thomas

deckker

architect

critical reflections

Edzell: the Paris Interlude

2024

2024

Did Lucio Costa know the Queen Mother?

2022

2022

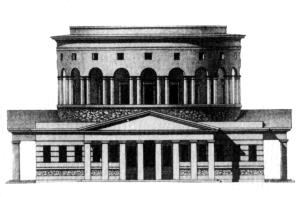

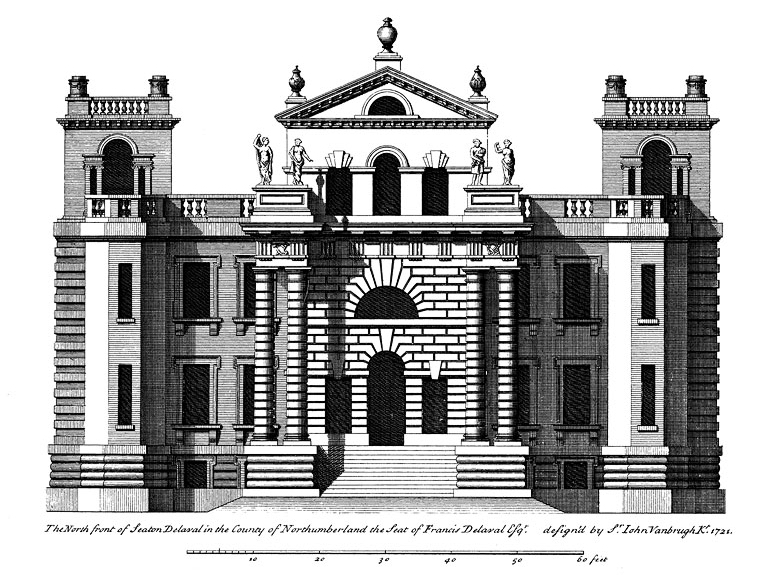

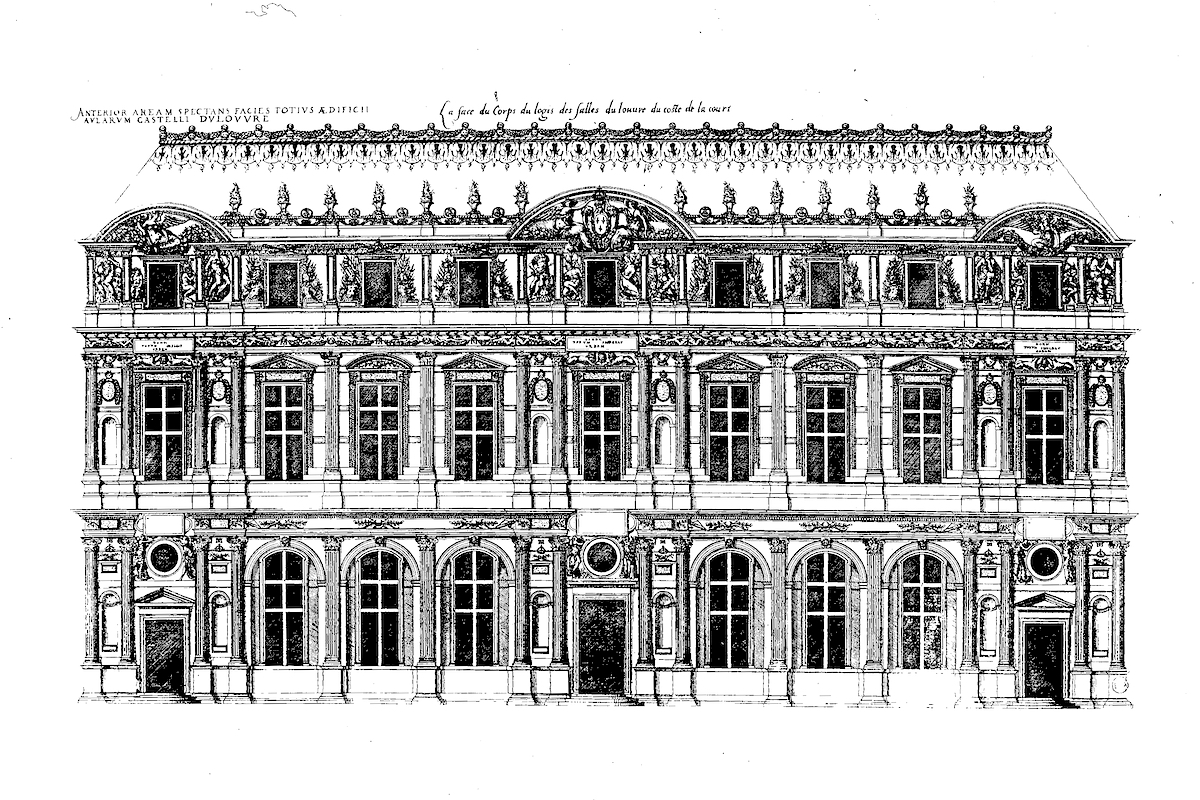

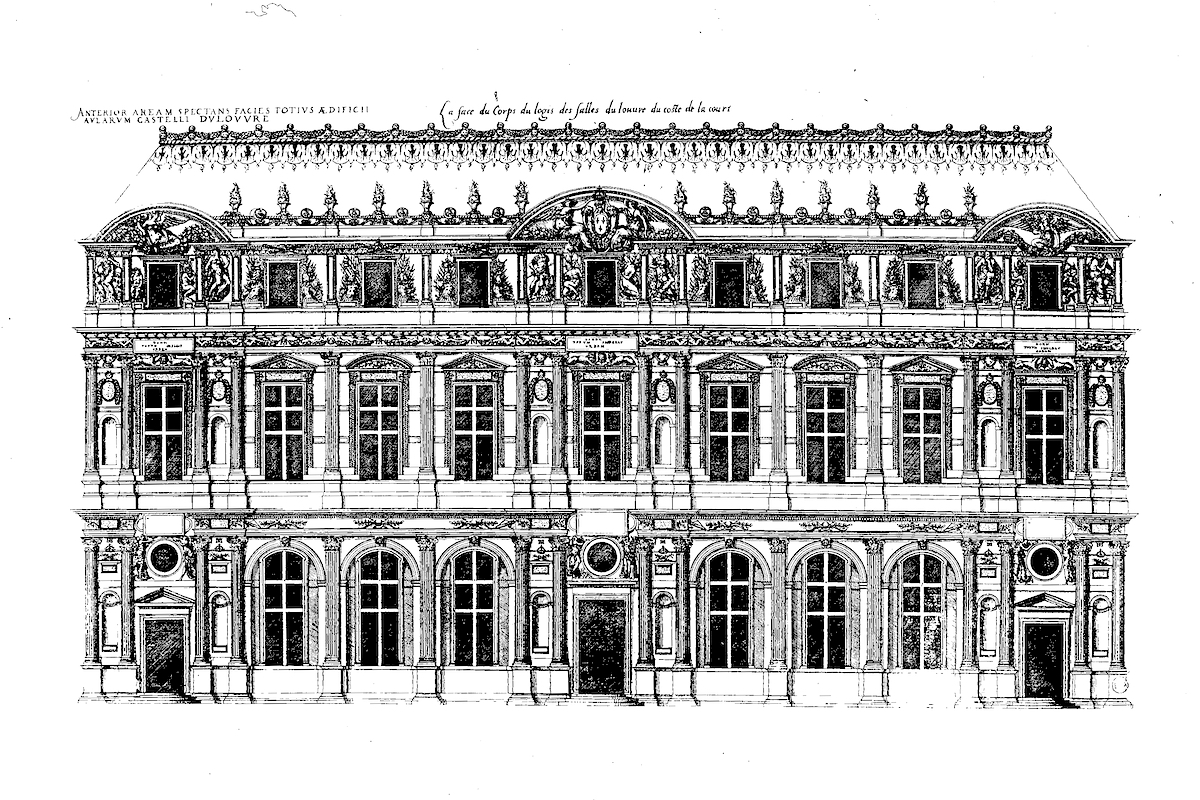

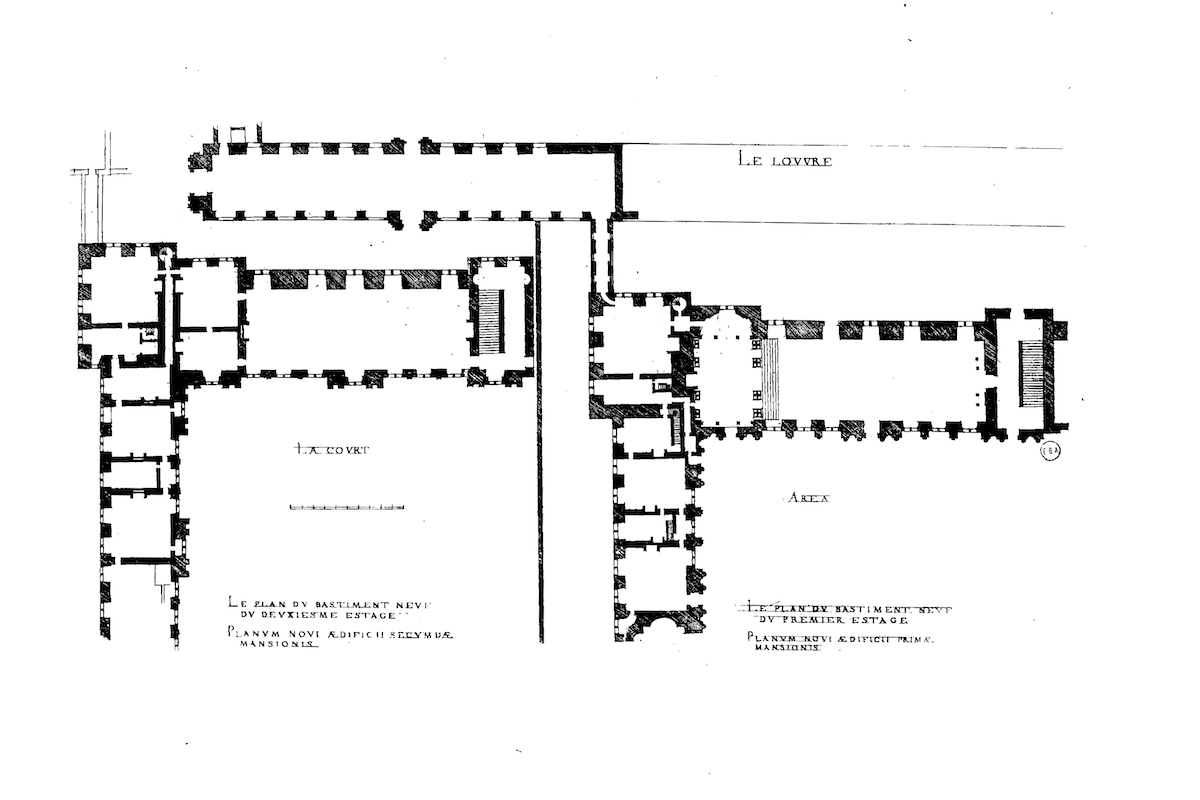

Pierre Lescot: Lescot Wing, Louvre, Paris (1546-51) from Jacques Androuet du Cerceau: Les plus excellents bastiments de France (Paris 1576)

Edzell: the Paris Interlude

David Lindsay, who designed the first Renaissance garden in Scotland in 1603, Edzell, visited Paris briefly in 1570. Edzell was a miniature French Renaissance garden, and it became apparent that, as neither David Lindsay nor Thomas Lieper, the master mason at Edzell, had any architectural training, they must have literally taken a page from the compendium of royal palaces and châteaux in France, Les plus excellents bastiments de France, to design and construct Edzell. [1] The resemblance between the garden at, for example, the Château d'Anet - which he certainly could not have seen in person - and Edzell is so strong that the importance of buildings he could have seen in person in Paris has been overlooked: the Lescot Wing, designed by Pierre Lescot, and the Petite Galerie, designed by Philibert de l'Orme, at the Louvre, and possibly the Hôtel Carnavalet, also by Lescot. The Lescot Wing and the Petite Galerie were illustrated in Les plus excellents bastiments de France, and seeing them in person would have provided a reference between actual buildings and the illustrations of châteaux he could not have seen.

