thomas

deckker

architect

critical reflections

The Barrière de la Villette: the Sublime and the Beautiful

2022

2022

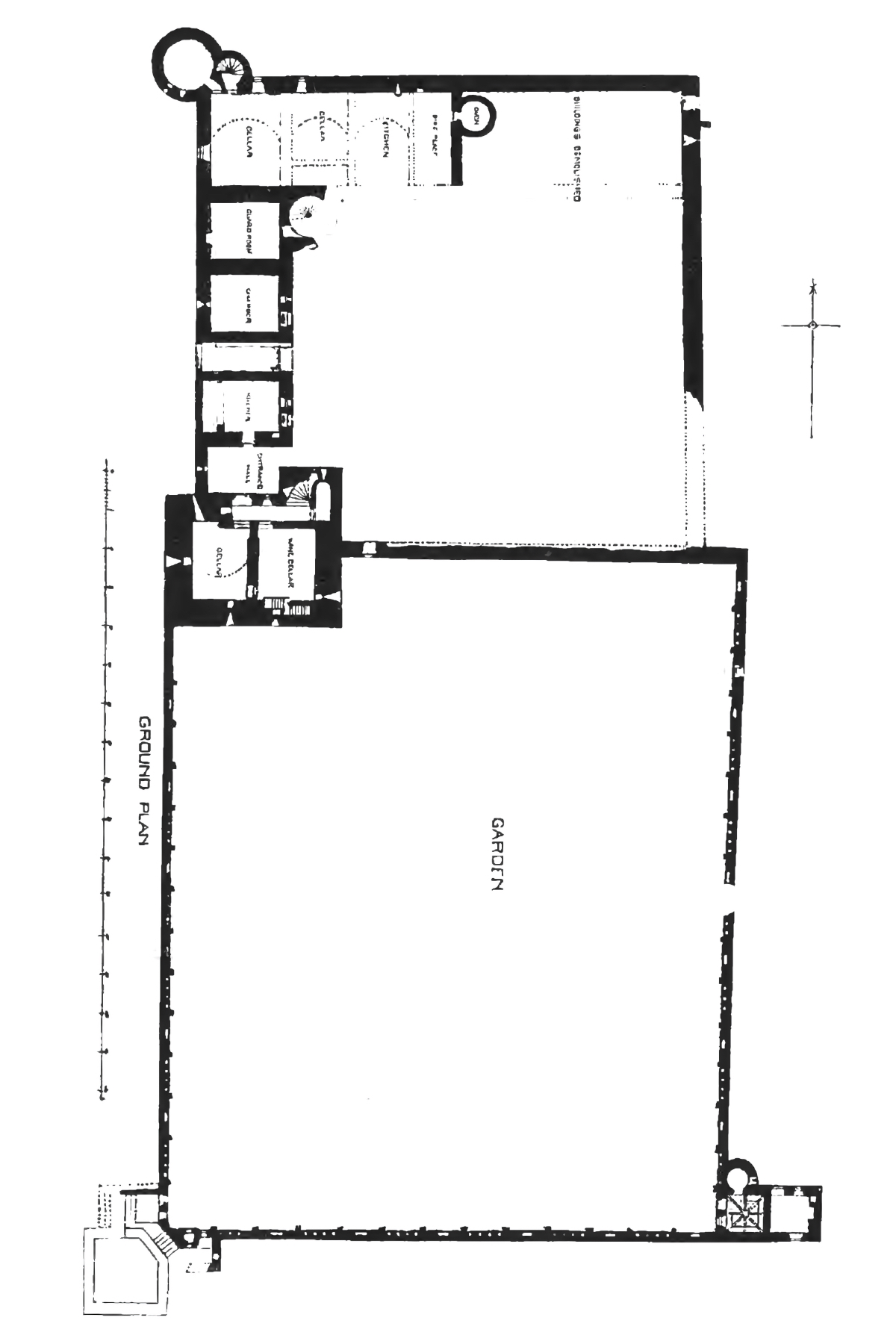

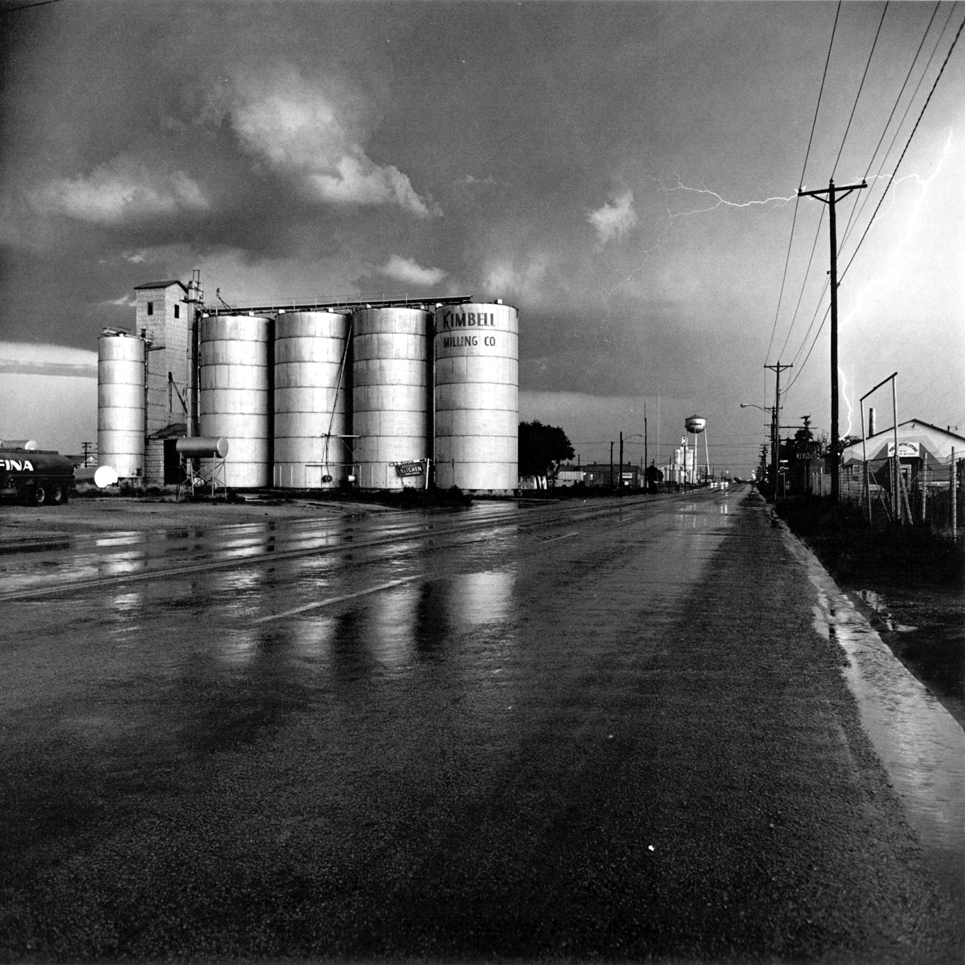

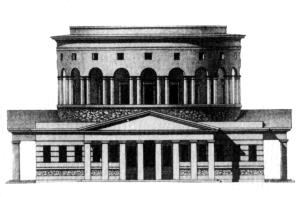

Claude-Nicolas Ledoux: Barrière St Martin, Paris (1785-1790)

from Daniel Ramée: C.N. Ledoux, l'architecture (Paris 1847)

from Daniel Ramée: C.N. Ledoux, l'architecture (Paris 1847)

