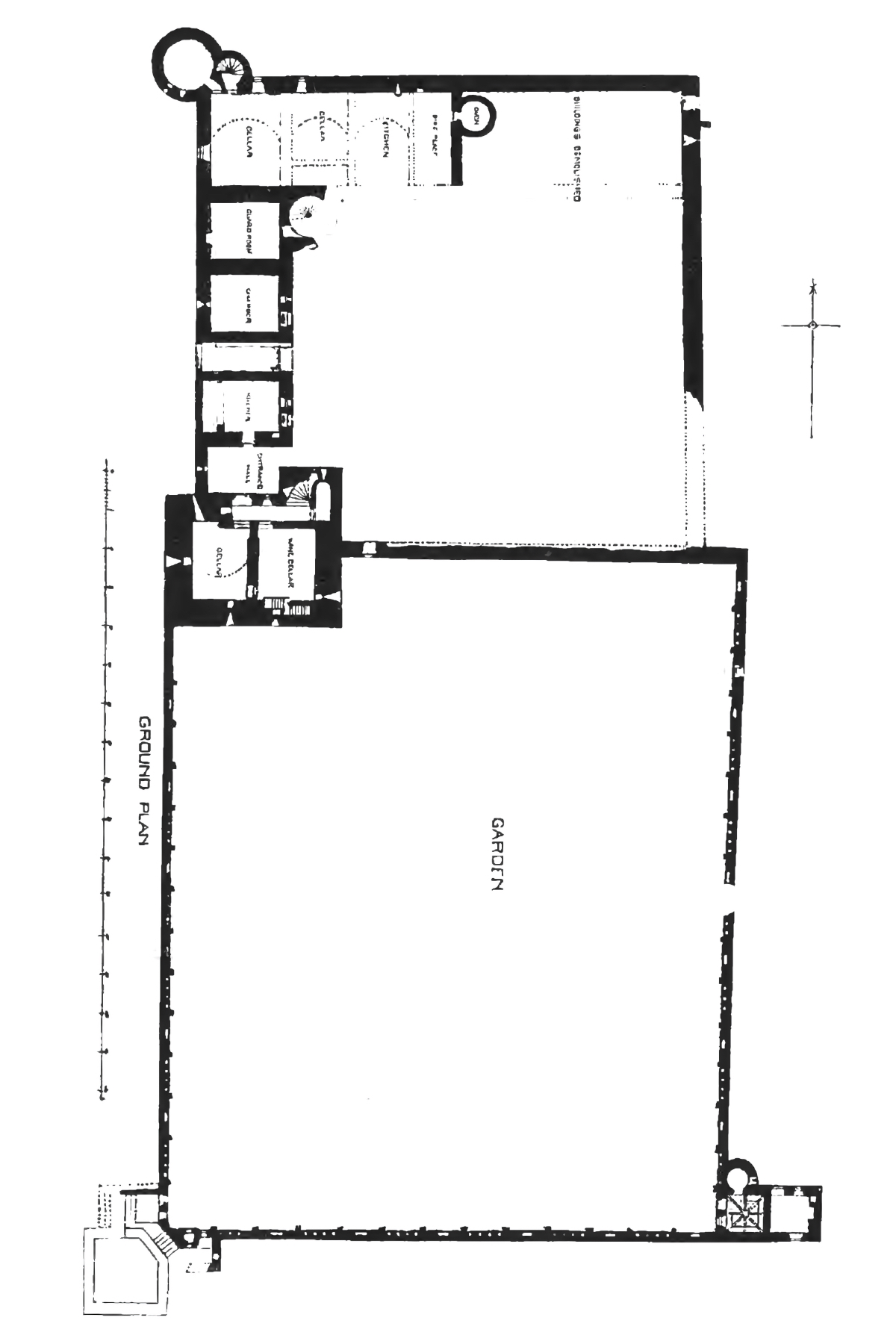

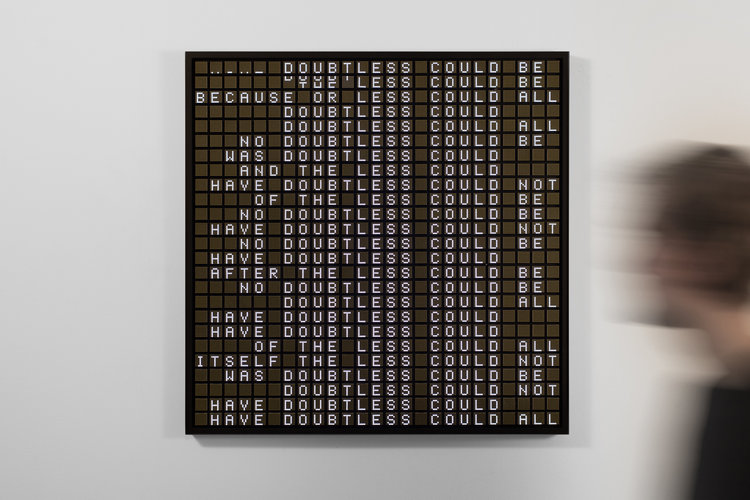

Richard Serra: Weight and Measure 1992

© Tate Gallery

Weight and Measure

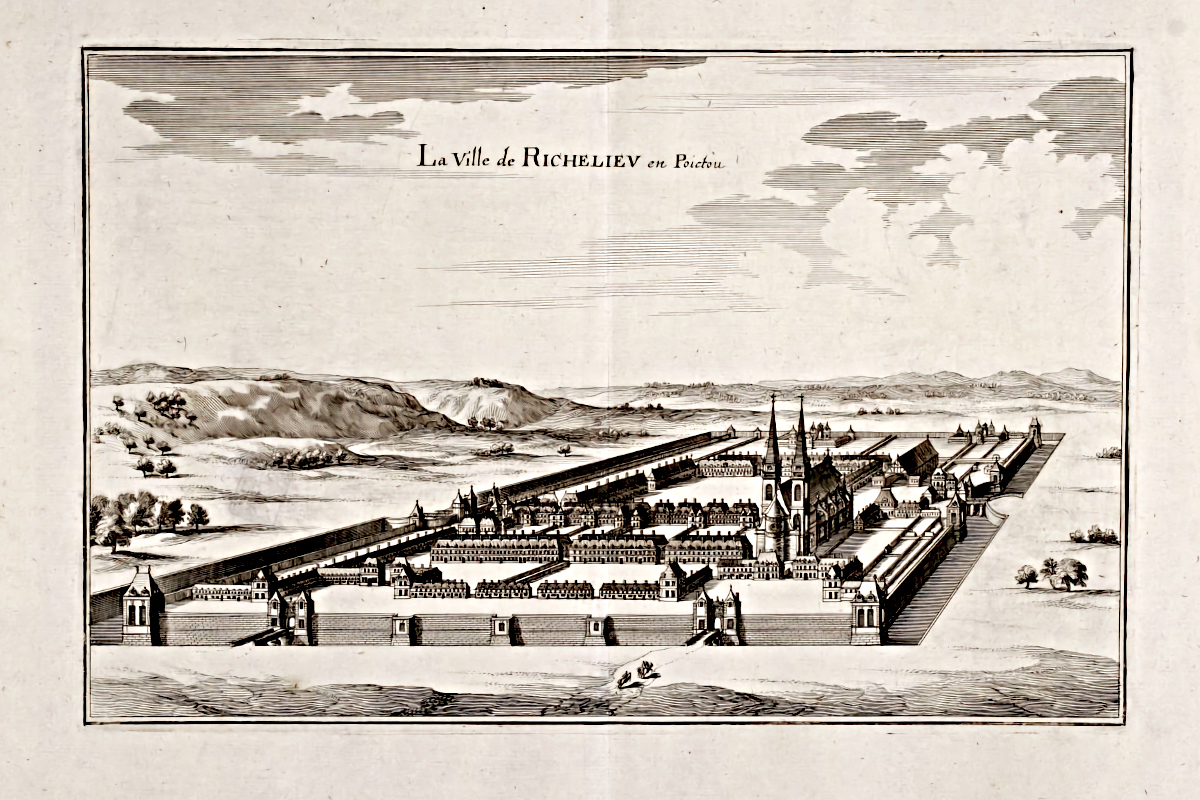

Richard Serra's 'Weight and Measure' exhibition at the

Tate Gallery in 1993 was a turning point in my education as an architect (I was already qualified at that time and registered with the Architects Registation Board but was still developing). I happened to hear Serra speak about his work at the opening of the 'Weight and Measure' exhibition at the Tate and had a moment of epiphany about the relationship of form to context. The ability to organise space among a group of objects and to relate an object to its site is, I believe, a fundamental part of architecture.

