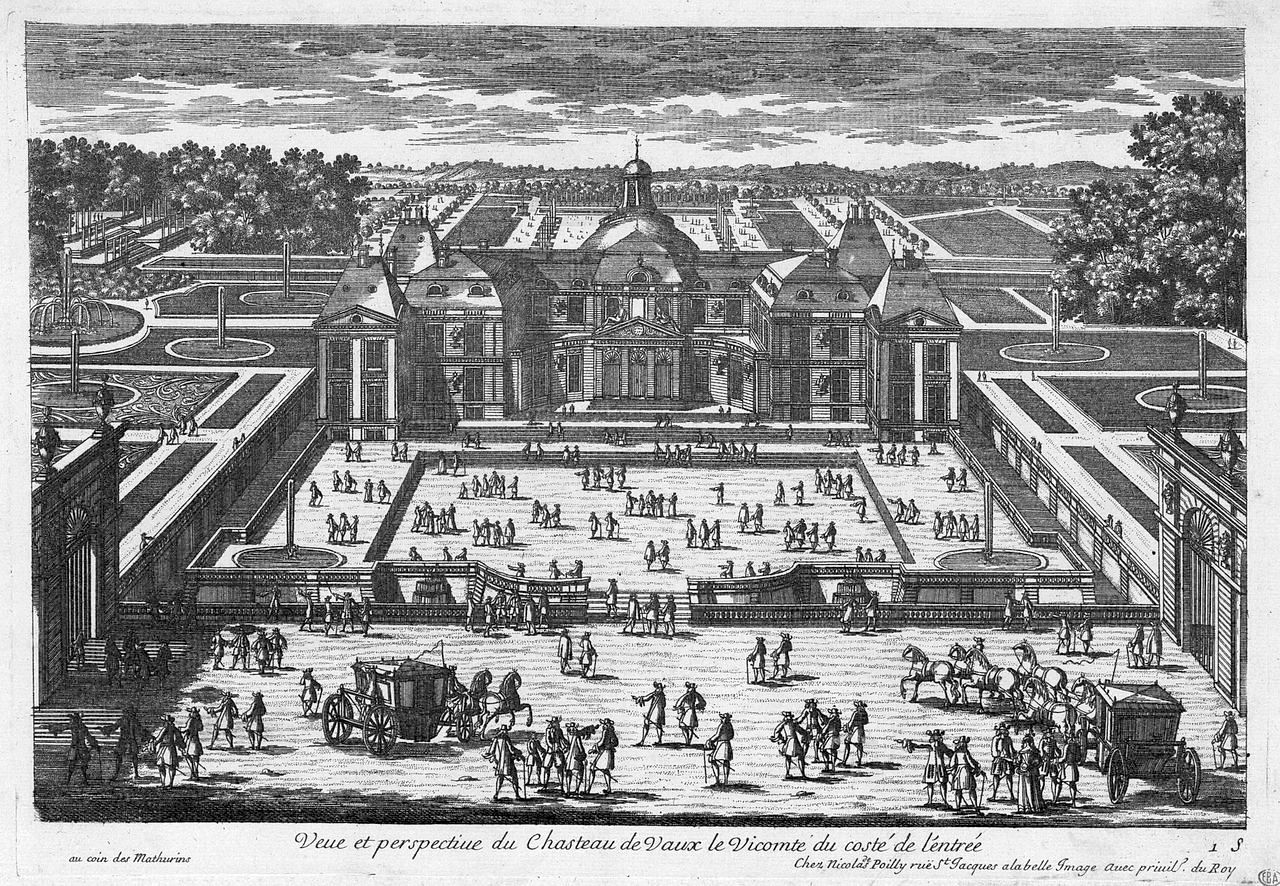

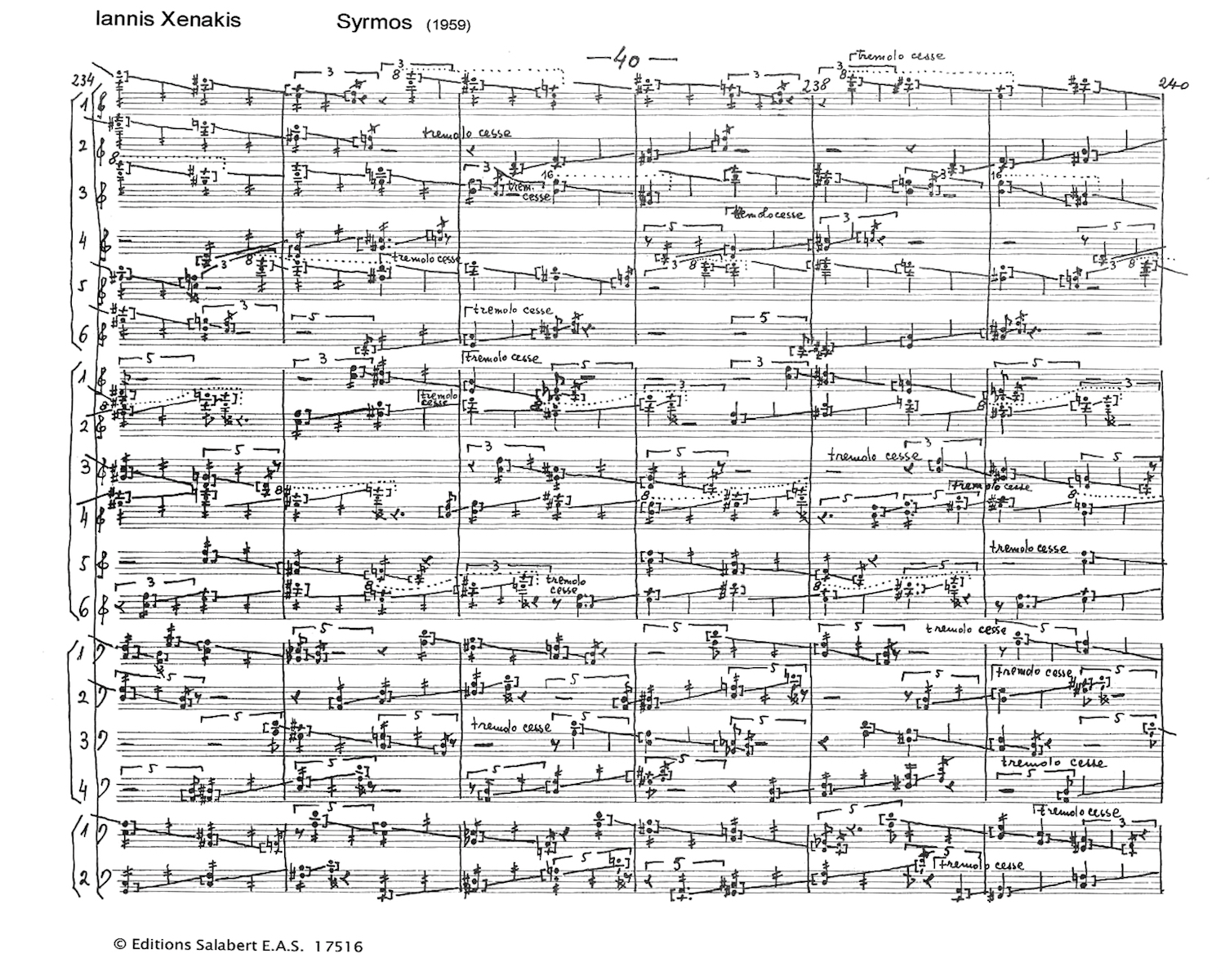

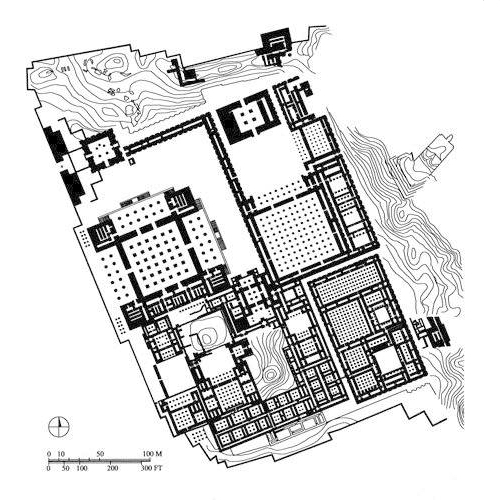

Plan, Palaces of Darius and