thomas

deckker

architect

critical reflections

The Arcades Project

2023

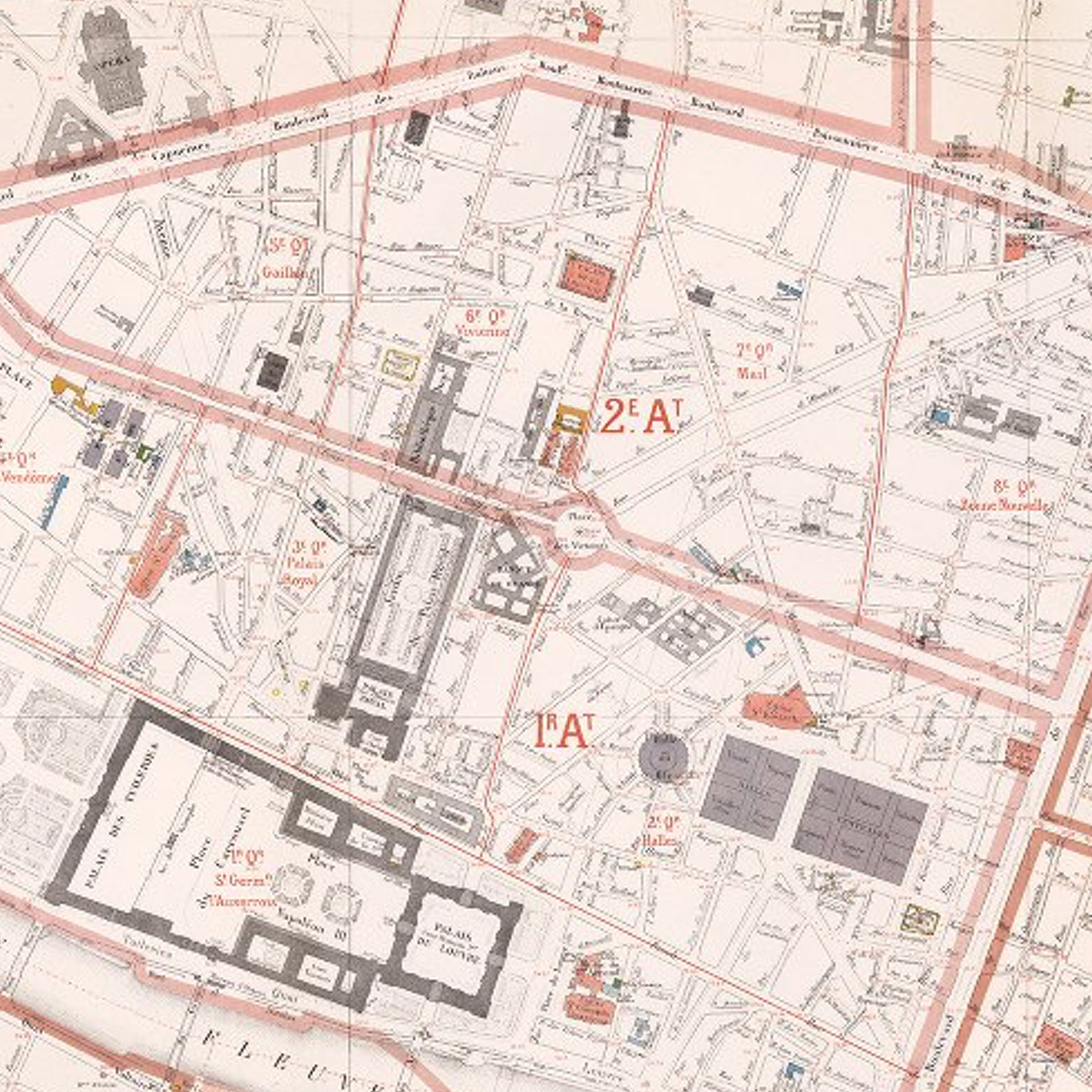

Nouveau plan de la ville de Paris 1828

David Rumsey Maps

David Rumsey Maps

roll over for location of the Galerie Vivienne

The Arcades Project

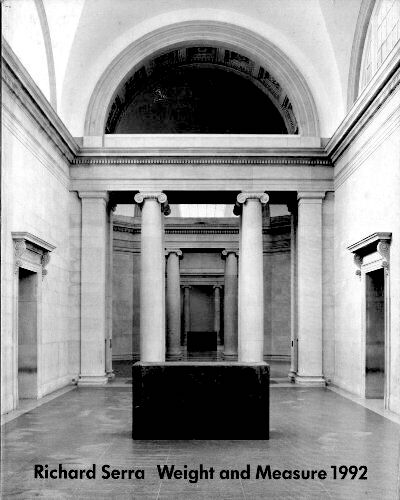

I became aware of the arcades in Paris, while a student at the Architectural Association School, through the work of Walter Benjamin. Benjamin proposed, in 'Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century', that the arcades were the first and archetypal spaces of capitalism in Paris, metonyms for the revolution of modernity. He wrote Passagenwerk or The Arcades Project in Henri Labrouste's famous reading room at the Bibliotheque Nationale, just across the Rue Vivienne from the Galerie Vivienne. He gave two reasons for their construction:

Most of the Paris arcades come into being in the decade and a half after 1822. The first condition for their emergence is the boom in the textile trade… The second condition for the emergence of the arcades is the beginning of iron construction.[1]