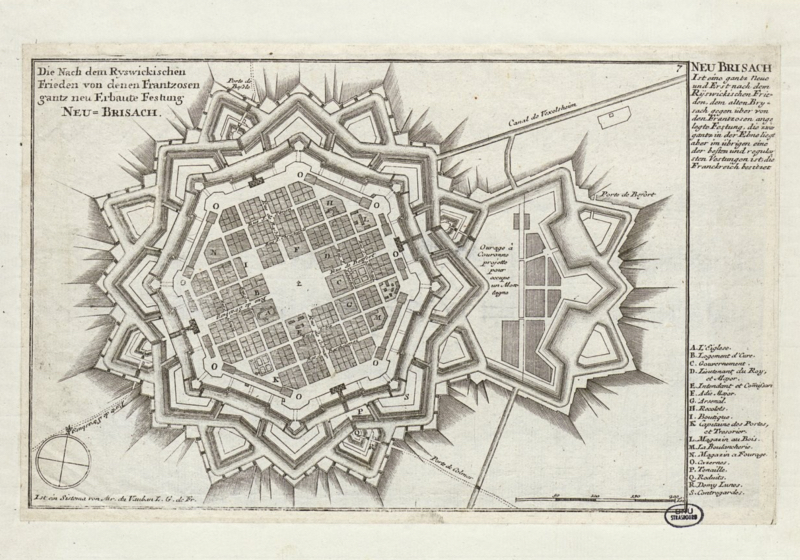

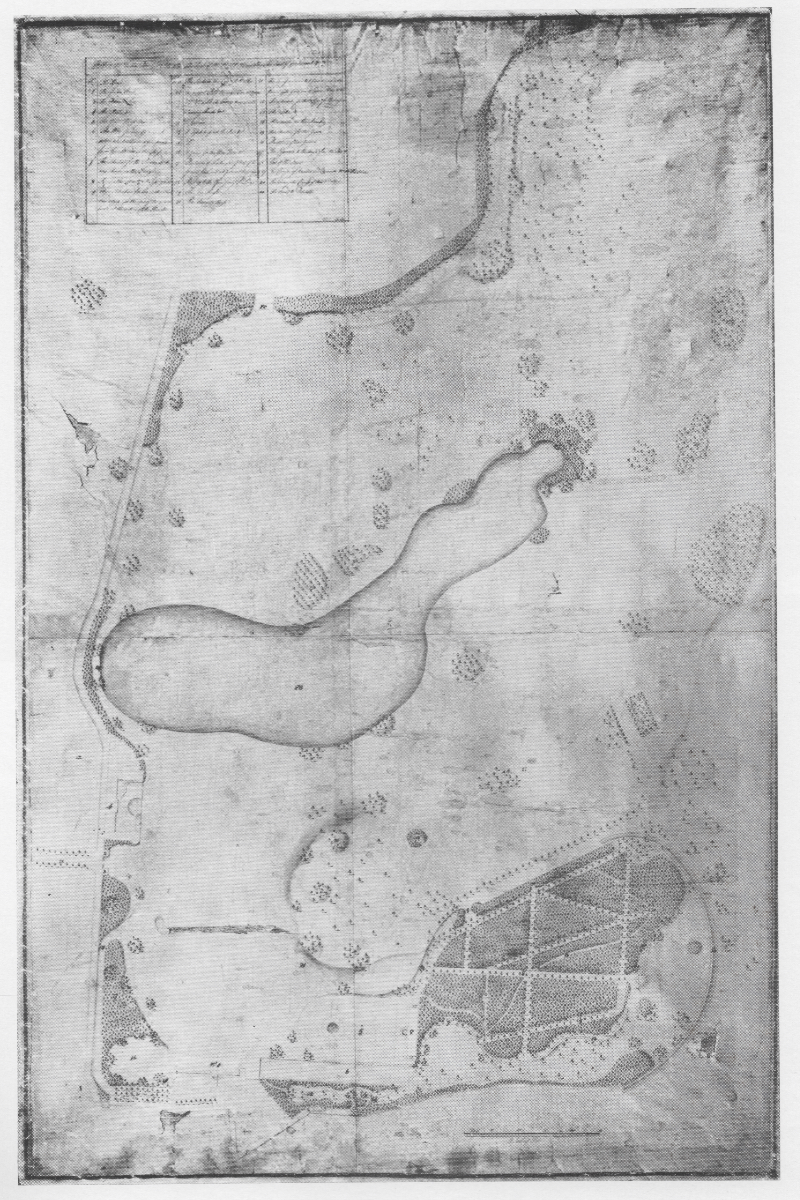

Mathieu Merian: Paris in 1615

from Adolphe Alphand: Atlas des Anciens Plans de Paris (Paris 1900)

from Adolphe Alphand: Atlas des Anciens Plans de Paris (Paris 1900)

Roll over for the location of the Louvre and the college de Reims.

Click here to see the map at a larger size.

Click here to see the map at a larger size.

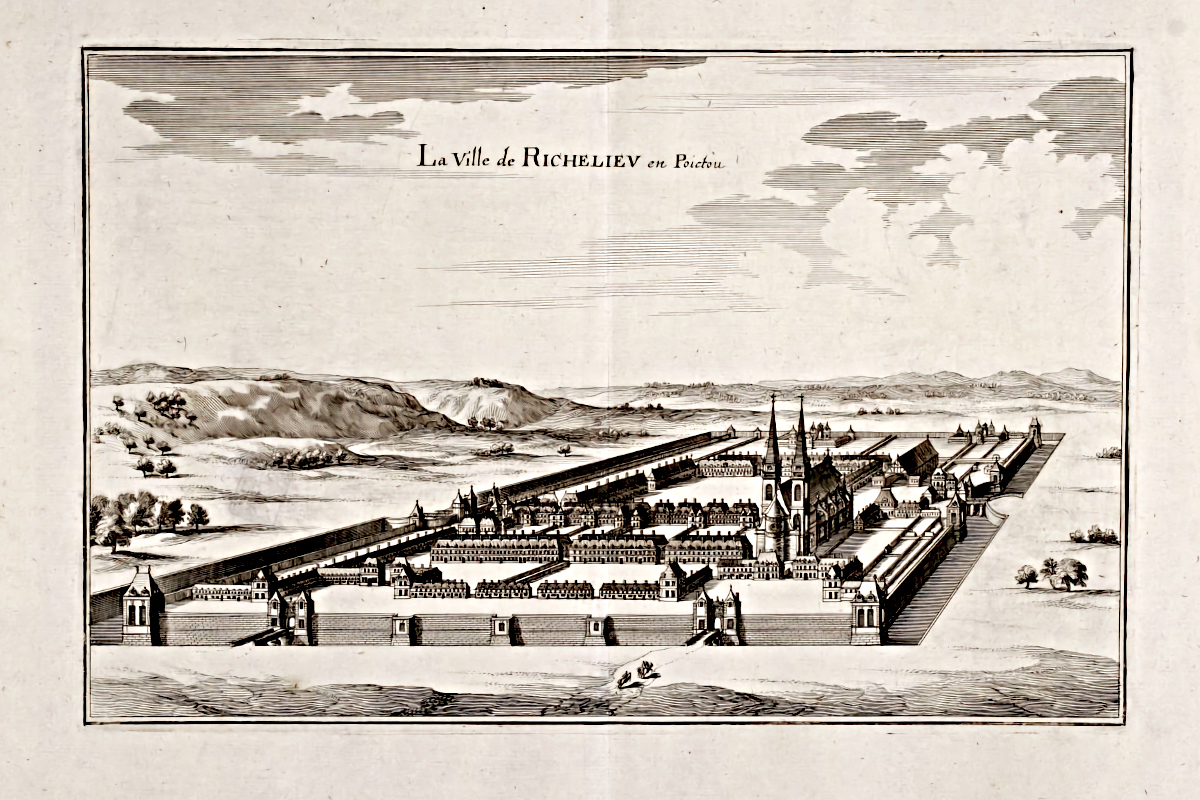

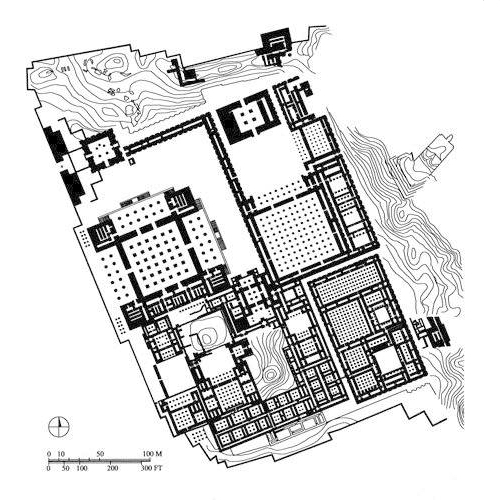

Paris, although one of the largest and most sophisticated cities in Europe in 1570, retained its medieval form, surrounded by walls. The Place Royale (now known as the Place des Vosges) has been included for reference although it was not built in 1570. Maps were not spatially accurate until the revolution in map making in the 17th century, nor were they accurate representations of buildings.

