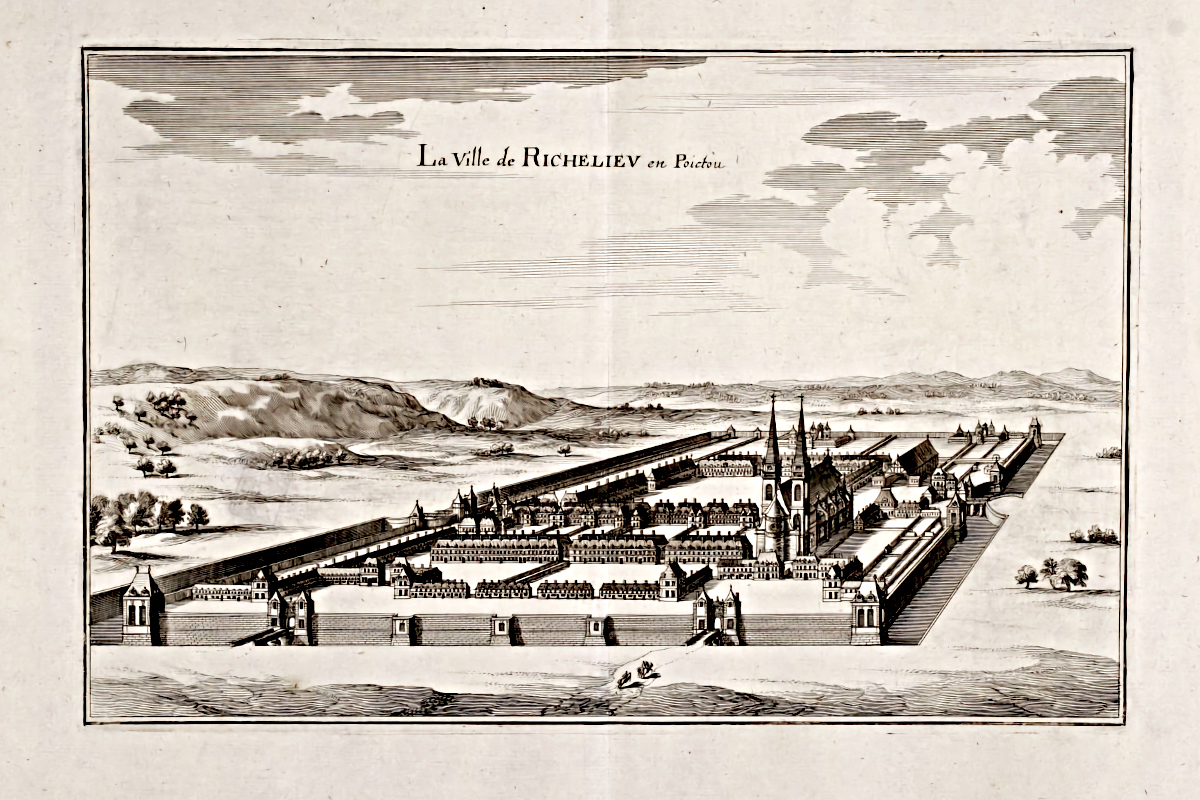

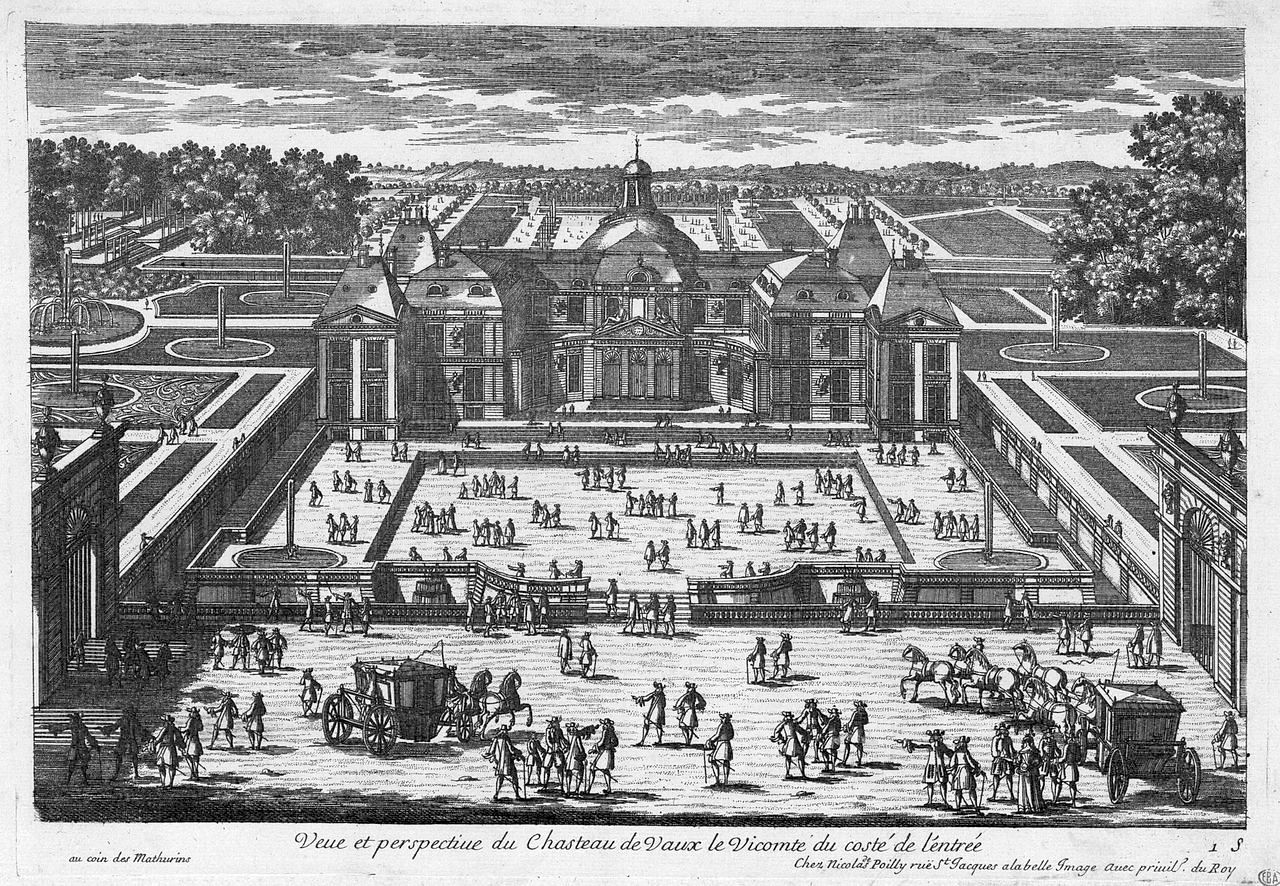

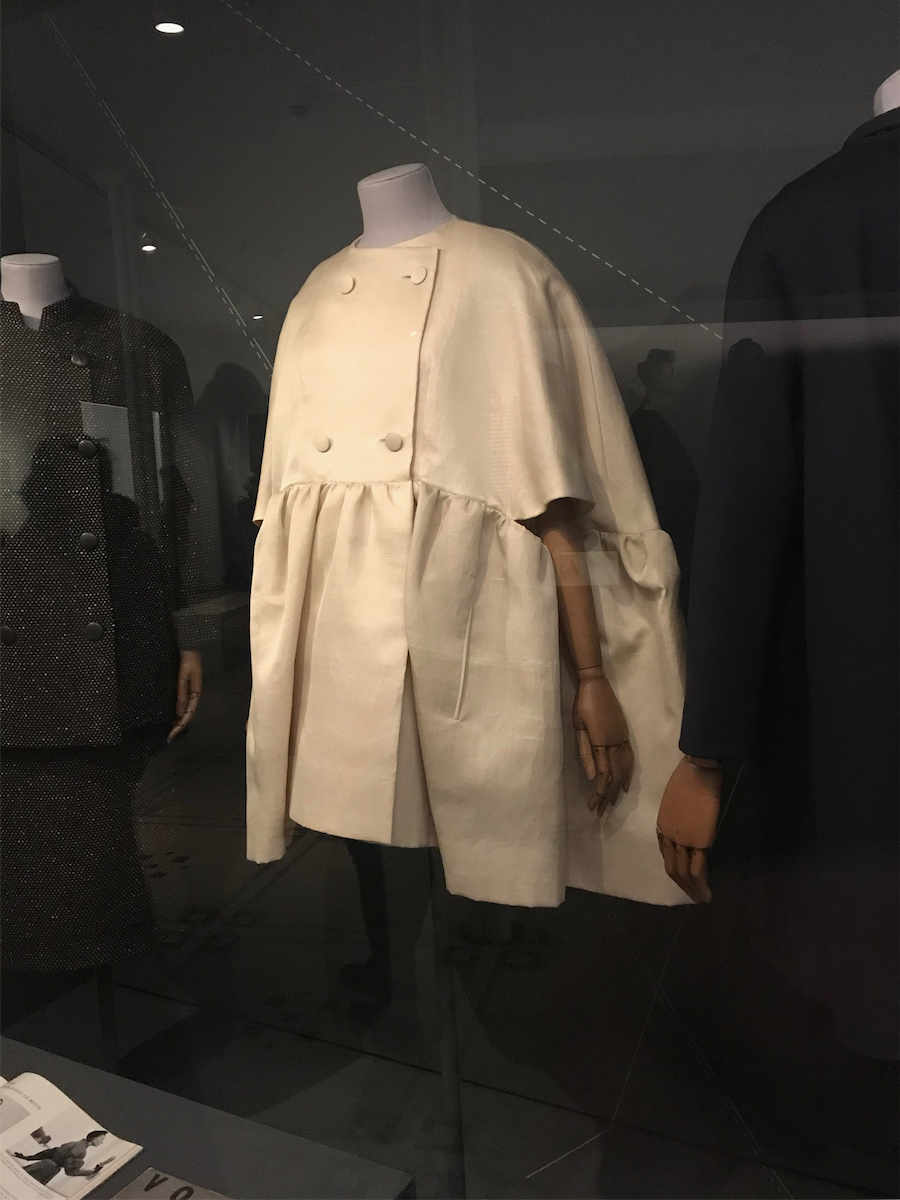

Cristobal Balenciaga: Skirt Suit, 1964

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The rise and fall of Cristobal Balenciaga

