thomas

deckker

architect

critical reflections

The Désert de Retz

2024

2024

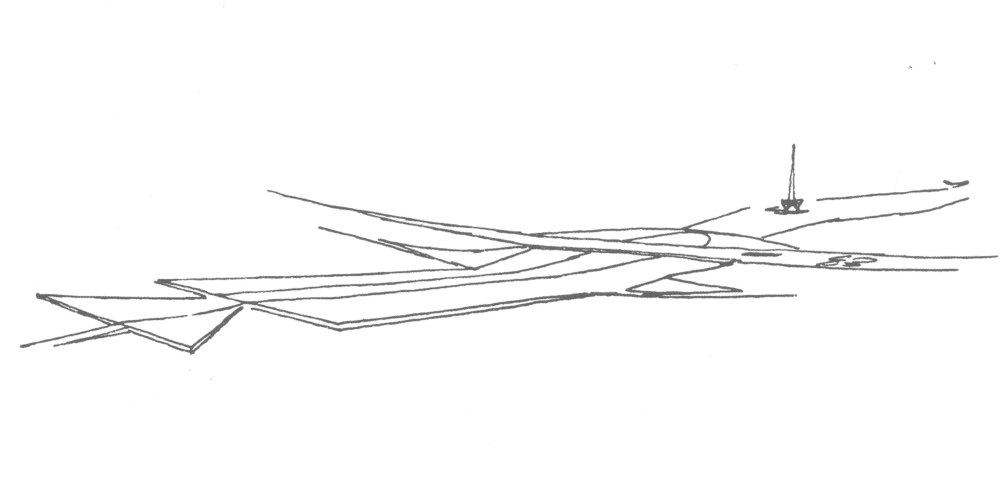

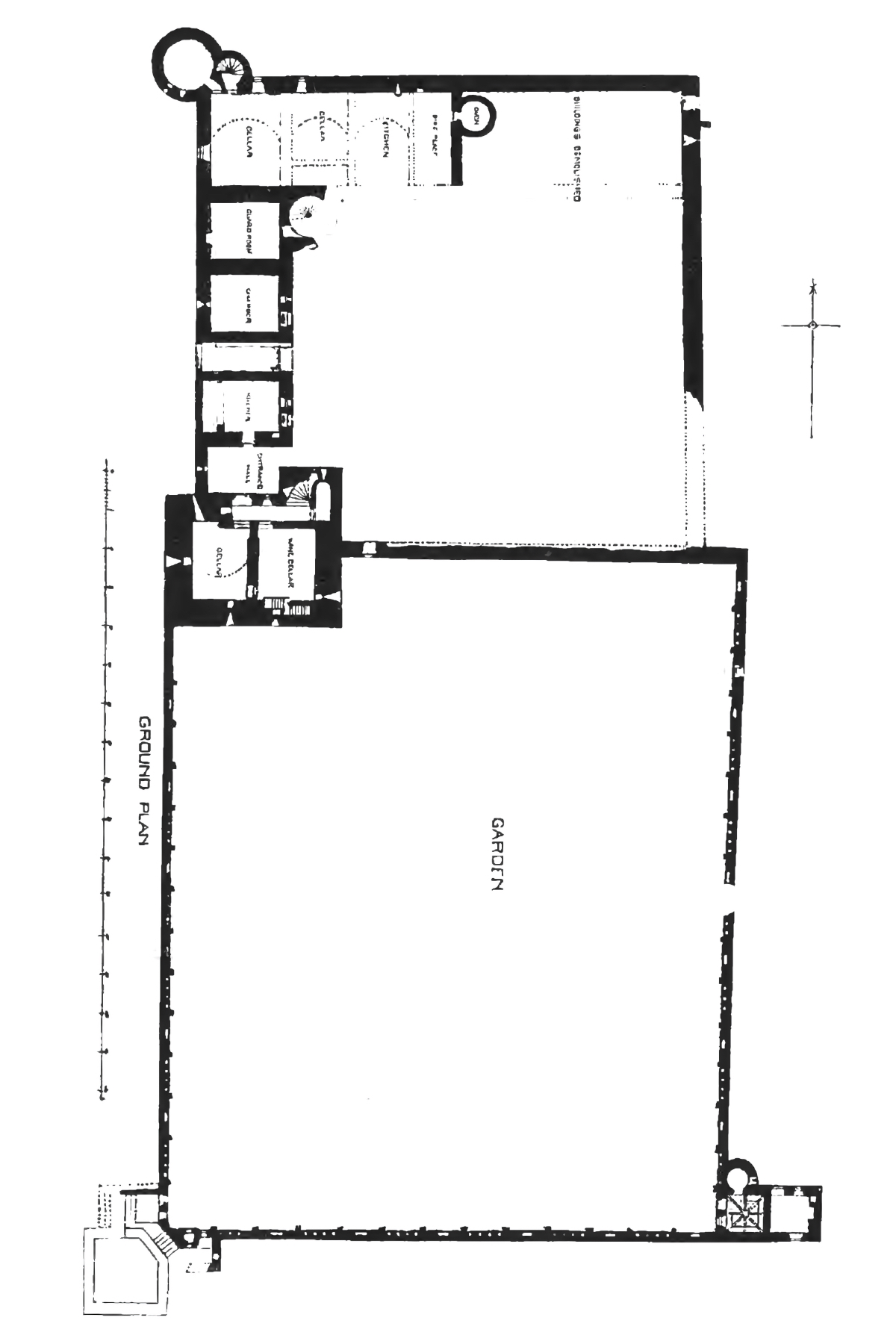

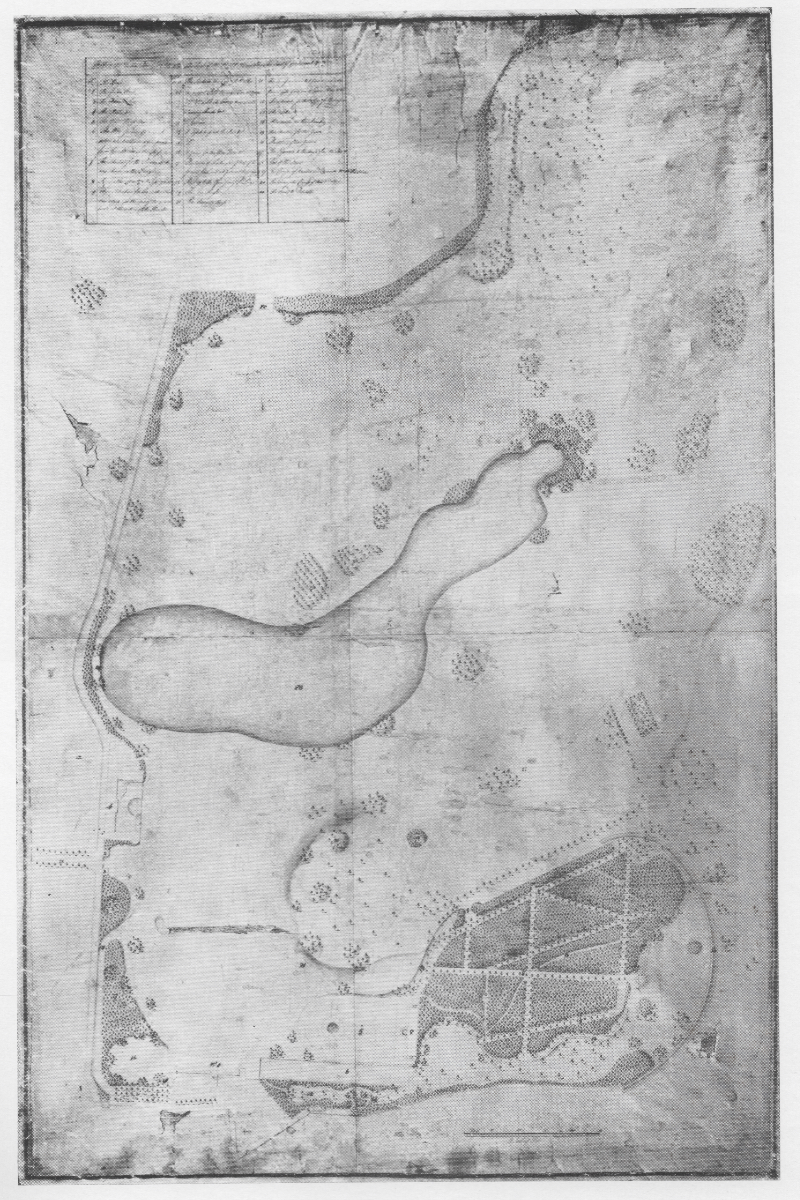

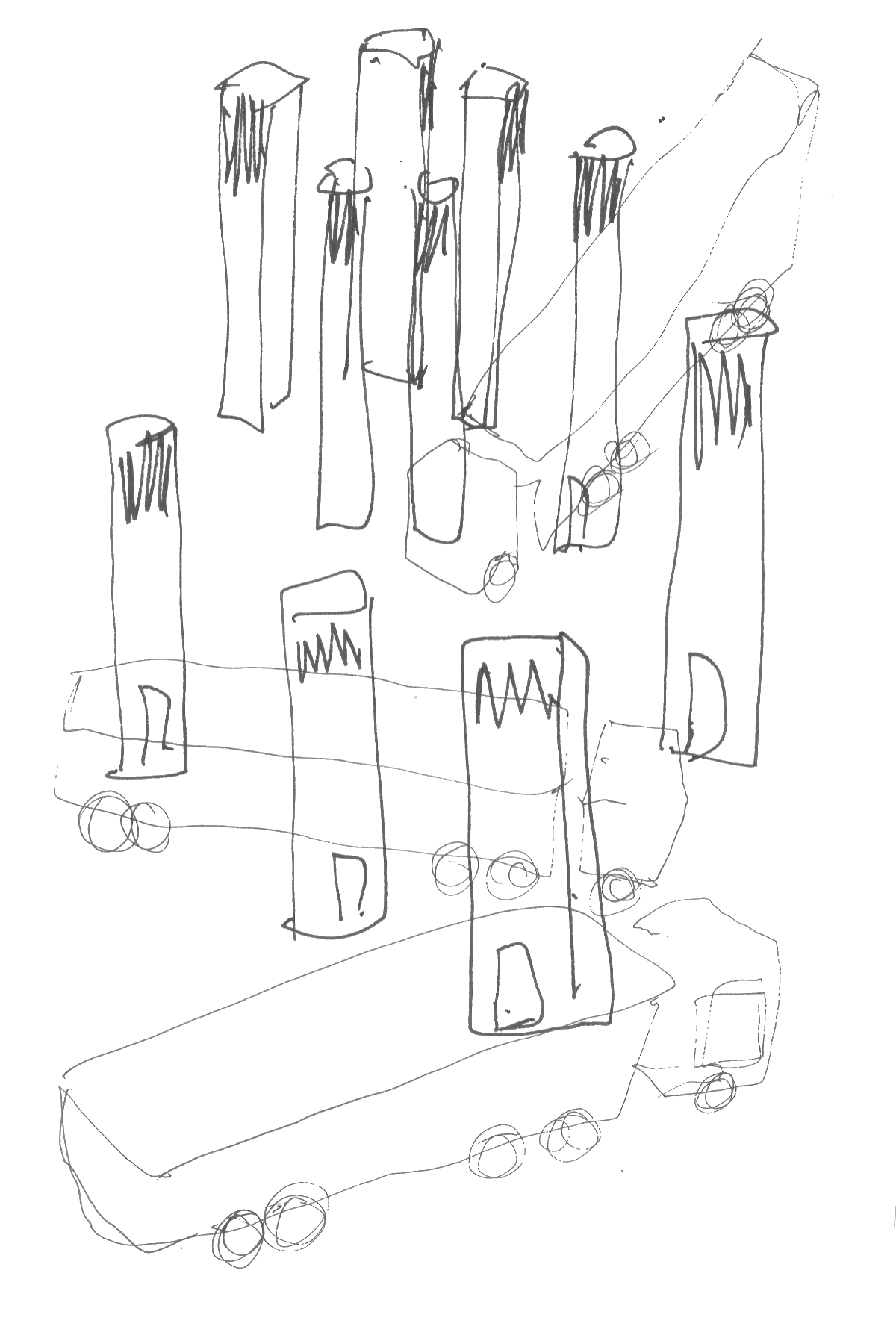

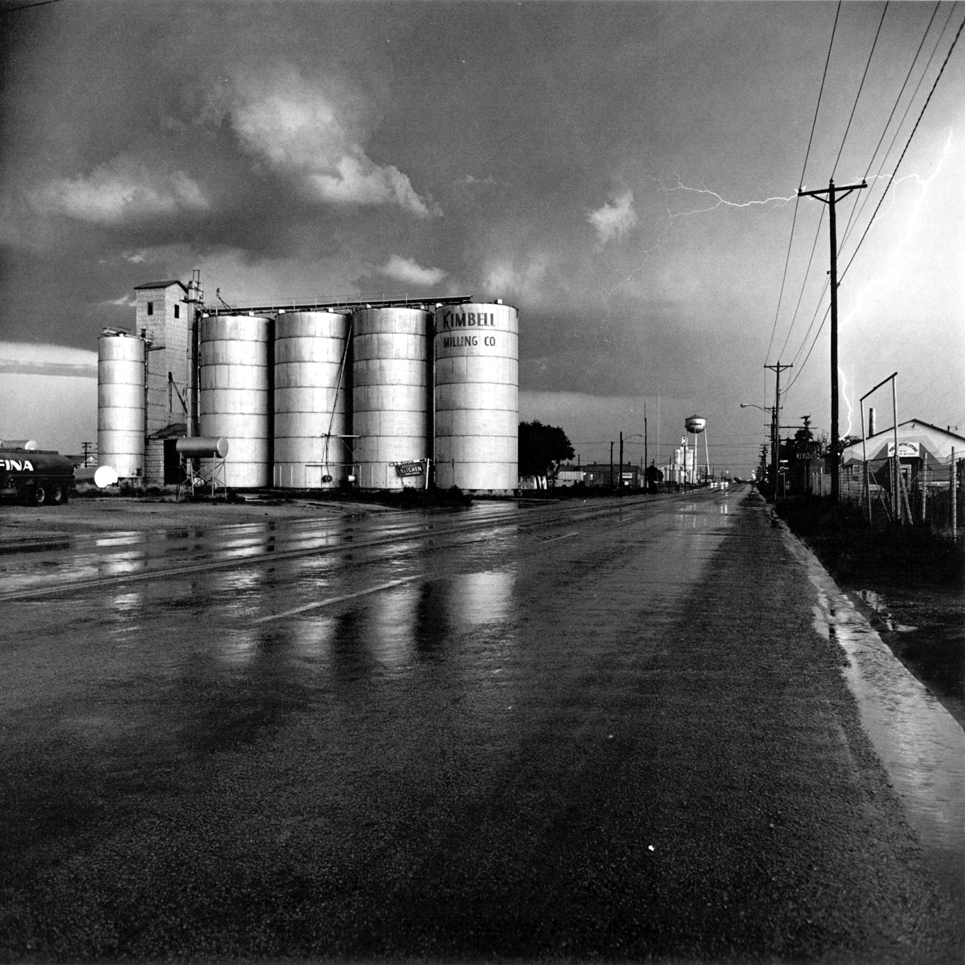

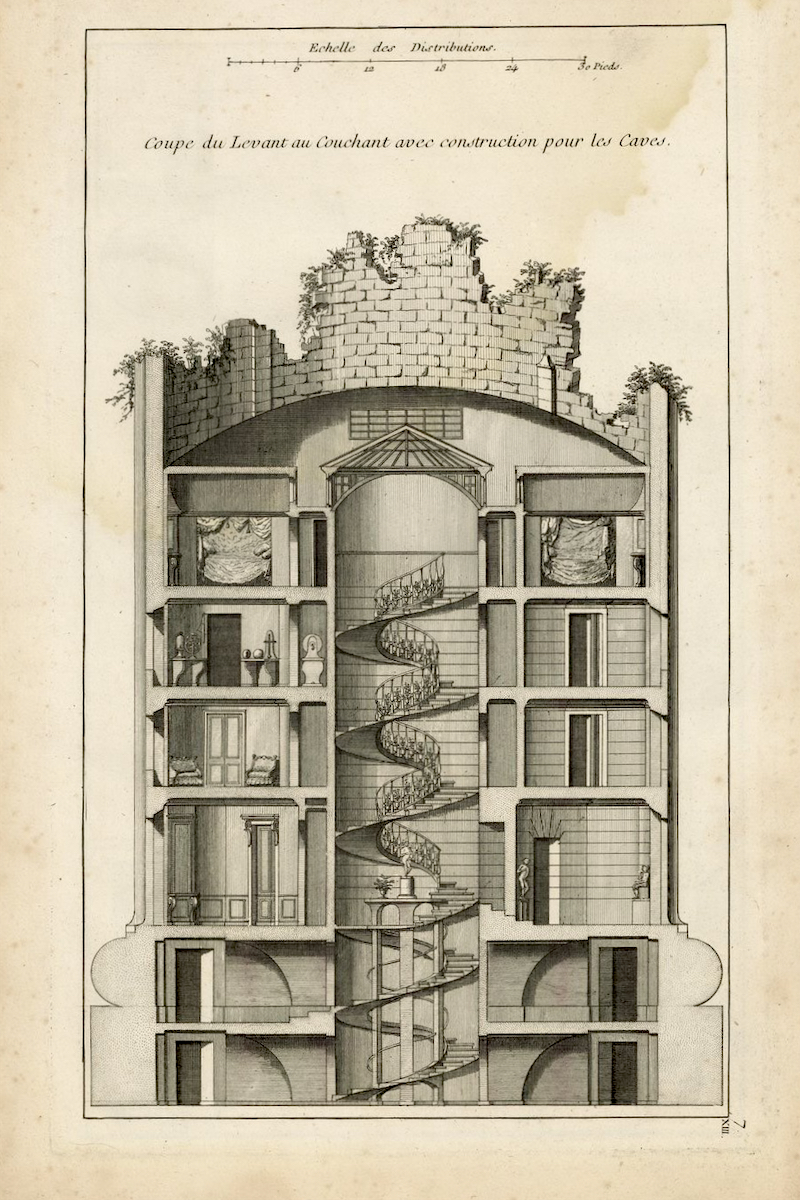

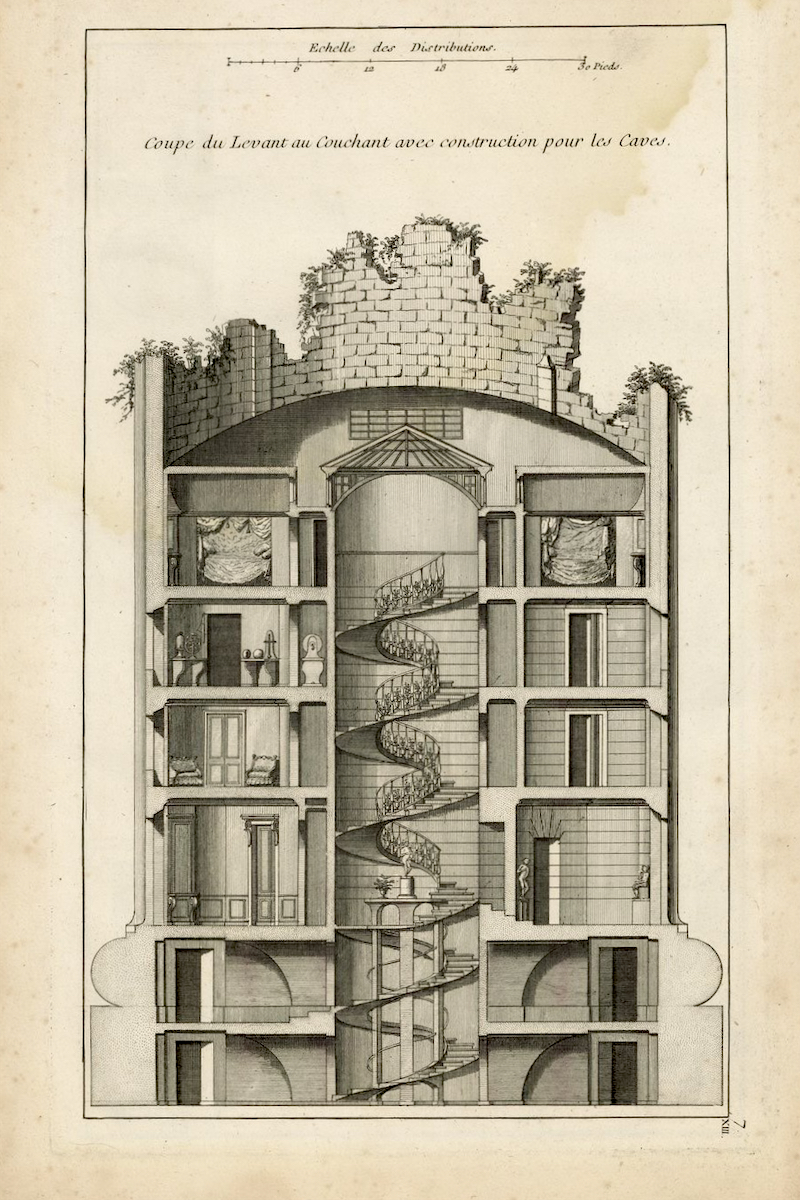

François de Monville: le Colonne Détruite, Désert de Retz (1781-1785)

from François de Monville: Cahier des Jardins Anglo-Chinois (Paris 1785) [1]

from François de Monville: Cahier des Jardins Anglo-Chinois (Paris 1785) [1]

The Désert de Retz

I became fascinated with the Désert de Retz while a student at the Architectural Association School. I visited it long before it was renovated and its centrepiece, the Colonne Détruite, was still a ruin. The Colonne Détruite was actually a ruin of a ruin, as it had been built deliberately as a ruin - a ruined column.

François de Monville: the Colonne Détruite, Désert de Retz (1781-1785)

© Thomas Deckker 1984

© Thomas Deckker 1984

The state of the Colonne Détruite at my visit, as an agricultural store. Incredibly it was a family home until 1949.