David Lindsay and his brother John stayed at the College de Reims in Paris, near the Sorbonne in what was then, and still is, the educational centre of Paris. At that time the University of Paris was organised into separate colleges, as the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge remain today. The College de Reims was founded by the Archbishop of Reims in 1400, and occupied the former Hôtel de Bourgogne in 1412, but it was not financially stable and had disappeared by the end of the 16th century. The college was on the rue de Reims, a street now disappeared underneath the outbuildings of the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève. [2]

David and John Lindsay unfortunately chose the wrong time for their visit to Paris: during their visit French Catholics began to rise up and murder Protestants, known as Huguenots. It could be assumed that they were Catholic, staying at the Catholic College de Reims, but they were, in fact, Protestant. They had to flee for their lives and return to England. As a result it is not clear what they could have seen in Paris, so the idea that they saw any particular building there is speculation, but they certainly did not see any of the châteaux outside Paris. The Lescot Wing and the Petite Galerie were important buildings, however, not only for their royal status but for their architectural innovation, and were publicly visible. At the time of their visit they were still grafted on to the side of a tower house, much as their own family home at Edzell.[3]

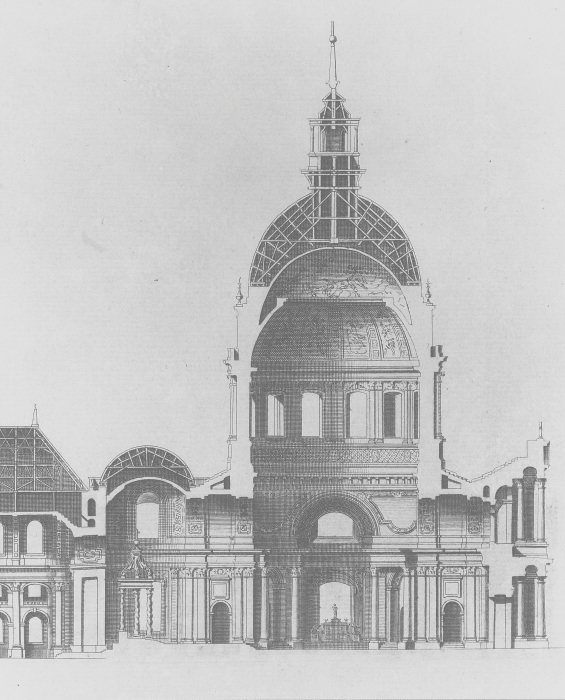

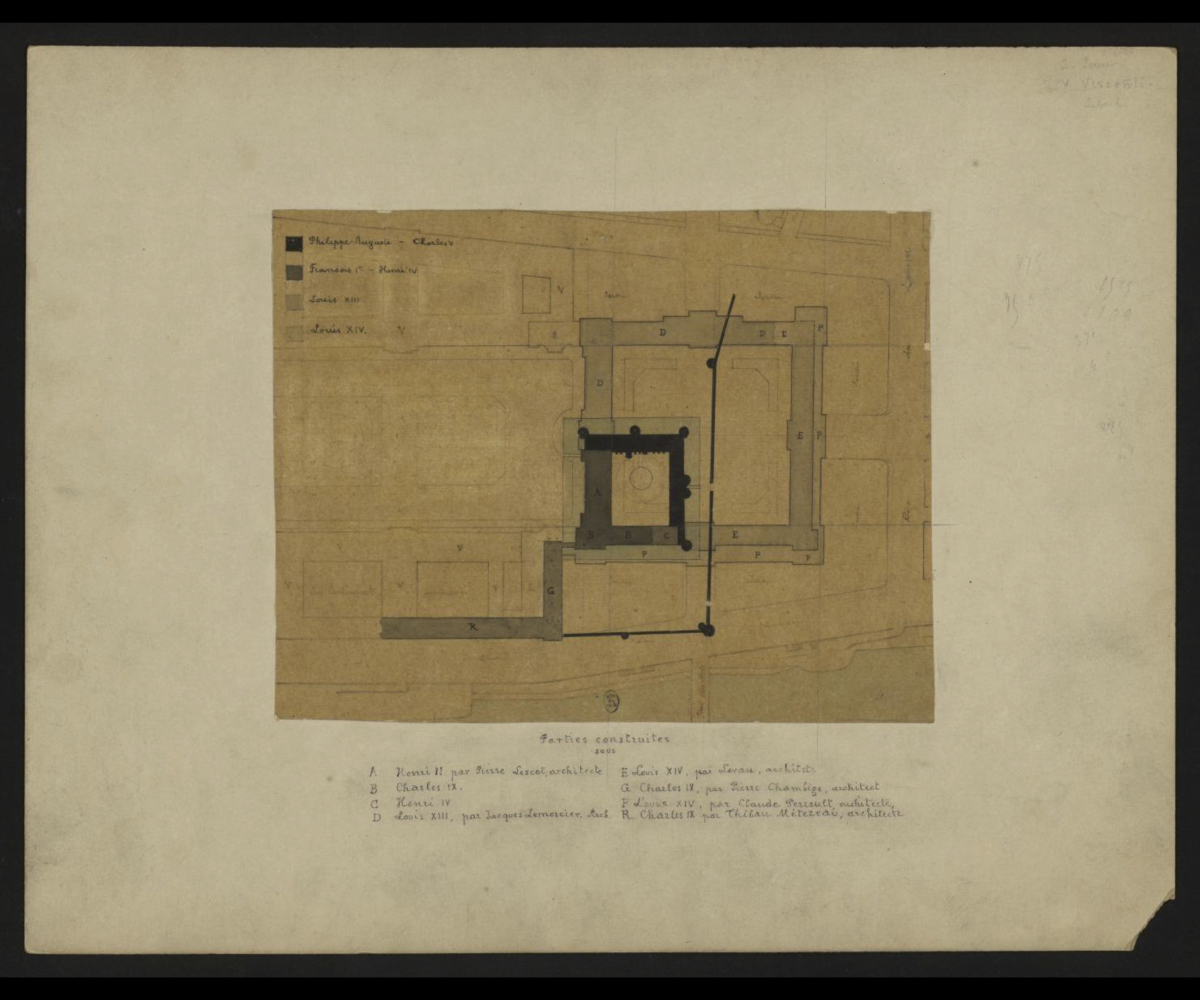

The evolution of Louvre, from Fedor Hoffbauer: Livret explicatif du diorama de Paris à travers les âges (Paris 1885)

Roll over for the location of the Lescot Wing and the Petite Galerie.