The Rotonde de la Villette: the Sublime and the Beautiful

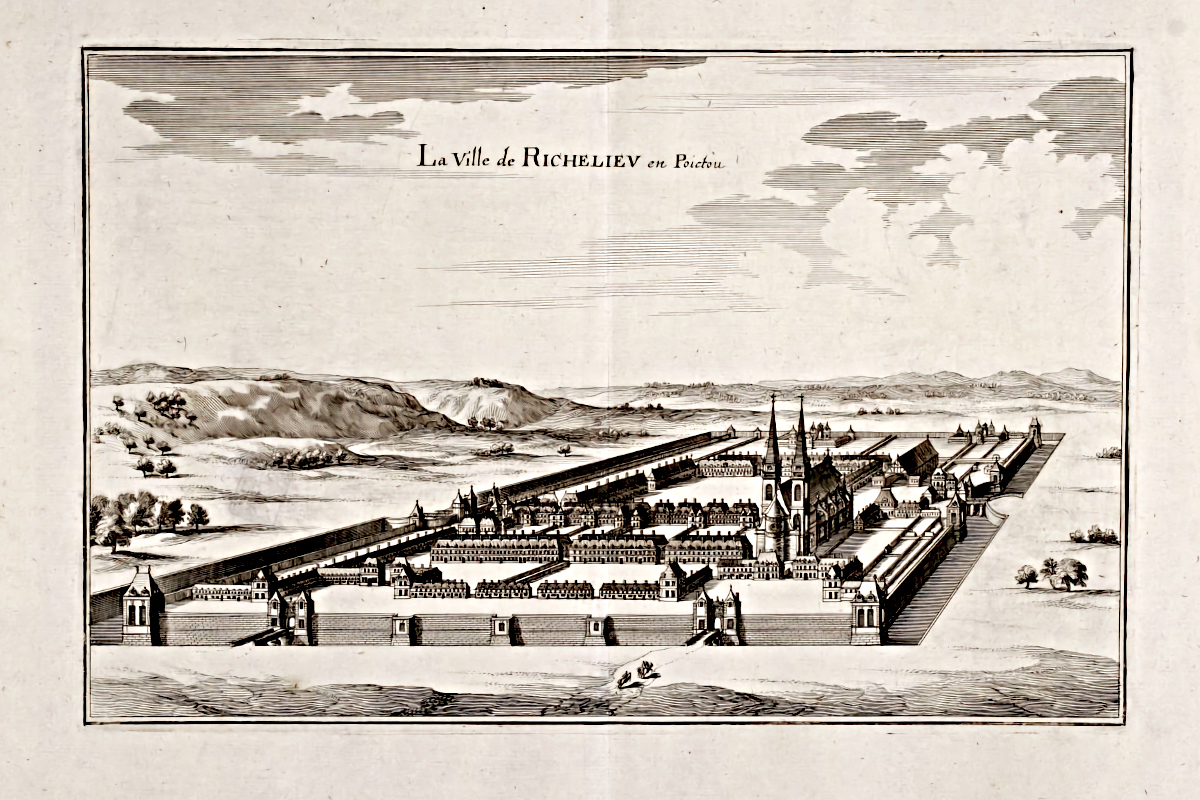

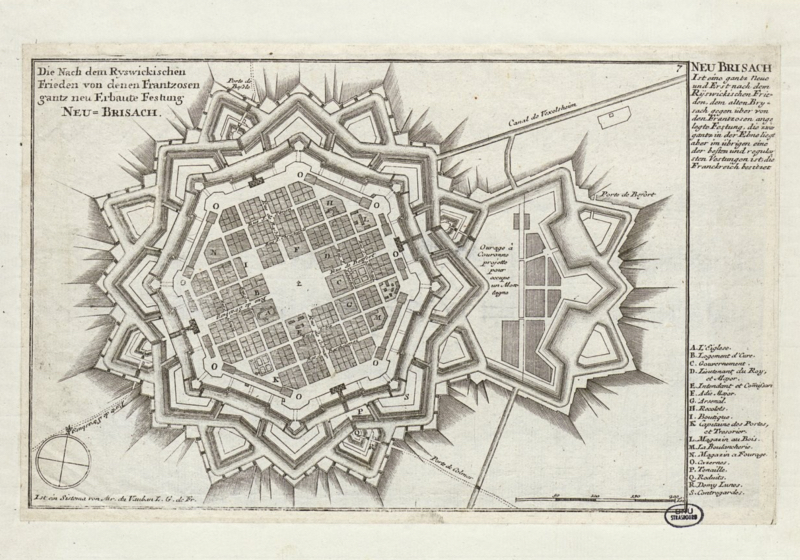

It was a privilege to see Ledoux's Barrière St Martin before its restoration and reinvention as the Rotonde de la Villette. In its dirty and unused condition it was closer to its original appearance and feeling as a working building. The Barrière St Martin was originally part of a chain of walls and gates constructed in 1784 as a customs barrier to the city of Paris. The construction of the customs barrier, which raised the price of food and wine dramatically for citizens in Paris to the benefit of the Ferme Générale, a small group of tax officials, was one of the causes of the Revolution: the walls and gates were sacked and burned in 1789, 4 days before the fall of the Bastille.

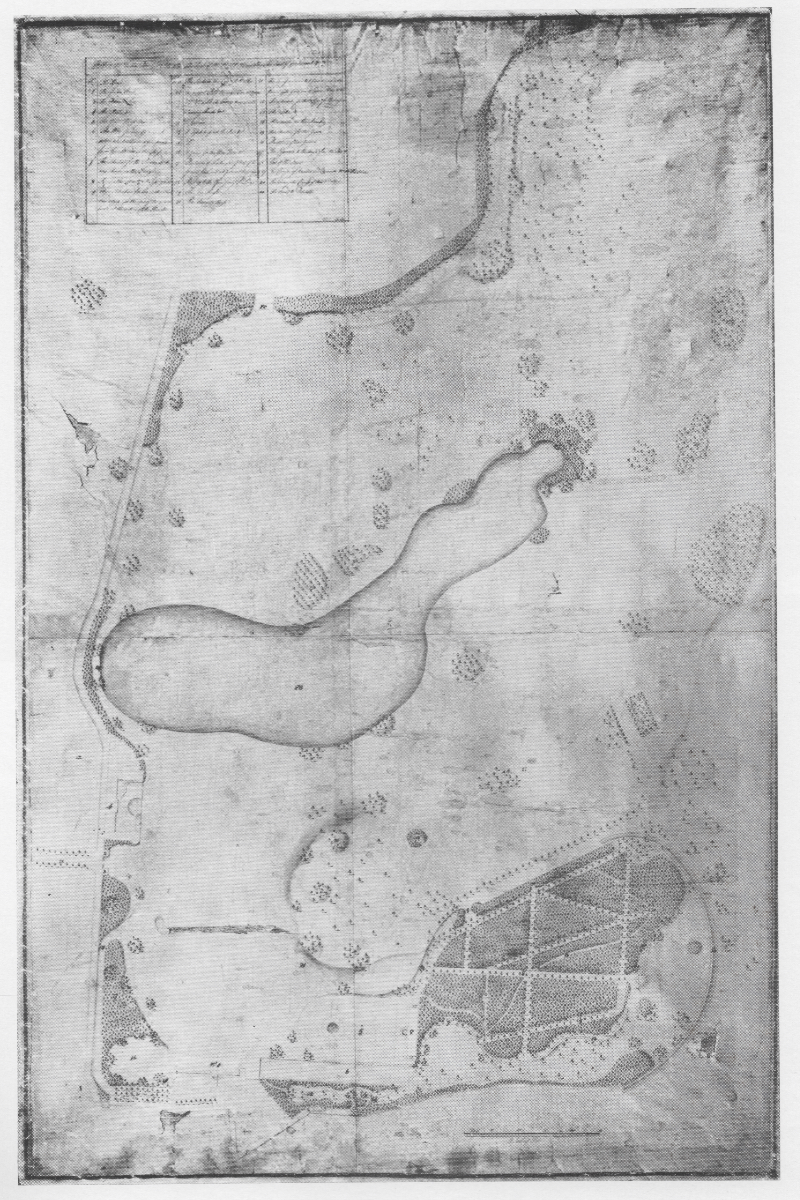

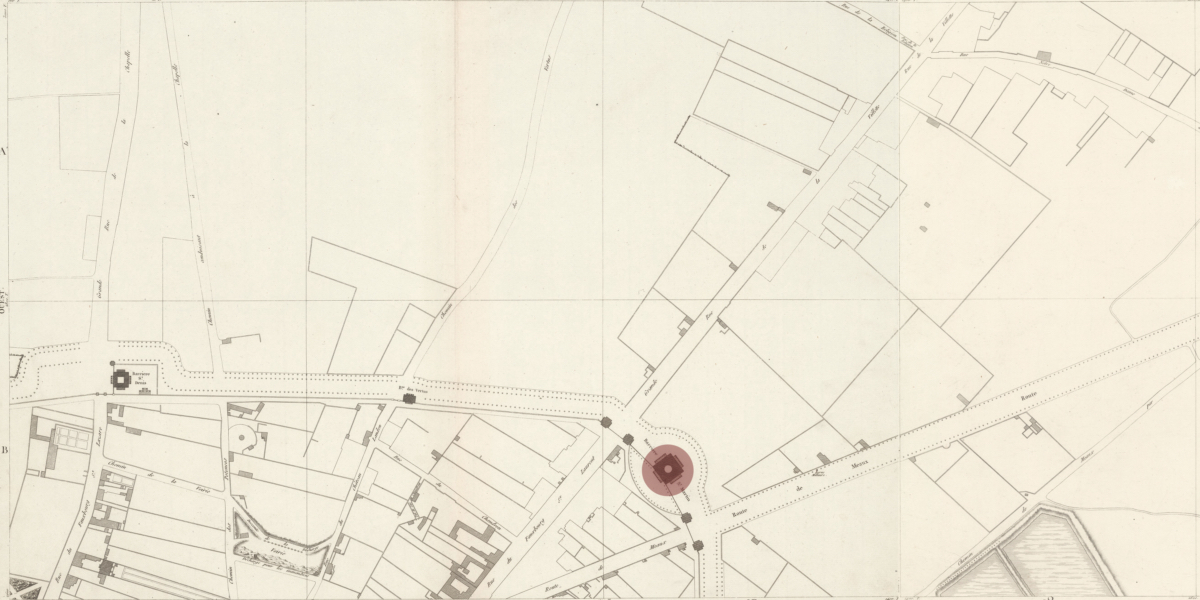

Plate XIII from Edme Verniquet: Atlas Du Plan General De La Ville Paris (Paris 1795)