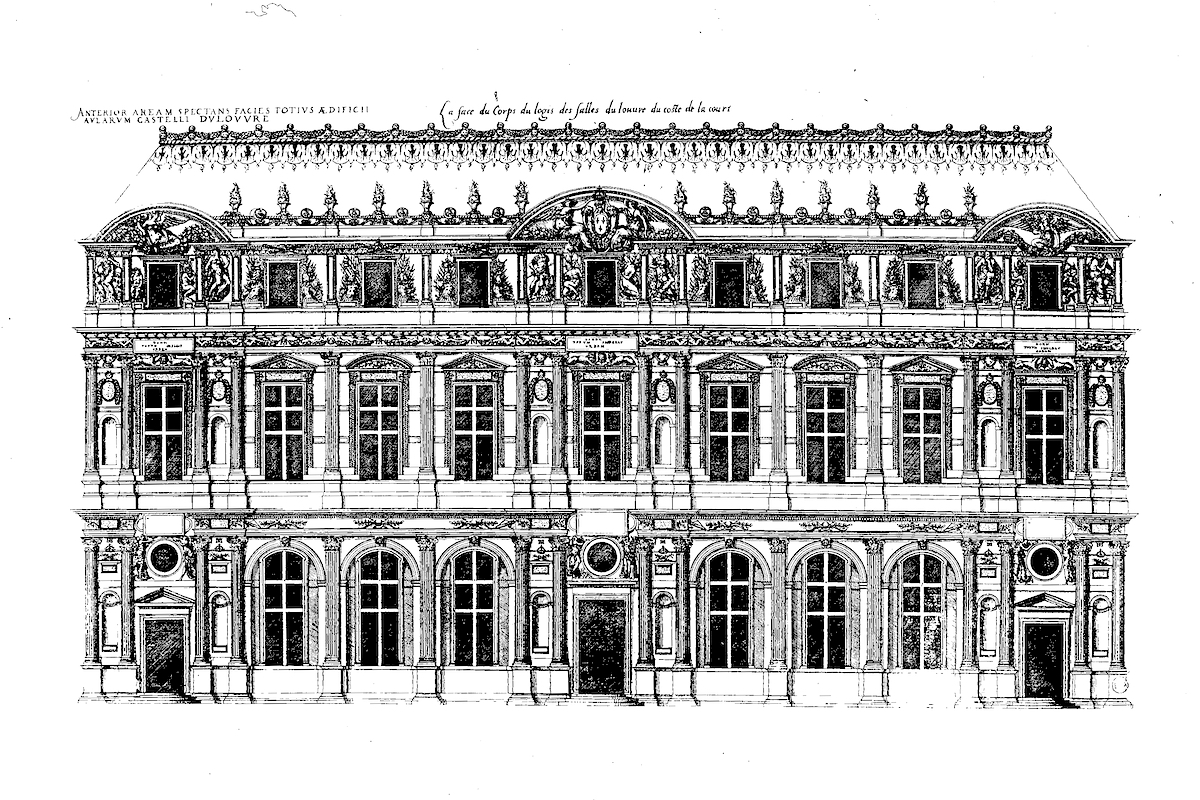

The rise and fall of Cristobal Balenciaga (1895-1972) embodies the changes that have occurred not ony in clothes but in culture in general over the last 100 years. The word couture began to be used in the 1920s. Christian Dior's (1905-57) ‘New Look’ in 1947 marked the beginning the '

golden age' of couture, brought to an end by the ready-to-wear revolution in the 1960s. Fitting neatly into this, Balenciaga began making clothes in 1917 and closed his house in 1968.

