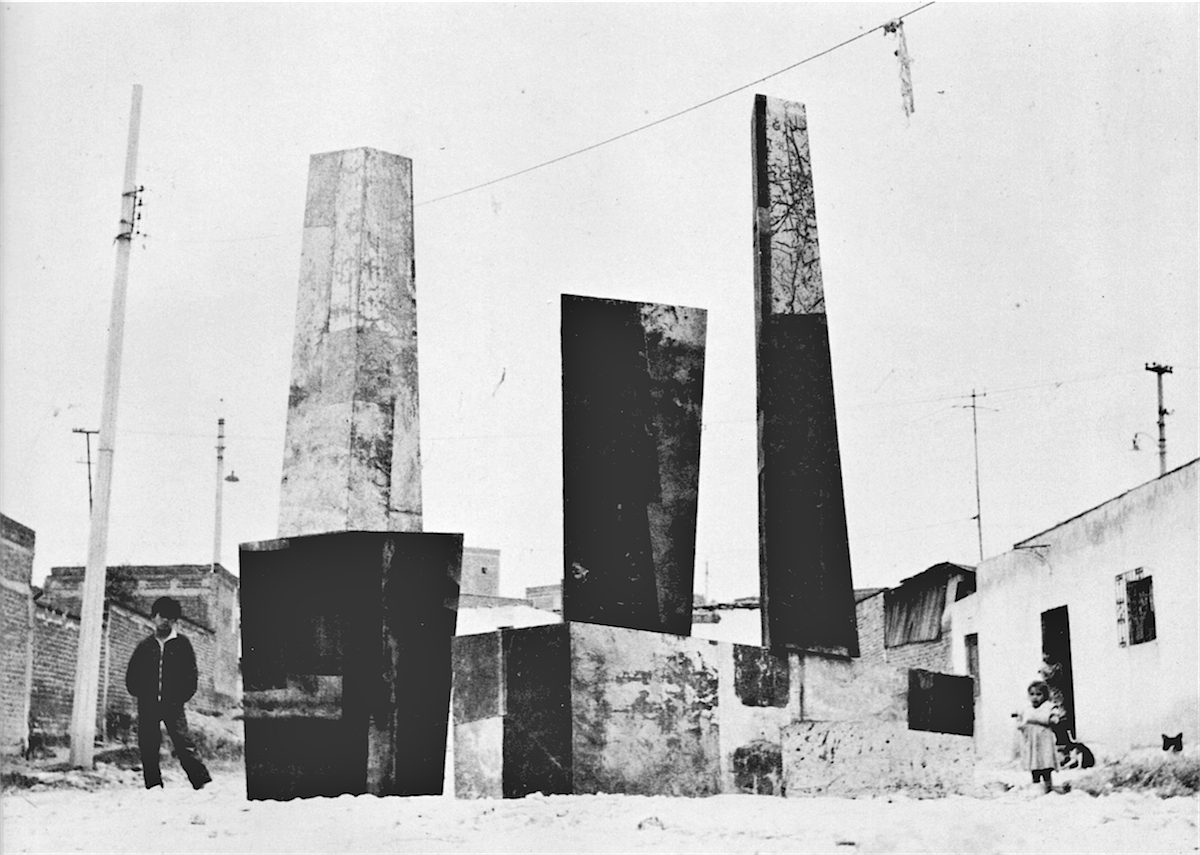

Mathias Goeritz: Realization No. 3, Mexico City 1959

© Clive Bamford Smith: Builders in the Sun. Photo by Marianne Goeritz.