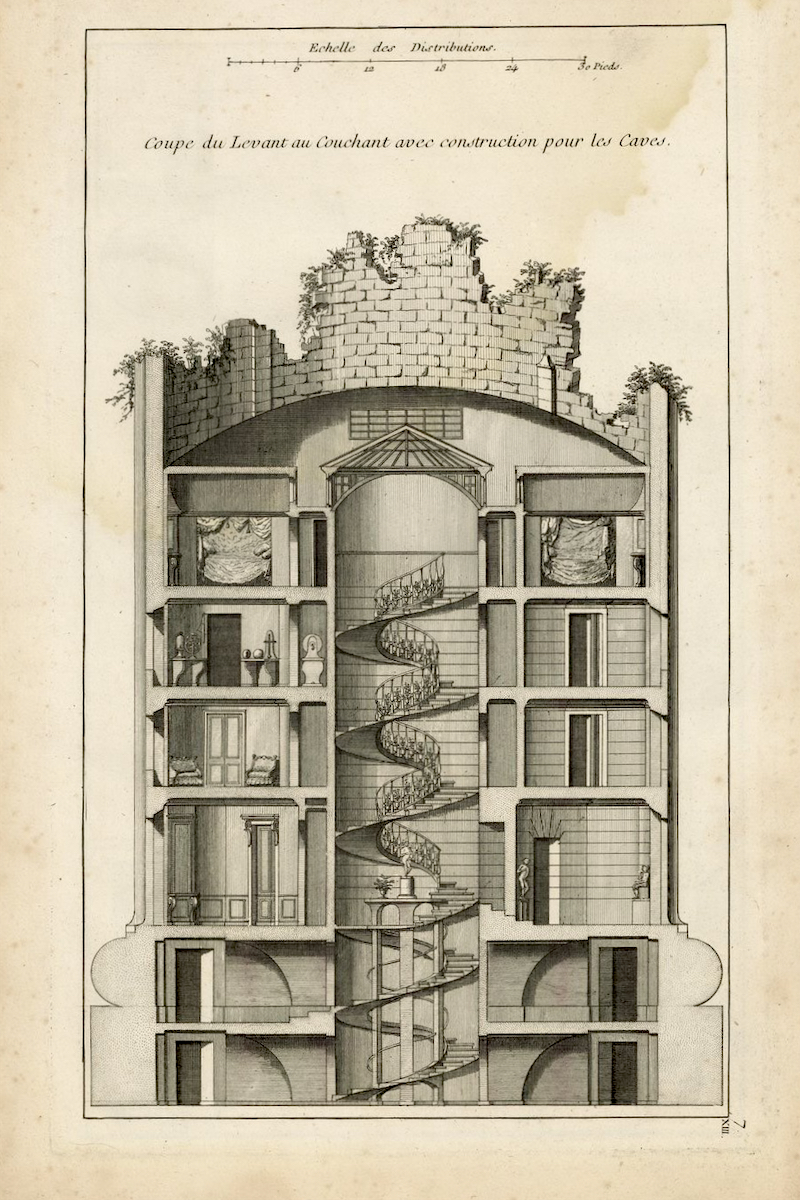

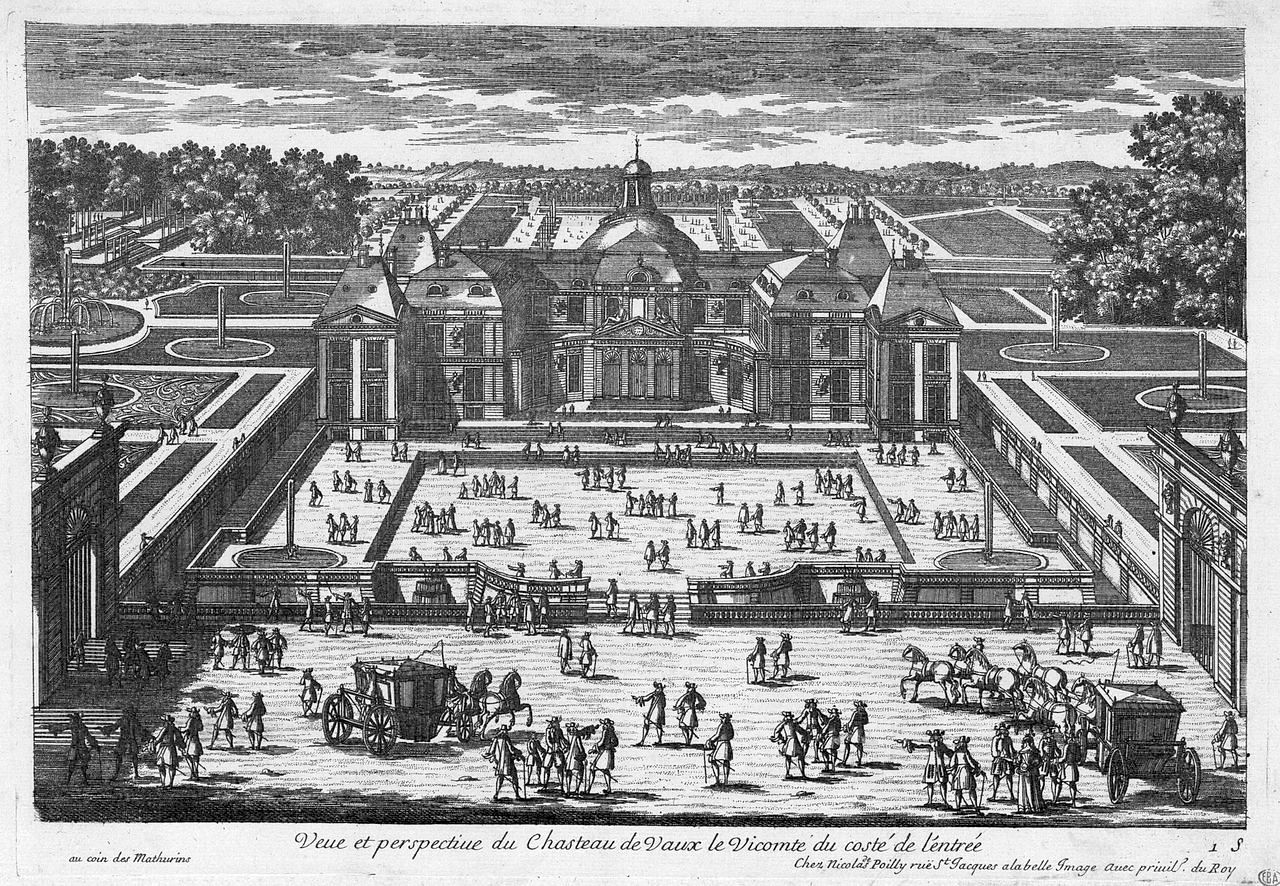

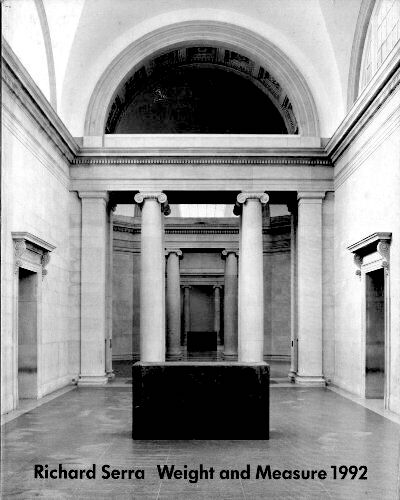

The Louvre had been built as a heavily fortified tower house adjacent to the walls of Paris, similar to the one that may be seen in the illustrated manuscript Les Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry. It consisted of a central circular keep within a square courtyard. François I had established the Louvre as the main royal residence in Paris, after maintaining his court in the Châteaux of Blois and Fontainebleau, and commissioned the architect Pierre Lescot to build a new wing to replace the western range in 1546. This was completed in 1551 and formed the first part of what is now called the Cour Carrée. The work was not complete when François I died and it was continued by Henri II who commissioned Lescot to build the Petite Galerie to connect the Louvre to the river (1563-70). Anthony Blunt speculated that the real driving force behind this commission was Diane de Poitiers, Henri II's mistress, who had commissioned Philibert de l'Orme for new buildings at the Château d'Anet (1547-52) and the Château de Chenonceau (1555). Catherine de Medici, Henri II's wife, preferred the palace of the Tuileries, then outside the walls of Paris, and commissioned Jean Bullant to build the Grande Galerie (1570-78) to connect the Louvre to the Tuileries. Work on this proceeded in stages with other parts built later by Philibert de l'Orme (1566-72), Louis Métezeau and Jacques Androuet du Cerceau (1595-1609). David Lindsay, therefore, could have seen the Petite Galerie but not the Grande Galerie. [4]

Pierre Lescot: Cour Carrée (1546-51) and Petite Galerie (1563-70), Louvre, Paris from Jacques Androuet du Cerceau: Les plus excellents bastiments de France (Paris 1576)

Jacques Lemercier: the Cour Carrée, Louvre, Paris (1625-45) based on the original wing by Pierre Lescot (1546-51)

photograph © Thomas Deckker 1997

photograph © Thomas Deckker 1997

Louvre, Paris

photograph © Thomas Deckker 1997

photograph © Thomas Deckker 1997

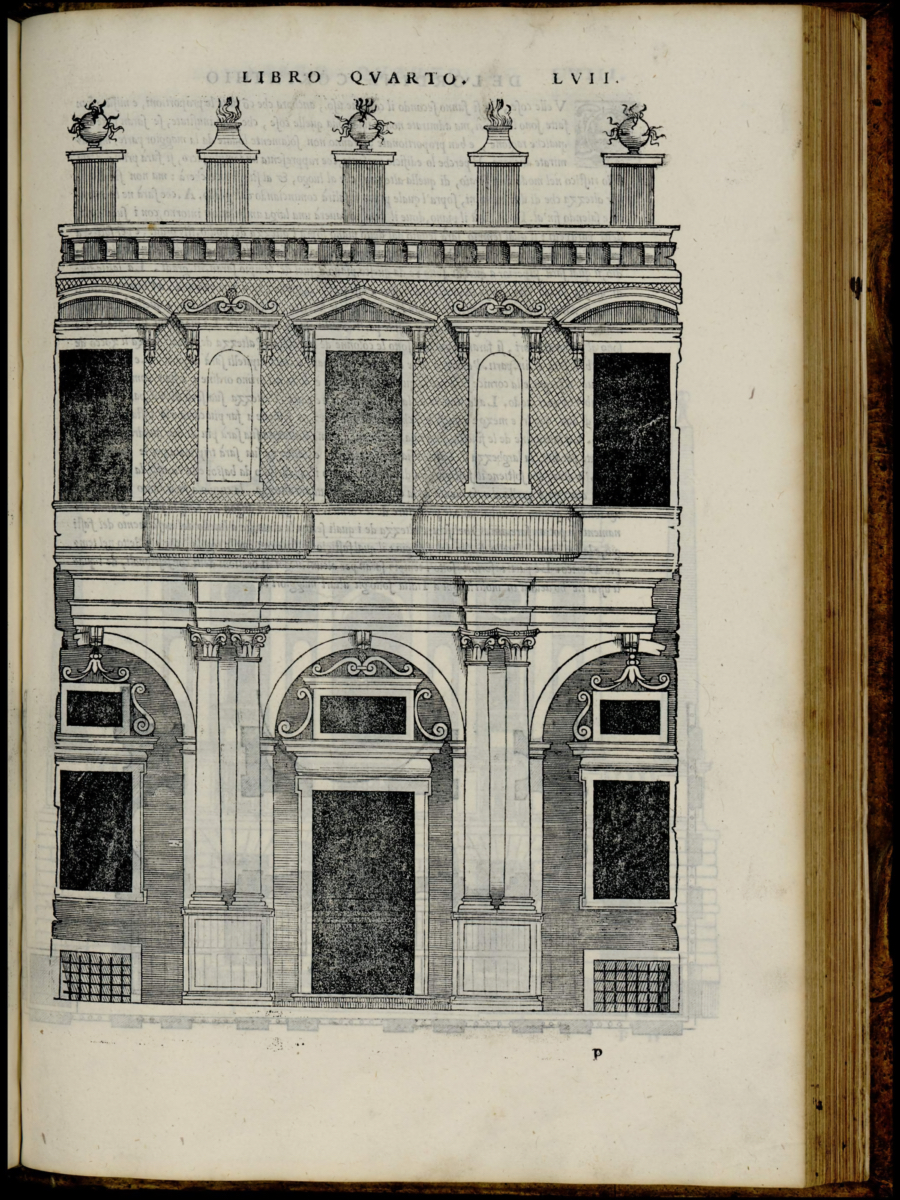

The end elevation of the Lescot Wing, the Petite Galerie and the Grande Galerie stretching along the river to the now vanished Tuileries. Note the general resemblance of the Petite Galerie to Serlio's Plate LVII and in particular the form of the dormer windows.

