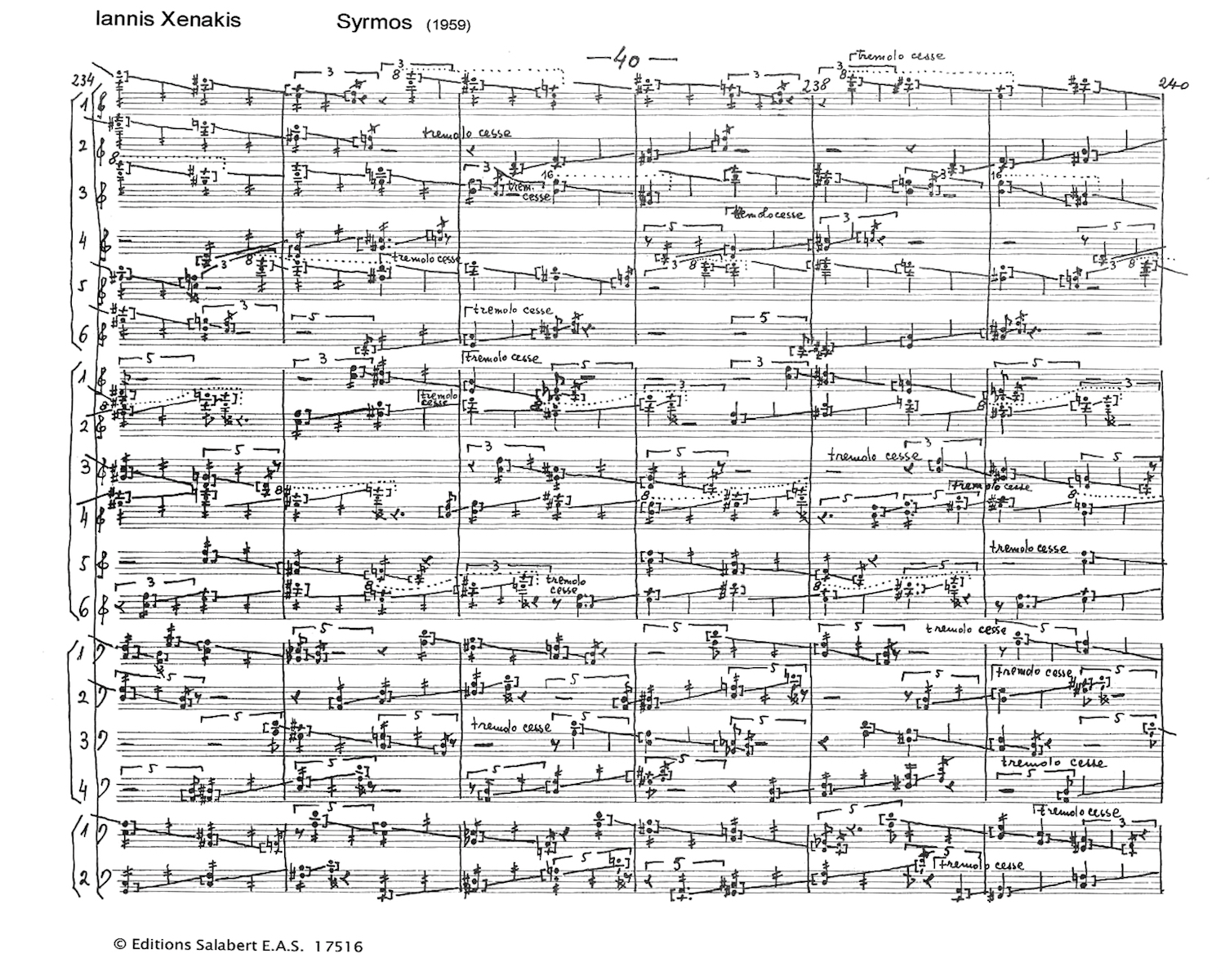

Out of the self-indulgent and self-obsessed chaos of ‘serious’ music in the 1950s and 1960s the composer, engineer and architect Iannis Xenakis stands out as a rational and approachable composer. Xenakis was the founder and principal exponent of stochastic music: combinations of musical patterns that are generated by mathematical processes but whose outcomes cannot be predicted. Xenakis applied these theories in both music and architecture: strangely war was, in many ways, an epiphany in his intellectual development.

Xenakis was born in Romania of a Greek family, and studied engineering in Athens before WWII. During the war Xenakis was in the Greek resistance, and then and during the ensuing civil war encountered war at first hand. After fleeing Greece because of his communist sympathies, Xenakis settled in Paris and began work with Le Corbusier, initially as an engineer. He did not have, at this time, any idea of pursing a career in music or architecture.