Gallica / Bibliothèque nationale de France

Gallica / Bibliothèque nationale de France

roll over for illustration of the Basin de la Villette from George Eugene Haussmann: Atlas administratif… de la ville de Paris 1868

David Rumsey Maps

David Rumsey Maps

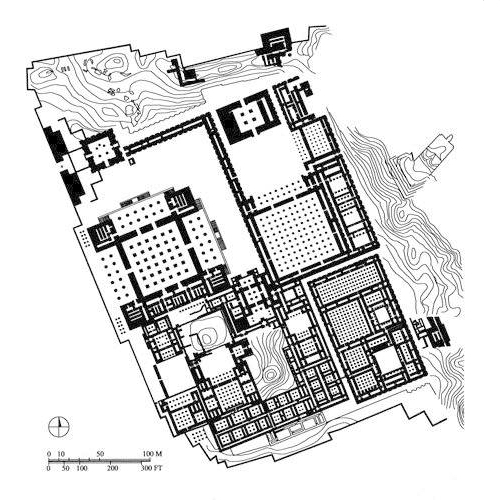

The map by Edme Verniquet shows the extraordinarily high standard of mapmaking at the end of the 18th century. The Barrière de la Villette is marked with a red circle. It is one of very few features identifiable on Haussmann's map of 1868.

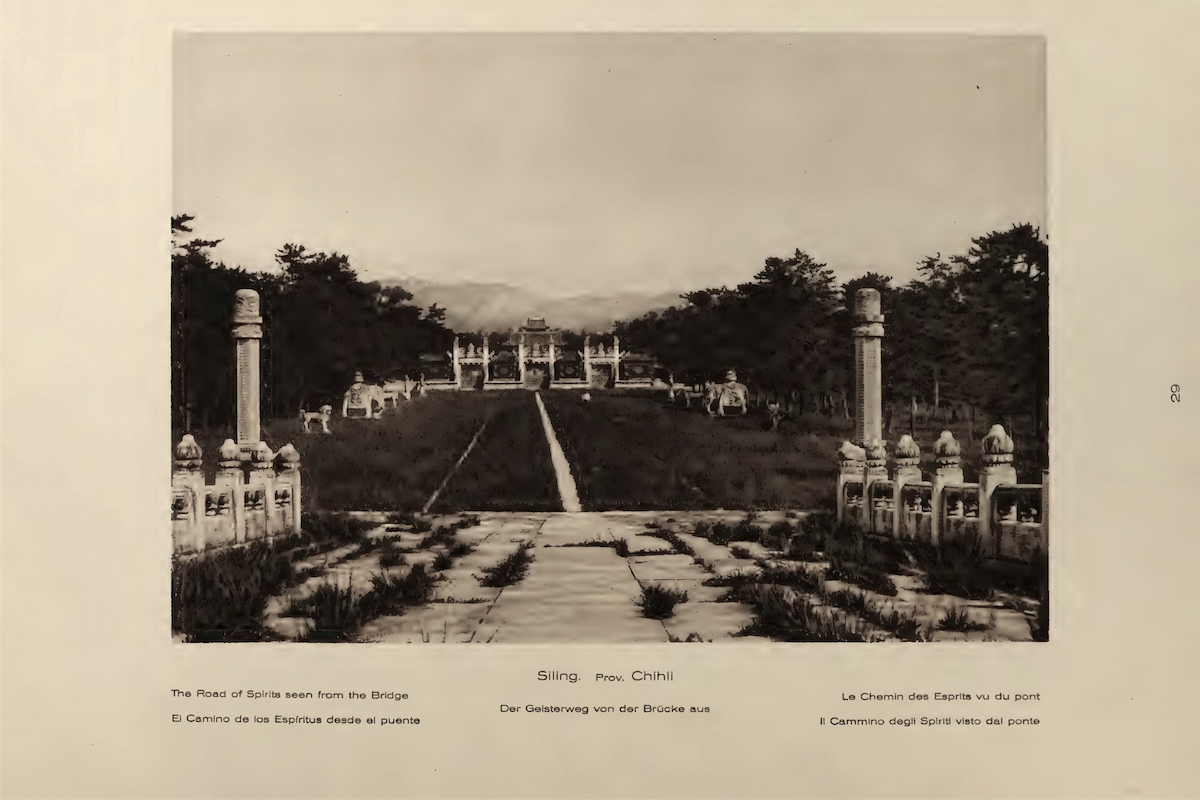

Haussmann's new boulevards erased the sites of most of the barrières by building roads along the spaces left by the demolition of the wall. The Barrière St Martin survived probably because its surroundings changed. In 1808, just over 20 years after construction started, its siting changed from a gate to fields to the dramatic focal point of the Bassin de la Villette, an enormous canal basin commissioned by Napoleon as the termination of the Canal d'Ourcq. This was one of several urban improvements and embellishments instigated by Napoleon before his deposition and exile in 1815. In 2009 the building was cleaned and floodlit and the site cleared of car parking. The Rotonde de la Villette rightly appears as a great and treasured building of the Ancien Régime. It is now seen as a beautiful building - but was the Barrière St Martin beautiful?

Claude-Nicolas Ledoux: Barrière St Martin, Paris (1785-1790)

© Thomas Deckker 1984

© Thomas Deckker 1984

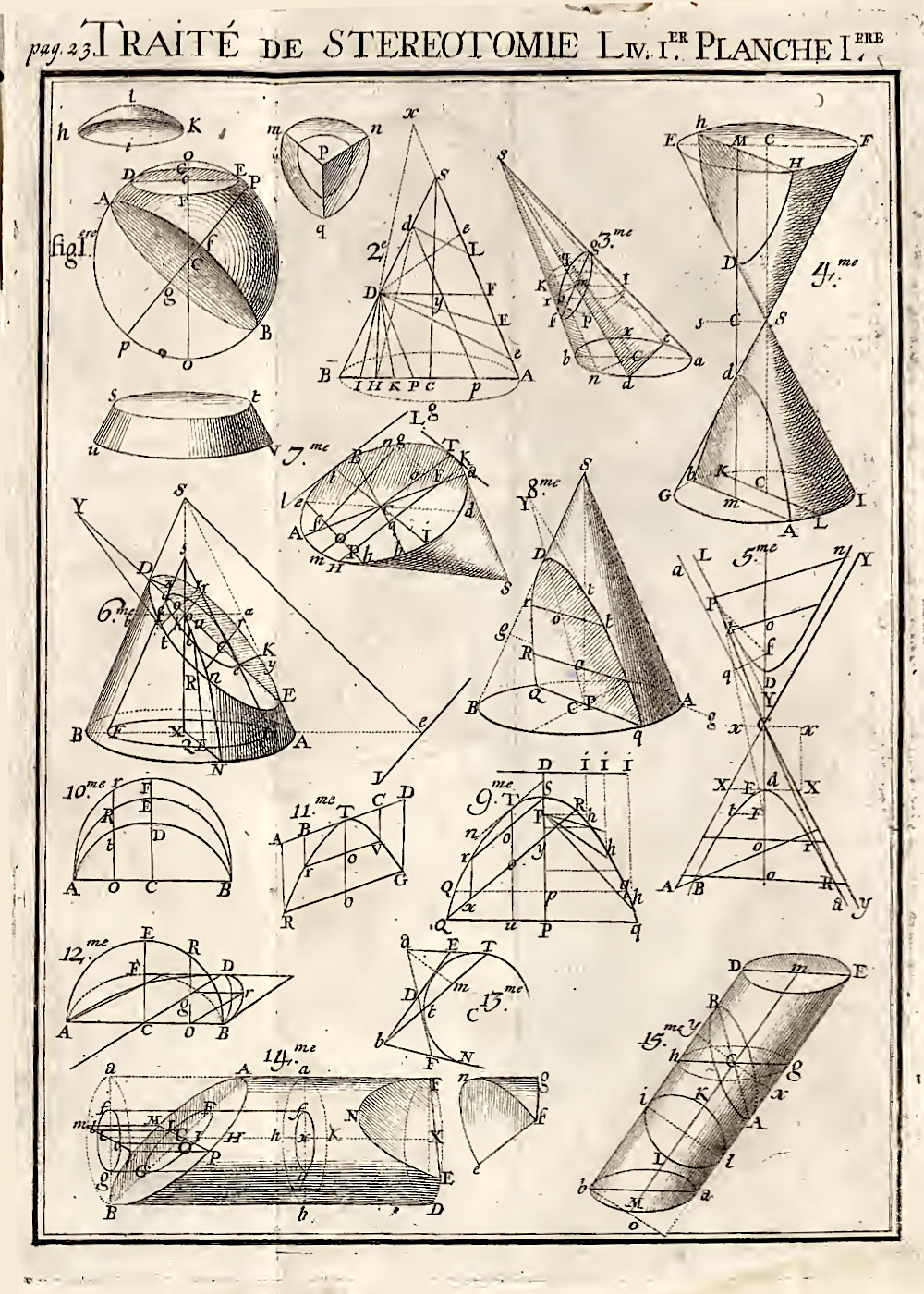

The Barrière St Martin was seen by Ledoux and his circle of admirers and detractors not as beautiful but as sublime. The sublime was a reaction against the pursuit of beauty at the end of the 18th century. The English philosopher Edmund Burke, in the Philosophical Enquiry into the Origins of Our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful (1756), identified the aesthetic response of the sublime as more powerful and direct than pleasure, which he believed, was derived largely from 'association', conventional ideas rather than direct experience. The adoption of these principles by architects, notably Étienne-Louis Boullée (1728-99) and Claude-Nicolas Ledoux (1736-1806), overturned the conception of a carefully modulated and hierarchical structure and the coherence of form and content in classical architecture.