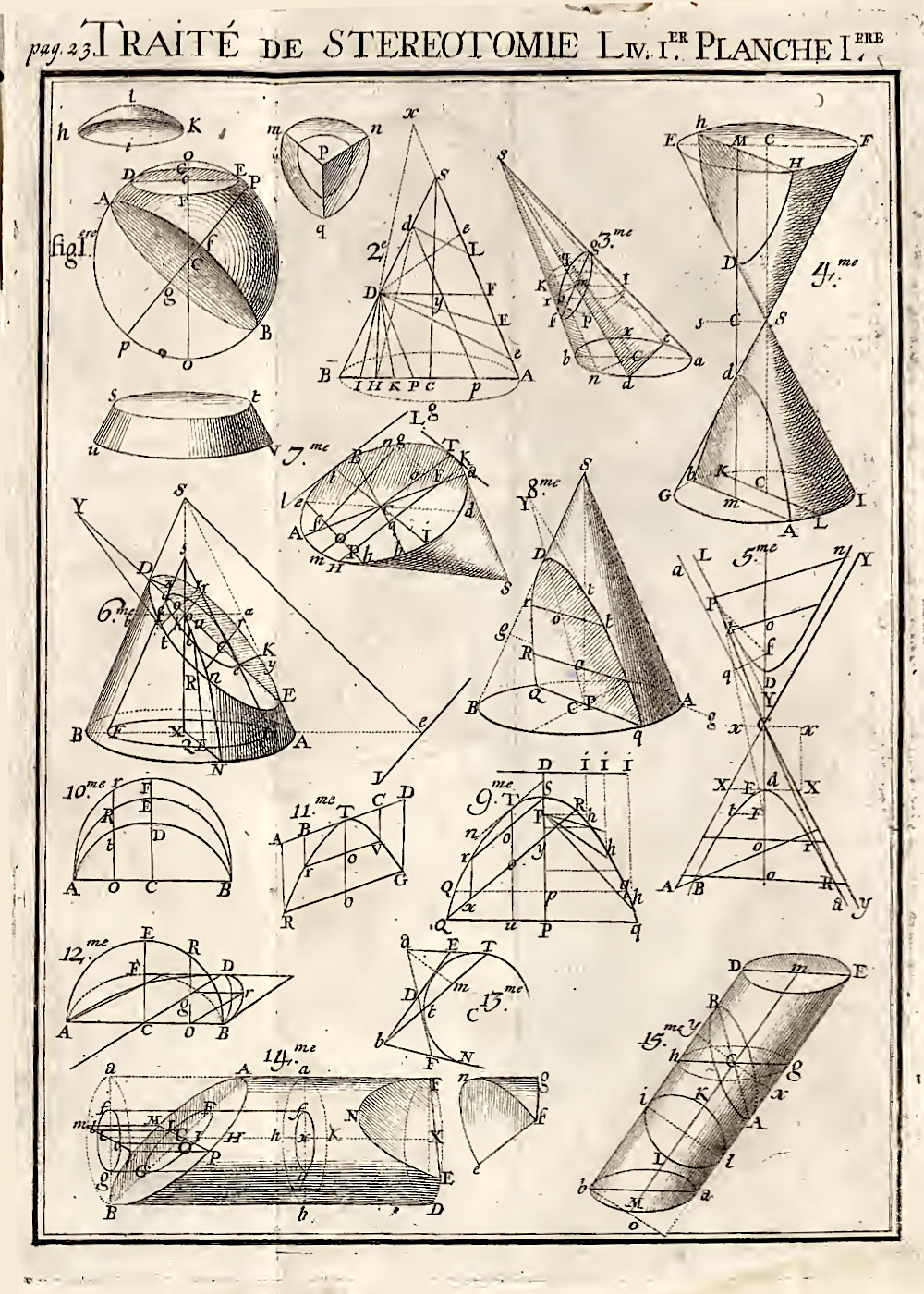

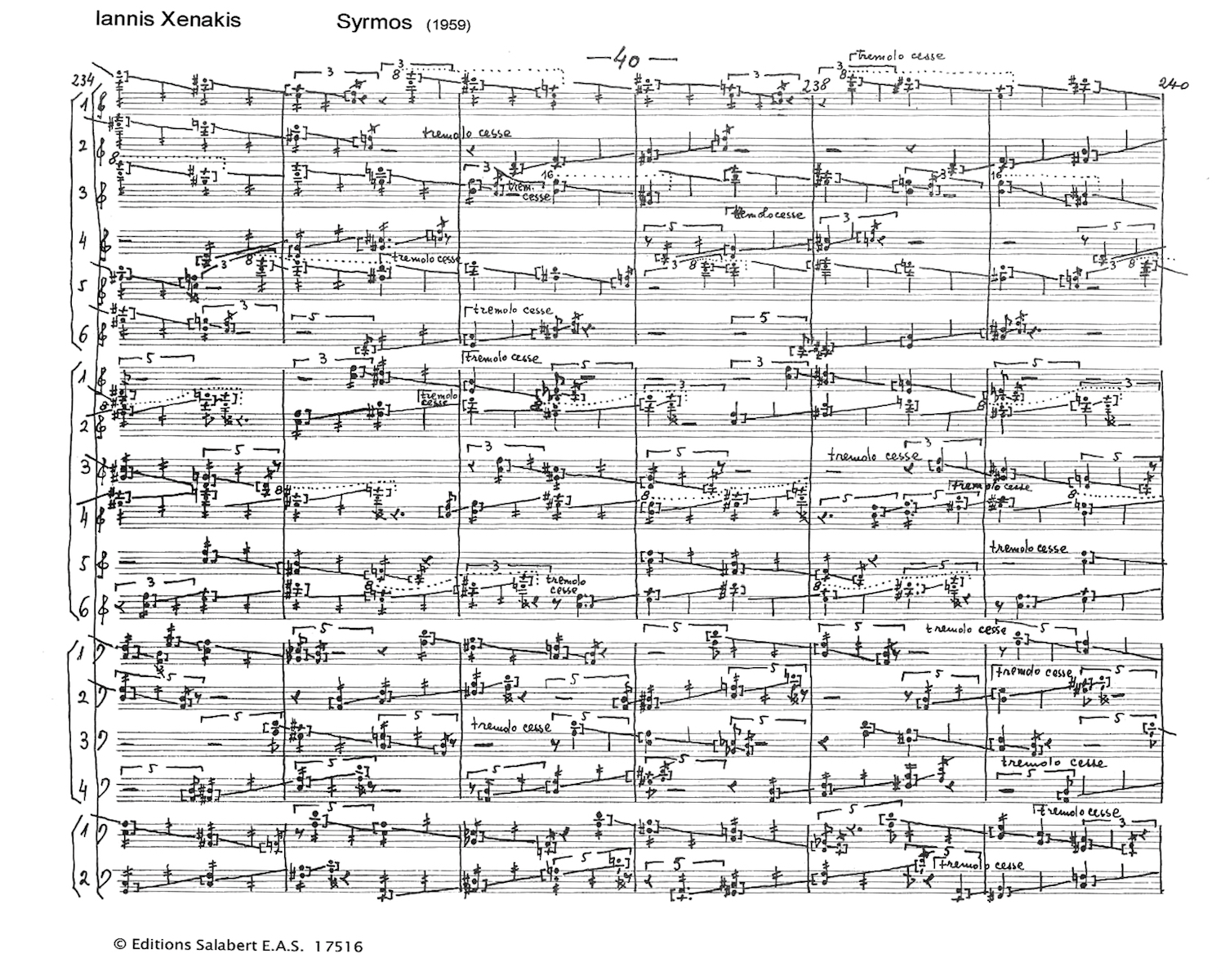

Cristobal Balenciaga was one of the greatest, if not the greatest, couturiers of the 20th century. He had an instinctive understanding of how to cut flat cloth to make sculptural forms. He preferred heavy weaves of linen, wool and silk that would hold their shape and colour over long periods of use. The level of skill he required in his couture house meant training and prestigious employment for large numbers of seamstresses. His genius was recognised by other great couturiers, of which one, Coco Chanel (1883-1971), was his equal:

Balenciaga alone is a couturier in the truest sense of the word. Only he is capable of cutting material, assembling a creation and sewing it by hand, the others are simply fashion designers.

It is commonly assumed now that couture was restricted to the few wealthy clients who could afford the personal services of the couturier. This is a serious misrepresentation, however: couturiers would license designs to be sold as paper patterns in department stores - to be copied with slightly less attention to detail and in slightly lower quality materials by seamstresses or at home - so that clients from a range of incomes and backgrounds could afford the designs.