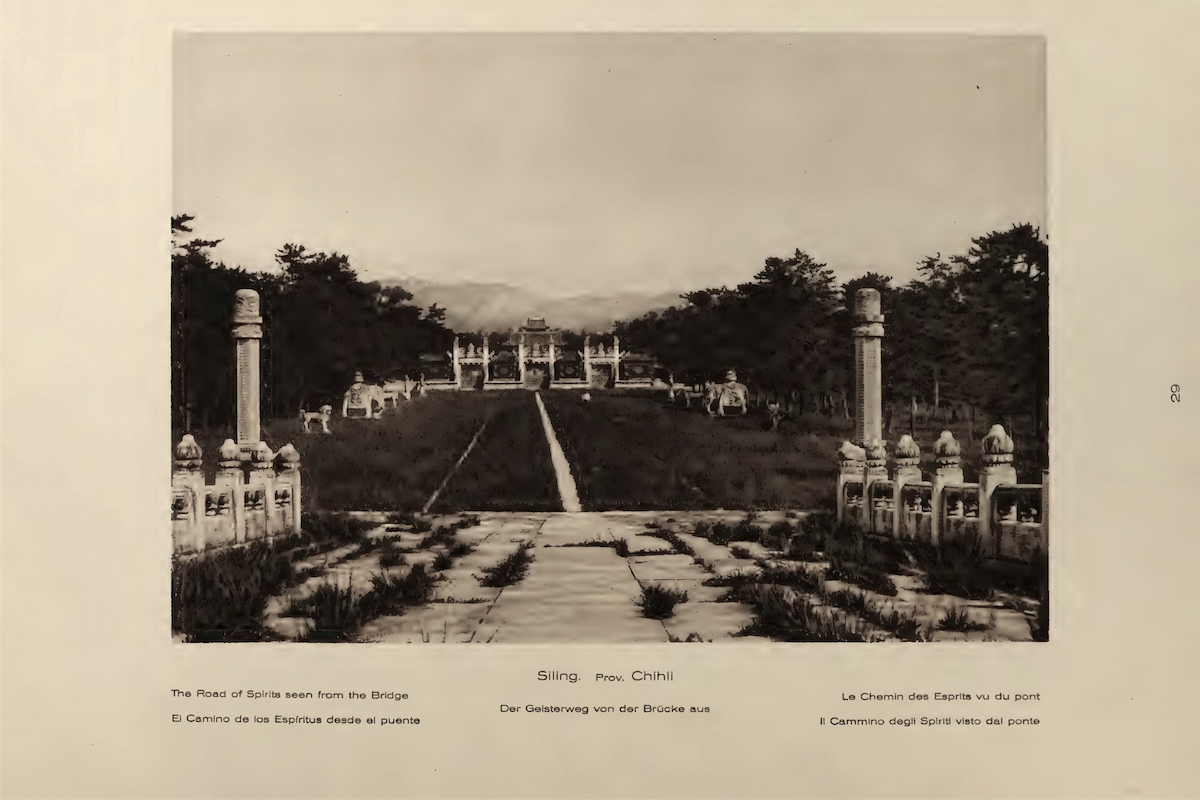

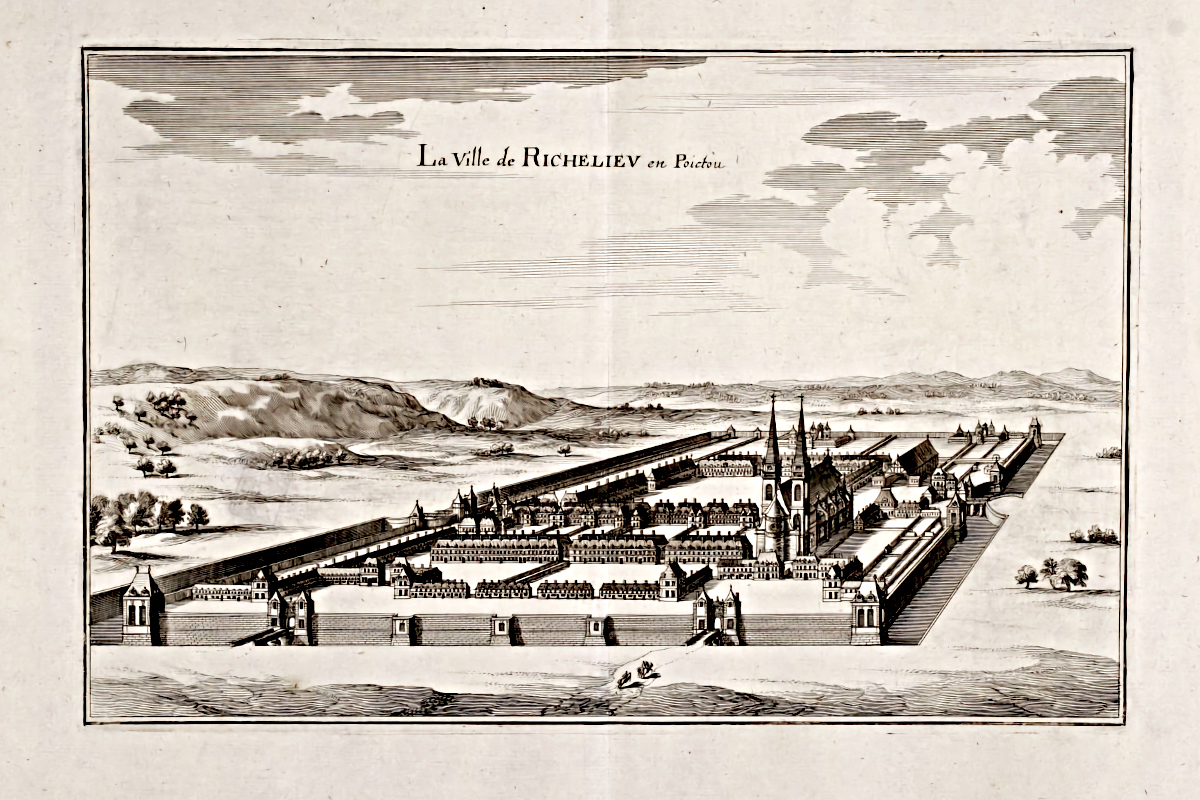

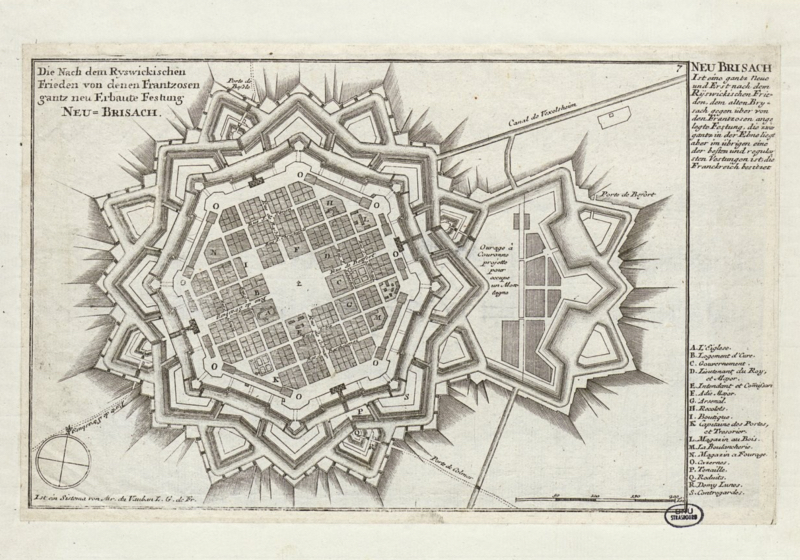

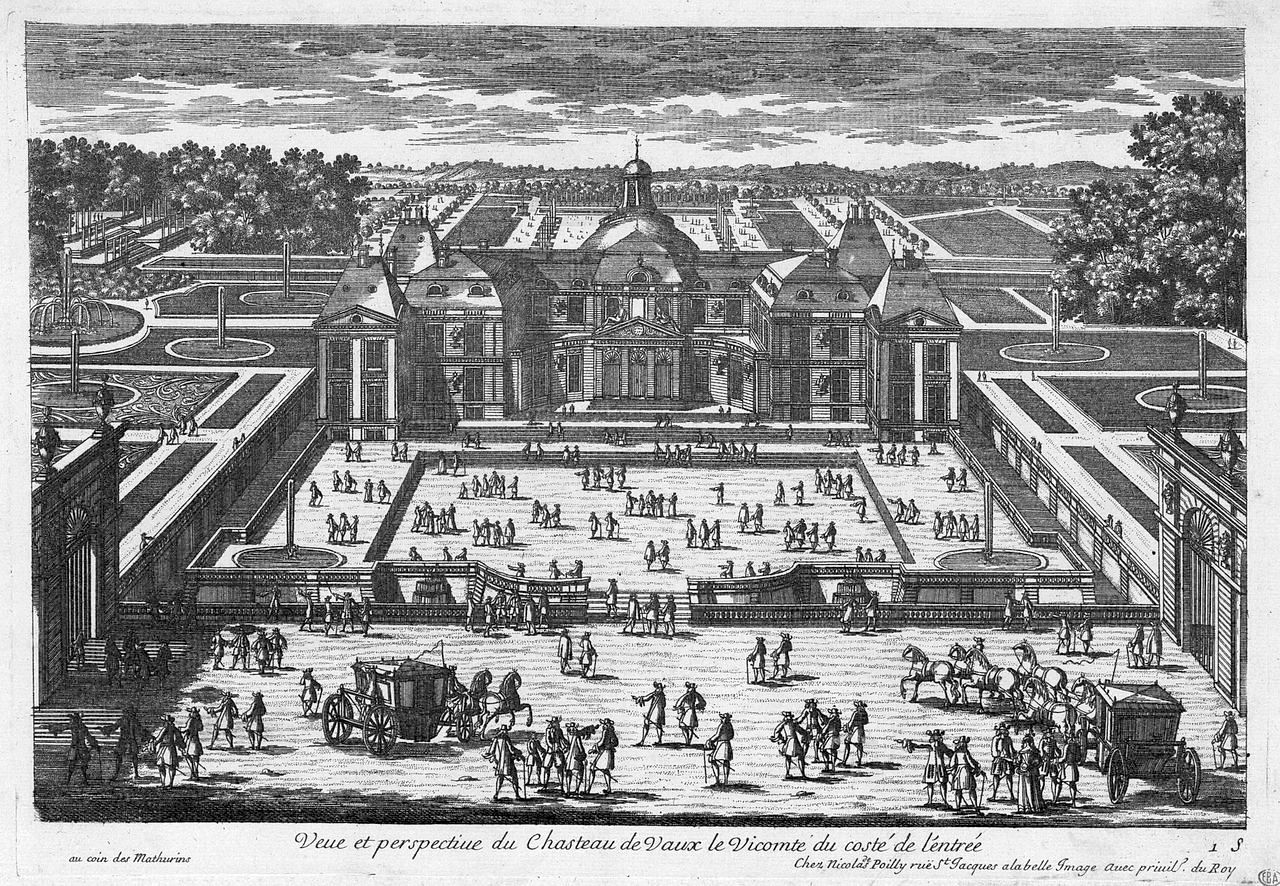

The Désert de Retz was built between 1781-85 by François de Monville as a landscape of pavilions, to be a country retreat outside Paris. This form of landscape garden originated in England in the 18th century, exemplified in gardens such as Stourhead (c. 1740-80) for the banker Henry Hoare, or Petworth (c. 1751-63) for the Earl of Egremont. In their archetypal form these gardens were intended to represent and recreate a mythical classical past, or Arcadia, by mixing 'natural' landscape with pavilions derived from Roman temples. These were idealised in the paintings of Claude (whose 'Landscape with Aeneas at Delos' Henry Hoare owned). While Stourhead was Arcadian, evoking a purely classical past, the Désert de Retz was more exotic and contained pavilions in a variety of architectural styles. This exoticism was not unknown in England - William Chambers built a 'pagoda' at Kew Gardens - but was much more popular in Europe where it was generally called (in French) 'Anglo-Chinois". [2]