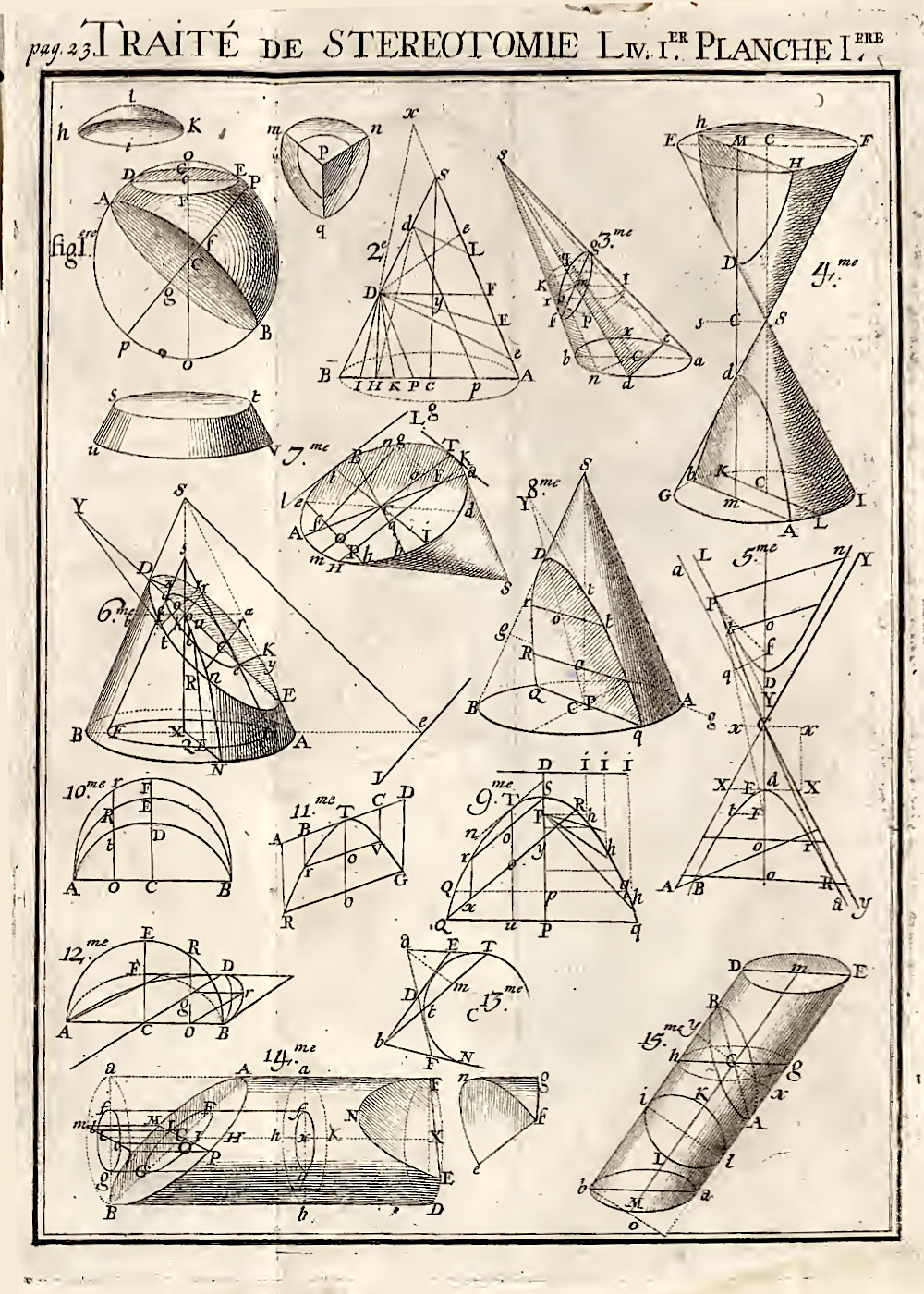

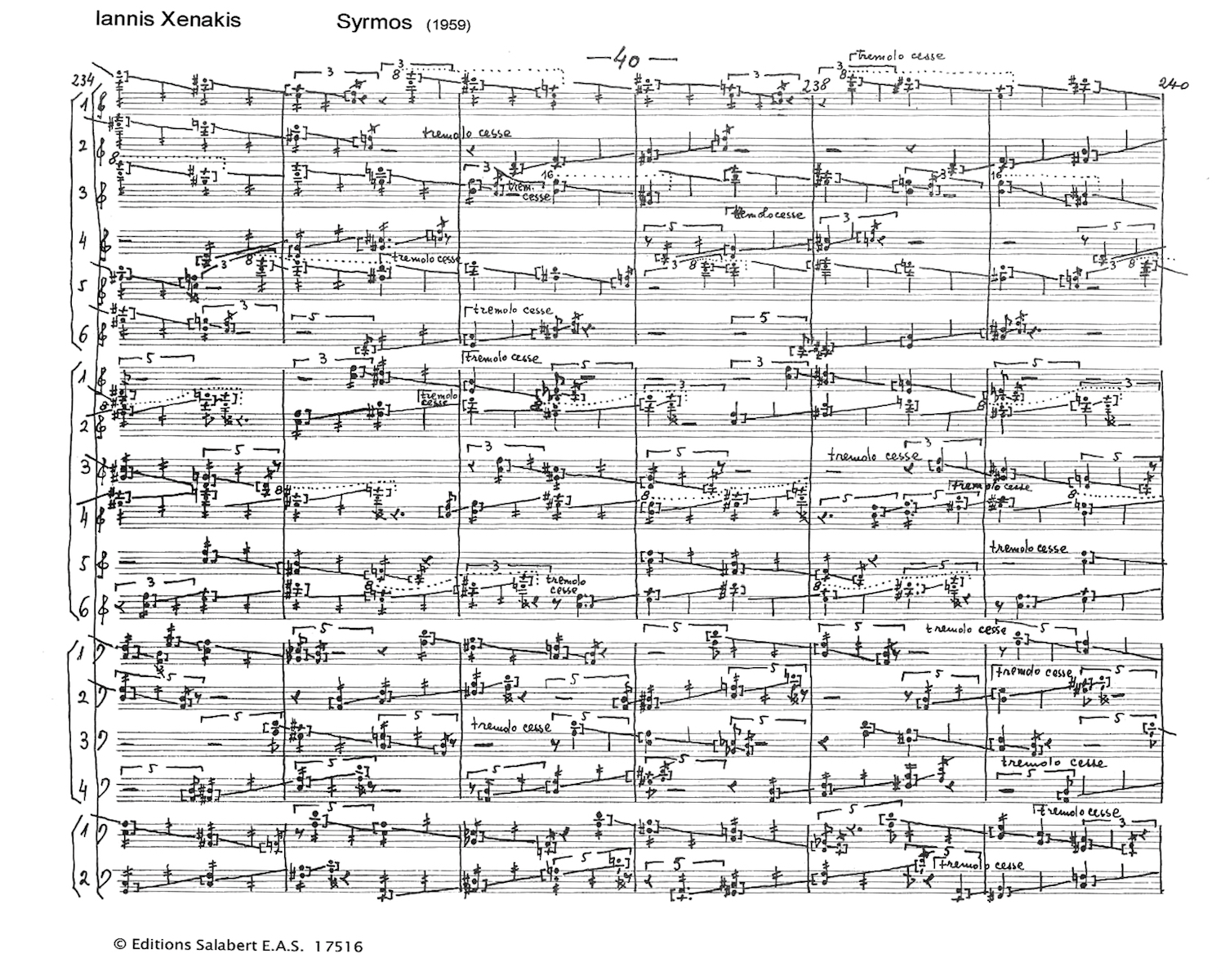

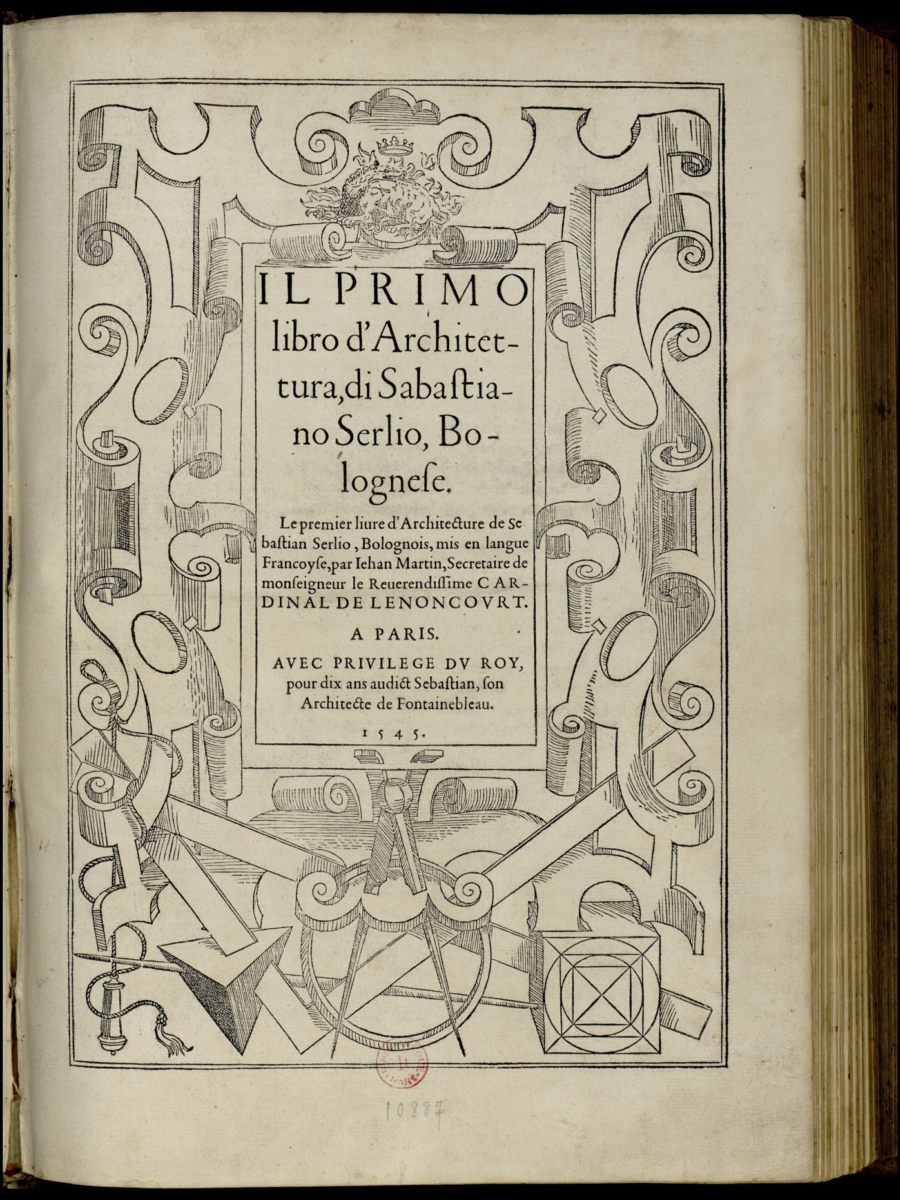

The importance of Lescot cannot be overstated. Lescot is regarded as establishing French Classicism which continued and developed for the next 250 years. The development in theory and practice from the Renaissance style associated with François I to Classicism can be seen as an architectural equivalent to what Thomas Kuhn called a 'paradigmatic shift' in the history of science, that is from one relatively stable set of beliefs on, for example, building types, construction and aesthetic principles, to another. Lescot established those aesthetic principles of articulation and decoration at a stroke at the Lescot Wing. The new design process in which forms, spaces, connections and appearance would be worked out on paper according to aesthetic principles before construction meant that designs could be transmitted in treatises, a process begun during the Renaissance in Italy and perfected in the next century with the development of descriptive and projective geometry. Philibert de l'Orme had studied in Italy but Lescot's principal source of Renaissance architecture were the treatises of the Italian architect Sebastiano Serlio, who had been invited to France by François I in 1540. The entire Book 1 described how to draw in 2 dimensions, and the entire Book 2 described how to draw in 3 dimensions, before buildings of the Roman Empire were illustrated in Book 3. These actual examples were significantly more important for practicing architects than Vitruvius. [5]

Sebastiano Serlio: Il Primo libro d'architettura (Paris 1545): Title Page [6]

The title page of the French translation, published in Paris in 1545. Cardinal de Lenoncourt is undoubtedly Philippe de Lenoncourt who sponsored the translation and publication of Architecture ou Art de bien bastir de Marc Vitruve Pollion, the French translation of Vitruvius, in 1547.

The title page of the French translation, published in Paris in 1545. Cardinal de Lenoncourt is undoubtedly Philippe de Lenoncourt who sponsored the translation and publication of Architecture ou Art de bien bastir de Marc Vitruve Pollion, the French translation of Vitruvius, in 1547.

Sebastiano Serlio: Libro Quarto Plate LVII

This plate shows an elevation with a Corinthian order. The ground floor is drawn as a portico, but this would have been unfeasible in the climate of northern Europe. Note the pilasters along the balustrade.

This plate shows an elevation with a Corinthian order. The ground floor is drawn as a portico, but this would have been unfeasible in the climate of northern Europe. Note the pilasters along the balustrade.