Cristobal Balenciaga: Skirt Suit, 1954

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

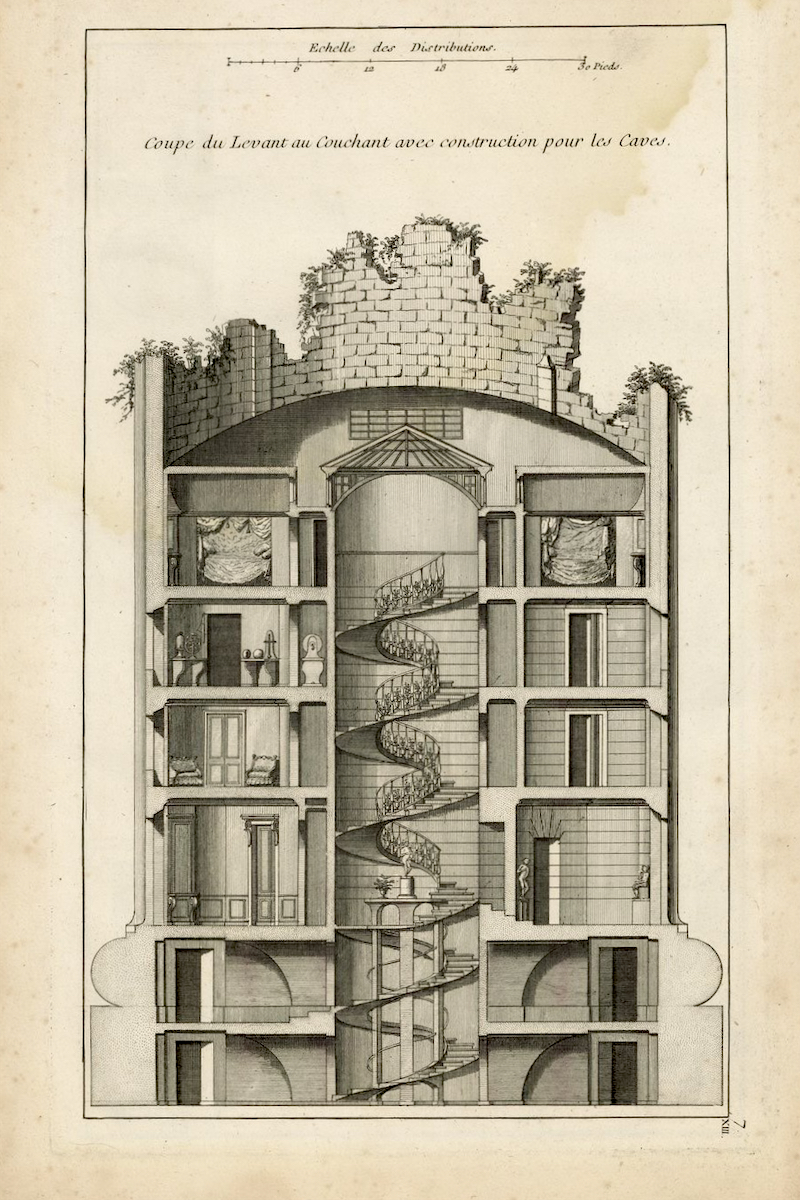

While his work after WWII was close to the ‘New Look’ of flared skirts and tight jackets, Balenciaga’s work became more abstract and sculptural. His

sack dress of 1957 began the trend for this new shape in the 1960s taken up by younger designers such as Mary Quant (1930-2023). The attention to detail and materials of these designers were comparable to diffusion lines as dressmaking skills were still commonly available. Of course these looks were then popularised by many others at lower levels of quality.