Serra told an amusing story that, I believe, distinguishes artists and architects. The solid cast steel objects in 'Weight and Measure' were too heavy for the gallery floors, and the Tate asked him if he could make the objects hollow. He said that he refused, and the Tate subsequently had to reinforce the gallery floors substantially. This attitude seems to distinguish artists and architects, as, in my experience, architects would immediately acquiesce to such a request.

Serra's talk, and his attitude, gave me the confidence to establish a firm direction for my

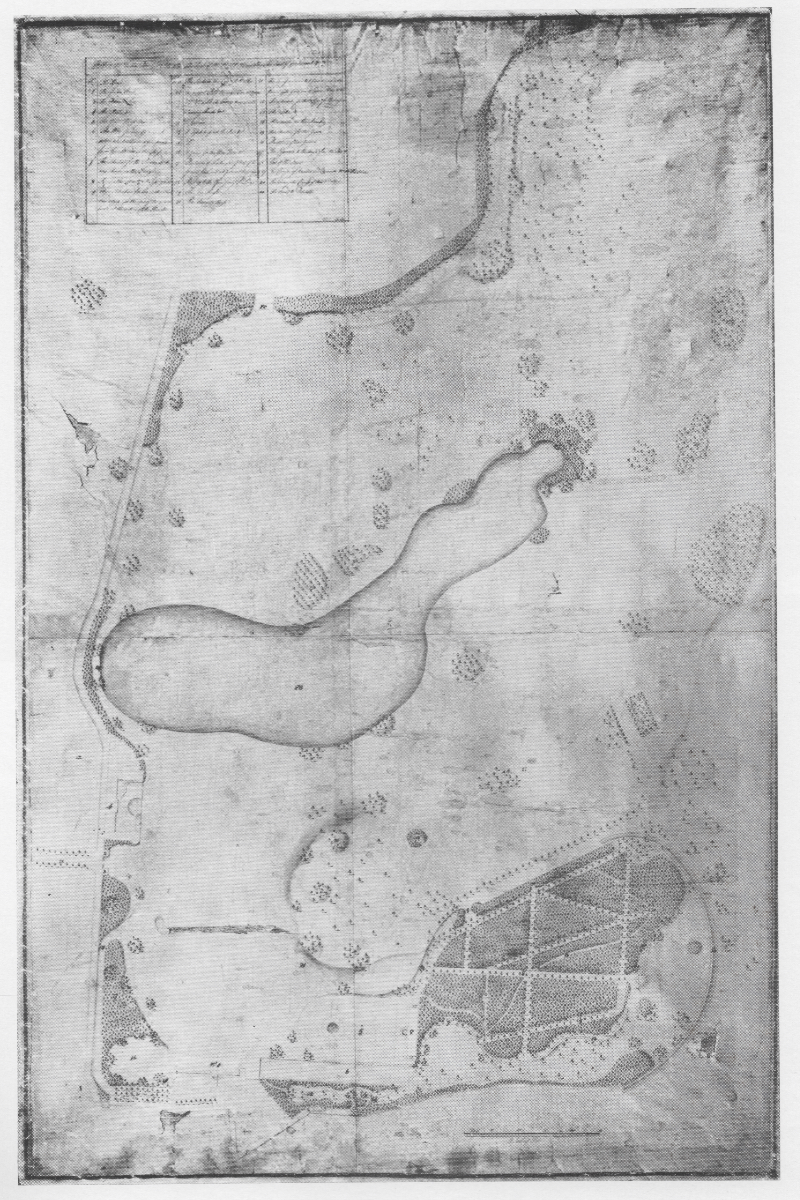

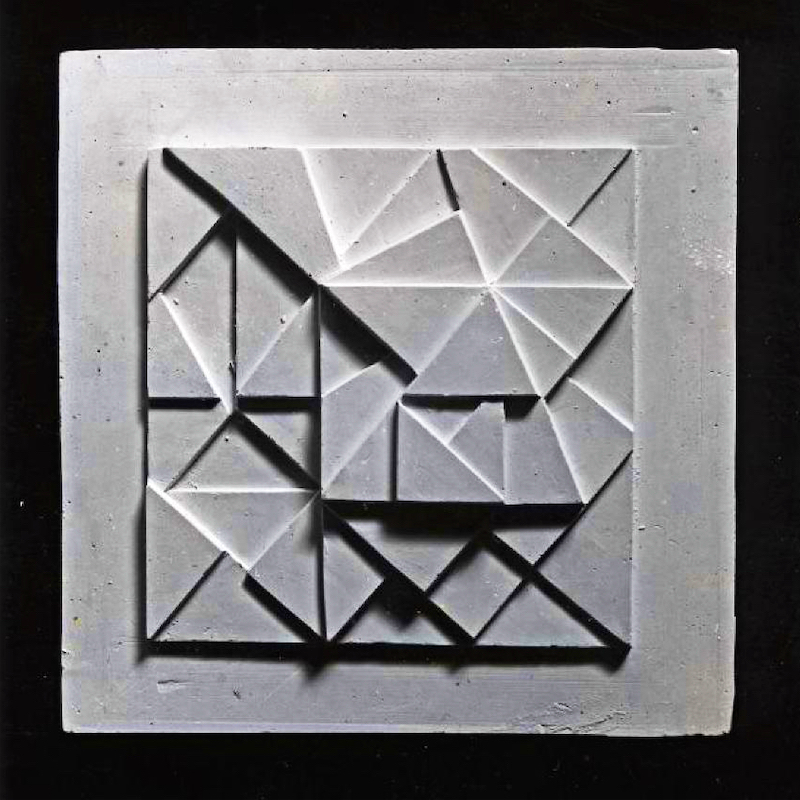

Degree Unit at the University of East London, when we immediately engaged in studies and design projects relating objects to themselves and to their sites, and later in my

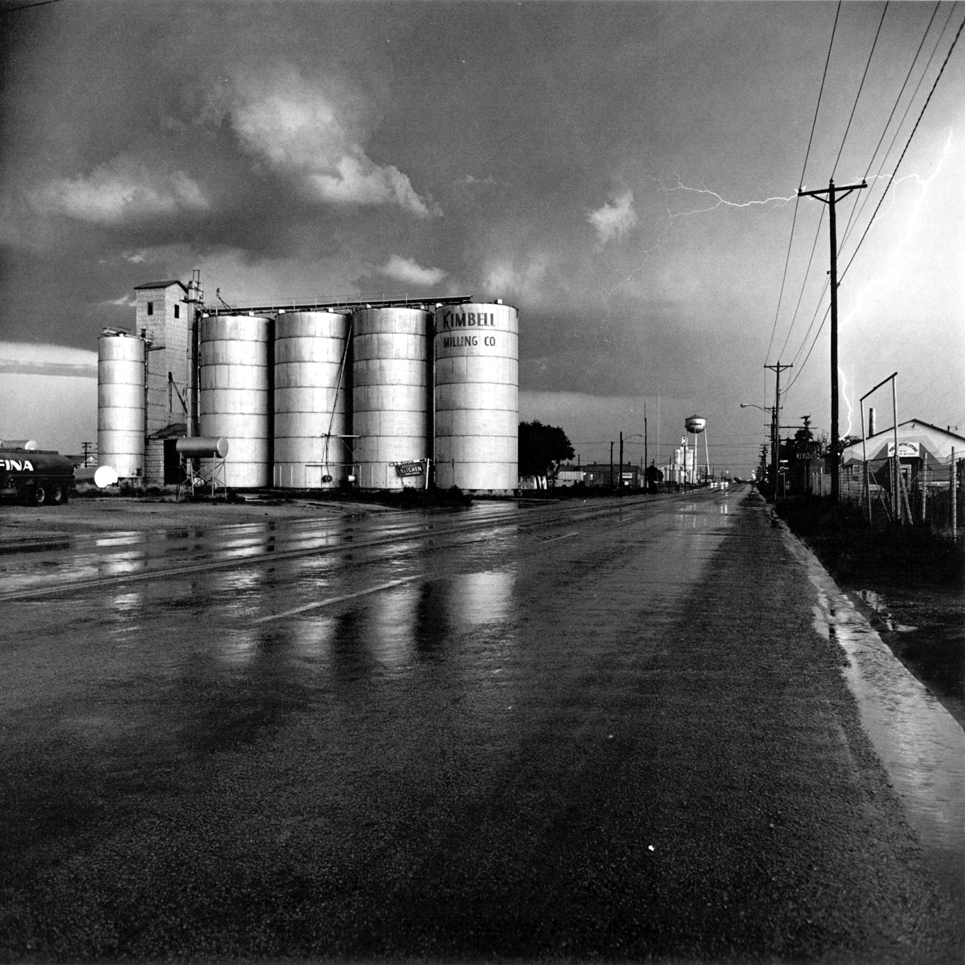

Year 4 Design Research Unit: Landscape:Architecture at the University of Dundee, where, freed from any functional necessities, we happily played with form and space. In fact the aesthetics of form and space can be found in the real world, as I discovered at

Rhodes Welding outside Lamesa, Texas.