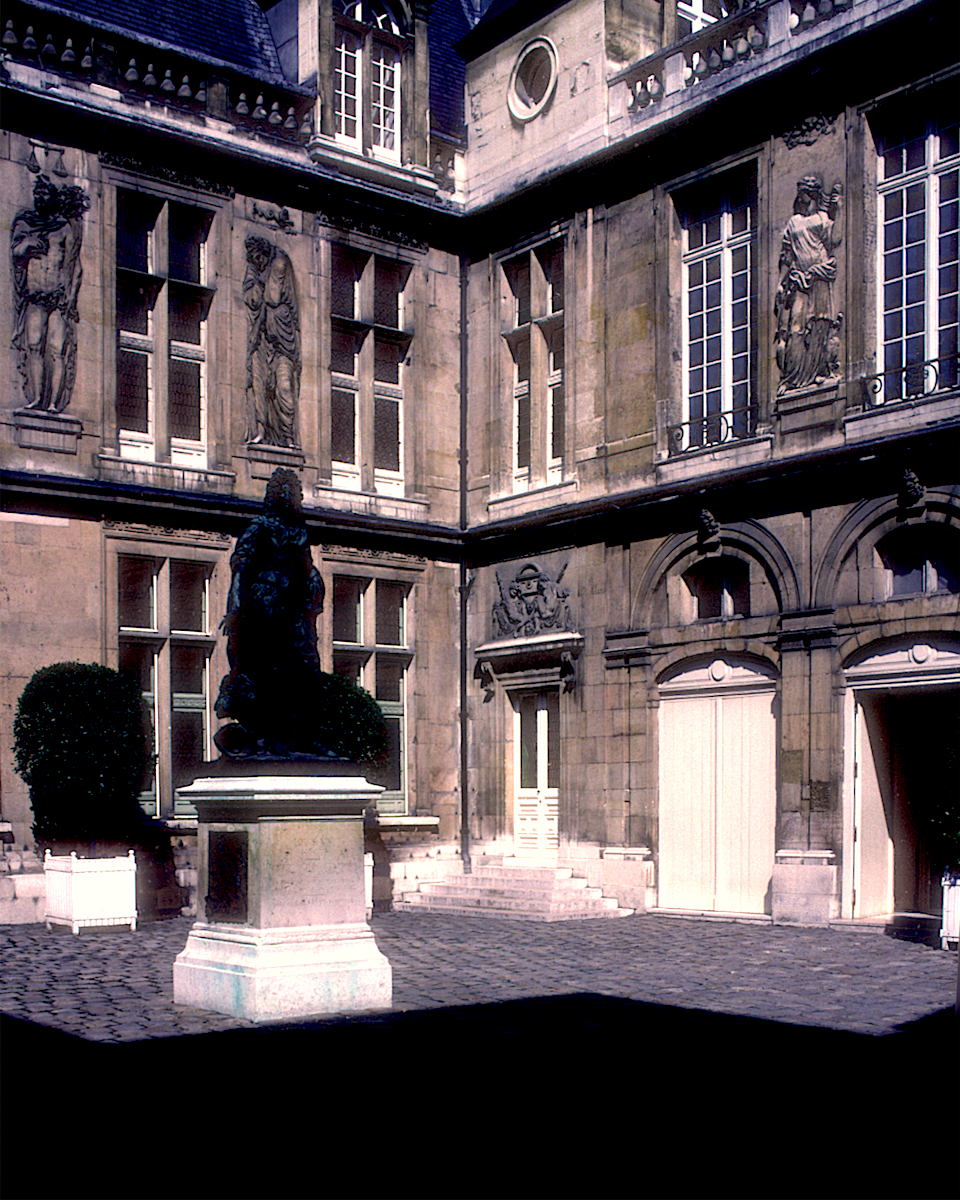

Pierre Lescot: Hôtel Carnavalet, Paris

photograph © Thomas Deckker 1997

photograph © Thomas Deckker 1997

Note the general resemblance of the Hôtel Carnavalet to Serlio's Plate LVII: the arcades on the ground floor, the alternate glazed and solid bays (later filled with sculptural panels) on the first floor, and Serlio's pilasters on the balustrade articulated as dormer windows.

The Hôtel Carnavalet is the only surviving 16th century hôtel particulière (private mansion) in Paris, although much altered. It was originally built for a private owner, Jacques des Ligneris, between 1548 and 1560. As a private building it may not have been accessible to the Lindsays in any case and a visit is possible but not plausible given the their very short stay in Paris. The resemblance of the sculptural bays and the dormer windows to the garden wall at Edzell may have been no more than because both the Lescot Wing and the Hôtel Carnavalet were designed by Lescot.

Summer House, Edzell

© Thomas Deckker 2011

© Thomas Deckker 2011

There is no suggestion here that David Lindsay should have articulated the garden wall at Edzell as Lescot had done at the Louvre or the Hôtel Carnavalet. The wall was, after all, a garden wall with more in common with other garden walls than with royal or aristocratic palaces. However note the pilasters sticking up above the wall, each with a niche that resembles a window. In Renaissance architecture a niche and a window were syntactically equivalent, of course, so these may be read as dormer windows. Each dormer relates to a sculptural bay, similar but not identical to Lescot's work.

It is not implausible to think of David Lindsay, in love with France and French architecture, risking his life to seek out the latest buildings in real life and harbouring a desire to reproduce on his estate in Scotland what he saw very briefly in Paris and then at leisure in Les plus excellents bastiments de France. John Lindsay, too, maintained his connection to France, to which he was appointed Scottish ambassador in 1597, although he died shortly after. Although there is as yet no evidence it is not implausible that they shared a copy of Les plus excellents bastiments de France. The mystery of how a French Renaissance garden appeared in Scotland has now been solved beyond reasonable doubt, and after 400 years this is sufficient for the time being.

It is not implausible to think of David Lindsay, in love with France and French architecture, risking his life to seek out the latest buildings in real life and harbouring a desire to reproduce on his estate in Scotland what he saw very briefly in Paris and then at leisure in Les plus excellents bastiments de France. John Lindsay, too, maintained his connection to France, to which he was appointed Scottish ambassador in 1597, although he died shortly after. Although there is as yet no evidence it is not implausible that they shared a copy of Les plus excellents bastiments de France. The mystery of how a French Renaissance garden appeared in Scotland has now been solved beyond reasonable doubt, and after 400 years this is sufficient for the time being.

Footnotes

1. Jacques Androuet du Cerceau: Les plus excellents bastiments de France, (Paris, 1576 and 1579). ↩

2. Andrew Jervise: The History and Traditions of the Land of the Lindsays in Angus and Mearns, with Notices of Alyth and Meigle (1st publ. Edinburgh: Sutherland & Knox 1853; 2nd ed. Edinburgh 1888) ↩

3. Académie nationale de Reims: Travaux de l'Académie nationale de Reims Vol. 104 (Reims 1897). Chapter 1: Le Collège de Reims depuis sa fondation jusqu'au XVIIe siècle (1412-1593). ↩

4. Anthony Blunt: Art and Architecture in France 1500-1700 (Harmondsworth: Penguin 1988; 1st publ. 1953) ↩

5. Thomas Kuhn: The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (University of Chicago Press 1962). Paradigm: "a cultural constellation of related ideas". ↩

6. Sebastiano Serlio: Il Primo libro d'architettura (Paris 1545). Translated by Ian Martin and dedicated to Cardinal Lenoncourt. The French translation contains Books 1-5. ↩

What did they eat?