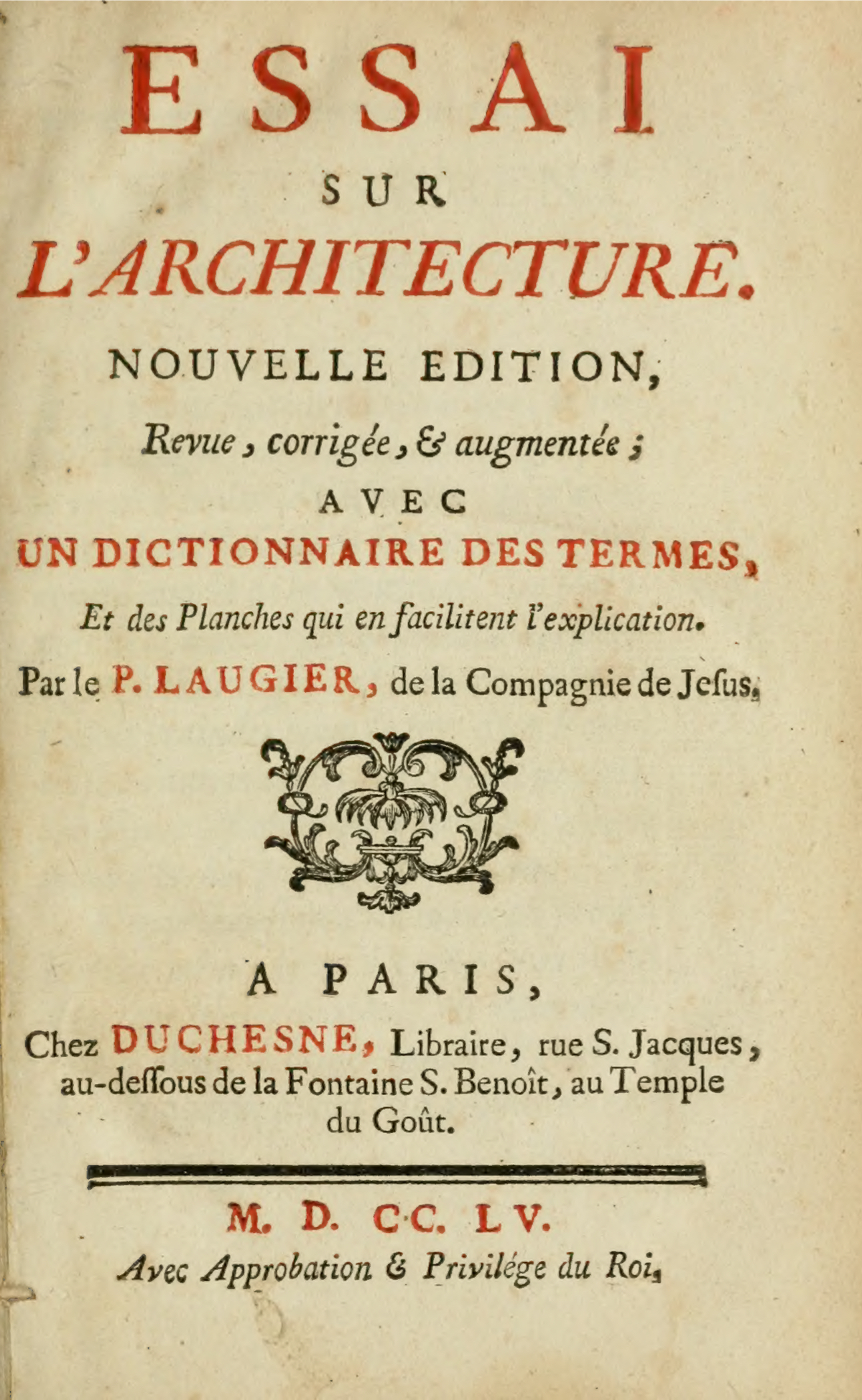

Marc-Antoine Laugier: Essai sur l'Architecture (Paris 1755)

Laugier's Essai, on the 'primitive hut' and the origin of the orders, was one vision of the future of classicism in the 1750s. Laugier based the 'primitive hut' on Vitruvius's description of the birth of architecture. Its severe rationality directly inspired architects of the period such as Jacques-Germain Soufflot, whose Church of Sainte-Geneviève, Paris (1757 onwards, now the Panthéon) signalled a return to the first principles of classical architecture. The frontispiece did not follow Laugier's text exactly; it was an allegory of Architecture turning away from Renaissance innovations to what was supposed to be its Ancient origins. Published anonymously in 1753, it was reissued in French and English under his name in 1755.

Laugier's Essai, on the 'primitive hut' and the origin of the orders, was one vision of the future of classicism in the 1750s. Laugier based the 'primitive hut' on Vitruvius's description of the birth of architecture. Its severe rationality directly inspired architects of the period such as Jacques-Germain Soufflot, whose Church of Sainte-Geneviève, Paris (1757 onwards, now the Panthéon) signalled a return to the first principles of classical architecture. The frontispiece did not follow Laugier's text exactly; it was an allegory of Architecture turning away from Renaissance innovations to what was supposed to be its Ancient origins. Published anonymously in 1753, it was reissued in French and English under his name in 1755.

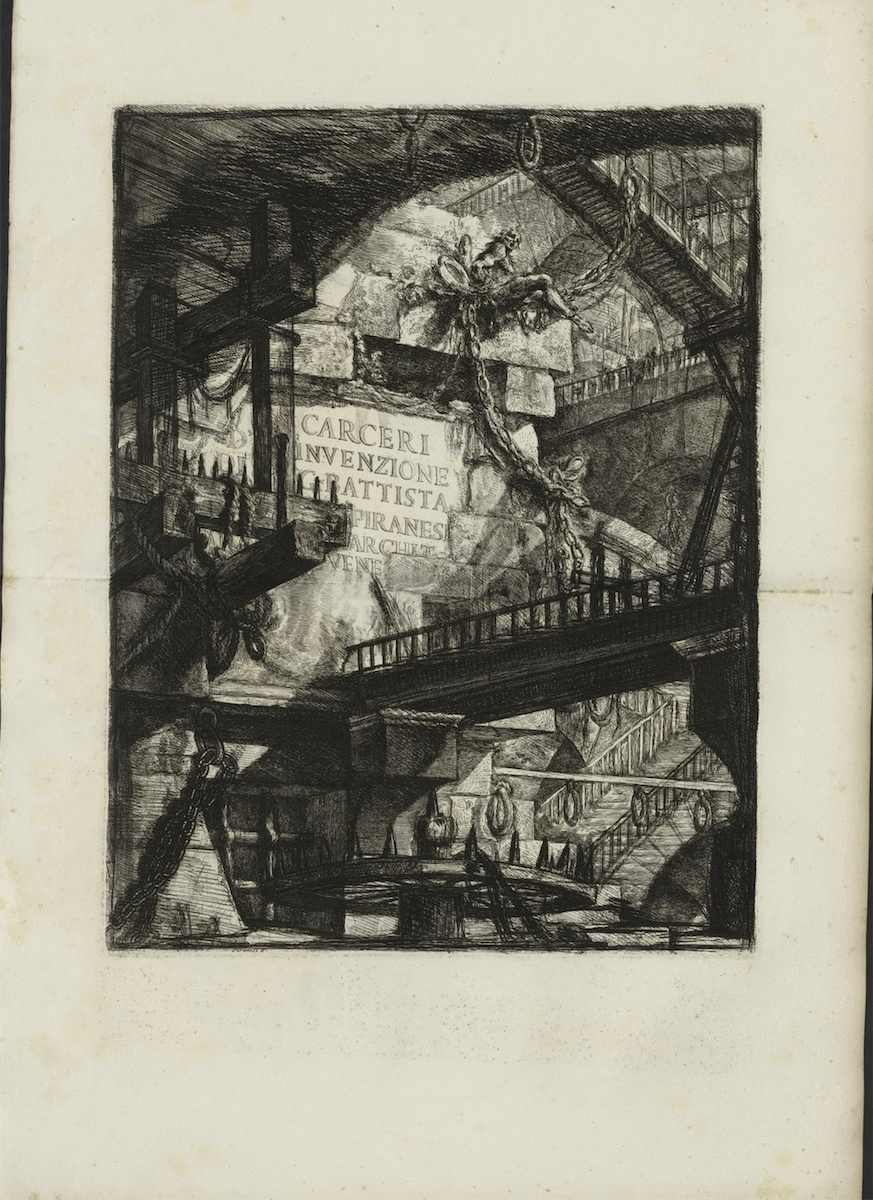

Piranesi: Le Carceri d'Invenzione (Rome 1750)

Piranesi's Imaginary Prisons brought forward a new sensibility in architecture: of vast distances, gloomy interiors and large repeated structures. The feelings of horror these aroused were thought more natural than the pleasure from beauty. Prisons were seen as the archetypal sublime building. Published anonymously in 1750, Le Carceri d'Invenzione was reissued under his name in 1761.