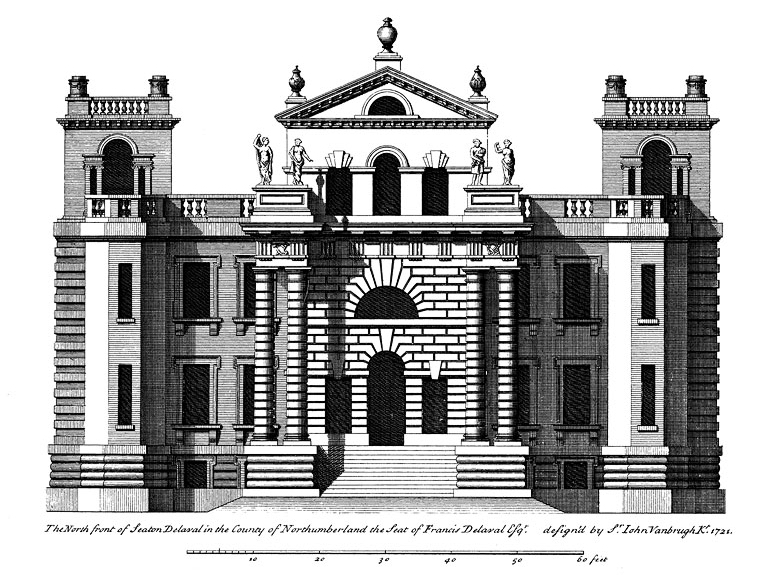

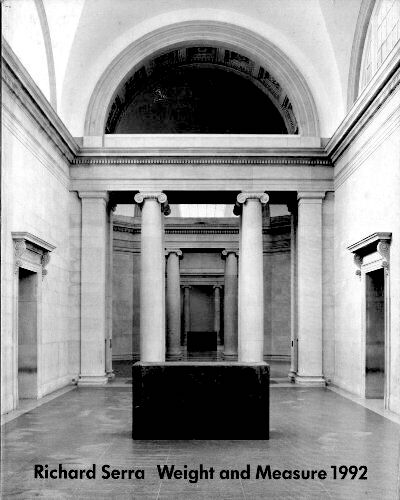

Goeritz took the forms of Emotional Architecture to an urban street in Mexico City as 'Realizations', using polychromed wood and scrap steel sheets, in 1959. I have no evidence whether this work was successful or not, and indeed success is a difficult term to measure in this context, but this was made and installed before abstract sculpture became absorbed into what Robert Hughes (in '

On Art and Money') called the commodification of the art market, so I suspect it was not regarded as an imposition as much later abstract sculpture was. This work was part of a series of

Messages and Realizations that were exhibited at the Carstairs Gallery in New York City in 1960. This was just before the the exhibition 'Primary Structures: Younger American and British Sculptors' at the Jewish Museum in New York City in 1966 and the emergence of artists like Richard Serra in 1968, but I do not know whether Goeritz had any influence on the New York art scene. In any case, influence is the wrong concept: artists and architects collect and reuse their own interests and experience in their work.