Xerxes, Persepolis, Iran

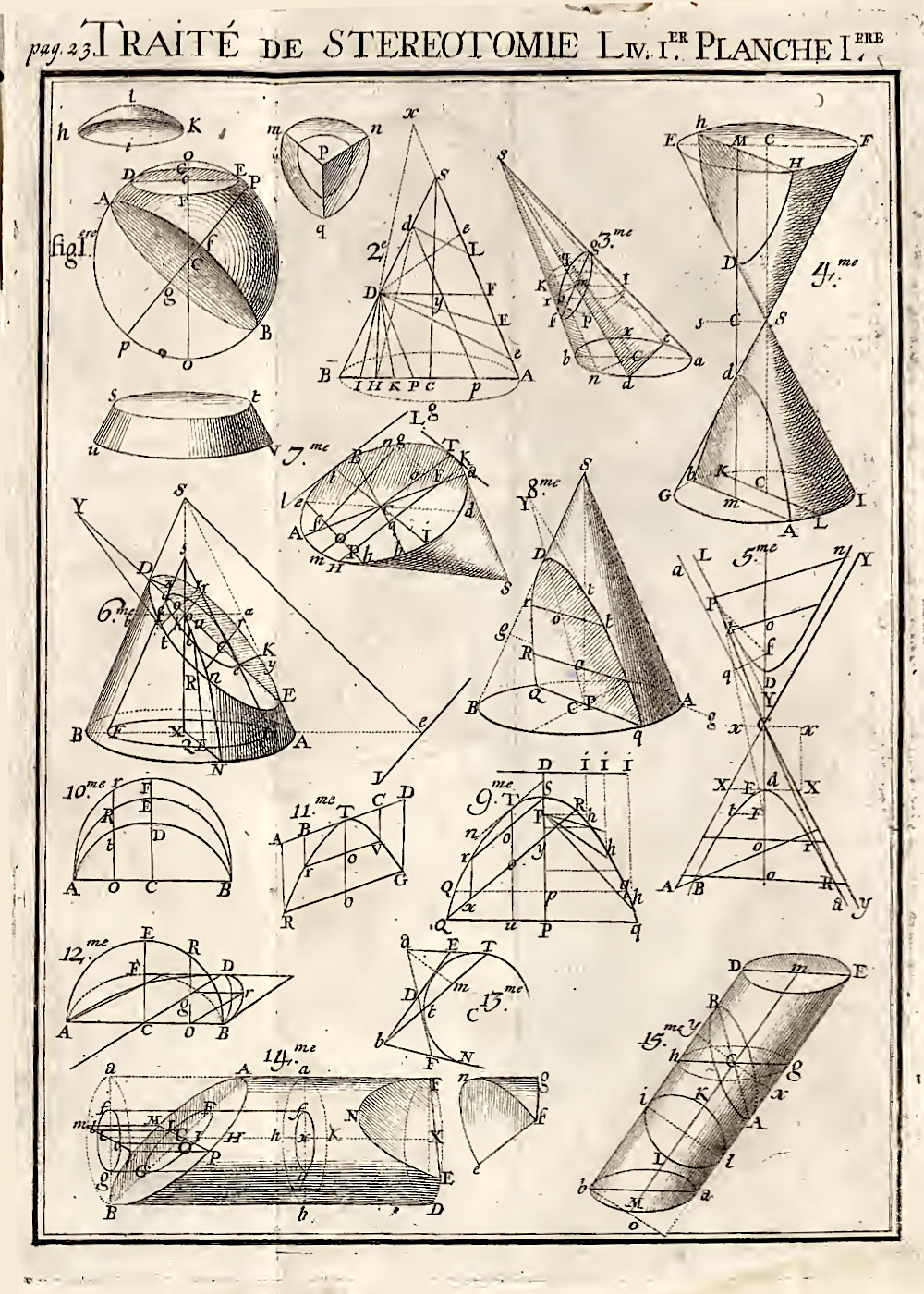

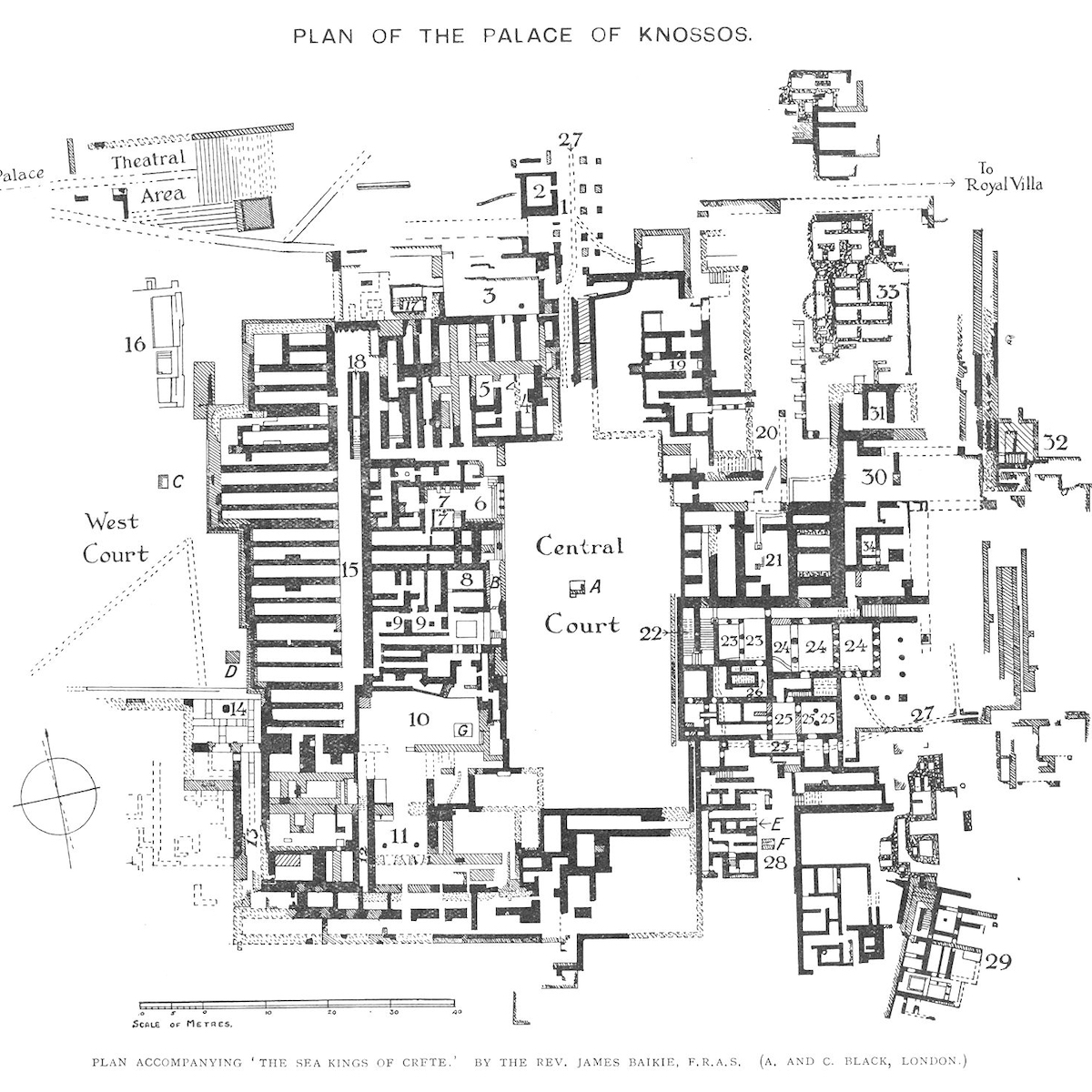

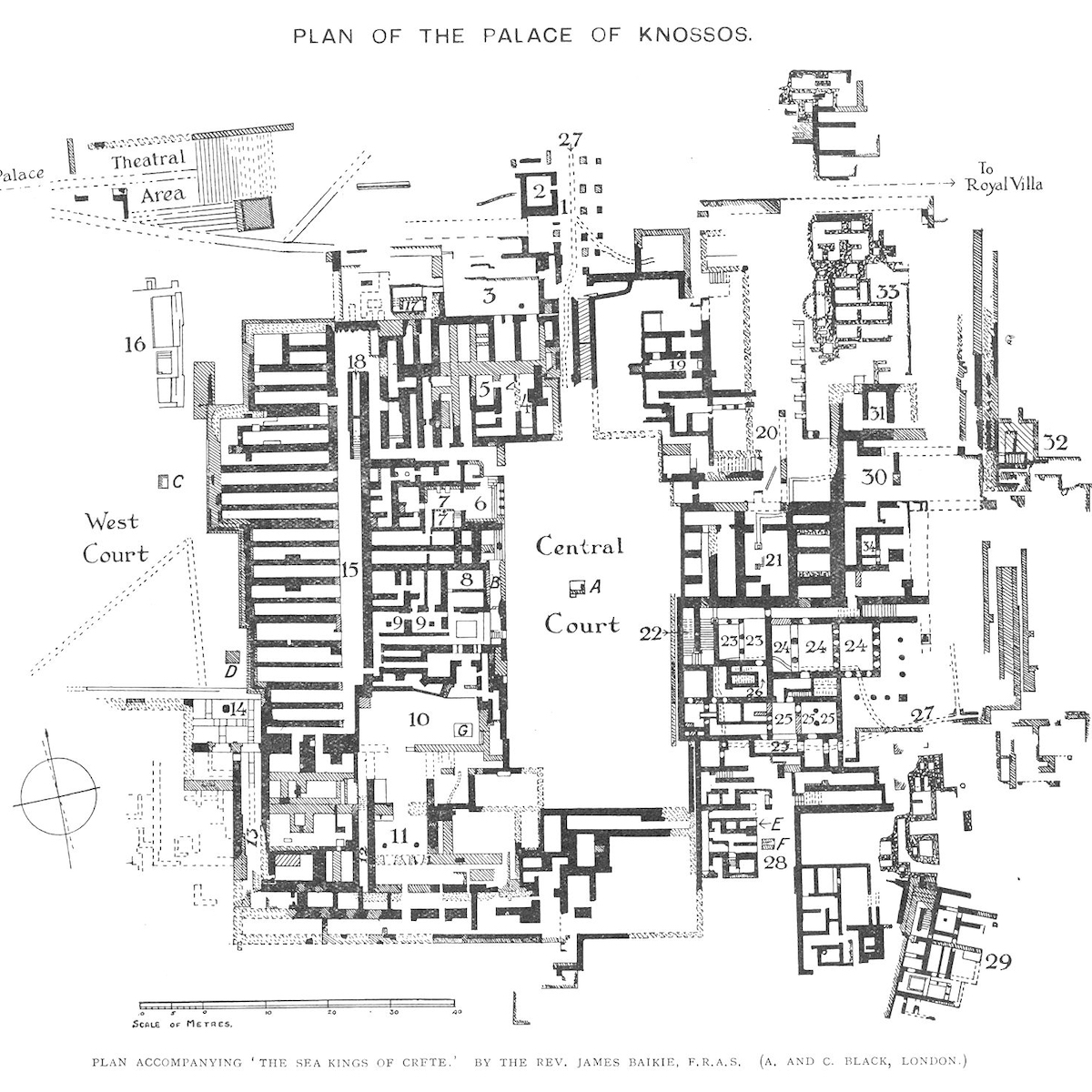