Henry Flitcroft: Temple of Apollo, Stourhead, seen across the lake

© Thomas Deckker 2013

© Thomas Deckker 2013

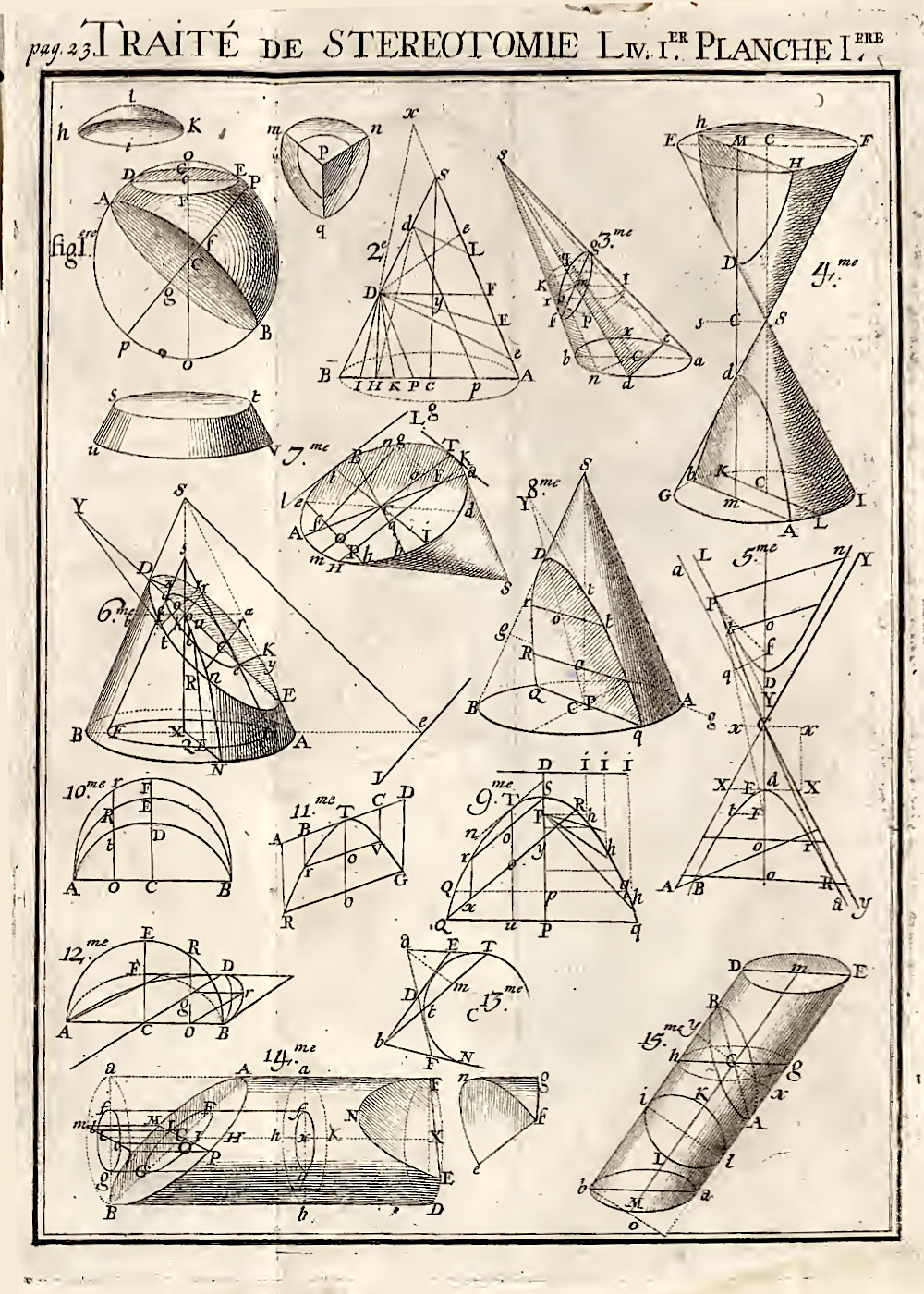

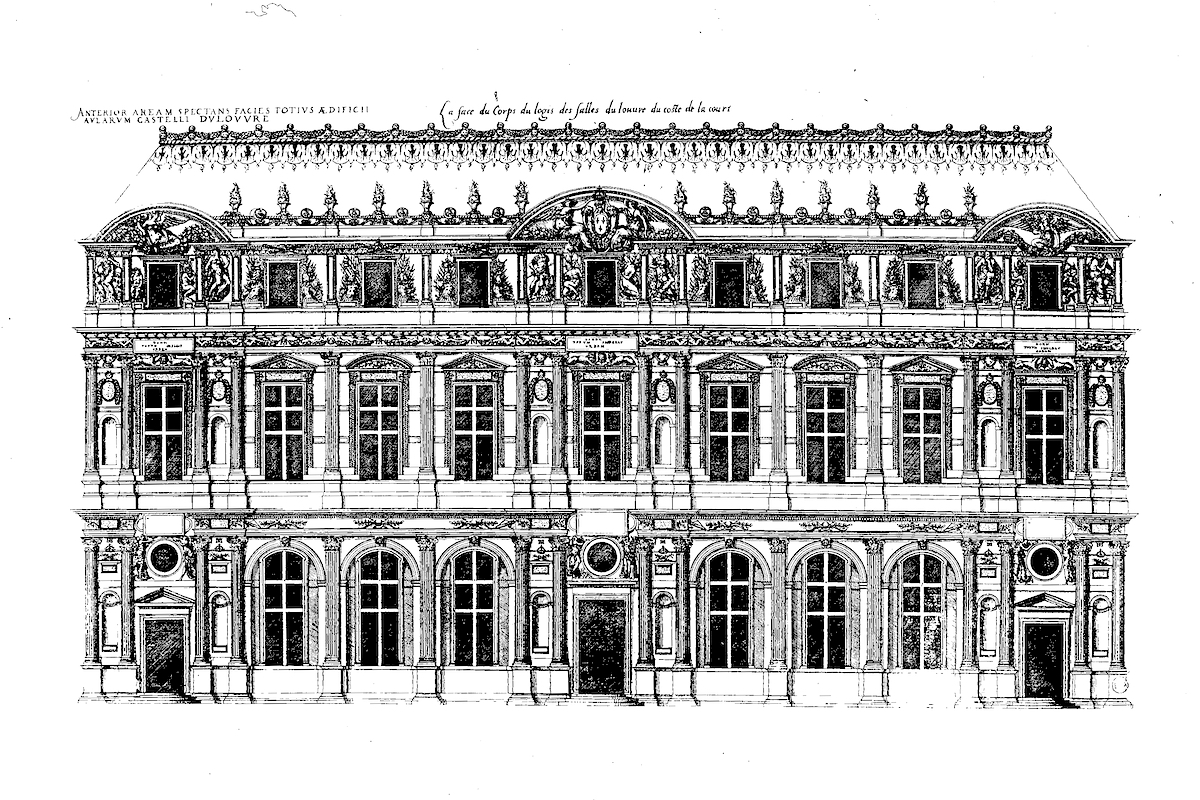

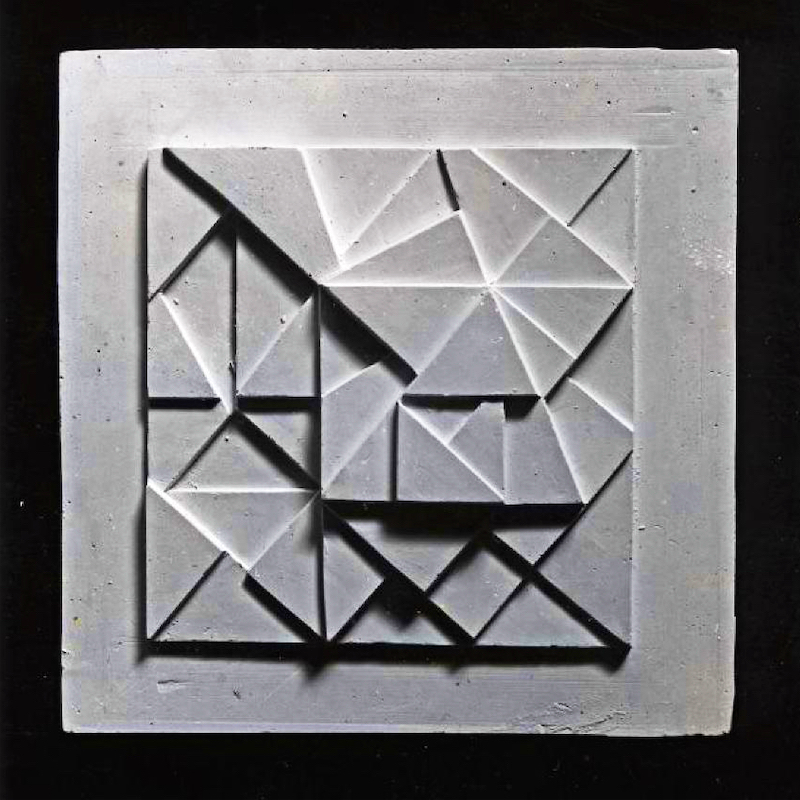

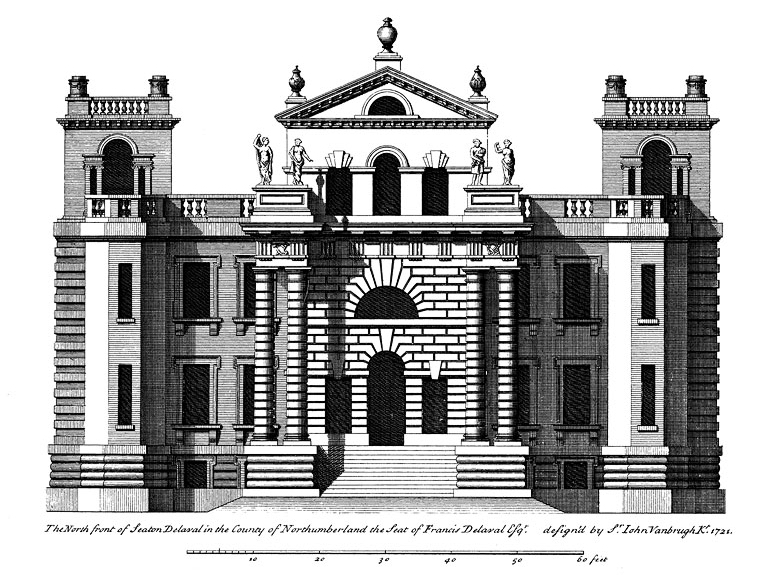

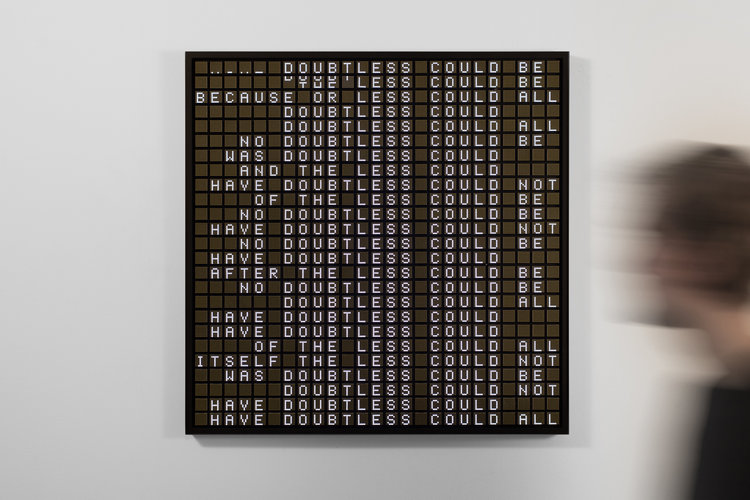

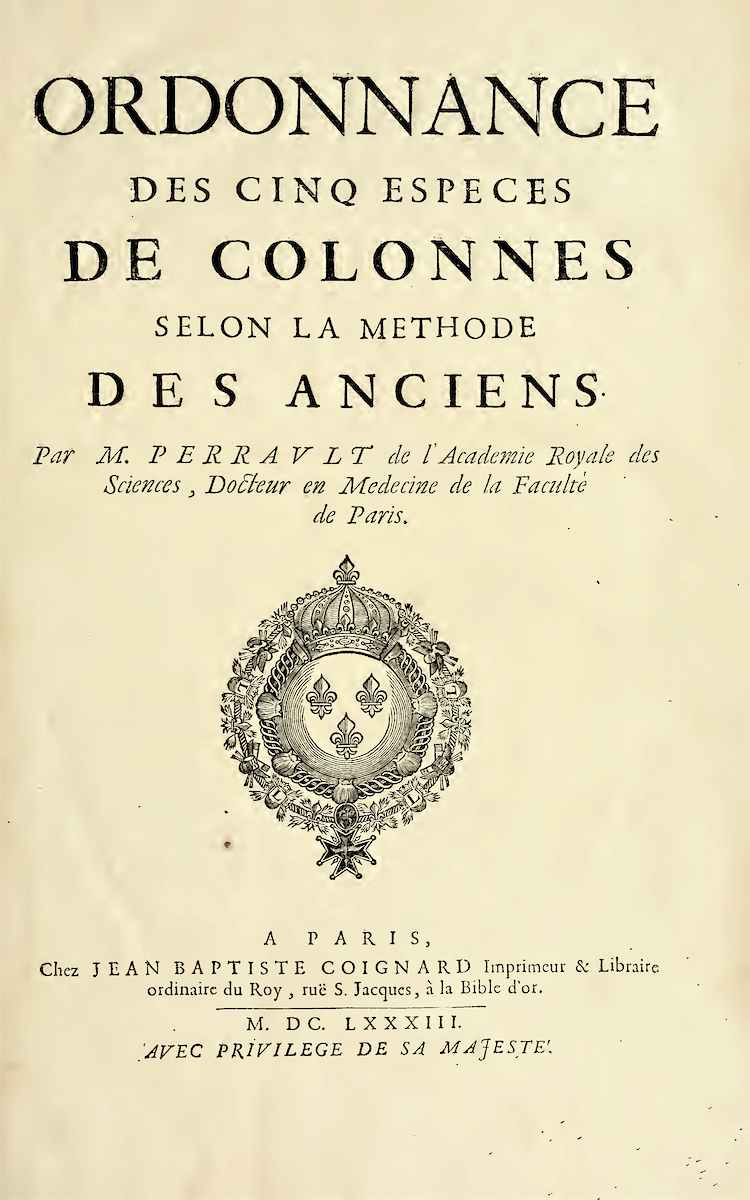

There were 2 reasons that the Colonne Détruite may have been seen as transgressing architectural boundaries. The first was that de Monville was actually living in a garden pavilion, rather than looking at it from the window of his house. The other was that the correct use of the Roman orders codified by Vitruvius in De architectura was central to how architects and patrons conceived of the art and science of architecture (it was not yet a profession) during the Renaissance and Enlightenment, in particular of the design of public buildings. While the orders themselves were subject to the strictest governance, how they were used and combined was very flexible: art history has identified various theories and practices such as High Renaissance, Mannerism, Baroque and Neo-Classicism in these periods. Claude Perrault, one of the leading figures of the French Enlightenment, translated Vitruvius into French and wrote a treatise on the correct design of columns. [3] He strongly supported a more flexible and elegant use of the orders, however, rather than remaining faithful to Vitruvius, in the 'quarrel of the ancients and moderns' among architectural theorists in mid-seventeenth century France. For the celebrated East Front of the Louvre (1667-74), he used paired fluted Corinthian columns on the East Front, which became a model for French architecture until the French Revolution.

Claude Perrault: Ordonnance des cinq especes de colonnes selon la methode des anciens (Paris 1683)

