thomas

deckker

architect

critical reflections

Henri Labrouste and the construction of mills

2023

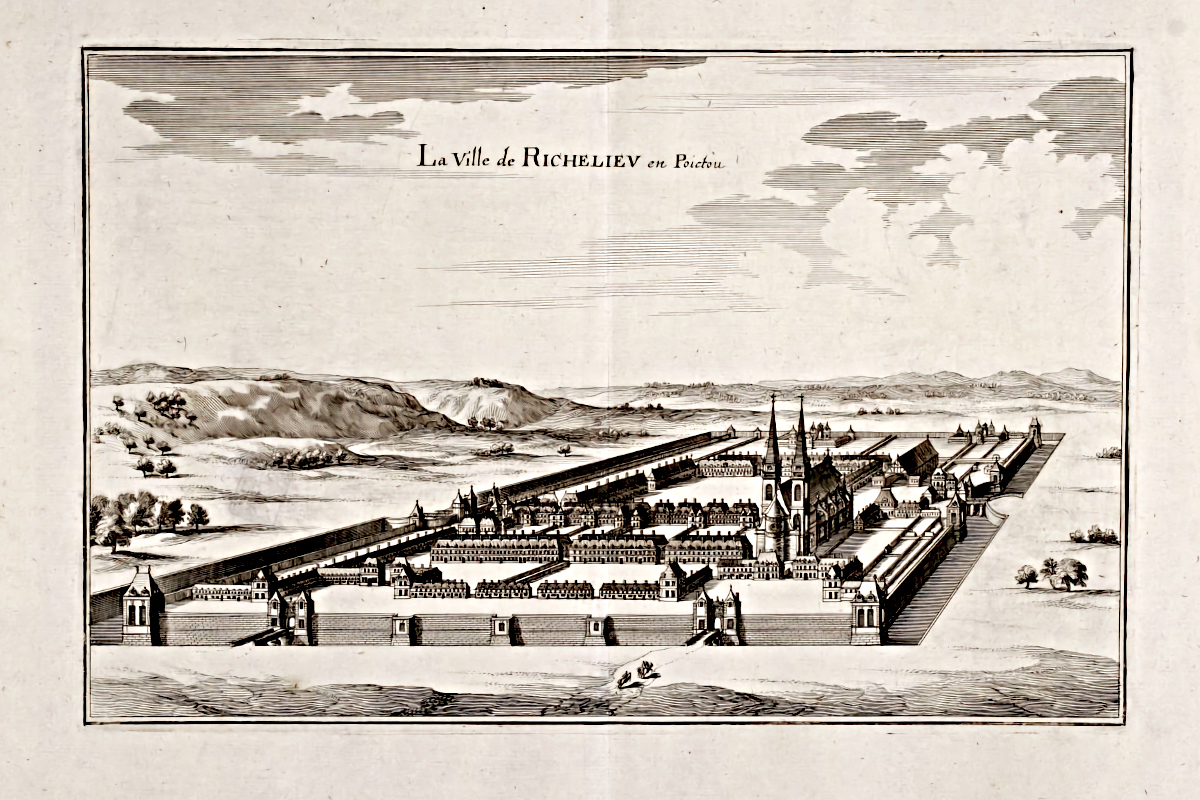

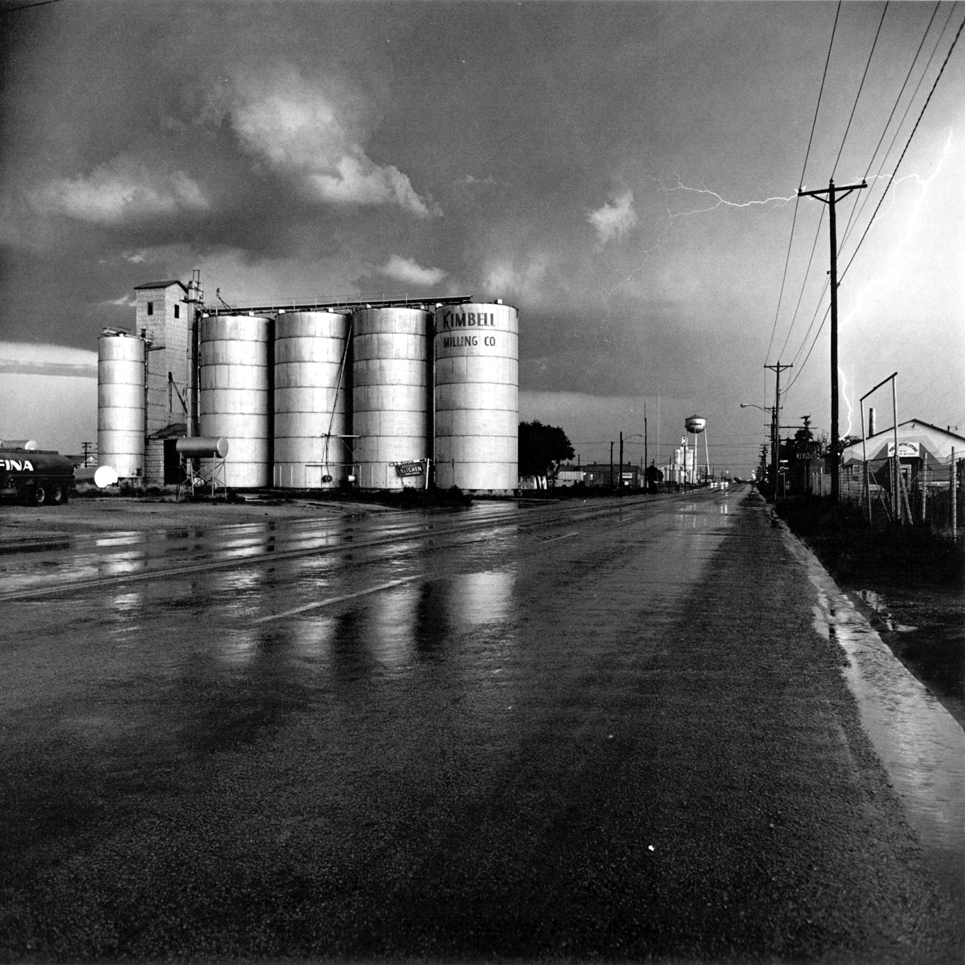

Derelict Building, Kings Cross

photo © Thomas Deckker 1988

photo © Thomas Deckker 1988

Henri Labrouste and the construction of mills

Architects of the Modern Movement knew the work of Henri Labrouste, if they knew of it at all, through Sigfried Giedion's publication of photographs of the book stacks at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Space, Time and Architecture, published by Harvard University Press in 1941. Sigfried Giedion, like Nikolaus Pevsner in Pioneers of the Modern Movement: from William Morris to Walter Gropius, published by Faber in 1936, sought to place Modernism at the end of a trajectory of which the work of nineteenth century architects was an inchoate precursor.

Henri Labrouste: Book stacks at the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris (1860-68)

© Bibliothèque National de France

© Bibliothèque National de France

Labrouste's reputation was rehabilitated, fortunately, by Arthur Drexler, Director of the Department of Architecture and Design at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in The Architecture of the Ècole des Beaux-Arts, in 1975, and then by Corinne Bélier, Barry Bergdoll & Marc Le Coeur in the magnificent Henri Labrouste: Structure Brought to Light also by The Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 2013. It was perhaps surprising that the Museum of Modern Art, New York, should have been interested in nineteenth century architecture, having been single-handedly responsible for promoting the Modern Movement in the United States, starting with Modern architecture: international exhibition in 1932. In 1936, however, the Museum had published The Architecture of H. H. Richardson and his Times. Richardson, undeniably one of the great nineteenth century architects, had a close connection to Labrouste: he had studied architecture at the École des Beaux-Arts and worked for Theodore Labrouste, Henri Labrouste's brother, in Paris.

Henri Labrouste: Survey and Conjectural Reconstruction of the Temple of Hera, Paestum (1830)

© Bibliothèque National de France

© Bibliothèque National de France

roll over drawing above for Labrouste's conjectural reconstruction

The Temple of Hera has, unusually for a Greek temple, a row of columns in the naos or central room. Their fascination with Greek architecture led Labrouste's generation to be labelled neo-grec.