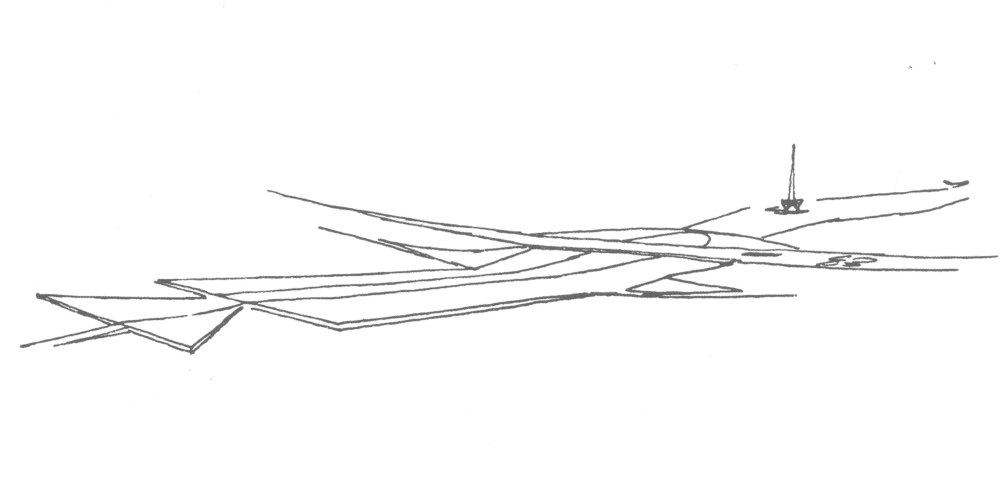

Xenakis developed his theories of stochastic composition in Le Corbusier's studio. He recalled the chanting of crowds in demonstrations that he had witnessed in Athens and volleys of gunfire as examples of found stochastic sounds. Somewhere I heard him tell a story that, during one battle, he escaped from the German guns though a pass in the mountains, but paused and turned back in the pass, at great risk to his life, captivated by the patterns of tracer fire in the valley below. The story that it was here that he lost his eye is apocryphal, however. I like to think of this experience as his first epiphany.

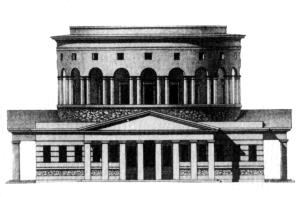

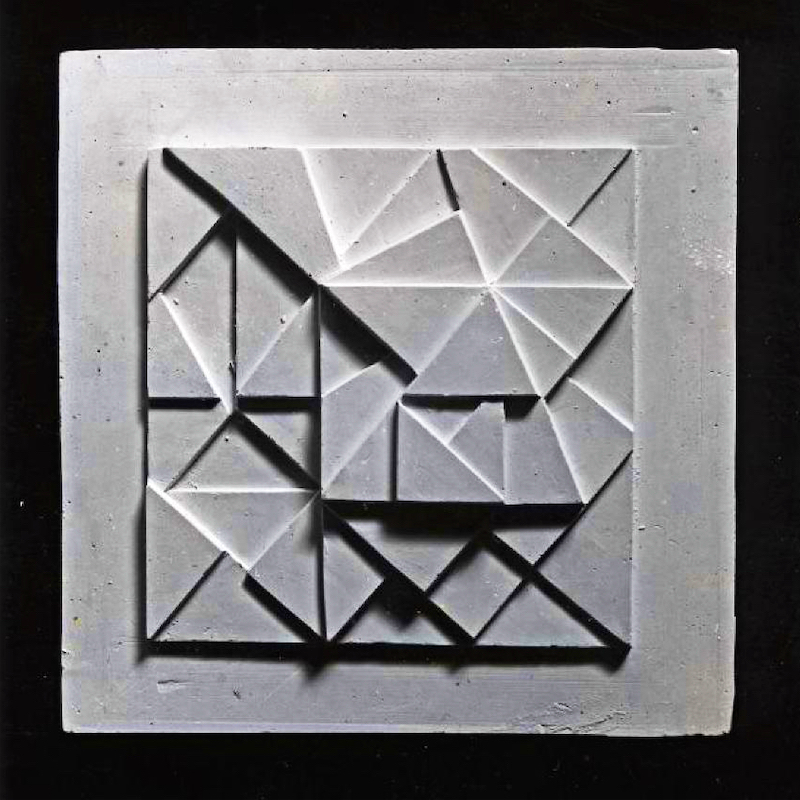

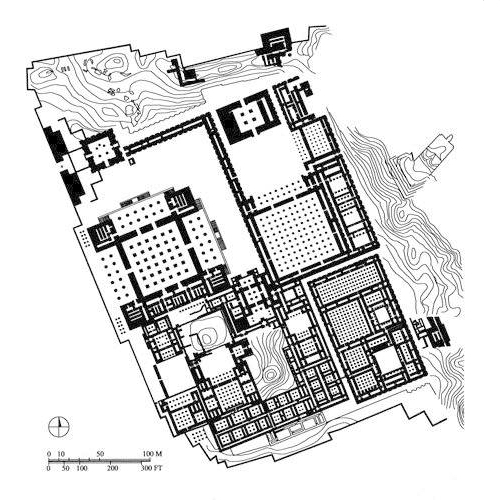

Xenakis's meeting with Le Corbusier was a second epiphany; it made him realise his own desire for and capabilities in design and composition. His first role was as engineer, and then architect, for the Couvent de la Tourette, the Benedictine teaching monastery designed and built between 1953-60. He introduced what Le Corbusier called ondulatoires, a mullion wall based on stochastic patterns - a varying sequence of larger and smaller window panes - the major mullions in concrete, the minor transoms in steel - that defined the public spaces, in contrast to the fixed sizes of windows in the individual monks cells.

thomas

deckker

architect