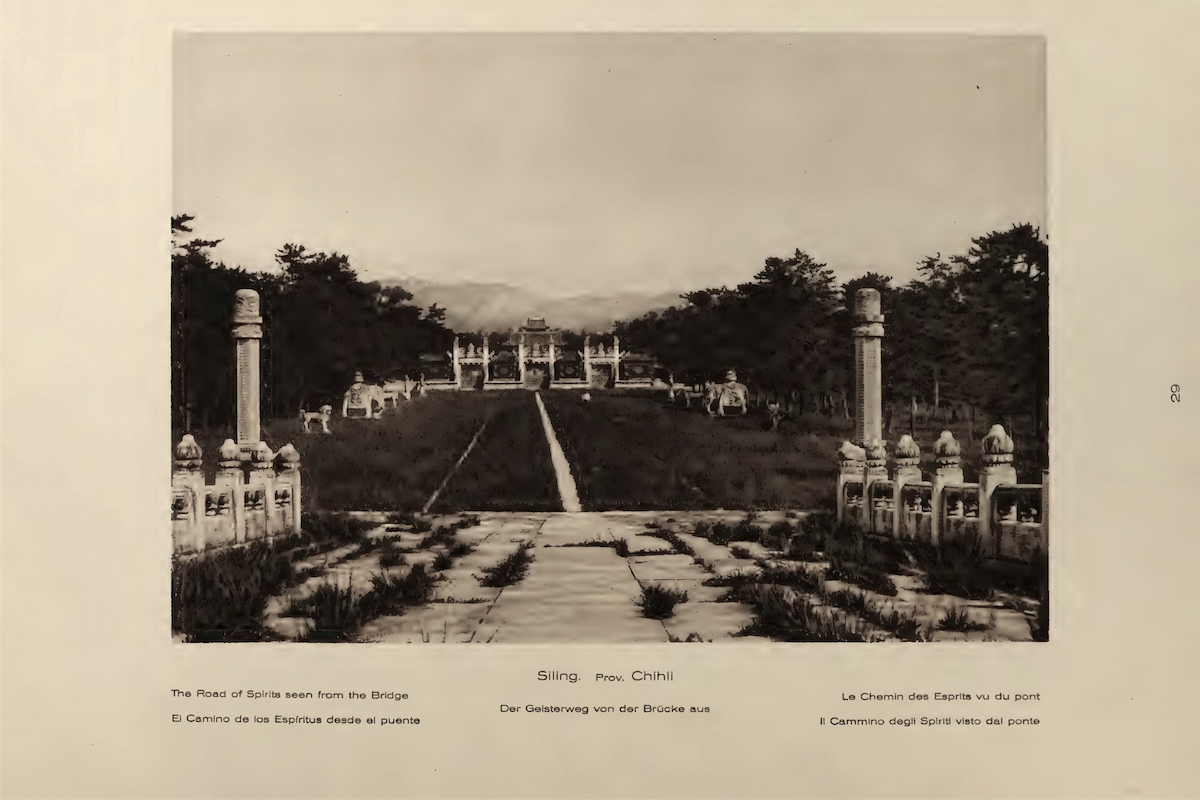

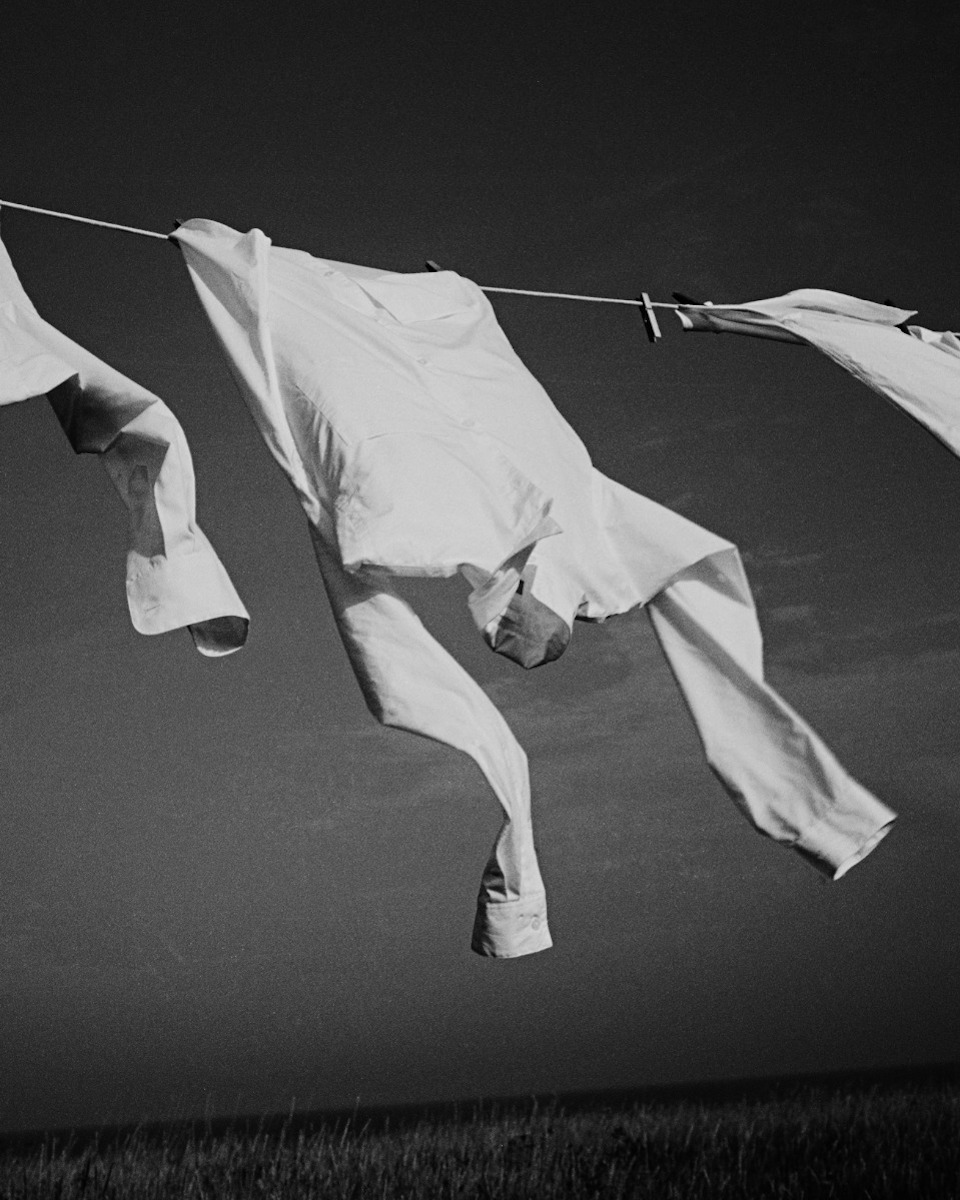

Balenciaga’s

Evening Ensemble of 1967, made for Gloria Guinness, is, without any doubt, one of the great works of art of the 1960s (Time magazine voted Gloria Guinness the world’s second ‘Best Dressed Woman’, after Jackie Kennedy, in 1962). Balenciaga developed the heavy woven silk material in conjunction with the manufacturer

Abraham Fabrics, Zurich, itself a victim of the ready-to wear revolution.