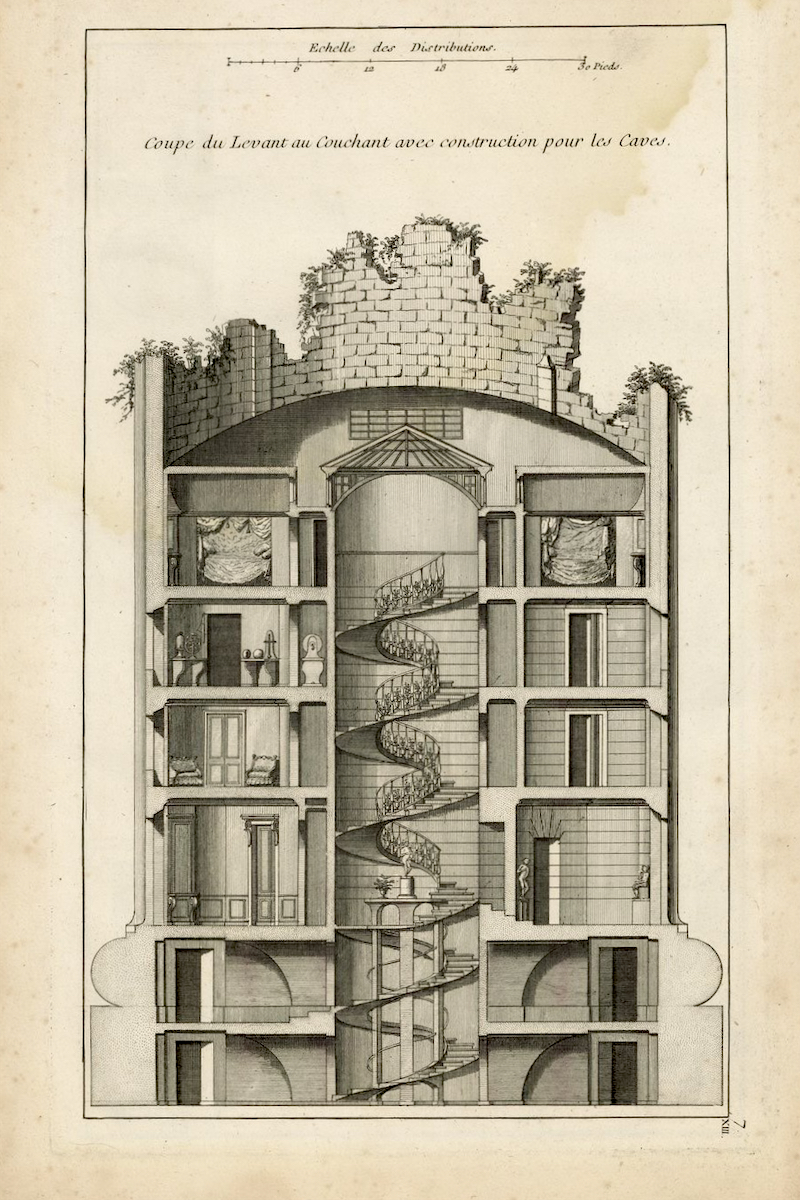

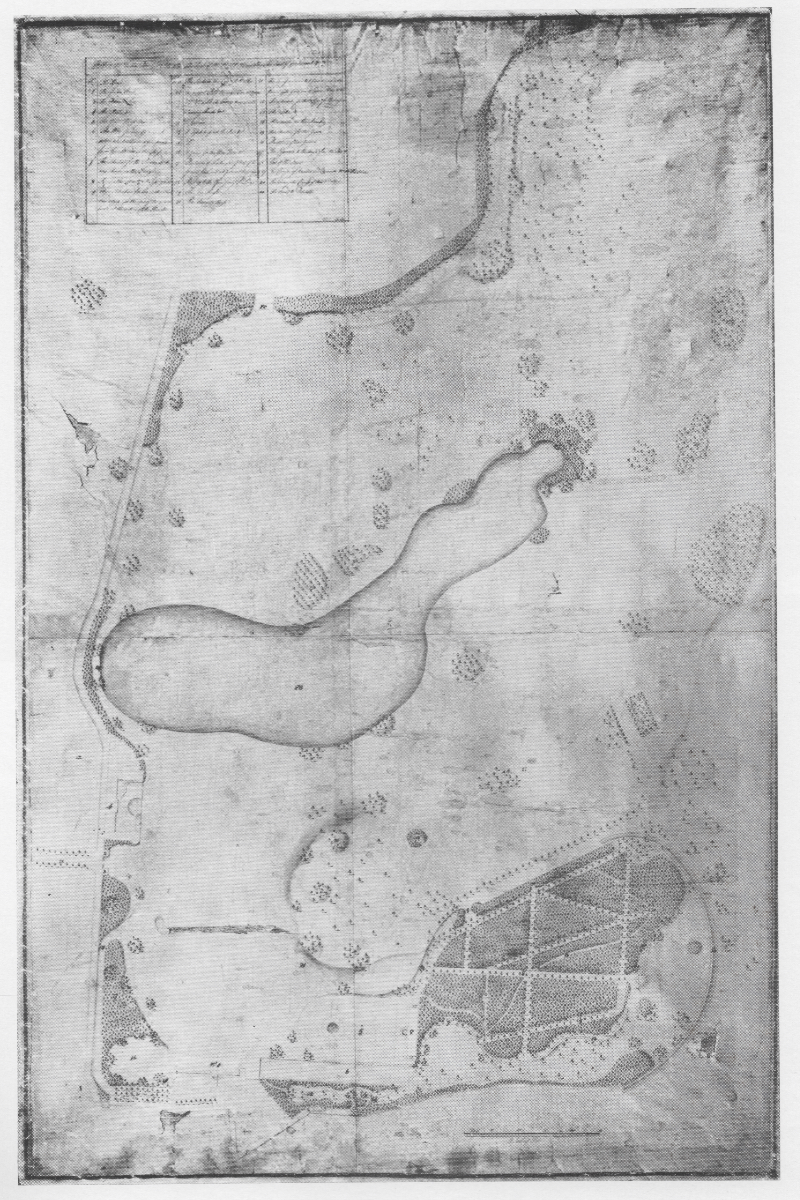

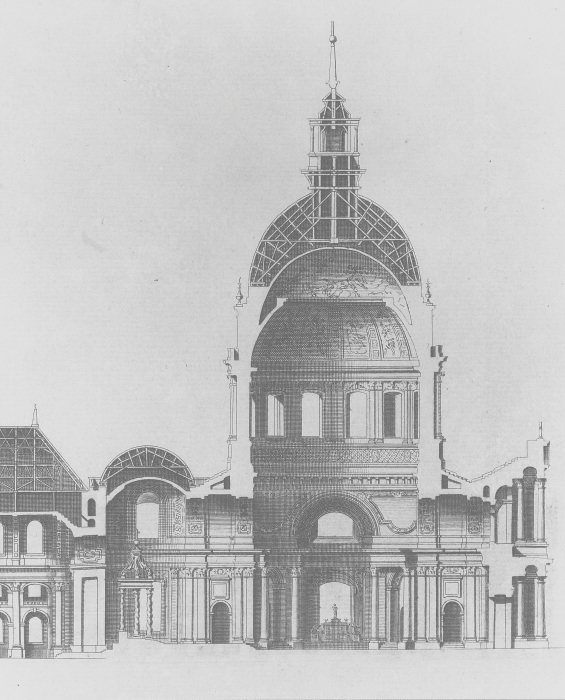

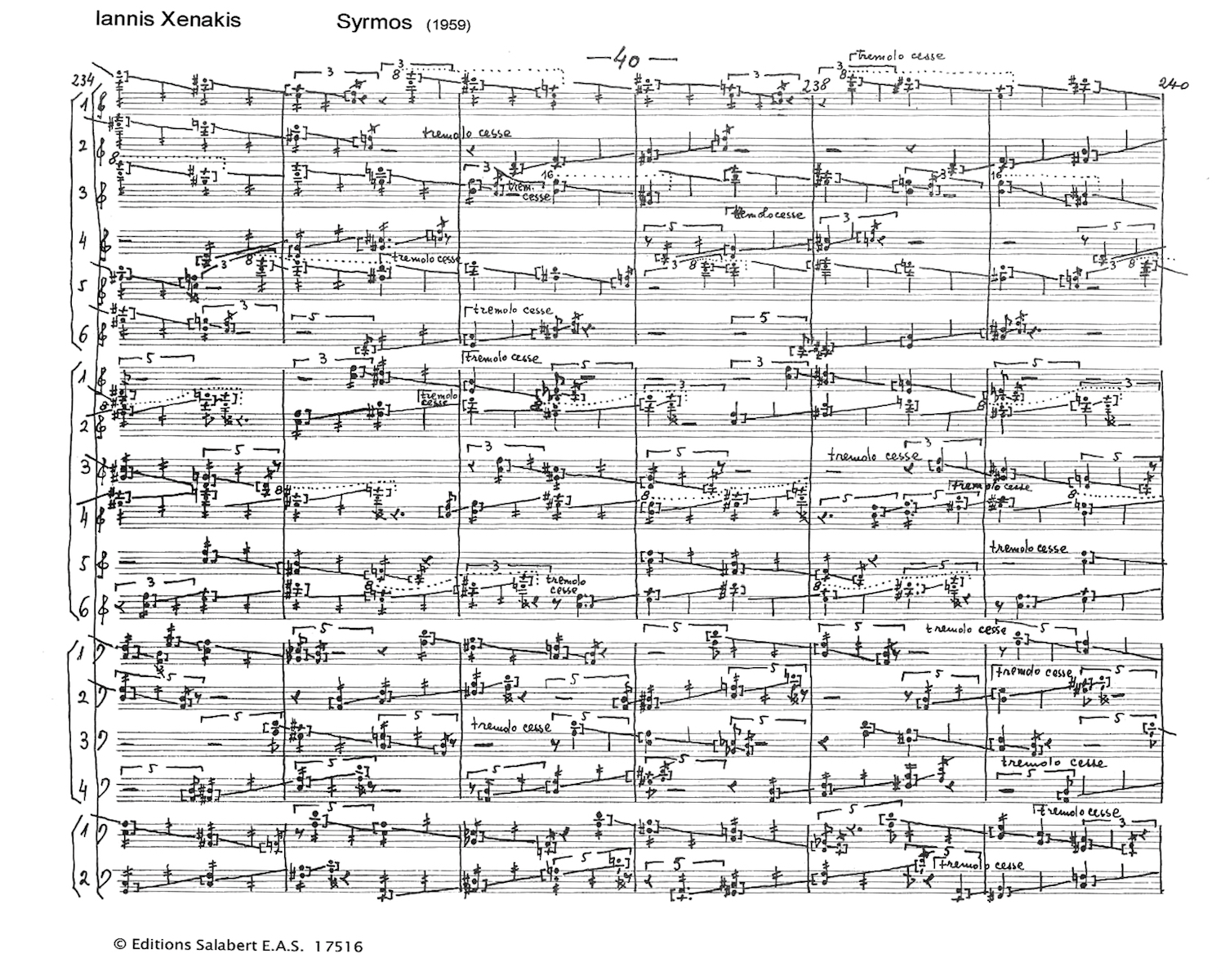

Labrouste's many sources of inspiration have been extensively documented, such as his conjectural reconstruction of the Temple of Hera, Paestum, after winning the Prix de Rome at the Ècole des Beaux-Arts. Less well known is the extent to which mill construction had come to exemplify modern construction, and a modern sensibility of space. Prior to mill construction, with a grid of thin internal columns, internal space in architecture was defined by rooms or by construction similar to external walls. Labrouste not only employed mill construction but his working drawings for the Bibliothèque Ste Geneviève, Paris 1838-50 celebrate the new technical possibilities of cast iron, wrought iron and masonry jack arches.

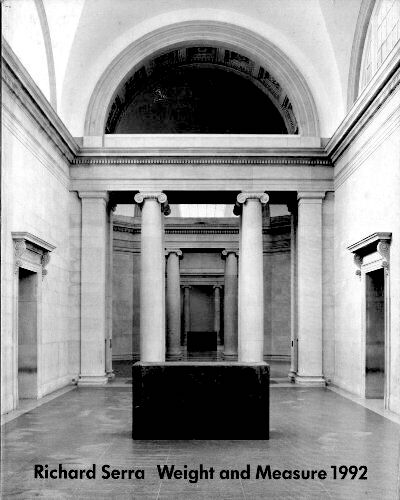

Henri Labrouste: design drawing for the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève

© Bibliothèque Nationale de France

© Bibliothèque Nationale de France

Henri Labrouste: design drawing for the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève

© Bibliothèque Nationale de France

© Bibliothèque Nationale de France

Labrouste clearly shows the 3 main components of the construction of the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève: the wrought iron roof trusses, in red, the cast iron dendriform columns, in grey, and the masony walls, in pink. Wrought iron could take tensile loads, cast iron compressive loads, and the thick masonry walls provided a structural and environmental enclosure.

I visited the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève before the great clean-up in Paris, when the Place du Panthéon, which it faces, was still a giant car park and the building itself was quite dingy [1]. It is strange how architects of the Modern Movement, even considerably watered down ideologically by the 1980s, despised 19th century architecture. The building is now rightly regarded as dense with serious and logical ideas, and not evidence of chaos and confusion. The neo-grec was catalogued by Neil Levine in "The Book and the Building" in Robin Middleton (ed): Beaux-Arts and Nineteenth-Century Architecture (MIT 1982) and in "The Romantic Idea of Architectural Legibility" in The architecture of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. The neo-grec was the first of the 3 clear phases of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts: followed by an Imperial Roman phase, exemplified by Charles Garnier's Opéra (1861-75) and then by an art nouveau phase, exemplified by Victor Laloux's Gare d'Orsay, Paris (1898-1900).