Piranesi's Imaginary Prisons brought forward a new sensibility in architecture: of vast distances, gloomy interiors and large repeated structures. The feelings of horror these aroused were thought more natural than the pleasure from beauty. Prisons were seen as the archetypal sublime building. Published anonymously in 1750, Le Carceri d'Invenzione was reissued under his name in 1761.

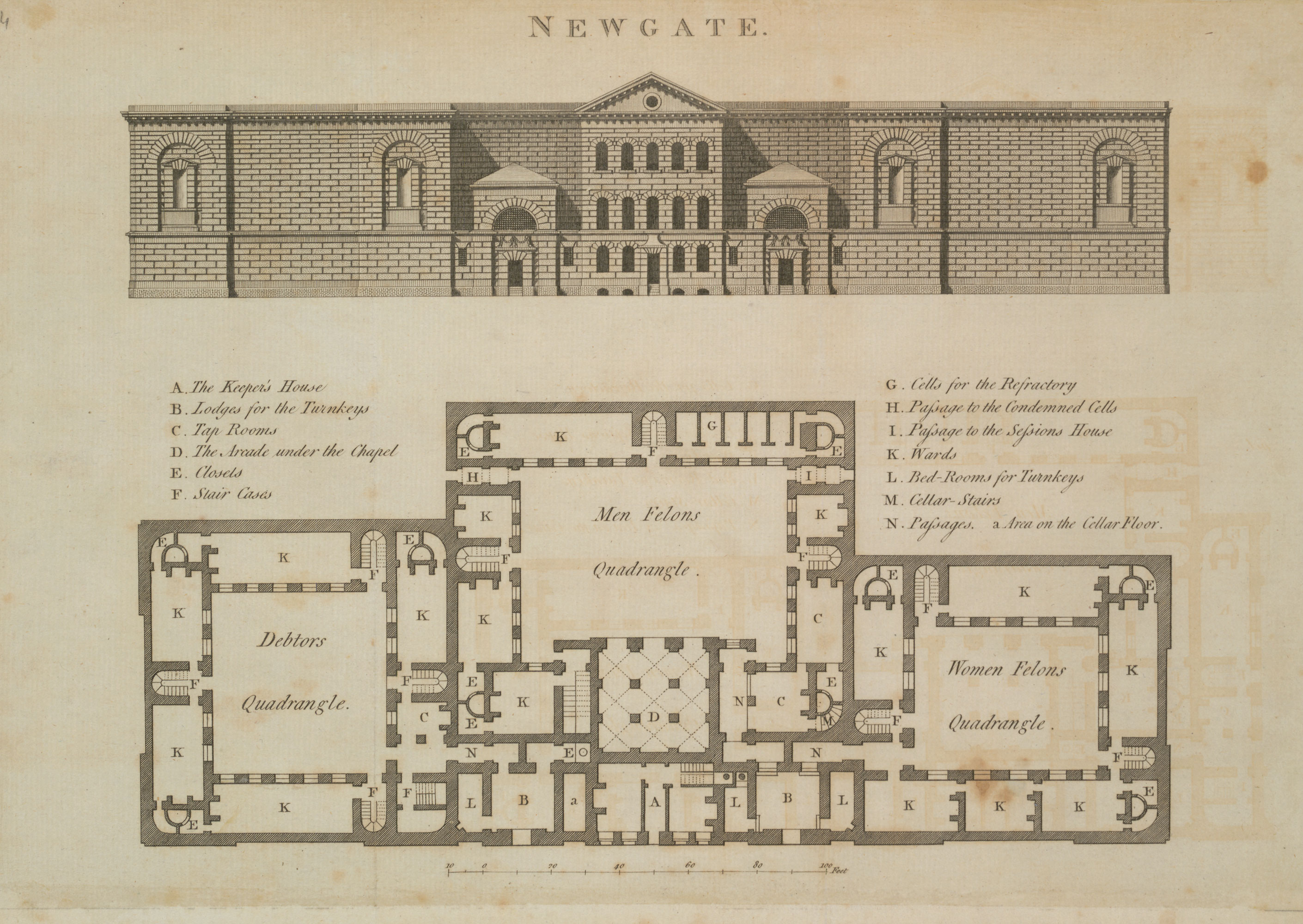

In London at the same time the architect George Dance the Younger designed an iconic building of the sublime, admired even by Ledoux: Newgate Gaol, begun in 1770. Dance had studied in Rome during the 1760s, being admitted to the Accademia de San Luca, and becoming a friend of Piranesi. The emotions of horror aroused by the building were in keeping with the popular feeling that incarceration should be harrowing and degrading. Despite what should have been its popular appeal on these grounds it was sacked and burned during the Gordon Riots in 1780 and not completed until 1782. Conditions inside were notoriously terrible; it was rebuilt as a Victorian penitentiary in 1858, closed in 1902 and demolished in 1904. By a strange coincidence Dance also planned the West India Docks - only slightly larger than the Bassin de la Villette - and their warehouses in 1799, although the warehouses were actually built in a less advanced design by another architect. It would have been a vindication of the sublime to see almost a mile of warehouses under a smoky London sky by an architect of the stature of Dance.

George Dance the Younger: Newgate Gaol, London (1770-1782)

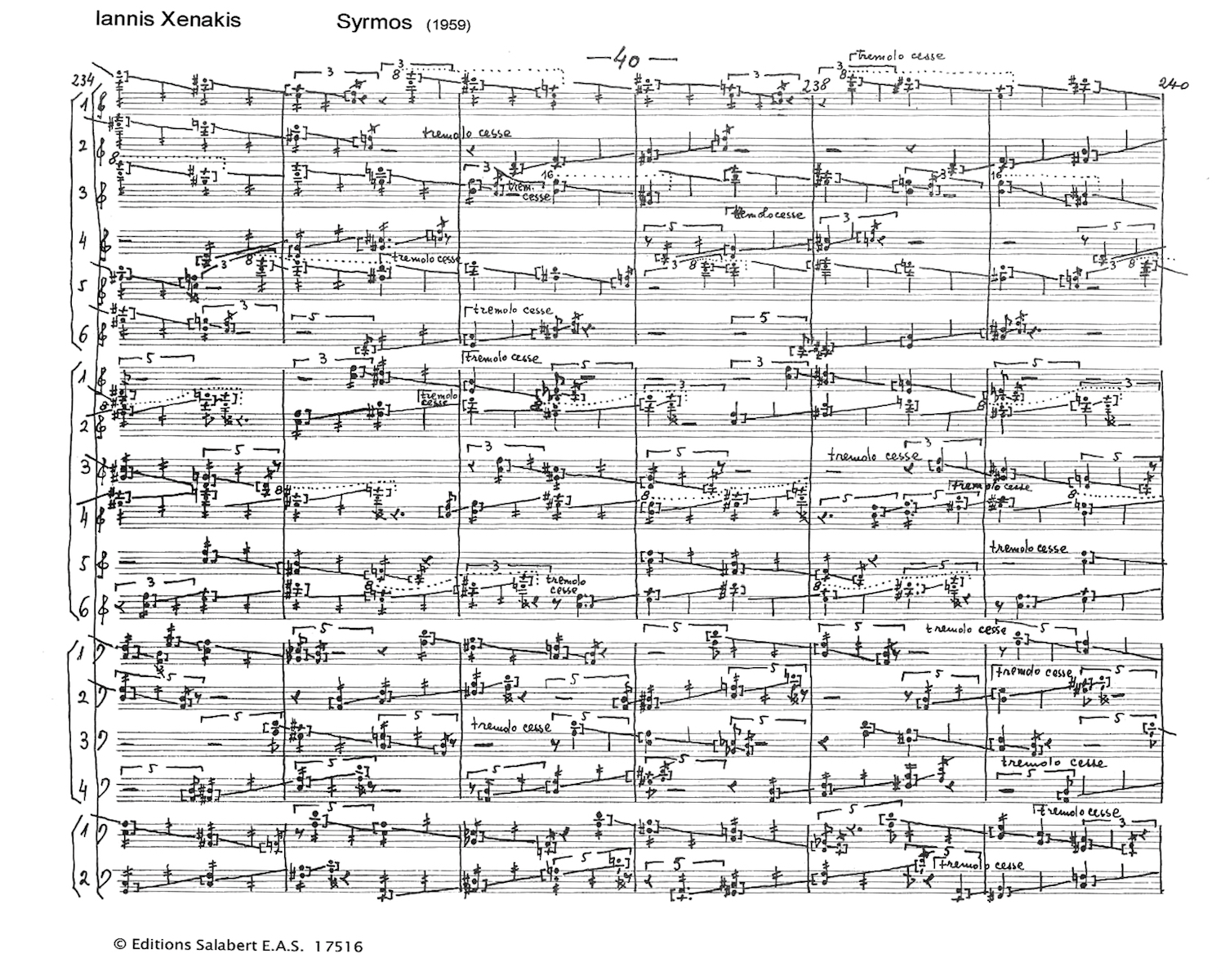

The sublime was not limited to architecture, of course. It had famous literary equivalents such as Frankenstein (1818) by Mary Shelley. Perhaps the most obvious transition from the beautiful to the sublime was in music.