The V&A describes the construction of this dress:

The stiff woven fabric is vital to the success of this sculptural dress. Its appearance - a simple, slightly glistening cone - belies its ingenious cut and construction. The garment has been cut in one piece with three main seams - two short ones at the shoulders and one long one down the centre back. The boat neckline, which is scooped out at the back, fastens at the left shoulder with hooks and eyes. Dipping hemlines have long occupied designers and in this case maximum contrast is achieved by a knee height at the front and a ground trailing level at the back. Thus we have the best of both worlds, from one angle, a petite black dress, from another an impressively trained gown. The curved and weighted hem has a wide self-binding (seamed at regular points) and the train has a deep facing which adds to the rigidity of the dress. It was originally worn under a shorter cape in the same fabric which buttons at the front and echoes the clean and dramatic flared lines.

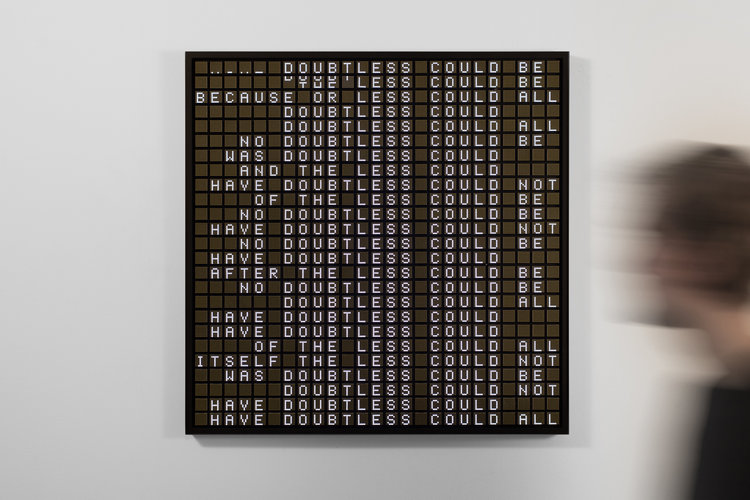

The advent of ready-to-wear brought about two fundamental changes. First, cloth became mass produced on high speed looms, much at low quality; cutting usually became optimised to maximise the yield from the roll of cloth; producers began to copy styles that were cheap and easy to make and sell; clothes were sewn in sweatshops in low-wage countries with a minimum of skill. I do not know to what extent the present house of Balenciaga use or endorse these practices, but the results are a very long way from the original artistic or technical standards.

Second, the concept of what constitutes quality in clothes has changed. Balenciaga’s clothes were not intended for personal display as we understand that concept today. The values of beauty and elegance have been replaced by vulgarity and ostentation. The idea of stamping a logo on what are, quite frankly, everyday clothes in everyday materials to increase their ‘worth’ would have been incomprehensible to Balenciaga.

Much of Balenciaga’s work is in copyright. Great collections are held at the

Cristobal Balenciaga Exhibition, V&A, London 2017

The work immediately after WWII was close to the 'New Look' with tight skirts and jackets. As with Dior the materials and cutting are superb.

© Thomas Deckker 2017

After the 'New Look' in the 1940s Balenciaga began to experiment with shapes made with very simple cuts. This display shows dresses of increasing daring.

© Thomas Deckker 2017

At the height of his classic period in the 1950s Balenciaga made dresses with extraordinary grace and form.

© Thomas Deckker 2017

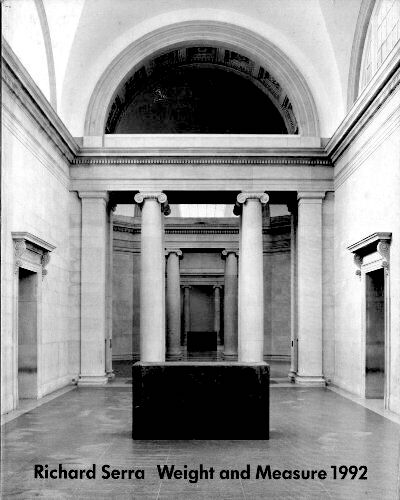

During the 1960s Balenciaga began to experiment with sculptural shapes cut from single pieces of cloth with minimal seams.

© Thomas Deckker 2017

Balenciaga's strong colours and shapes in the 1960s were an inspiration to designers like Mary Quant, with her

'Peachy' dress and 'Minimalist Mini' shown here.

© Thomas Deckker 2017

Thomas Deckker

London 2020