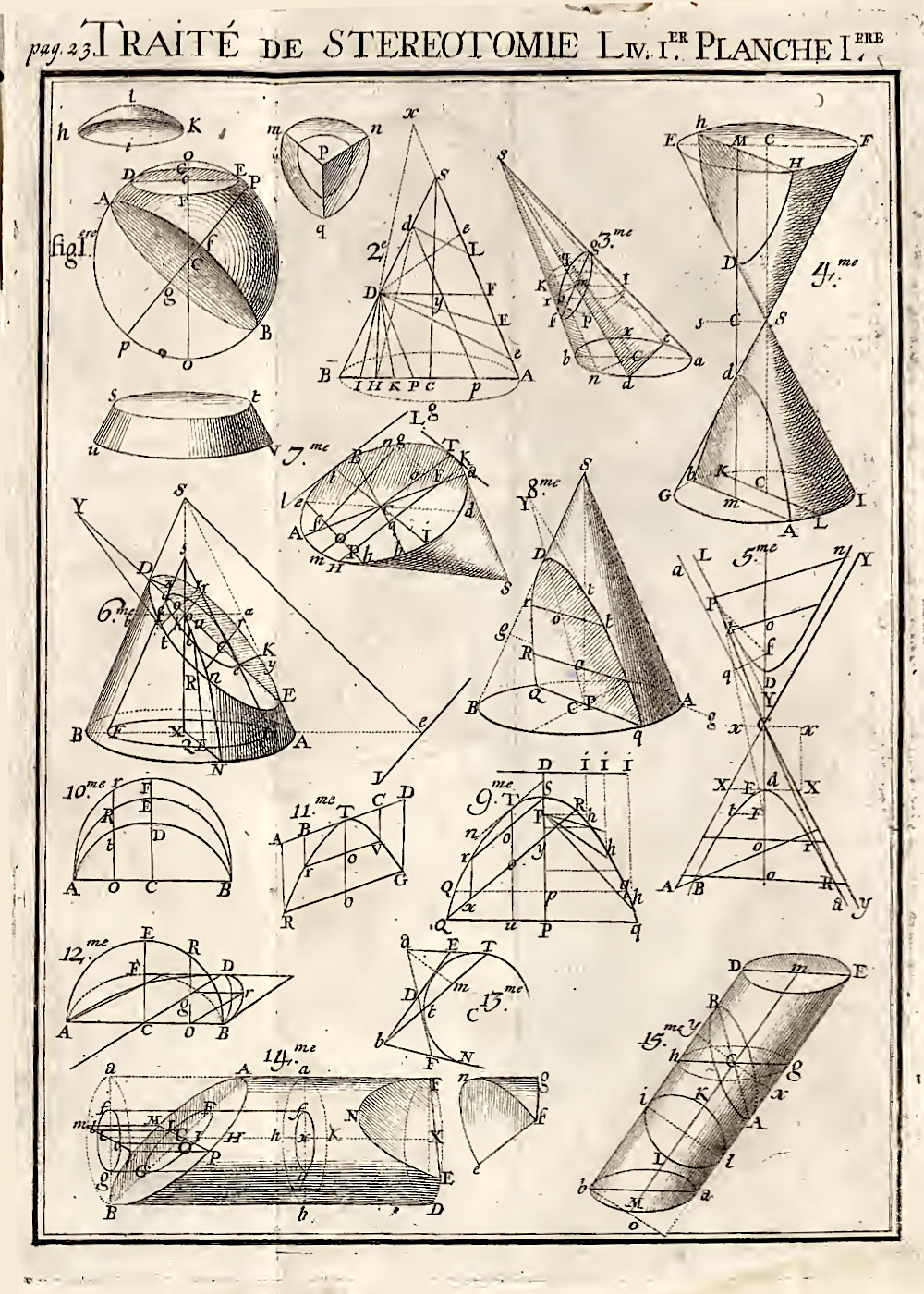

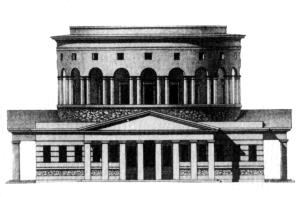

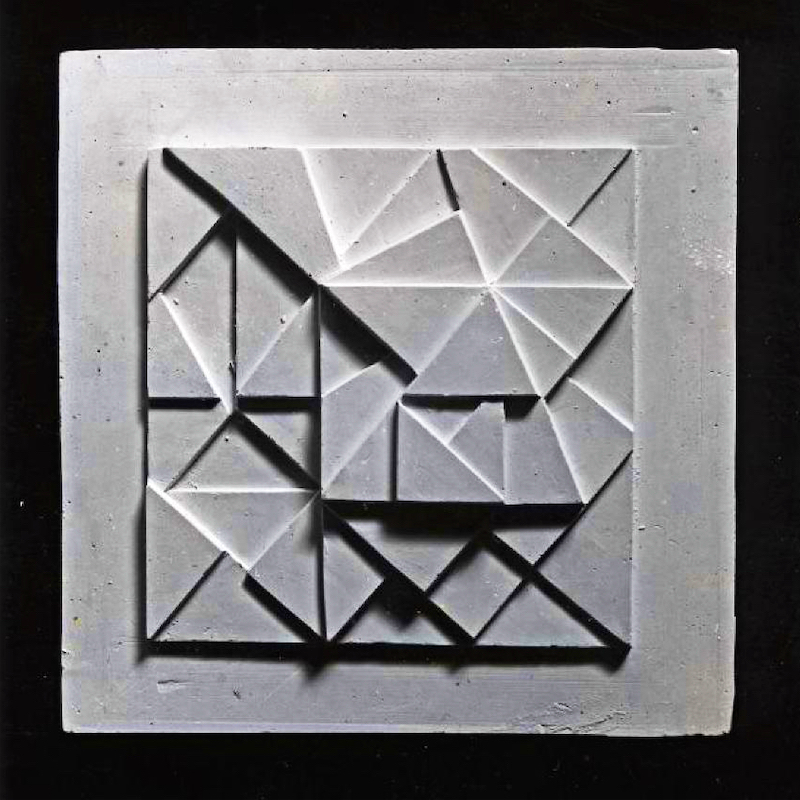

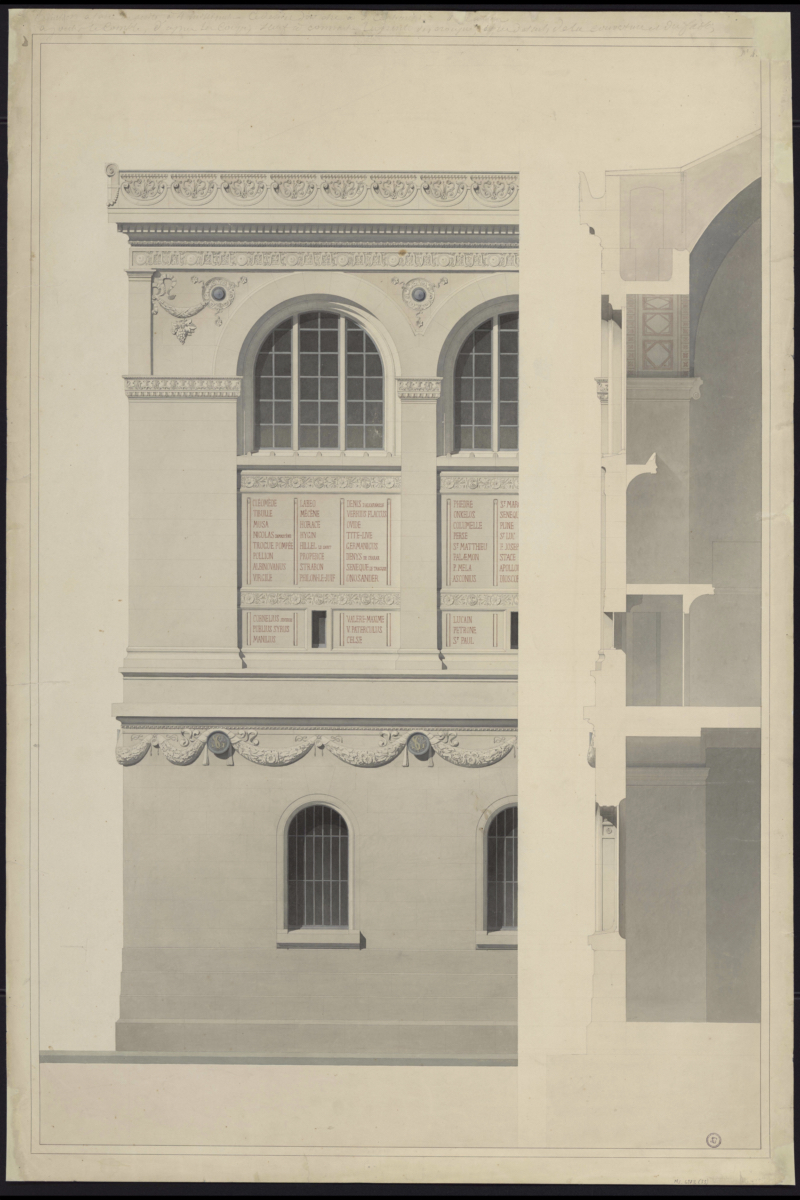

Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand: Deuxième Partie. De la Composition en Général.

from Nouveau Précis des Leçons d'Architecture (Paris 1813)

from Nouveau Précis des Leçons d'Architecture (Paris 1813)