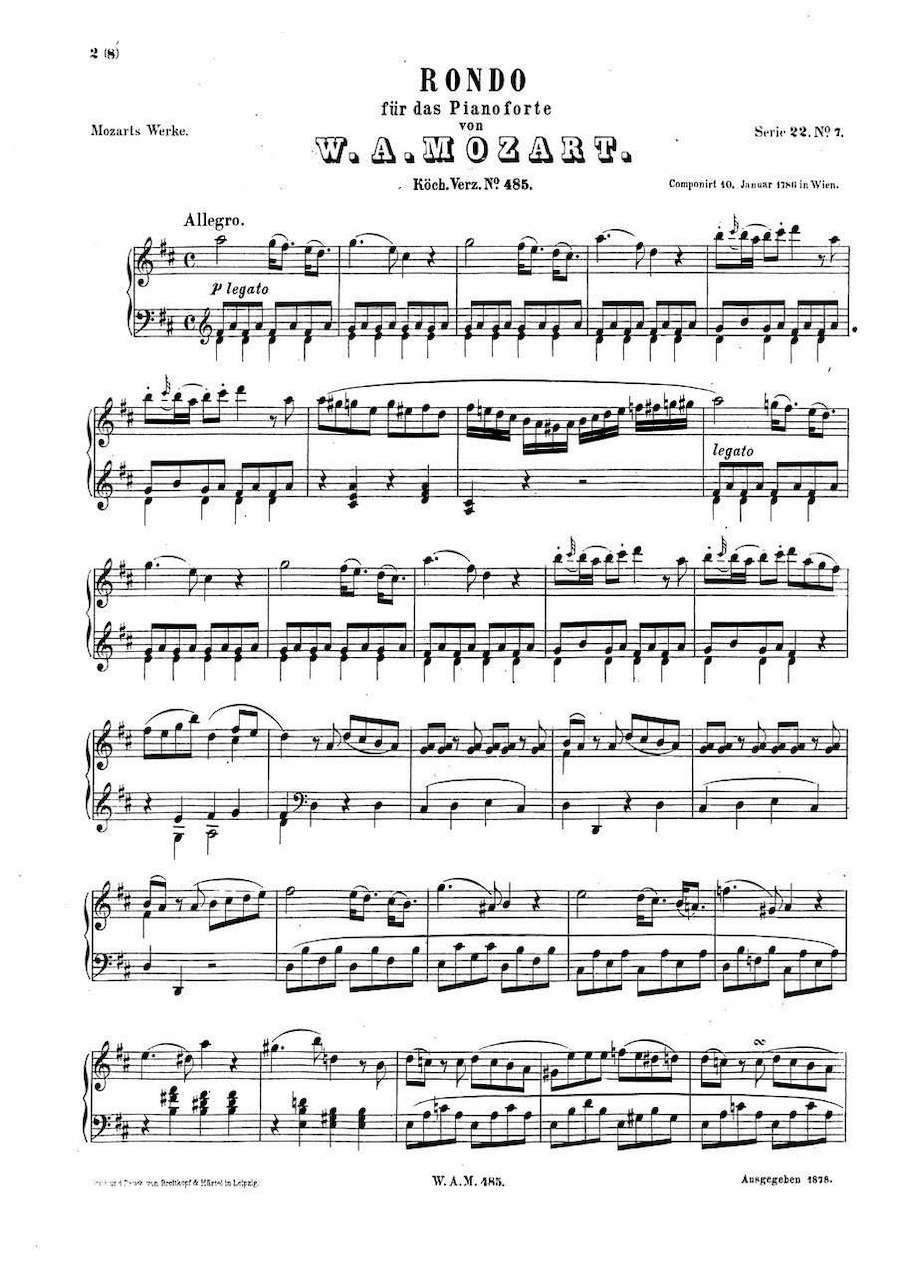

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Score for Rondo in D Major, K485 (1786)

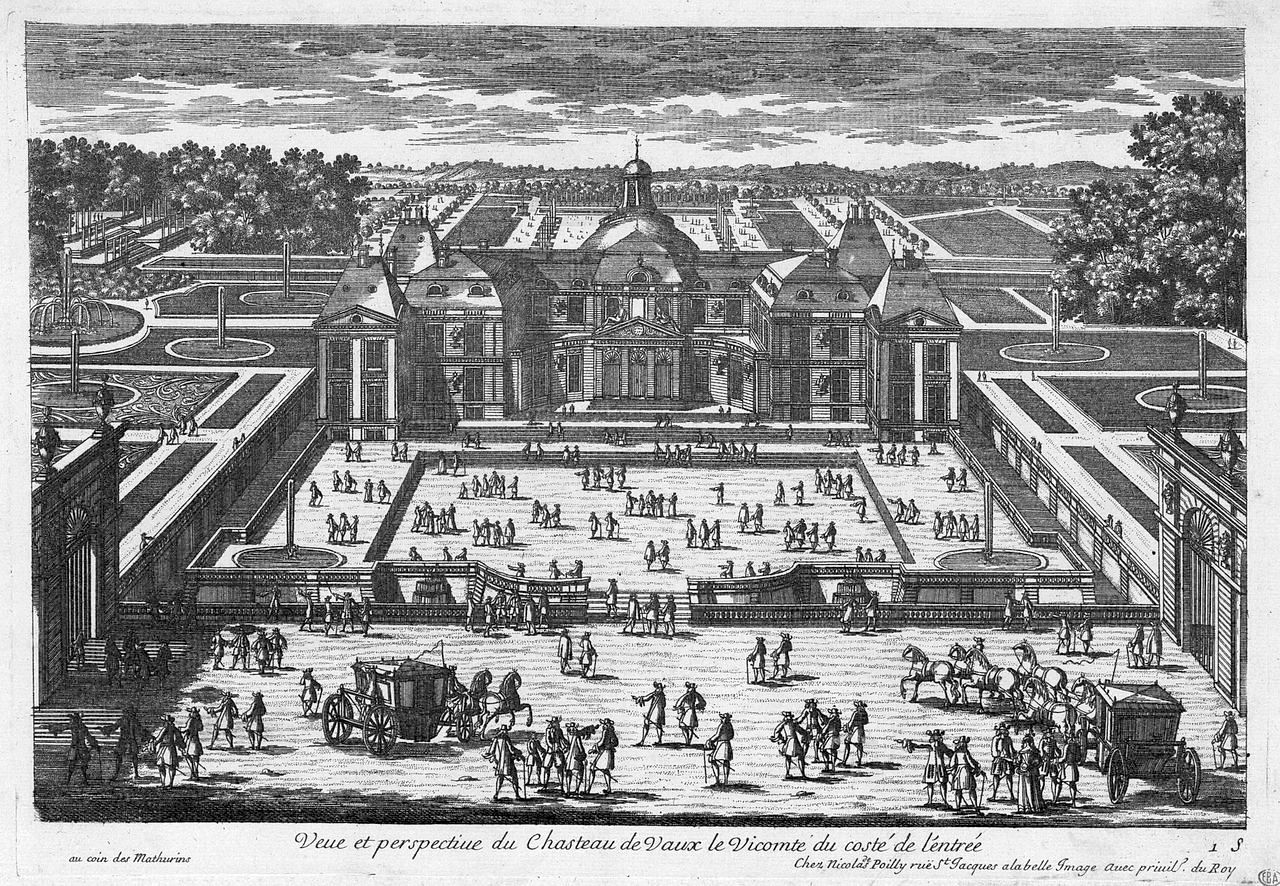

Mozarts's sound world is one of complex formal structures, carefully constructed harmonies and dissonances and beautiful tonal colour. This description could apply equally to the work of the French architect Jacques-Ange Gabriel, architect of the Place de la Concorde, Paris and the Petit Trianon, Versailles (1758-68).