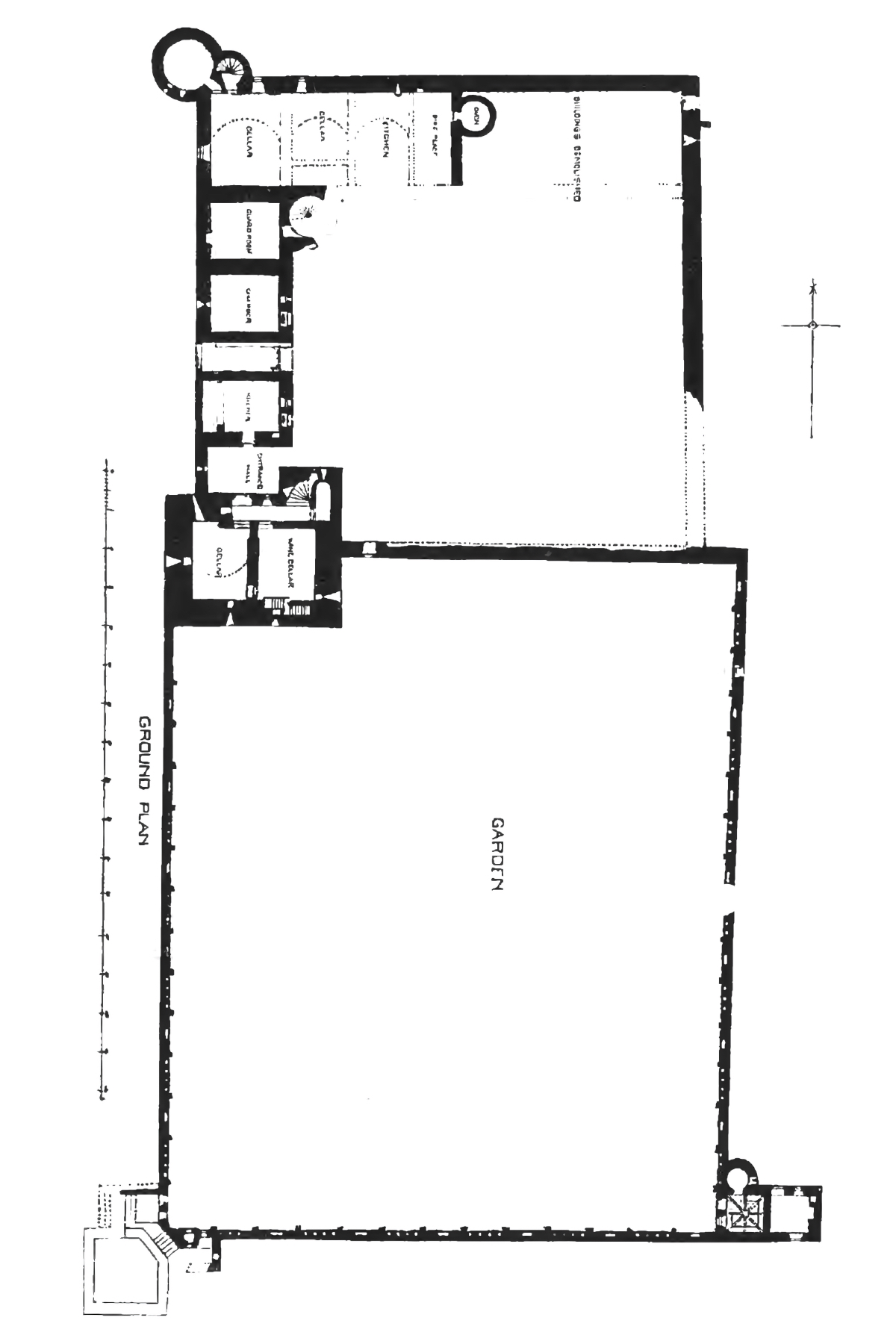

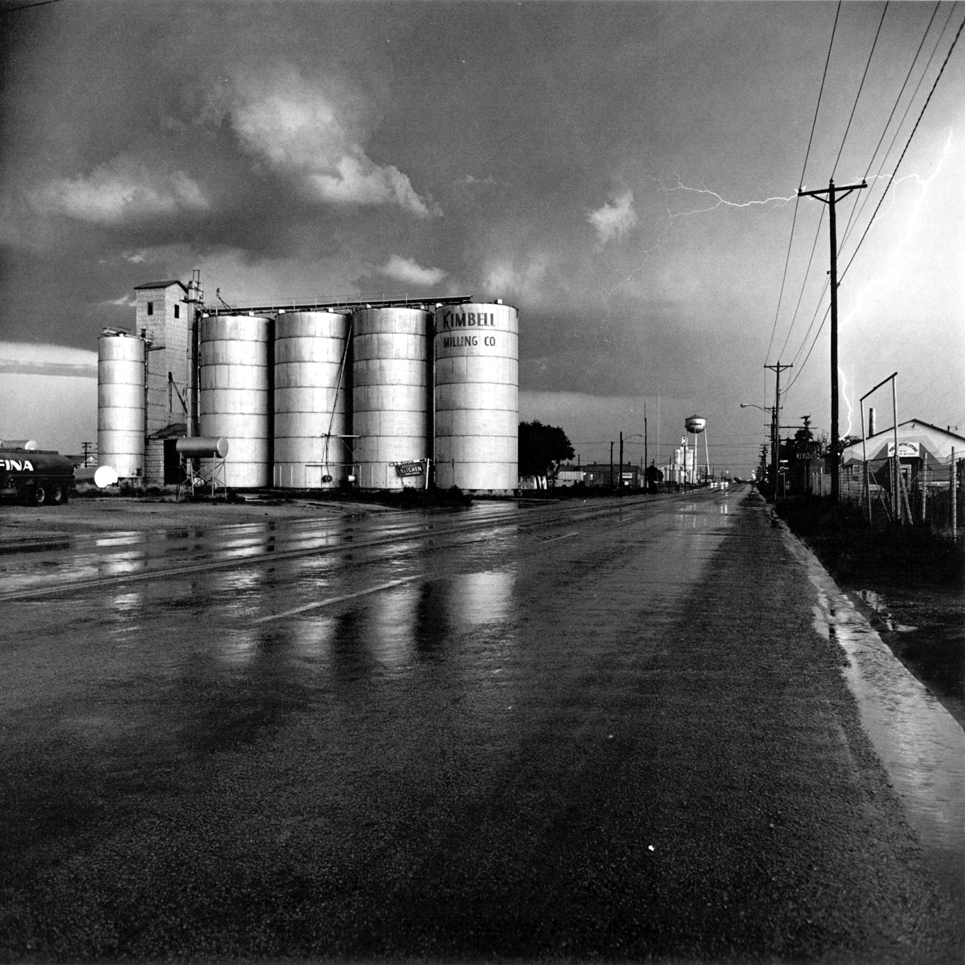

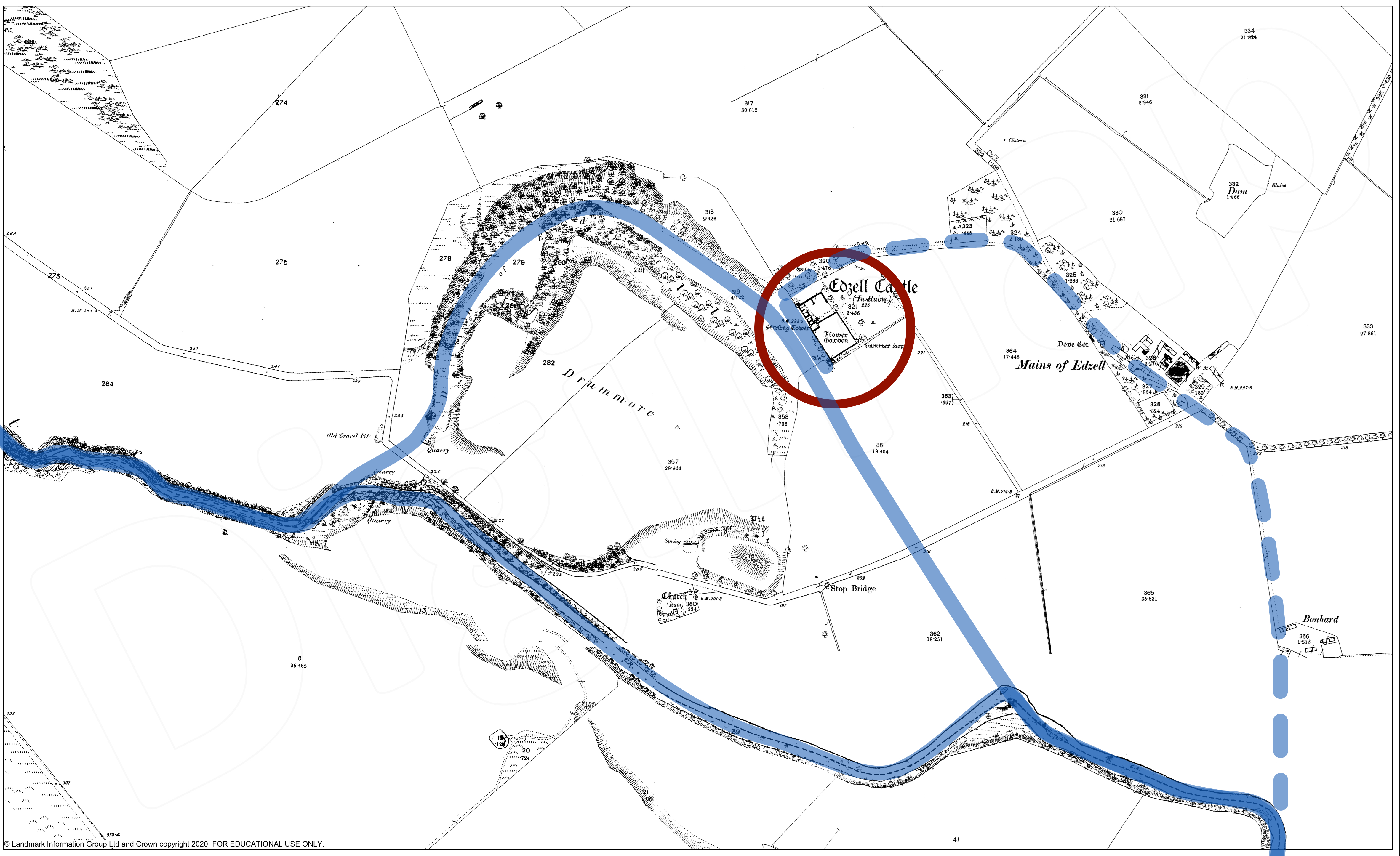

Reconstruction of the site of Edzell in 1600

The River Esk ran in front of the house, serving the kitchen and bathhouse, with a possible branch running along the northern boundary to the farm, the Mains of Edzell, which still exists. The hunting forest to the north is now cleared for farming.

Edzell was extraordinarily well served for food. This was not the usual state of affairs in Scotland at the time, but followed new customs from France. Medieval court food was highly spiced (mincemeat is a distant survivor of medieval food) with elaborate ornamental presentation, but the new cuisine utilised fresh vegetables and dairy produce, with light sauces. David Lindsay is known to have owned a French treatise on agriculture, La Maison Rustique, one of several treatises which accompanied the revolution in architecture in the Loire in the mid 16th century:

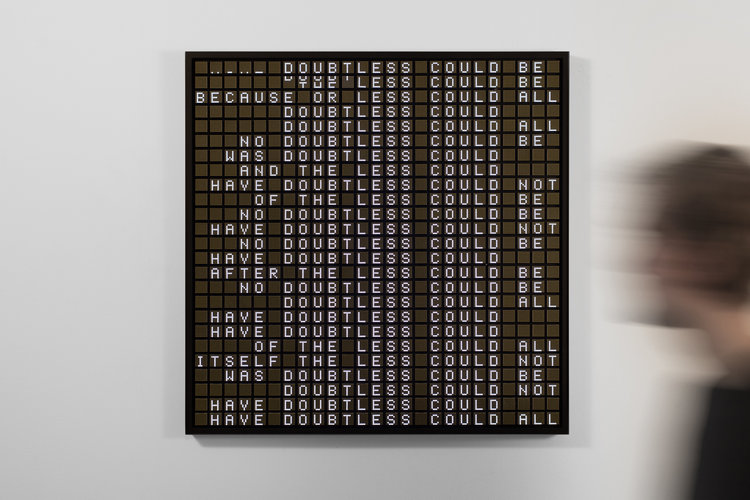

in which is contained all that may be required to build a country house, feed and medicate cattle and poultry of all kinds, erect gardens, both vegetable plots and flower beds, govern bees, plant and sow all kinds of fruit trees, maintain meadows, fishponds and ponds, plow the grain fields, shape vines, planting woods of full grown tress and coppices, build rabbit warrens, heron roosts and a park for wild animals. [7]

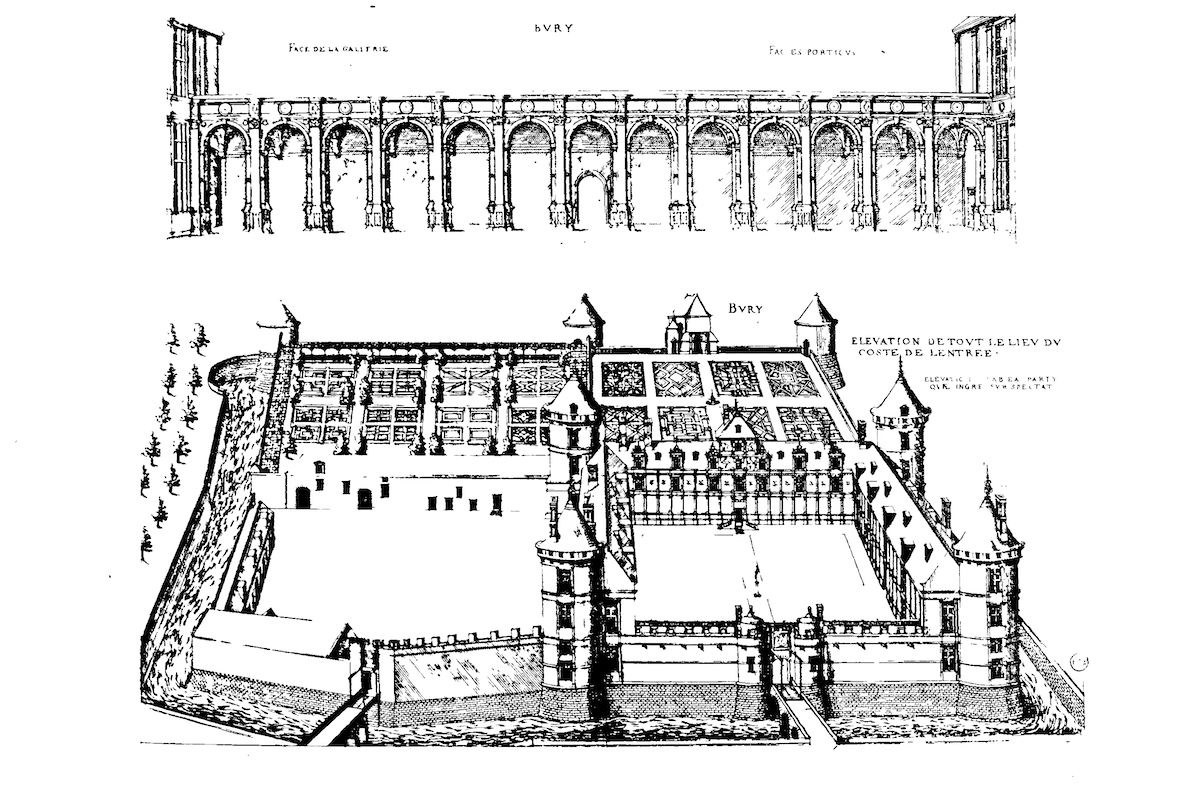

Chateau de Bury

Jacques Androuet du Cerceau: Les plus excellents Bastiments de France (Paris 1576/79)