The Plans of Antiquity

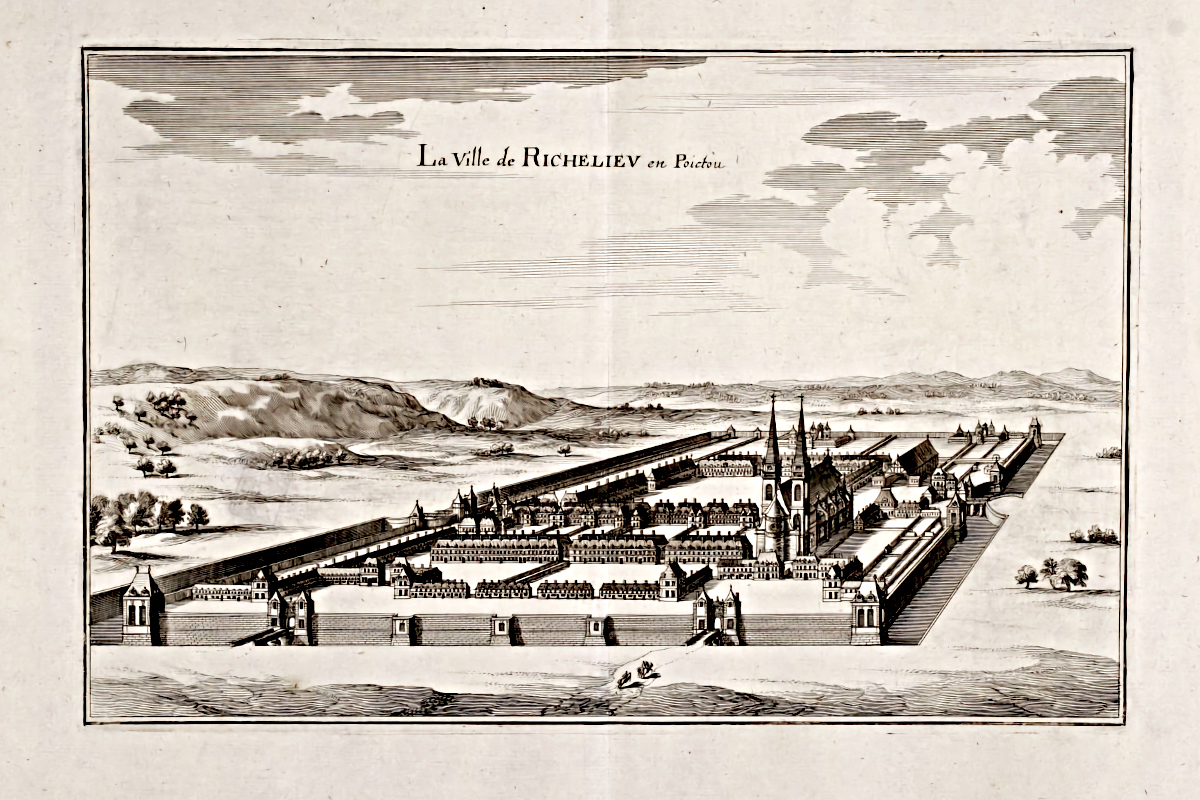

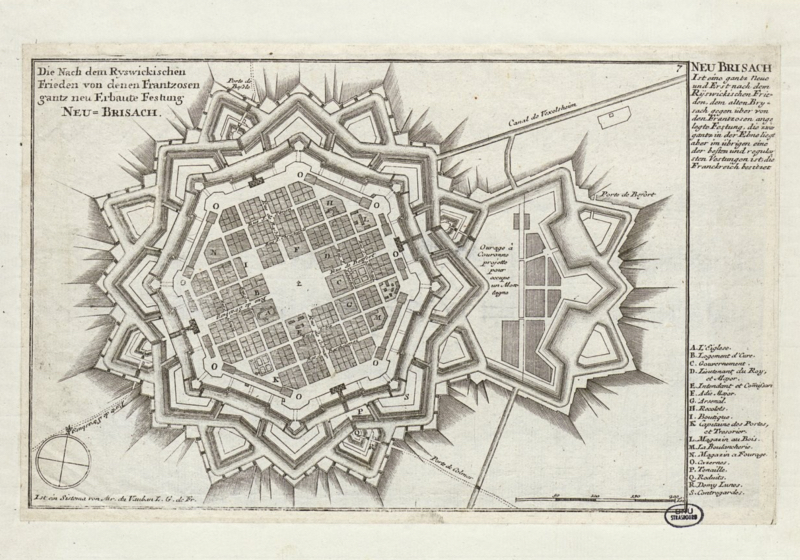

I was fascinated, as a child, by the plans of buildings in Antiquity, which I found in reference books in my nearest public library, the

Saskatoon Public Library. These plans allowed my imagination to roam through, and recreate, unknowable and sublime spaces. Despite archaeological research, our understanding of how these spaces were conceived and perceived is, with the exception of the very few that may be clearly identified, speculative. I did not think it extraordinary, at the time, to be able to read a plan.