Click the score to listen to Víkingur Ólafsson play Mozart's Rondo in D Major, K. 485 on YouTube.

Mozarts's sound world is one of complex formal structures, carefully constructed harmonies and dissonances and beautiful tonal colour. This description could apply equally to the work of the French architect Jacques-Ange Gabriel, architect of the Place de la Concorde, Paris and the Petit Trianon, Versailles (1758-68).

Click the score to listen to Víkingur Ólafsson play Mozart's Rondo in D Major, K. 485 on YouTube.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Score for Piano Sonata No.31 Op. 110 (1821).

>Beethoven used similar instrumentation and means of composition as Mozart, but his sound world is one of highly varied structures and emotive tonal colour. It is usually thought of as the beginning of Romanticism, but it can be regarded as music of the sublime.

Click the score to listen to Hélène Grimaud play the Piano Sonata No. 31, Op. 110 on YouTube.

>Beethoven used similar instrumentation and means of composition as Mozart, but his sound world is one of highly varied structures and emotive tonal colour. It is usually thought of as the beginning of Romanticism, but it can be regarded as music of the sublime.

Click the score to listen to Hélène Grimaud play the Piano Sonata No. 31, Op. 110 on YouTube.

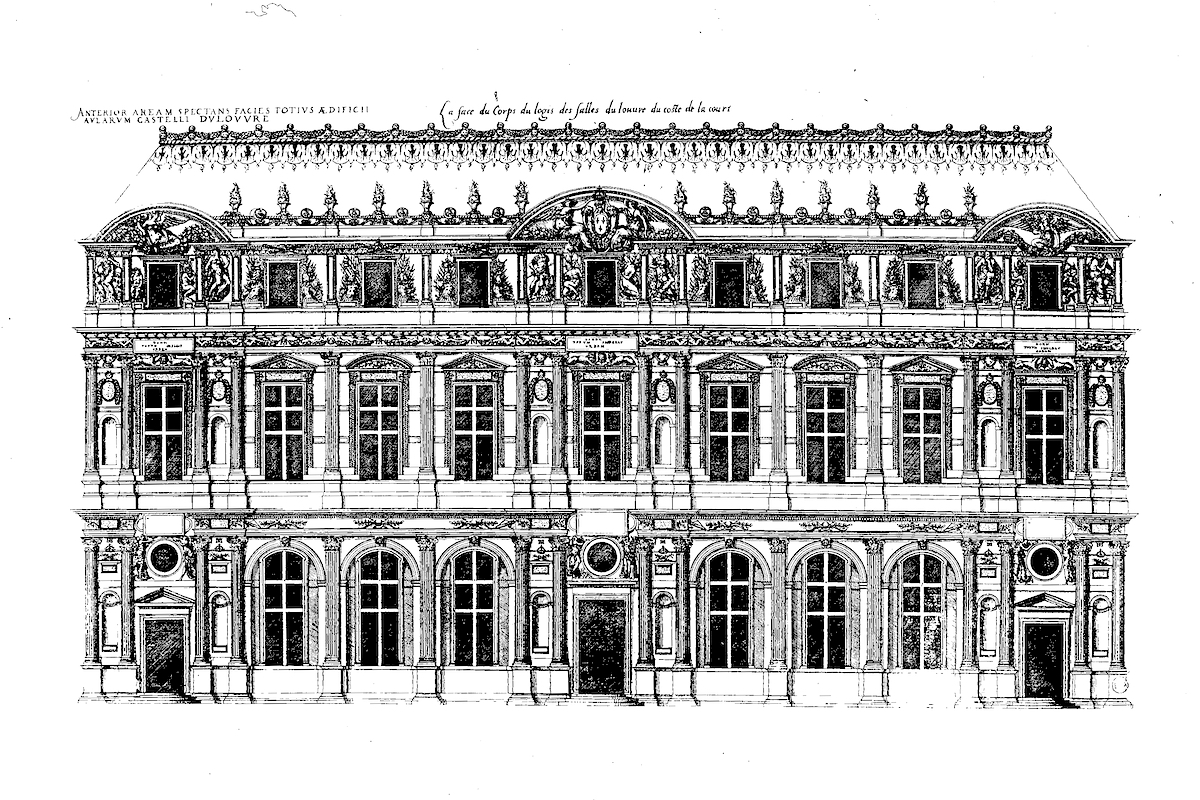

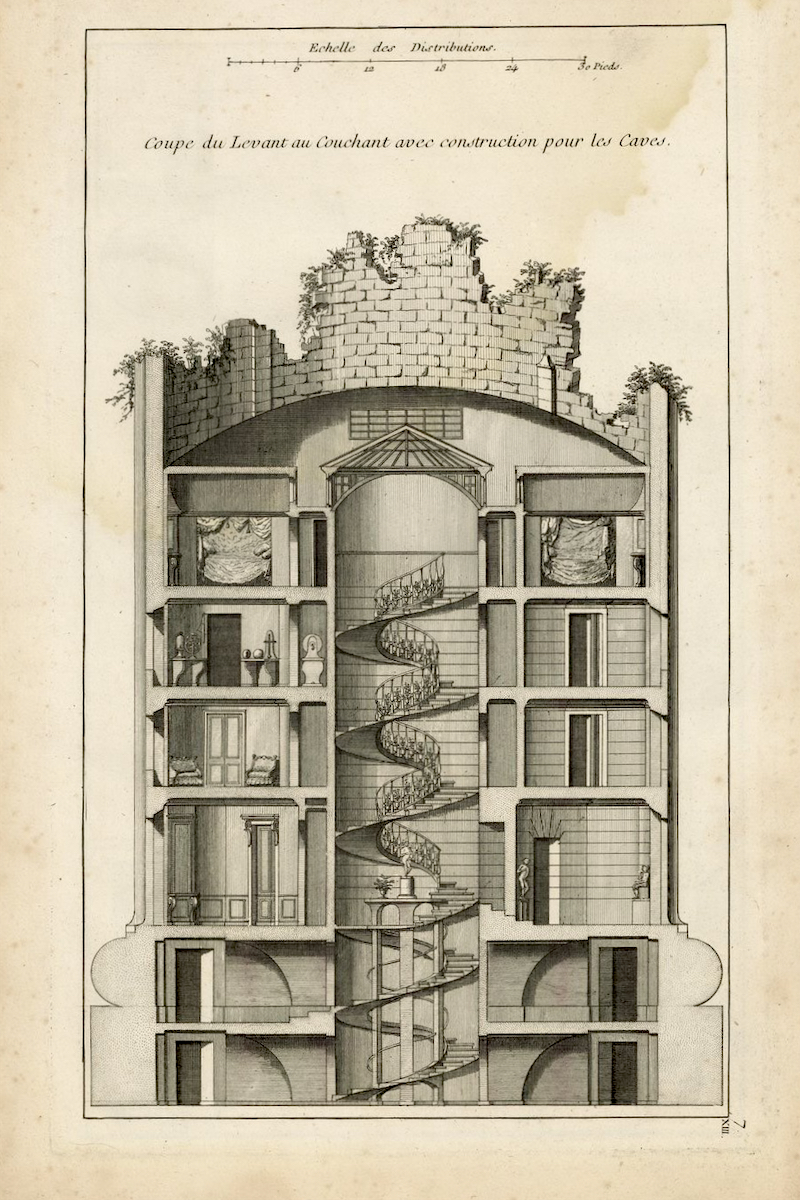

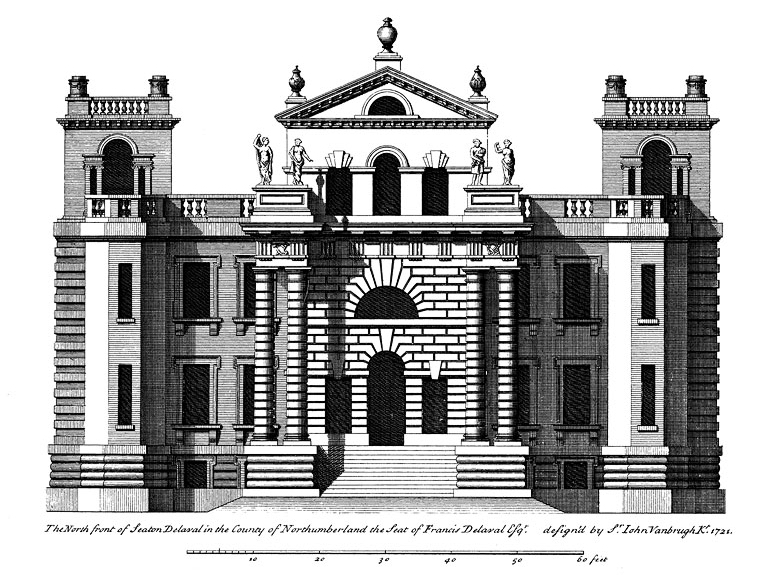

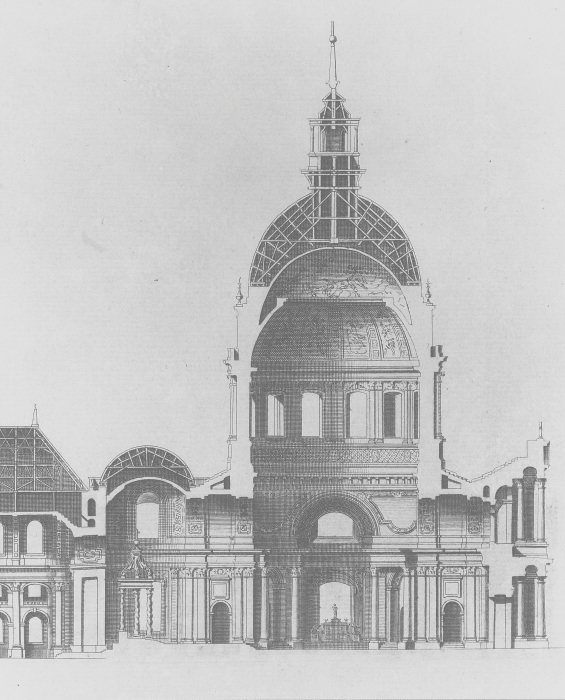

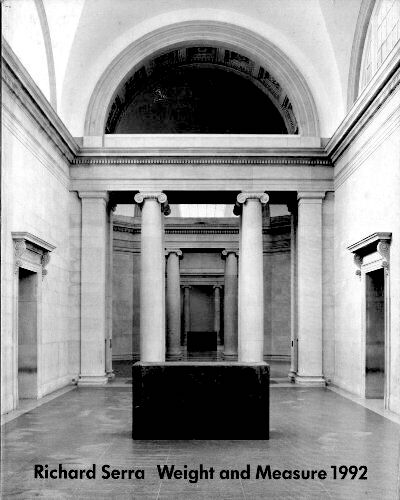

Ledoux mixed what had been highly defined and regulated orders, or designs of columns, using square columns on the ground floor, stretched proportions to give a feeling of weight and power, and massive rustication, or heavy stonework, on the base. Paired columns were acceptable, in fact, Claude Perrault had used paired columns on the East Facade of the Louvre (1667), but their use in a drum was unusual and a solid drum without a dome over an arcade was unthinkable, especially compared to the domes of the illustrious Jules Hardouin-Mansart, such as Les Invalides, Paris (1676). Ledoux's freedom in composition recalls that of Vanbrugh, admired by Ledoux but anathema to French classical architects.

Update August 2024

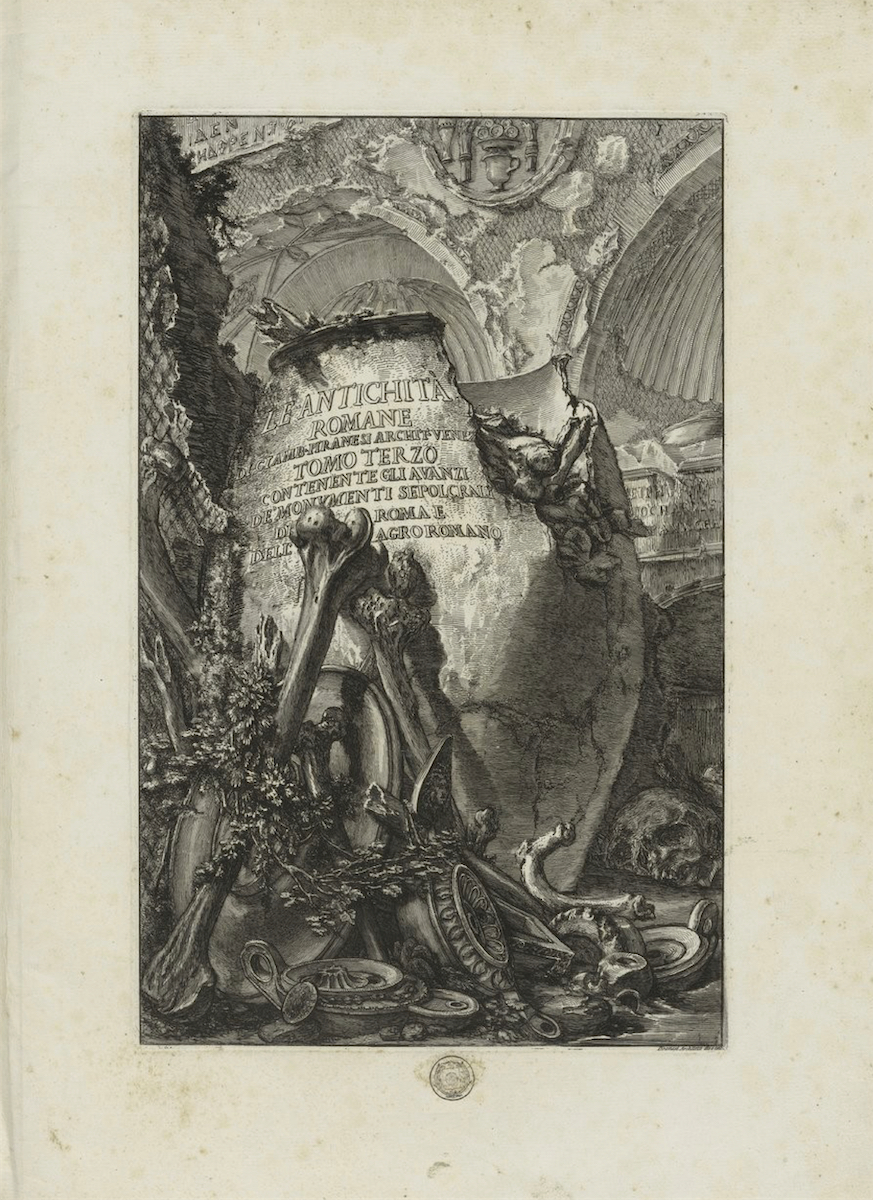

The Mausoleum of Cecilia Matella, Rome from

Giovanni Battista Piranesi: Le Antichità Romane , Volume 3 (Rome 1784)

Giovanni Battista Piranesi: Le Antichità Romane , Volume 3 (Rome 1784)