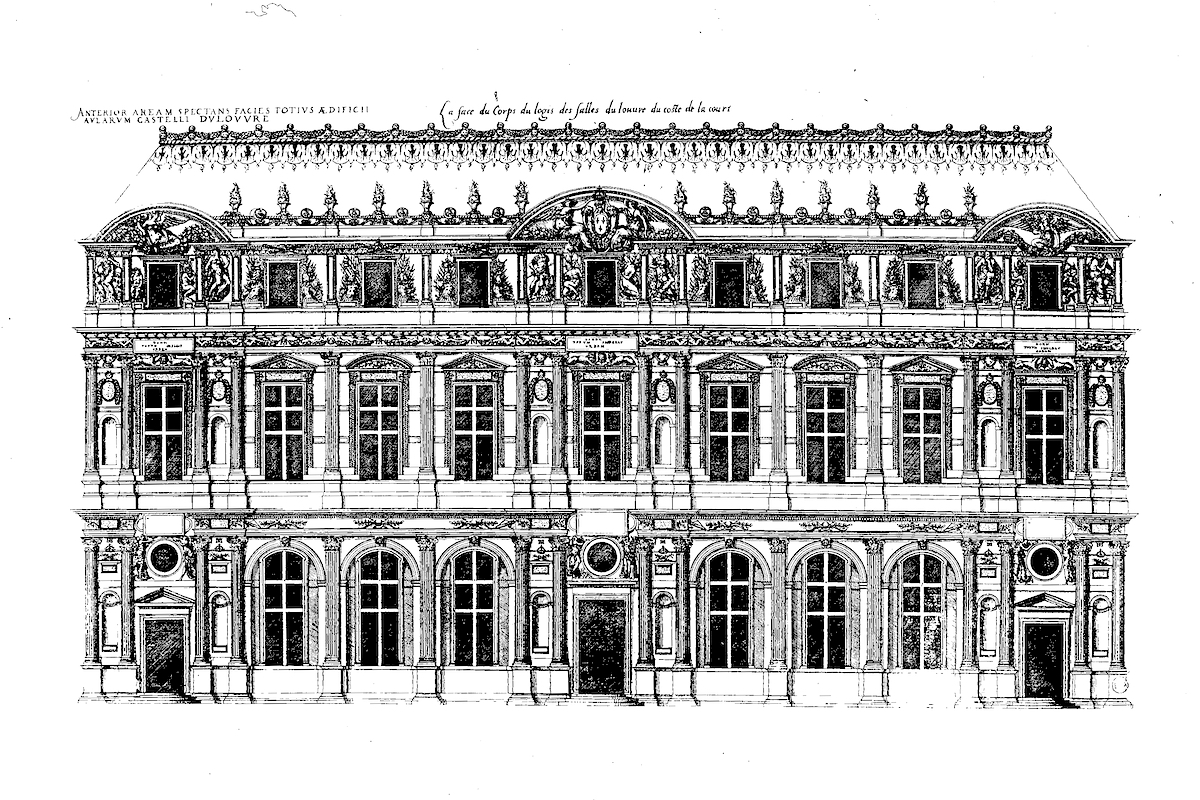

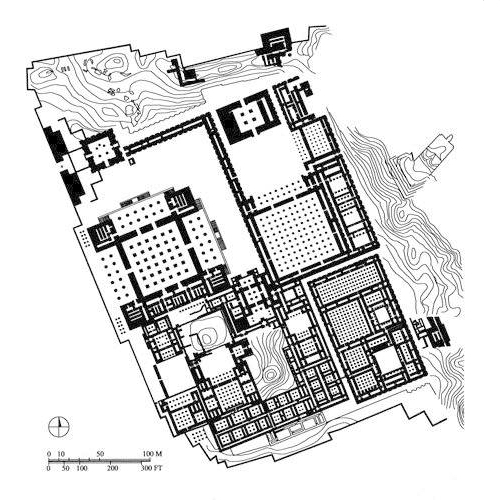

The spatial aspects of mill construction had been abstracted and formed into a general theory of architecture by the French architect Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand, who taught architecture at the École Polytechnique in Paris, the school of construction and engineering distinct from the École des Beaux-Arts which taught art and design. Durand was nevertheless incredibly influential: he was the first architect to draw buildings with grids, which he published in Précis des leçons d'architecture in 1802-05. To extend his theory he published many of the major buildings of the known world redesigned on square grids - which led to some strange distortions - in Recueil et parallèle des édifices de tout genre , in 1800. Durand's grids were a logical extension of French neo-classical theory, but the pratical underpinnings lay in mill construction. Durand's theories explicitly separated logical planning from appearance.