Jacques Androuet du Cerceau: Les plus excellents Bastiments de France (Paris 1576/79)

The gardens attached to French Renaissance châteaux were not ornamental or fortuitous in design: they had many practical and symbolic functions and were fully integrated into a set of ideas about food, medicine, hygiene and pleasure. The herbs grown in the parterres, or planting beds, were used to flavour food, for medicine, for scenting bath water, for the pleasure of scent, and even for hosting bees, essential for pollination and honey. The shape of the parterres was symbolic of fertility, and the patterns of the beds were also used for women's clothes.

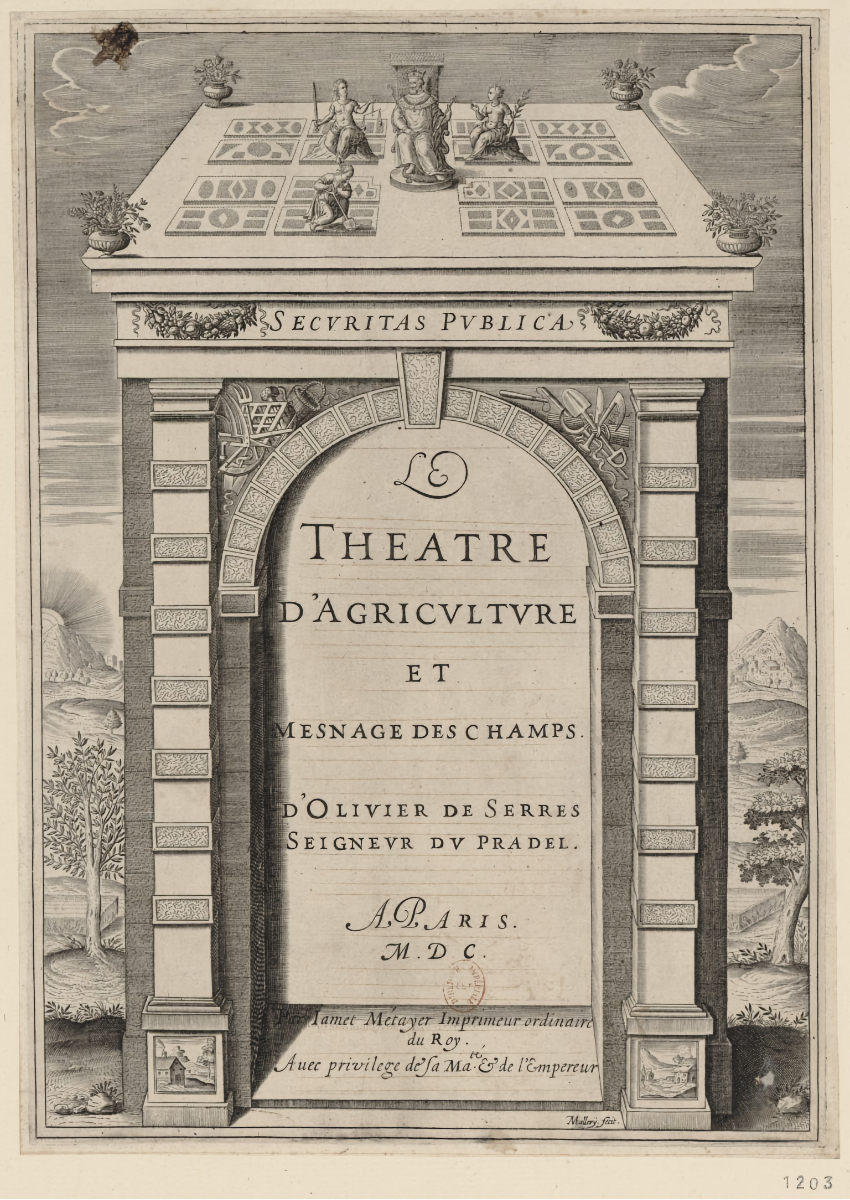

Olivier de Serres: Le théâtre d'agriculture et mésnage des champs (Paris 1600)

The title page shows Henri IV in a square garden. Henri IV was Protestant, and Serres a Huguenot. The portrayal of Henri IV may be interpreted as an appeal for support or protection, as Huguenots were persecuted at the time. The square garden resembles the original Place Royale, part of the urban improvements of Henri IV. This provided the model for squares in London such as Covent Garden.

The title page shows Henri IV in a square garden. Henri IV was Protestant, and Serres a Huguenot. The portrayal of Henri IV may be interpreted as an appeal for support or protection, as Huguenots were persecuted at the time. The square garden resembles the original Place Royale, part of the urban improvements of Henri IV. This provided the model for squares in London such as Covent Garden.

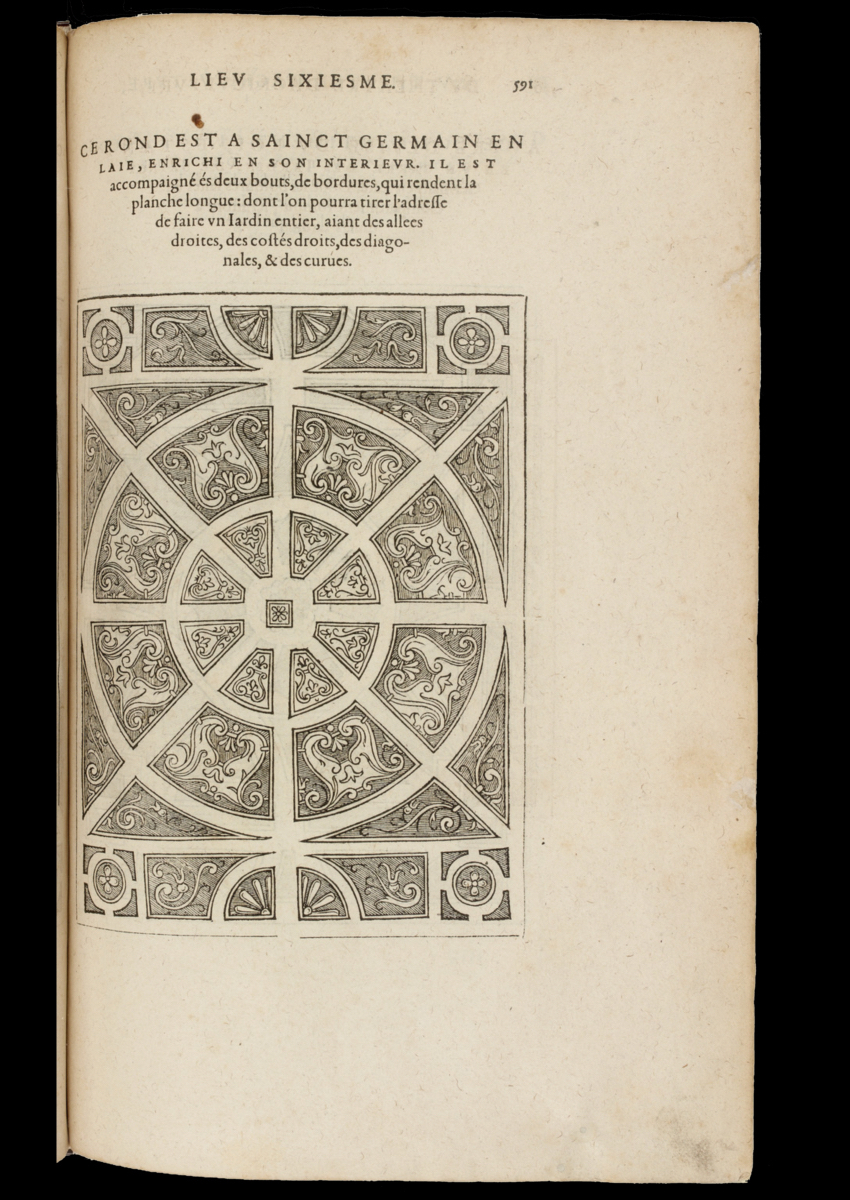

Olivier de Serres: Le théâtre d'agriculture et mésnage des champs (Paris 1600)

An example of a garden formed of ornamental parterres similar to the one at Edzell. Le théâtre d'agriculture et mésnage des champs was not just about gardens but included hunting, fishing and animal husbandry.

An example of a garden formed of ornamental parterres similar to the one at Edzell. Le théâtre d'agriculture et mésnage des champs was not just about gardens but included hunting, fishing and animal husbandry.

All the gardens shown in Les plus excellents bastiments de France had pavilions for bathing, eating and other more private pleasures, away from the prying eyes of the household. It was usual for lords and ladies to retire to a separate pavilion to eat dessert, away from the communal main course in the main hall. The only known survivor of this practice is in the colleges in Oxford and Cambridge, where Fellows dine at a High Table with students in Hall, and then retire to the Senior Common Room for port and dessert. The summer house at Edzell was undoubtedly for this purpose, with a stone table and benches, and a private room upstairs for more intimate occasions. [8]

The new interest in vegetables, rather than meat, had many causes. The discovery of ancient texts on cuisine such as De re culinaria by the late Roman author Apicius, and on natural history, agronomy, and medicine, encouraged scientific interest in edible plants. The revolution in cooking was accompanied by a revolution in medicine, partly due to translations of the Roman Greek physician Claudius Galen of Pergamon, and partly by contemporary physicians such as Andreas Vesalius, whose De humani corporis favbrica, which laid the foundations of modern anatomy, was published in 1542. [9]

Footnotes

7. Charles Estienne: La Maison Rustique (Paris 1564; 2nd edition rev. by Jean Liébault, Paris 1589) ↩

8. Mark Girouard: Life in the English Country House: A Social and Architectural History (Yale University Press 1994) ↩

9. Susan Pinkard: A Revolution in Taste: The Rise of French Cuisine 1650-1800 (Cambridge University Press 2009) ↩

Thomas Deckker

London 2024

London 2024