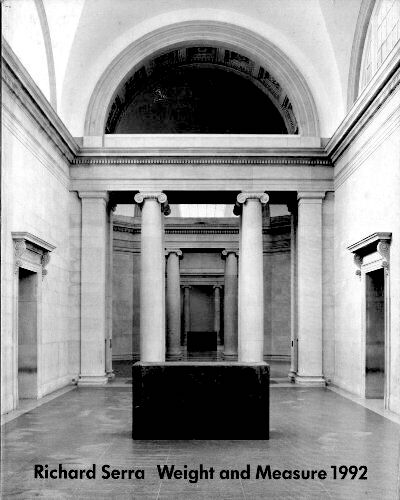

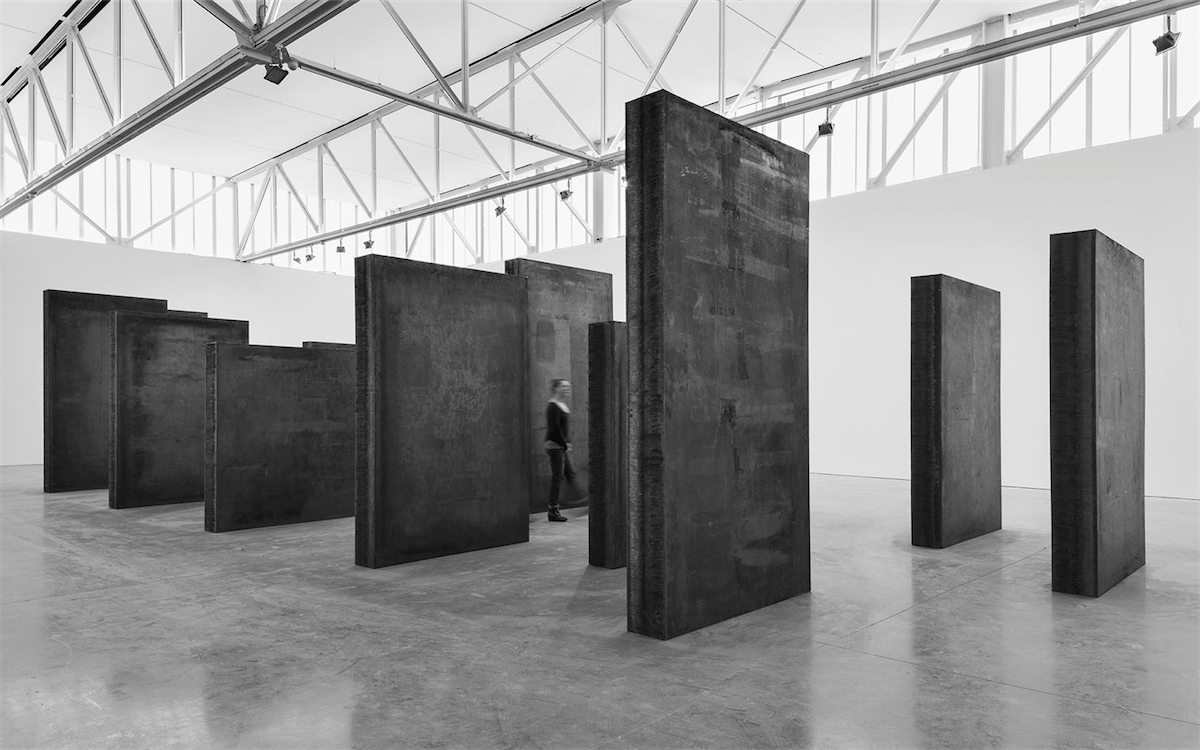

Richard Serra: Every Which Way, 2015

© Richard Serra. Photograph by Christian Mascaro. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery.