Following my visit to the Ledoux's Saline Royale, Ledoux's influences from Roman architecture have become much clearer. Ledoux apparently never visited Rome and so knew of Roman architecture only through publications. One obvious source of drawings of Roman architecture was Piranesi's Le Antichità Romane. Far from the influence of Late Antique architecture, such as the Mausoleum of Santa Constanza in Rome, as assumed by some historians, we can see Ledoux fascinated by funerary monuments such as the Mausoleum of Cecilia Matella from the 1st century BC. Ledoux' projects for the Canon Foundry and a woodcutter's house show him experimenting with forms like the so-called Pyramid of Cestius, another contemporary Roman mausoleum (shown in the illustration below). Santa Constanza, while bearing some resemblance to the Barrière St Martin, was converted into a church and Piranesi's illustration shows it as such, and in a very dilapidated state. On the other hand, the Imperial Roman mausolea were themselves removed from the conventions of Roman public building, and the sublime was an obvious and appropriate response. Louis Kahn, of course, followed Ledoux in his love of Imperial Roman architecture.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi: Le Antichità Romane (Rome 1756/7)

The 4 volumes of Piranesi's The Antiquities of Rome followed his Imaginary Prisons. We can see how Imperial Roman buildings, roughly 100BC-200AD, appealed to Ledoux. The Mausoleum of Cecilia Matella (above) and the Pyramid of Cestius (rollover, left) have the formal power found in Ledoux's work.

The 4 volumes of Piranesi's The Antiquities of Rome followed his Imaginary Prisons. We can see how Imperial Roman buildings, roughly 100BC-200AD, appealed to Ledoux. The Mausoleum of Cecilia Matella (above) and the Pyramid of Cestius (rollover, left) have the formal power found in Ledoux's work.

Claude-Nicolas Ledoux: Barrière St Martin, Paris (1785-1790)

© Thomas Deckker 1984

© Thomas Deckker 1984

It is one of the ironies of history that the Barrière de la Villette, having beeen restored and beautified, became a not-particularly-up-market bistro. The drum, originally left as a void in a calculated reversal of classical ideals, has been roofed in, joining the many urban spaces now enclosed with iron (or steel) and glass. On the other hand, the square in front the Barrière, a car park when I visited, is now a fully functioning public space.

The afterlife of the Barrière de la Villette and scenes of 'modern life'

The barrières were intended to control and tax the entry of food and wine into Paris. They led to an upsurge in the popularity of guingettes, or informal dance halls, immediately outside the wall. Guingettes remained popular throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, often painted as scenes of 'modern life' by the Impressionists.

Claude Monet: Bathers at La Grenouillère (1869)

National Gallery, London NG4119

National Gallery, London NG4119

Thomas Deckker

London 2022

London 2022