Plate III. The plate shows a fluted column of the Doric Order similar to the lower part of the Colonne Détruite.

Plate III. The plate shows a fluted column of the Doric Order similar to the lower part of the Colonne Détruite.

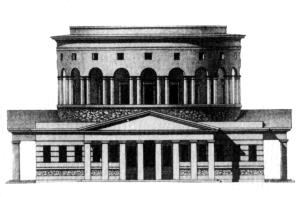

De Monville was certainly interested in architecture: he had a least one hôtel particulier (private mansion) in Paris designed by the architect Étienne-Louis Boullée, best known for his visionary schemes of sublime architecture. Boullée's only remaining Parisian hôtel, the Hôtel Alexandre, while certainly not as sublime as his visionary schemes, shows a tendency to break the rules of composition regarded as epitomising French aesthetic superiority. The giant order at the entrance supports not a temple front but a recess, surmounted not by a pediment but by an entablature.

Eugène Atget: the former Hôtel Alexandre (1763-66) by Étienne-Louis Boullée

Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

It is tempting to see the Colonne Détruite as prefiguring the French Revolution, when both the orders of classical architecture and divinely-ordained monarchy were overturned. Although a prominent figure of the Enlightenment, and possibly a Freemason, it is unlikely that de Monville attributed the significance that may be given to it in hindsight. Thomas Jefferson, United States ambassador to France at the time and future president, is known to have visited the Désert de Retz with his mistress Sally Hemings. Roman architecture was considered, in the United States, as representing Republican virtues rather than the Monarchy it was associated with in France. The oft-repeated claim that the garden design represents a Masonic initiation ceremony, if at all true, is likely to be little more than an interesting narrative drafted in to supplement the main ambition of a rural idyll in much the same way as the narrative of Aeneas visiting the underworld was drafted on to Stourhead.