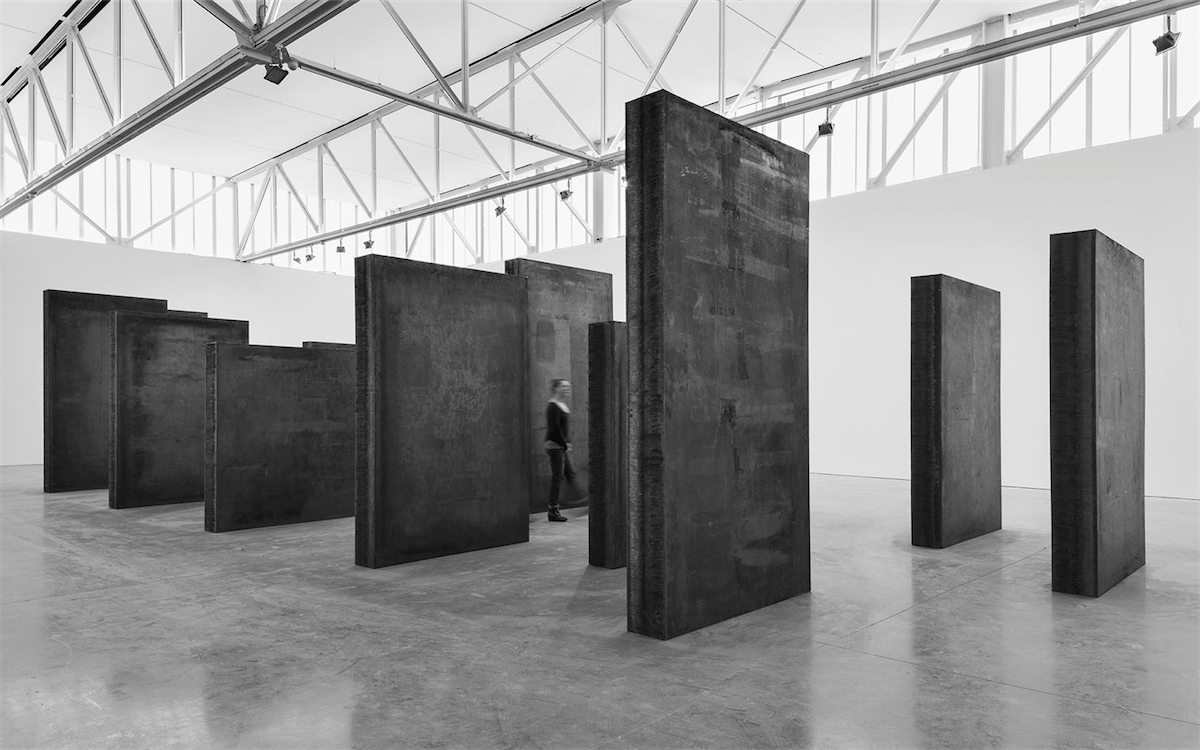

Richard Serra: Through, 2015

© Richard Serra. Photograph by Christian Mascaro. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery.

I appreciate Serra's work as studies of space and form but I know, also, that he is an extremely skilful navigator through, and beneficiary of, the contemporary gallery system. I love seeing Serra's work in galleries, but his public work in urban settings, such as in Broadgate, looks as corporate as the buildings around it. This is doubtless because of what Robert Hughes, in 'On Art and Money', called the 'commodification of the art market':

What is called 'public art' seems absolutely trivial and meaningless in comparison.

Richard Serra: Forged Rounds, 2019

© Richard Serra. Photograph by Christian Mascaro. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery.

Richard Serra exhibits drawings and objects frequently. His work may be see at the

Gagosian Gallery.

Thomas Deckker

London 2020

Update March 2024

Richard Serra throwing lead, for ‘Scatter Piece’ (1967)

from Richard Serra/sculpture [The Museum of Modern Art, New York 1986]

Houston Street, New York City

photo © Thomas Deckker 1990

The warehouse is significant as not only a place to work but as a participant in the work itself. Artists such as diverse as Donald Judd and Bridget Riley began their careers in warehouses and the space shaped their work. It was a privilege of these artists who came to prominence in the 1960s and was a particular moment in time, when a dedicated studio would have been expensive but de-industrialisation had made derelict warehouses cheap. This opportunity would disappear during the 1980s as warehouses themselves became desirable residential property.

Footnotes