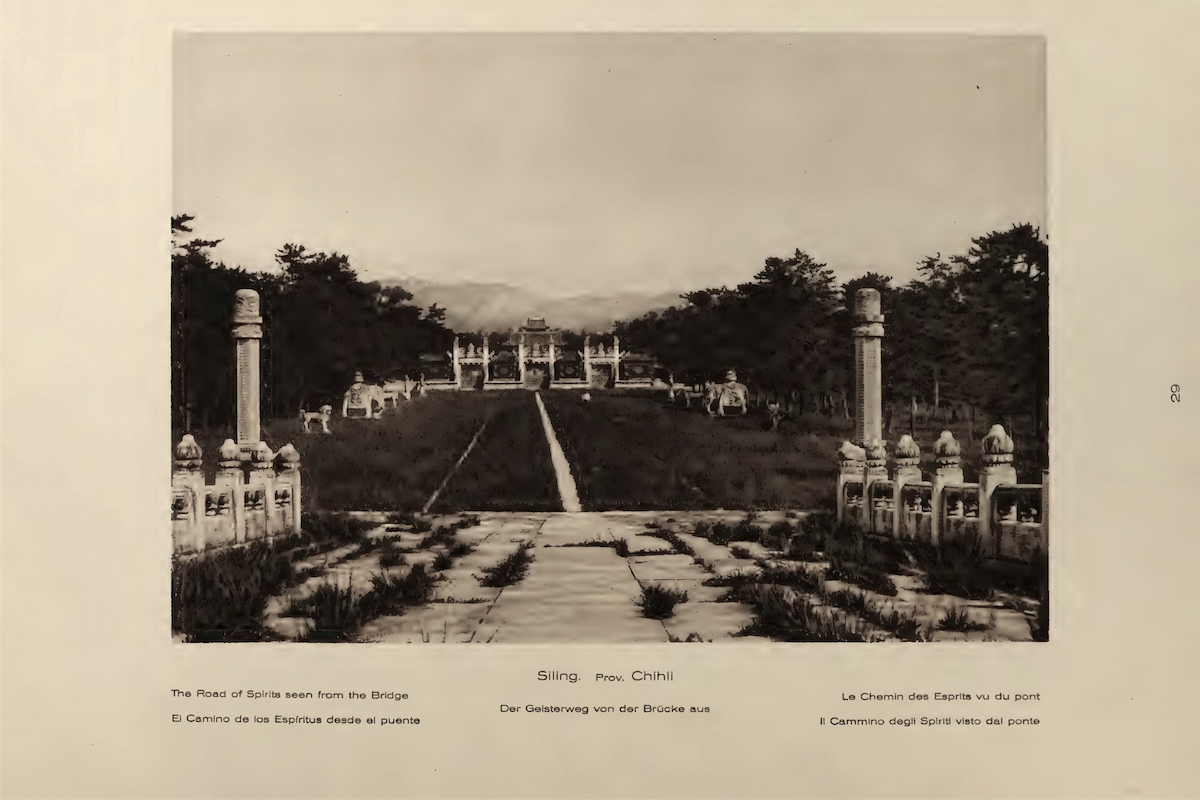

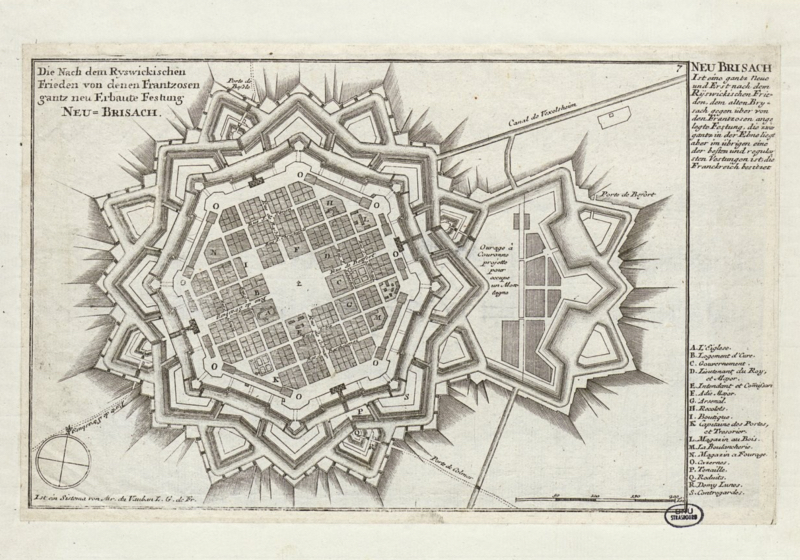

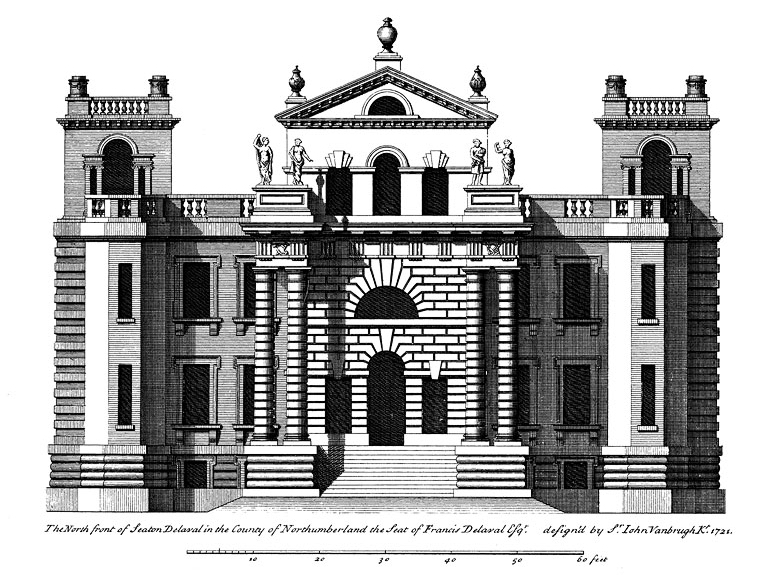

Karl Friedrich Schinkel was a great pioneer of mill construction in Prussia, as much as Labrouste in France. Schinkel's Bauakademie in Berlin (1838-50) was sadly demolished in 1962 after - just - surviving the Second World War. Schinkel had been brought up equally on the academic rigour of the French architect Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand and on revolutionary industrial mill architecture in England.

Karl Friedrich Schinkel: photograph of the Bauakademie, Berlin (1838-50), prior to demolition

© Zentralarchiv, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

© Zentralarchiv, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

The mill construction is plainly visible: wrought iron beams and ties, holding masonry jack arches. The column is stone, not cast iron. Schinkel had looked at mill buildings in England and Scotland as a spy for the Prussian state in 1826. Schinkel consciously modelled the Bauakademie on the mill buildings he had seen in England. Note the central columns and the rigorous grid derived from Durand

Karl Friedrich Schinkel: first floor plan, Bauakademie, Berlin (1838-50)

© Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

© Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

It is extraordinary to think that Durand published his Précis des leçons d'architecture just a few years after Claude-Nicolas Ledoux designed and built his Barrière St Martin in Paris, and even more so that the first mills were being built in England at almost the same time as the barrières in Paris. Ledoux's governing concept was still form. The photograph at the top is of the Coal Yards, Kings Cross, built in the 1850s and thus almost contemporary with the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève. Despite the central columns there is no known connection to either Labrouste or Schinkel.