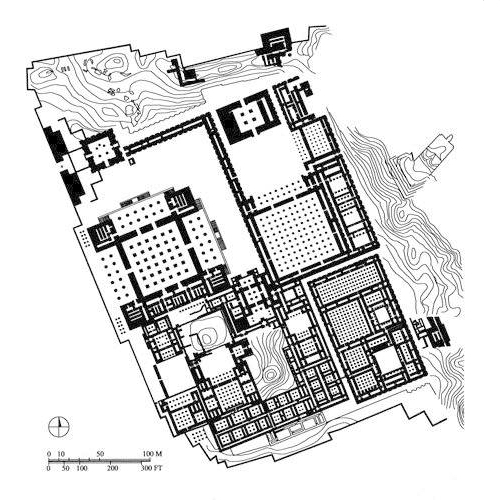

François de Monville: the Désert de Retz (1781-1785)

© Thomas Deckker 1984

© Thomas Deckker 1984

Views from the entrance of the Désert de Retz to the column, and the base of the column. The original entrance was in the present location.

The base was completely hidden by undergrowth. At the time of my visit there was speculation that the entrance to the column was through a tunnel from the base, as part of a Masonic rite, but no evidence has emerged of this.

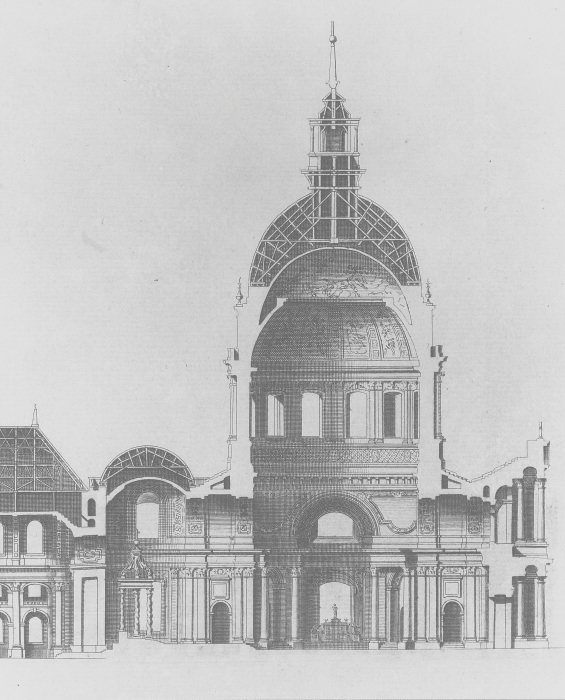

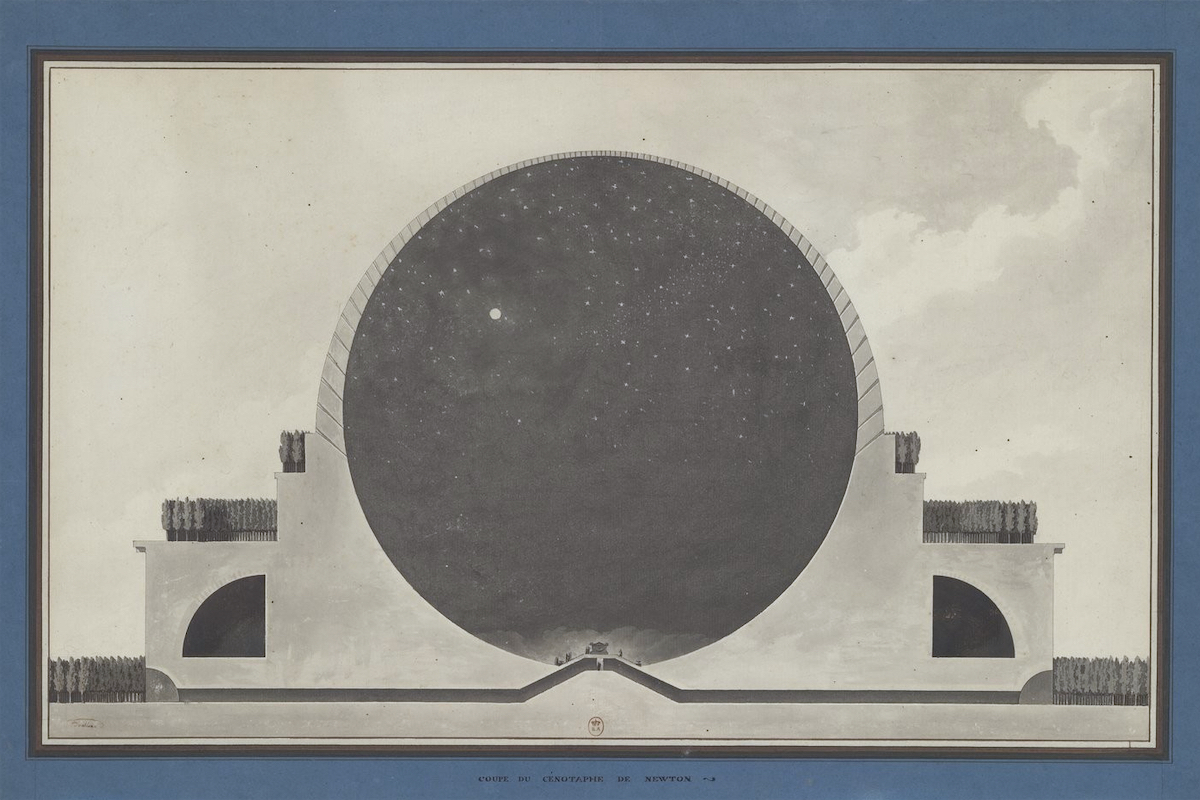

Etienne-Louis Boullée: Cenotaph for Newton (1784)

Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

Note the entrance through a tunnel into the centre of the sphere.

The very conventional entrance is a sure sign of an amateur architect. The form of the column, on a change in ground level exposing the base, has the potential for a very dramatic and unusual entrance.

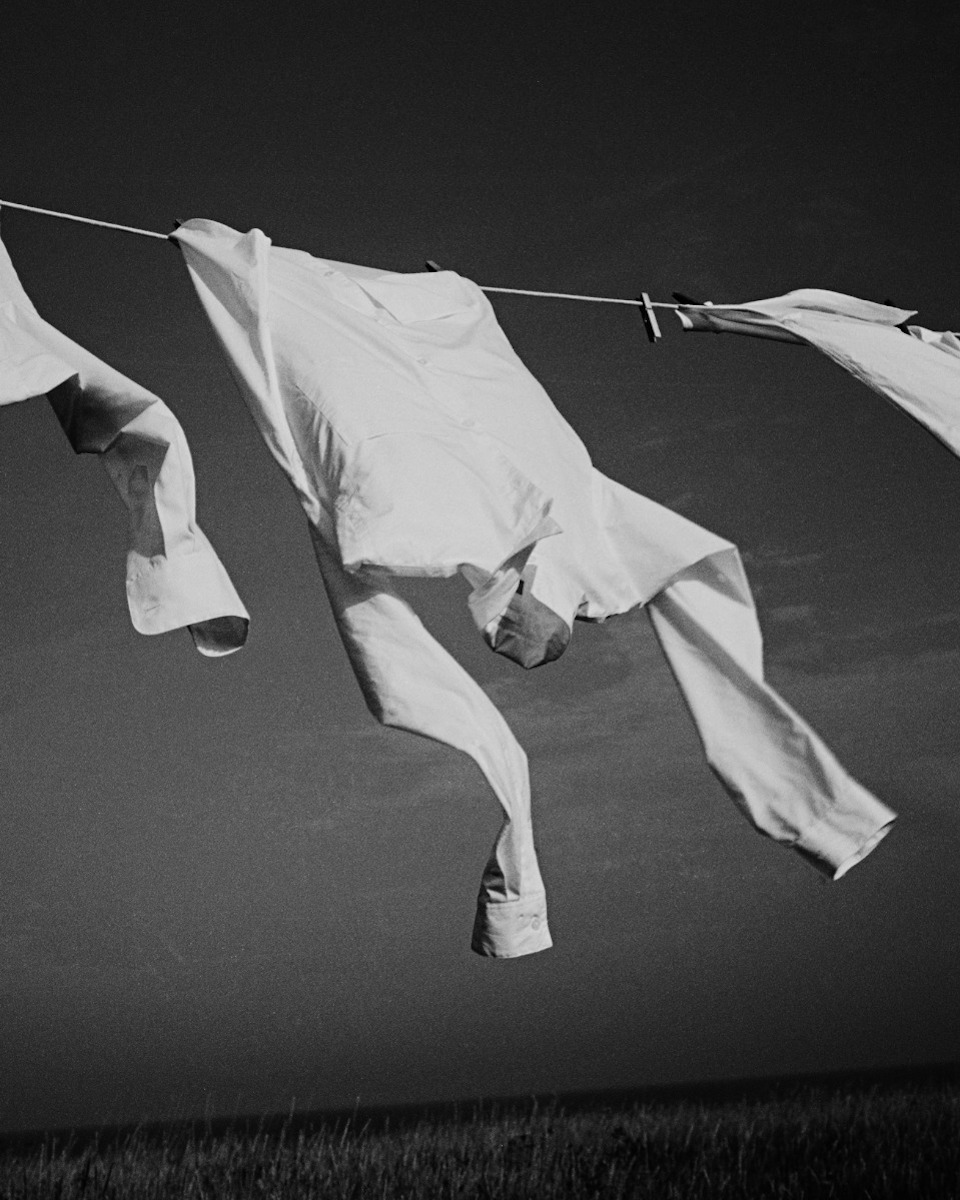

François de Monville: the Désert de Retz (1781-1785)

© Thomas Deckker 1984

© Thomas Deckker 1984

Little remained of the original interior.