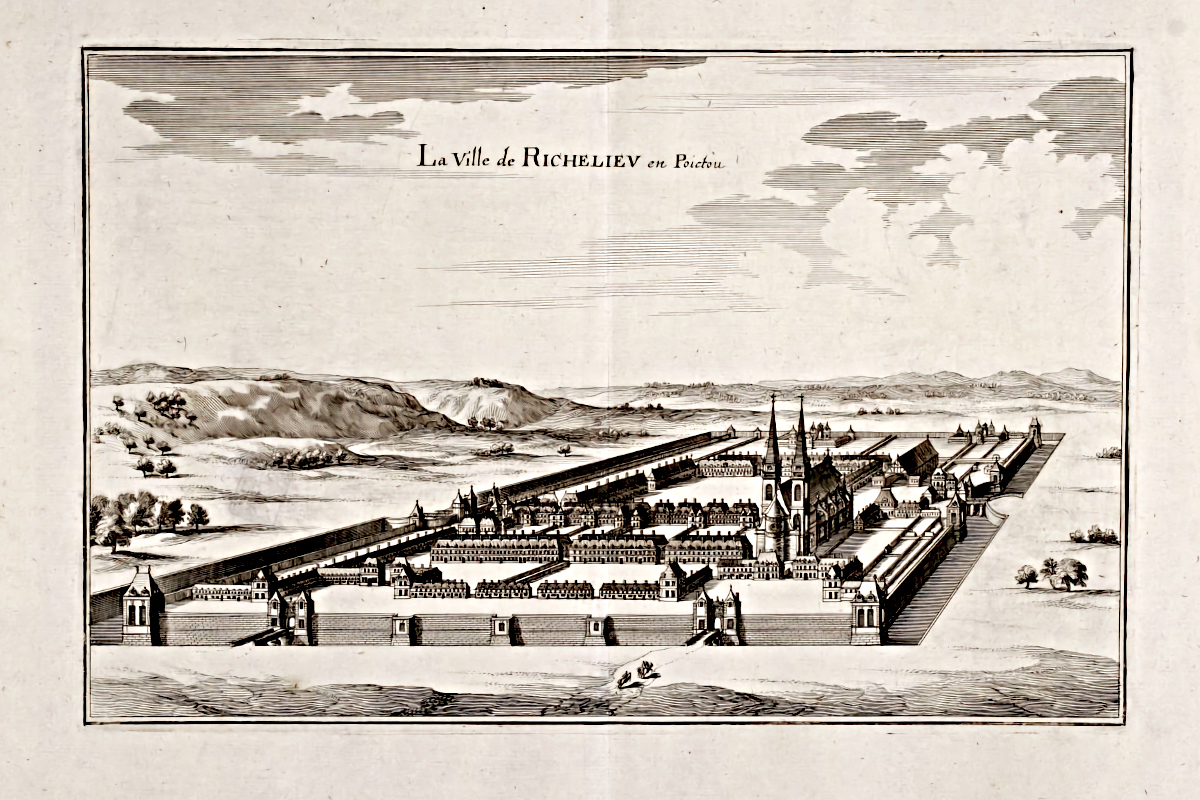

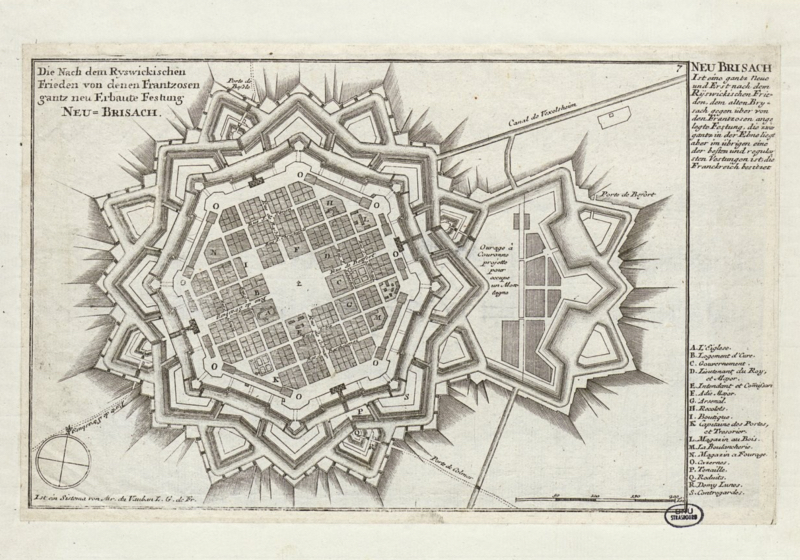

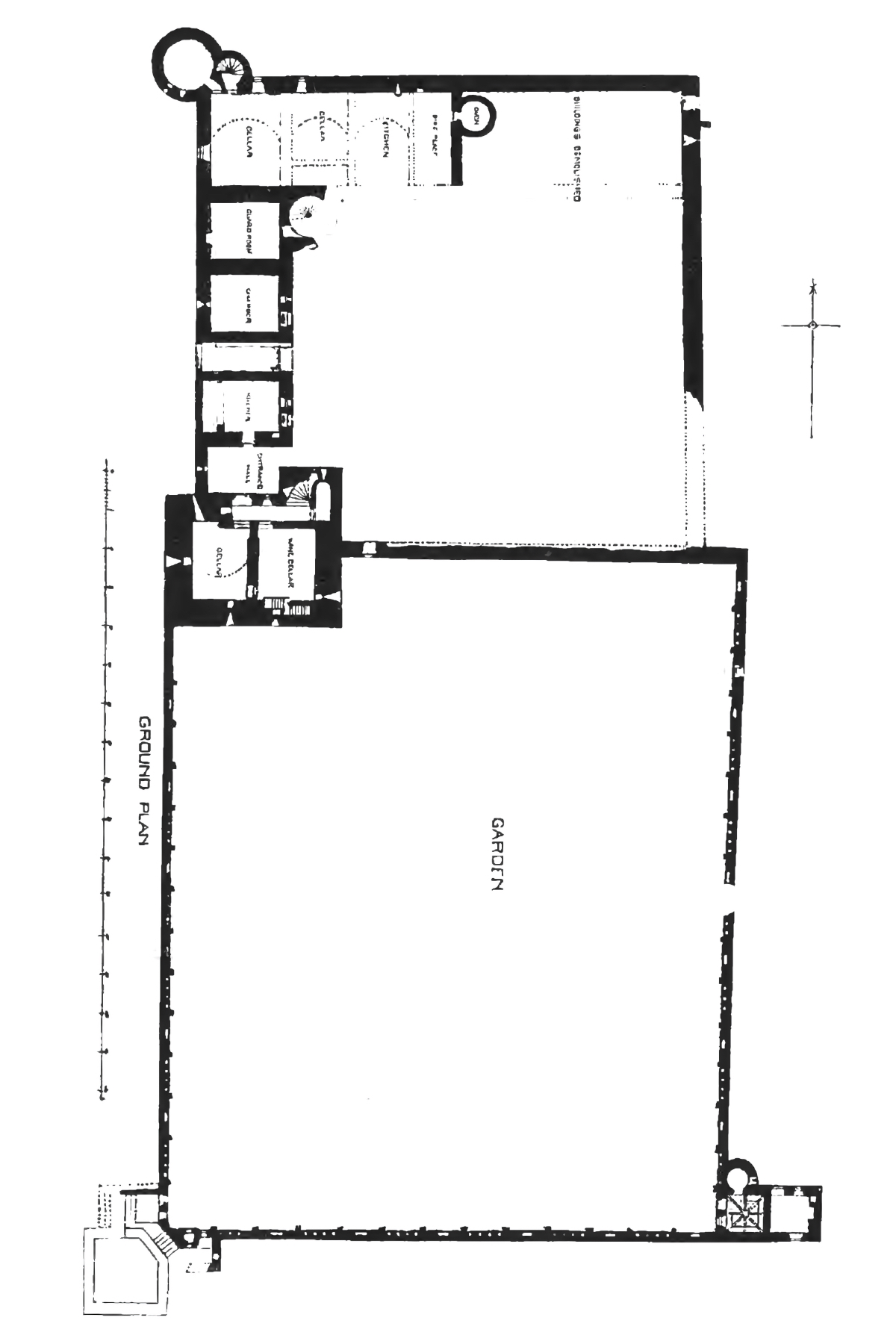

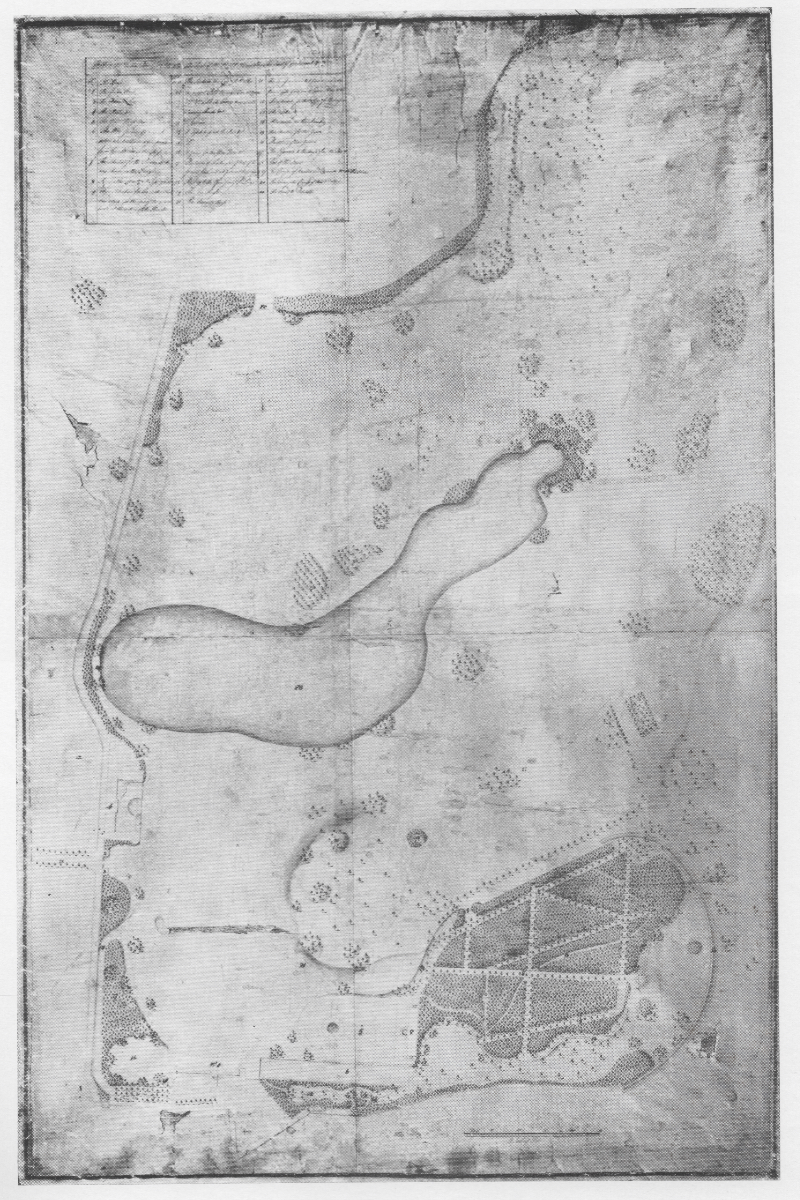

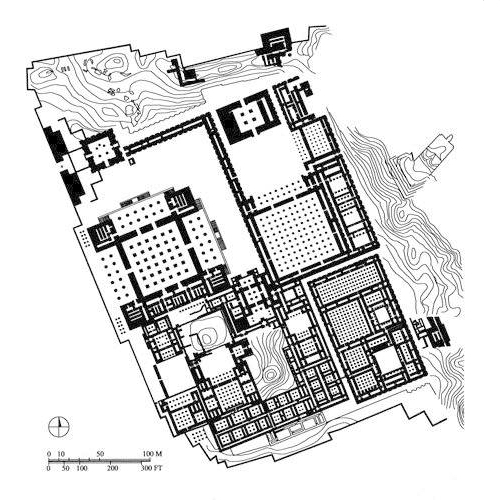

As much as the factory production and conspicuous consumption of cloth, the supply of, and demand for, public space was one of the many consequences of what Eric Hobsbawm called the 'dual revolution' - industrial in Britain, democratic in France - that constituted modernity [2]. The arcades were the first 'public' space in Paris ('public' like public houses