Footnotes

1. The overiding reason for the great clean-up must be globalisation and deindustrialisation, which removed manual industries and their requirement for manual labour from many cities including Paris.

In Paris it may be attributable to two simultaneous events in 1977, although the effects took many years to be manifest. The first was the creation of the role of Mayor of Paris, the first incumbent being the ex-Prime Minister, and later President, Jacques Chirac. The second was the opening of the Centre Pompidou in the Marais, which led to the positive reevaluation of historic architecture in Paris, including the installation of the Musée national Picasso-Paris in the 17th-century Hôtel Salé in 1985.

A consequence of the great clean-up may be seen in the 1992/93 Maigret series with Michael Gambon, which was shot in and around Budapest, while the 1959/63 Maigret series with Rupert Davis was still shot in Paris.↩

In Paris it may be attributable to two simultaneous events in 1977, although the effects took many years to be manifest. The first was the creation of the role of Mayor of Paris, the first incumbent being the ex-Prime Minister, and later President, Jacques Chirac. The second was the opening of the Centre Pompidou in the Marais, which led to the positive reevaluation of historic architecture in Paris, including the installation of the Musée national Picasso-Paris in the 17th-century Hôtel Salé in 1985.

A consequence of the great clean-up may be seen in the 1992/93 Maigret series with Michael Gambon, which was shot in and around Budapest, while the 1959/63 Maigret series with Rupert Davis was still shot in Paris.↩

Thomas Deckker

London 2023

London 2023