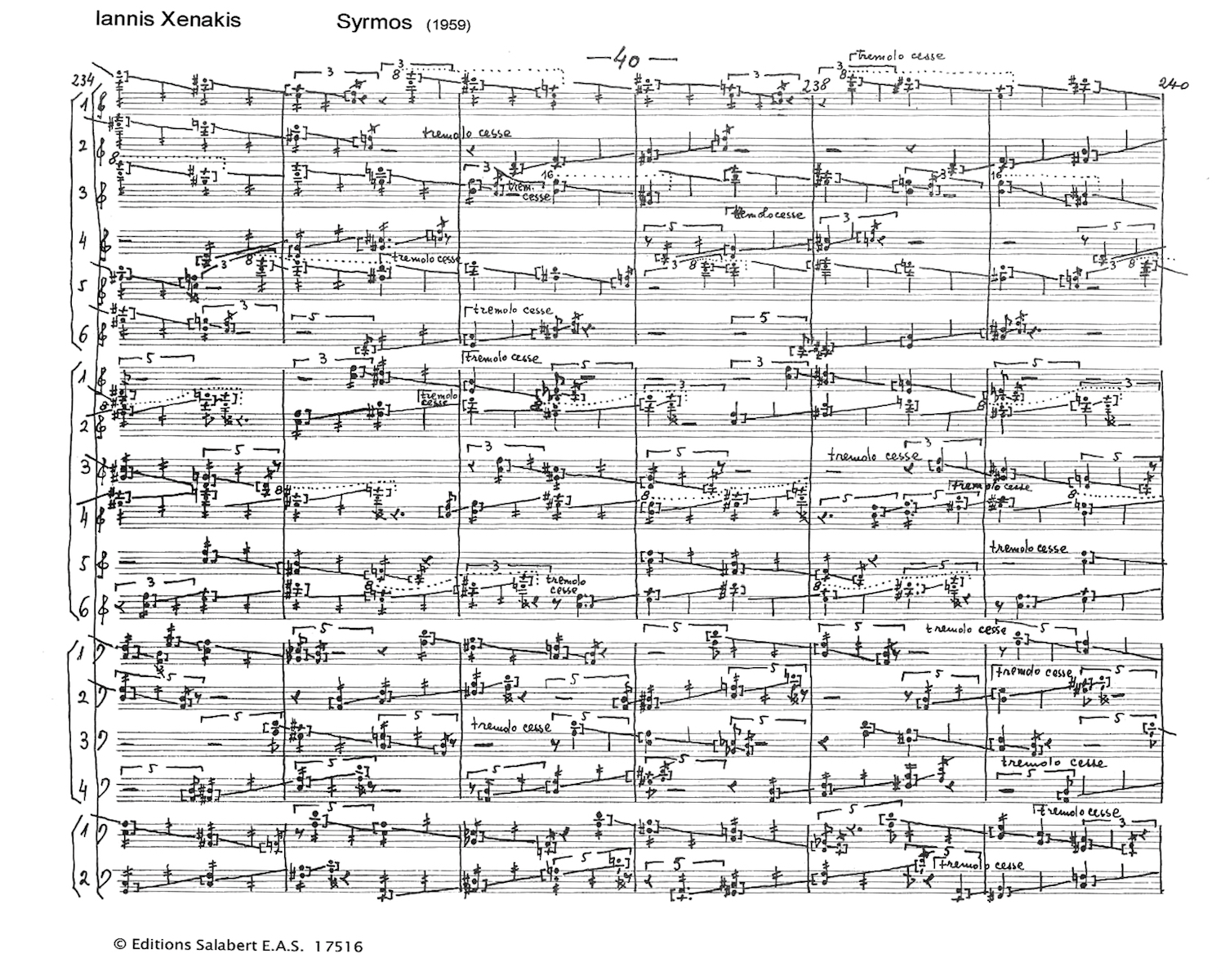

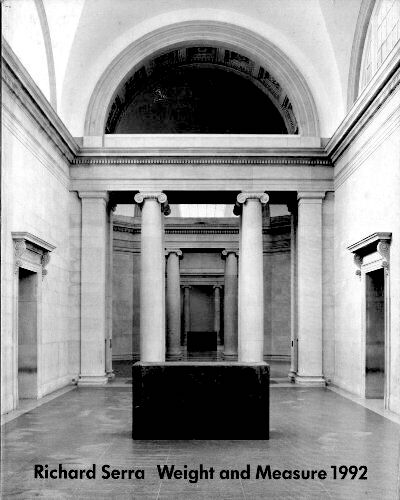

Despite the transgression of setting up a house in a broken column, de Monville's influence on architecture was negligible. The now largely forgotten architectural theorist Antoine-Chrysostome Quatremère de Quincy, a strong advocate of neo-classicism, clearly understood the Colonne Détruite as a folly, or an ornamental building of no practical purpose, and private, while he saw Ledoux's barrières as bizarre, or the perversion of the rules of architecture, and very public. There was outrage among architectural theorists at the time at Ledoux's use of square columns, paired columns supporting an arcade in the drum, and a drum without a dome. The orders did in fact lose their central positon in architectural discourse. The architect Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand, pupil of Durand before the French Revolution and Professor of Architecture at the École Polytechnique after, made the column not a representative device but a structural and spatial armature for large open-plan spaces reminiscent of the new building type of the factory. Labrouste's Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève was entirely without exterior columns. This change in theory and practice can be seen as an architectural equivalent to what Thomas Kuhn called a 'paradigmatic shift' in the history of science, that is from one relatively stable set of beliefs on, for example, building types, construction, aesthetic goals, to another. [4]

Claude-Nicolas Ledoux: Barrière St Martin, Paris (1785-1790)

© Thomas Deckker 1984

© Thomas Deckker 1984

The barrières of the city of Paris, a wall and customs posts, were one of the immediate causes of the French Revolution. They were sacked and burned in 1789, 4 days before the fall of the Bastille.

The Désert de Retz has been beautifully, if partially, restored and is now the property of the commune de Chambourcy. The tranformation is remarkable and the condition when I visited is unrecognisable.

If one finds oneself in Chambourcy a visit would make a pleasant outing. The nearest railway station is Poissy, so it could be combined with a visit to Le Corbusier's Villa Savoye, another Arcadian pavilion. The Désert de Retz belongs to the vanishingly small group of buildings by amateur architects worth visiting for their architectural merit. It is a place of fantasy and dreams, worth appreciating in any form and condition.

If one finds oneself in Chambourcy a visit would make a pleasant outing. The nearest railway station is Poissy, so it could be combined with a visit to Le Corbusier's Villa Savoye, another Arcadian pavilion. The Désert de Retz belongs to the vanishingly small group of buildings by amateur architects worth visiting for their architectural merit. It is a place of fantasy and dreams, worth appreciating in any form and condition.

Footnotes

1. These plates were also published in Jardins Anglo-Chinois by Georges Louis Le Rouge (Paris 1770-87) ↩

2. Gustav III, King of Sweden, visited the Désert de Retz and made a copy of Monville's 'Tartar tent' at Drottningholm. ↩

3. Claude Perrault: Ordonnance des cinq especes de colonnes selon la methode des anciens Paris, J.B. Coignard (1683). The extent of Perrault's contribution is controversial, but I am guided by Anthony Blunt in Art and Architecture in France 1500-1700 (Harmondsworth: Penguin 1988; 1st publ. 1953) p.332. ↩

4. Thomas Kuhn: The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (University of Chicago Press 1962). Paradigm: “a cultural constellation of related ideas”. ↩

Thomas Deckker

London 2022

London 2022