or pubs in Britain - actually private spaces), a role later usurped at a grander scale by the boulevards. A look at a map of Paris before the Revolution shows a very different use of urban space: large private gardens for the many hôtel particuliers and royal squares such as the Place des Victoires.

Jean Baptise Michel Jaillot: Table Alphabetique Des Rues de la Ville et Faux-Bourges de Paris 1778

David Rumsey Maps

David Rumsey Maps

roll over for Paris in 1828

The idea of a 'public sphere' was formulated by Jürgen Habermas, who published Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit before, but predicting, the decline of the 'public sphere' at the end of the 20th century [3]. The life span of 'public space' may be symbolised by the rise and fall of couture, from the now unknown flâneurs and flâneuses and Charles Frederick Worth - the sartorial equivalent of Charles Garnier's Opéra - to the great and timeless Cristobal Balenciaga. The decline of public space is a very regrettable and troubling phenomenon - particularly the closure of pubs - as it reflects what Habermas thought of as the replacement of the shared, critical activity of public discourse by a more passive culture consumption [4].

David Harvey, one of the most celebrated theorists of capitalism as 'modern life', and vice-versa, saw Paris as the capital of the 19th century [5]. While Harvey's analyses of modernism and postmodernism make sense, a whole Benjamin industry has sprung up around the arcades. Looking at them now, it is difficult to believe the elaborate social and political theories that have been spun from these humble buildings.

Francois-Jacques Delannoy: Galerie Vivienne, Paris (1823)