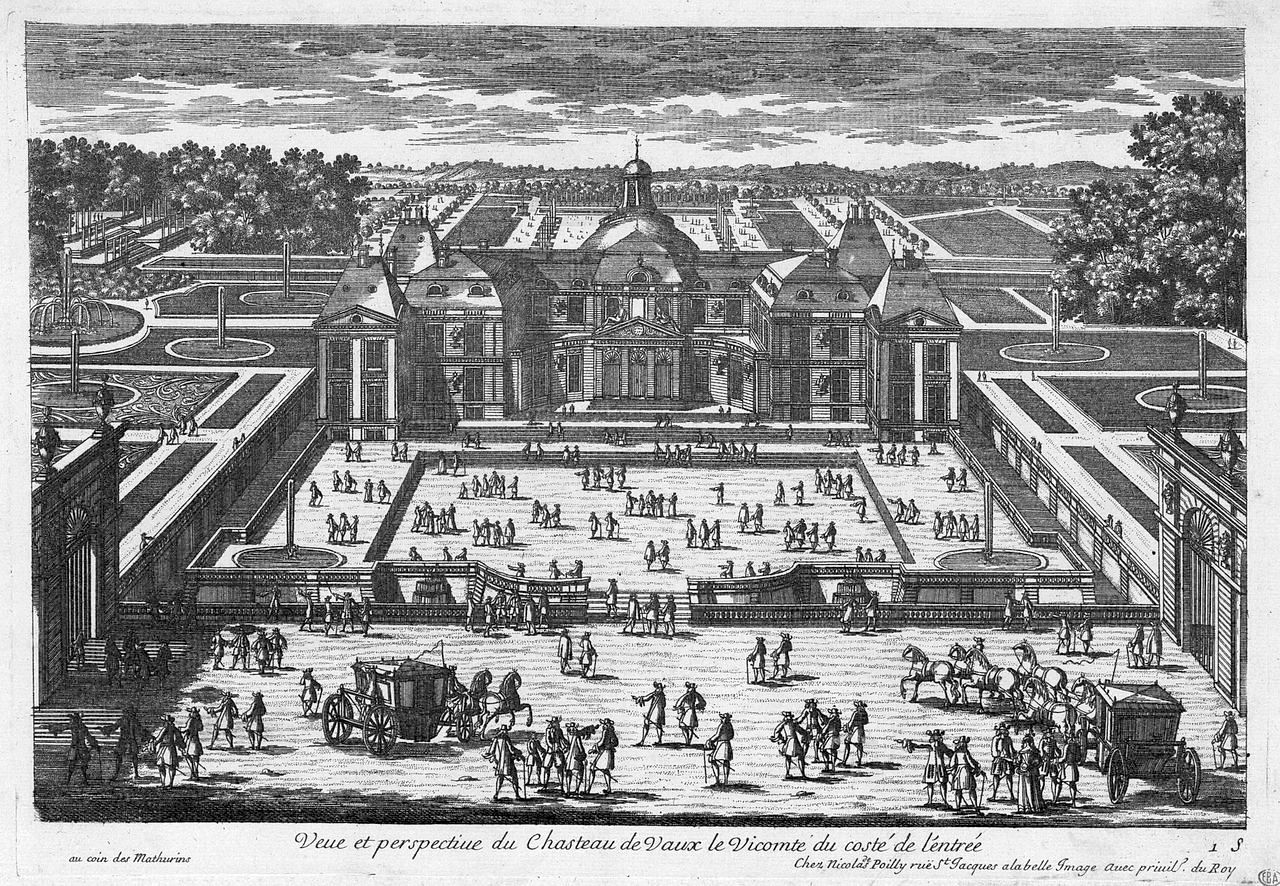

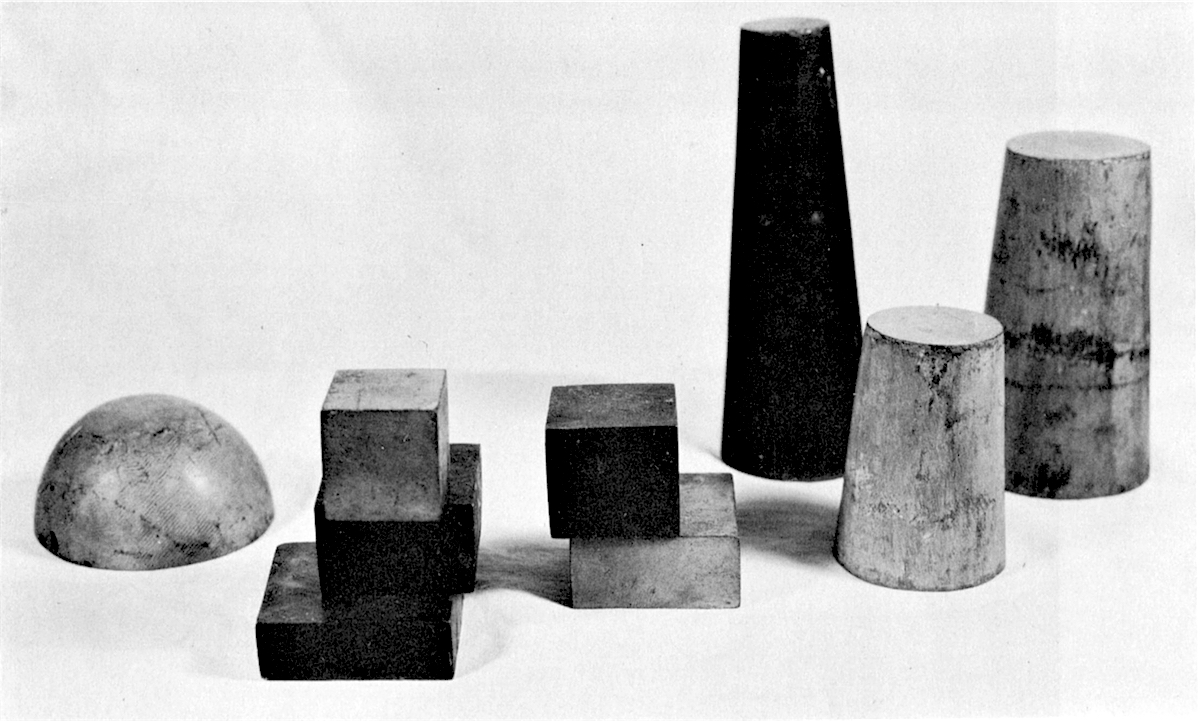

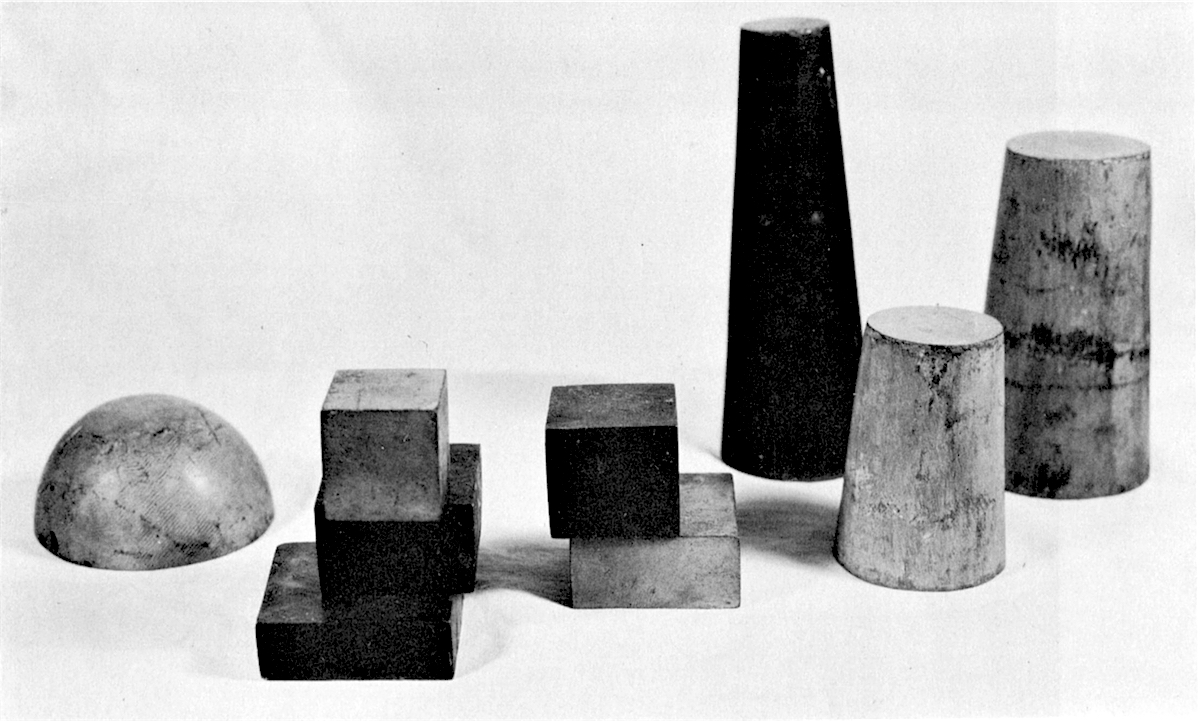

Mathias Goeritz: 'Do it Yourself' Sculpture 1960

© Clive Bamford Smith: Builders in the Sun. Photo by Marianne Goeritz.

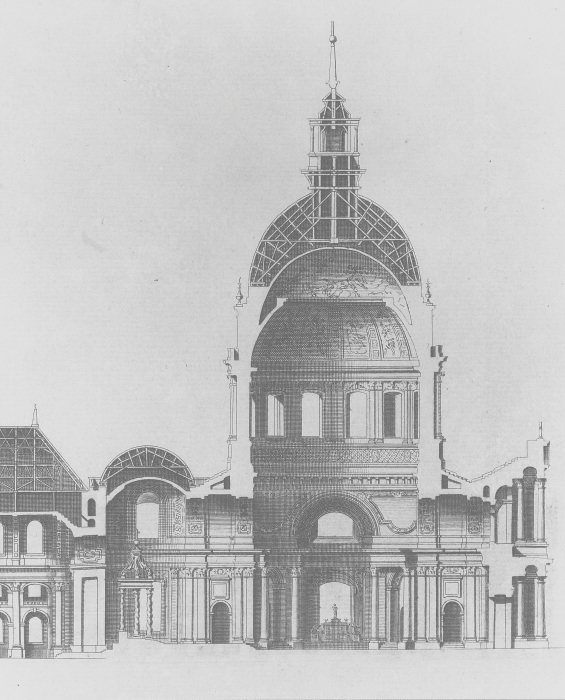

One of my favourite pieces by Goeritz, at the opposite extreme of the social spectrum to the urban street, is the 'Do it Yourself' sculpture, a series of bronzed wooden blocks, truncated cones and a hemisphere that can be arranged in any pattern by the owner. These are not 'Mexican' shapes: they have become identified as Mexican by association with Barragan and Goeritz. 'Do it Yourself' has the same hand-sized tactility of 'Prometheus' by Naum Gabo and 'Torpedo Fish' by Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, and the same way of engaging the aesthetic sensibility as the '

Group of Three Magic Stones' by Barbara Hepworth, in Kettles Yard, Cambridge. The comparison with these great artist is fully justified.

I was pleased to have been able to visit some of

Luis Barragan and Mathias Goeritz's work in Mexico City:

Luis Barragan and Mathias Goeritz: Torres de Satélite, Mexico City, 1957

photo © Thomas Deckker 1997

Thomas Deckker

London 2020