photo © Thomas Deckker 1984

photo © Thomas Deckker 1984

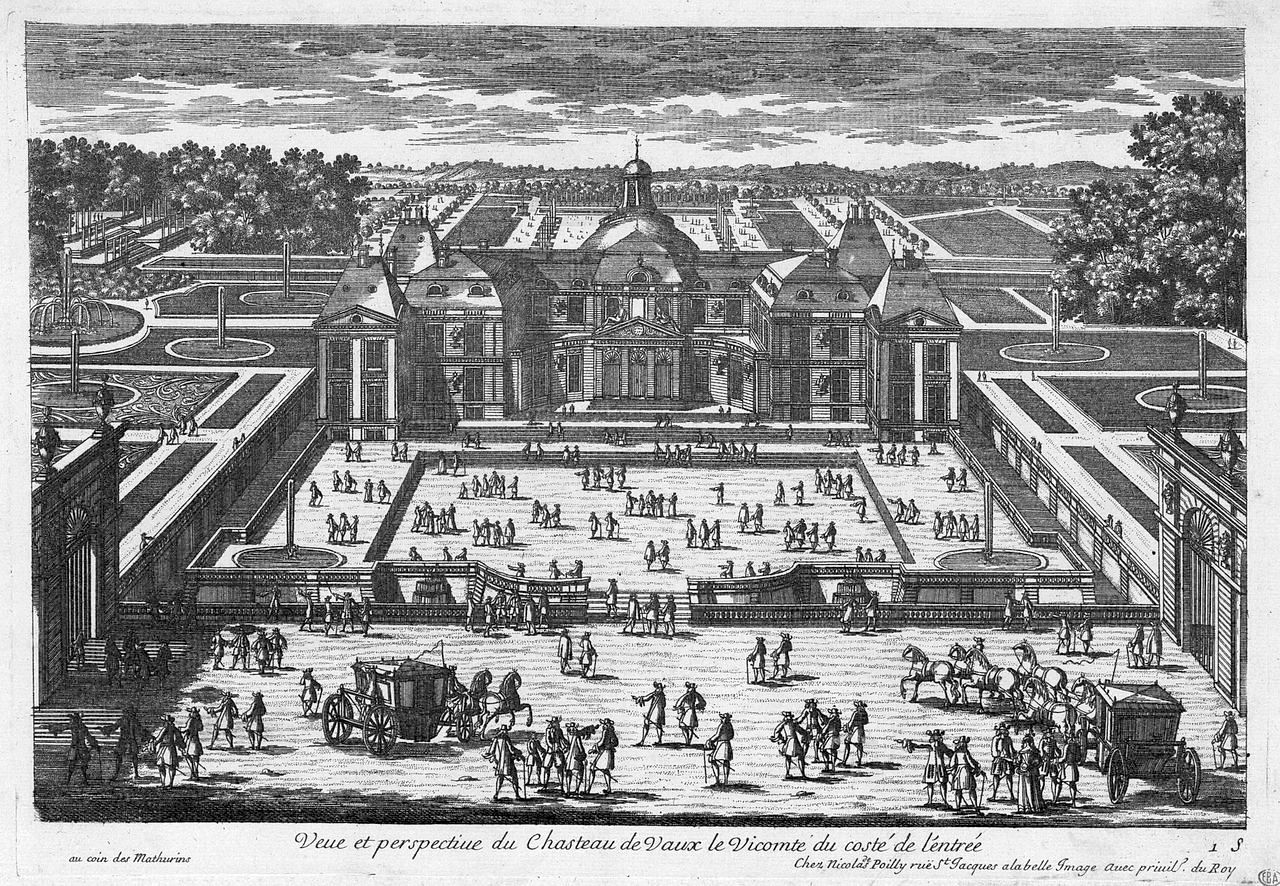

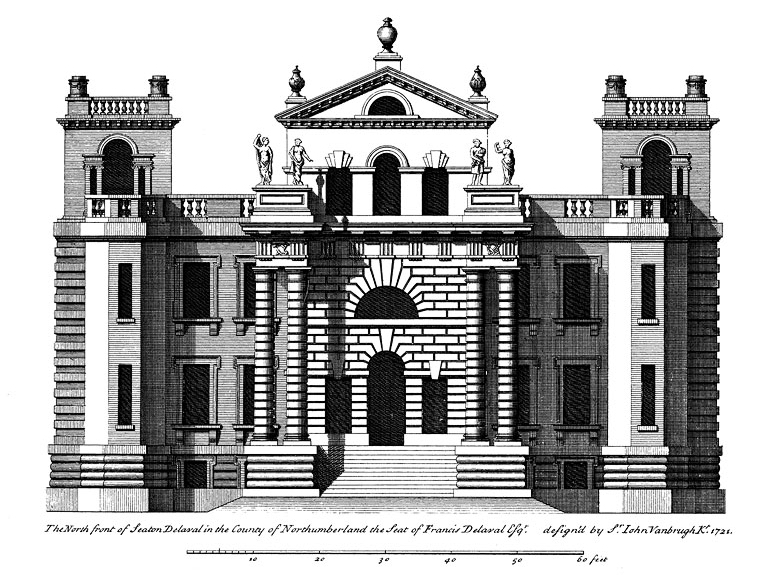

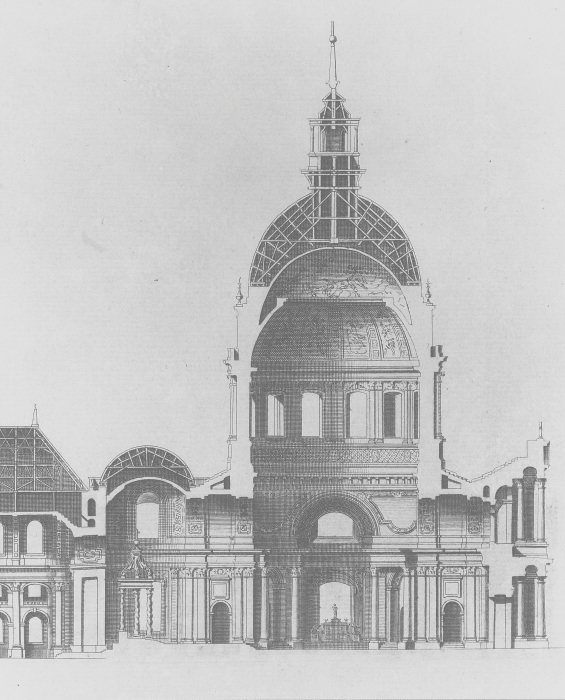

My favourite arcade, for no particular reason, is the Galerie Vivienne. The architect of the Galerie Vivienne, Francois-Jacques Delannoy, won the Prix de Rome as a student at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and spent three years in Rome. Like Labrouste he was an architect of the Bibliotheque Nationale (to which Labrouste added the reading room and book stacks), although he built little and even less remains. The turmoil in France after the Revolution and decades of war was too great an impediment for serious architecture, and the situation did not stabilize until the mid-century with the construction of Labrouste's Bibliothèque Ste Geneviève, and a little later, the transformation of Paris by Baron Haussman.

George Eugene Haussmann: Atlas administratif… de la ville de Paris 1868

David Rumsey Maps

David Rumsey Maps

roll over for location of the Galerie Vivienne and prominent Hausmann projects

I visited the arcades before the great clean-up in Paris, when they were still abandoned and dilapidated, and very atmospheric. Since then they have become fashionable shopping destinations again, and like much of Paris, a bit soulless. The urban transformations of Baron Haussman, the boulevards and department stores that represented and embodied 'modern life' in Paris during the Second Empire, were a spectacle of a different order of magnitude to the arcades and relegated the arcades almost to curiosities. They can be appreciated now for their faded glory and the modest scale of their ambition.

Francois-Jacques Delannoy: Galerie Vivienne, Paris (1823)

photo © Thomas Deckker 1984

photo © Thomas Deckker 1984

What did Paris look like when the arcades were built?

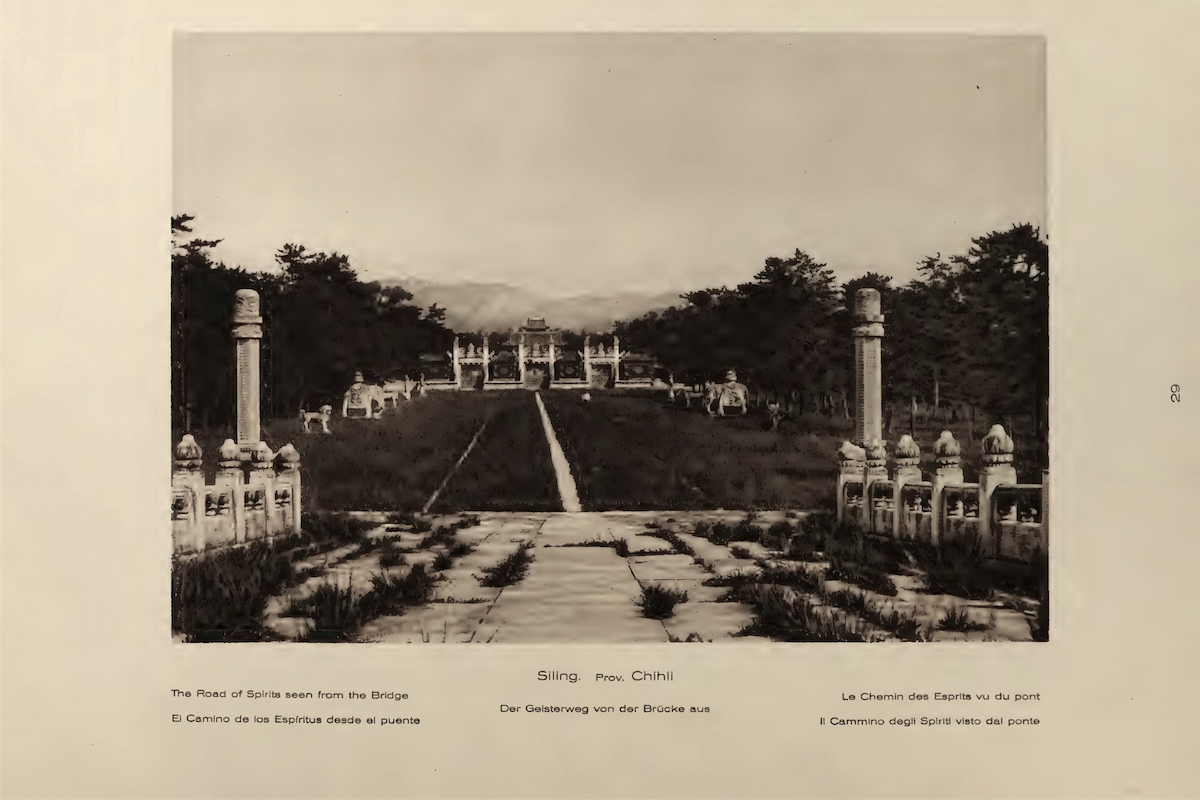

What did Paris look like when the arcades were built? The arcades were built before the practical realisation of photography in the 1850s, which coincided with the urban transformations of Baron Haussman. Contemporary maps show the dense network of small streets, and the lack of public spaces which role the arcades fulfilled. Enough of 'old Paris' was left, however, that the pioneer urban photographer Eugène Atget could record the 'Ancien Regime' in the 1890s and as late as the 1910s; the arcades were likely only slightly removed from their original. His later photographs were contemporary with the birth of Modernism and show what architects of the Modern Movement regarded as chaos, but, to my eyes, looks healthy and robust. His photographs of 'old Paris' were greatly admired by the Surrealists, and by later photographers in Britain (including, of course, Eric de Maré) and the United States.

Eugène Atget: Galerie Vivienne (1906-07)

Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

Eugène Atget: Passage Choiseul (1826-27)

Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

One of Atget's most fervent admirers was Berenice Abbott, the great chronicler of New York City in the 1940s. Abbott met Atget in Paris in 1925, and on his death in 1927 bought his collection and took it to New York City; the Museum of Modern Art, New York subsequently purchased the archive from her in 1968. Atget's collection was thus able to be seen by a new generation of photographers in the United States.

Contemporary Paris was celebrated by artists as well as photographers. The Impressionists, as T. J Clark points out, were chroniclers of 'modern life': recording the transience of public life in the boulevards and guingettes. [6]It is strange that the work of the Impressionists is so highly valued while the urbanism they celebrated so derided.

Camille Pissarro: The Boulevard Montmartre at Night (1897)

National Gallery, London NG4119

National Gallery, London NG4119

Footnotes

1. Walter Benjamin: The Arcades Project [Cambridge, Mass. & London: Harvard University Press 2002; translated by Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin].↩

2.Eric Hobsbawm: The Age of Revolution 1789-1848 [London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson 1962].↩

3.Jürgen Habermas: The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere [MIT and Polity Press 1989; 1st publ. Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit 1962]↩

4. Craig Calhoun (ed): Habermas and the Public Sphere [MIT 1993].↩

5. David Harvey: Paris, Capital of Modernity [New York: Routledge 2003].↩

6. T. J. Clark: The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and His Followers [Princeton University Press 2000].↩

Thomas Deckker

London 2023

London 2023