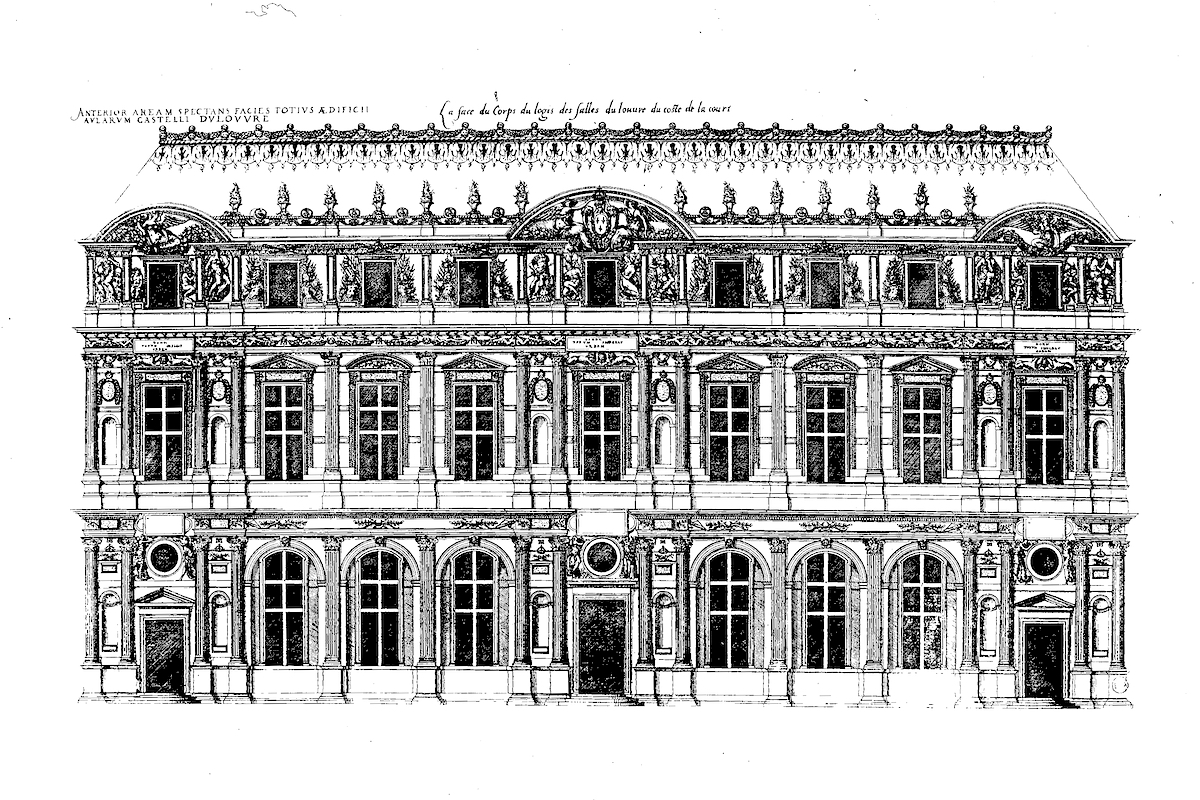

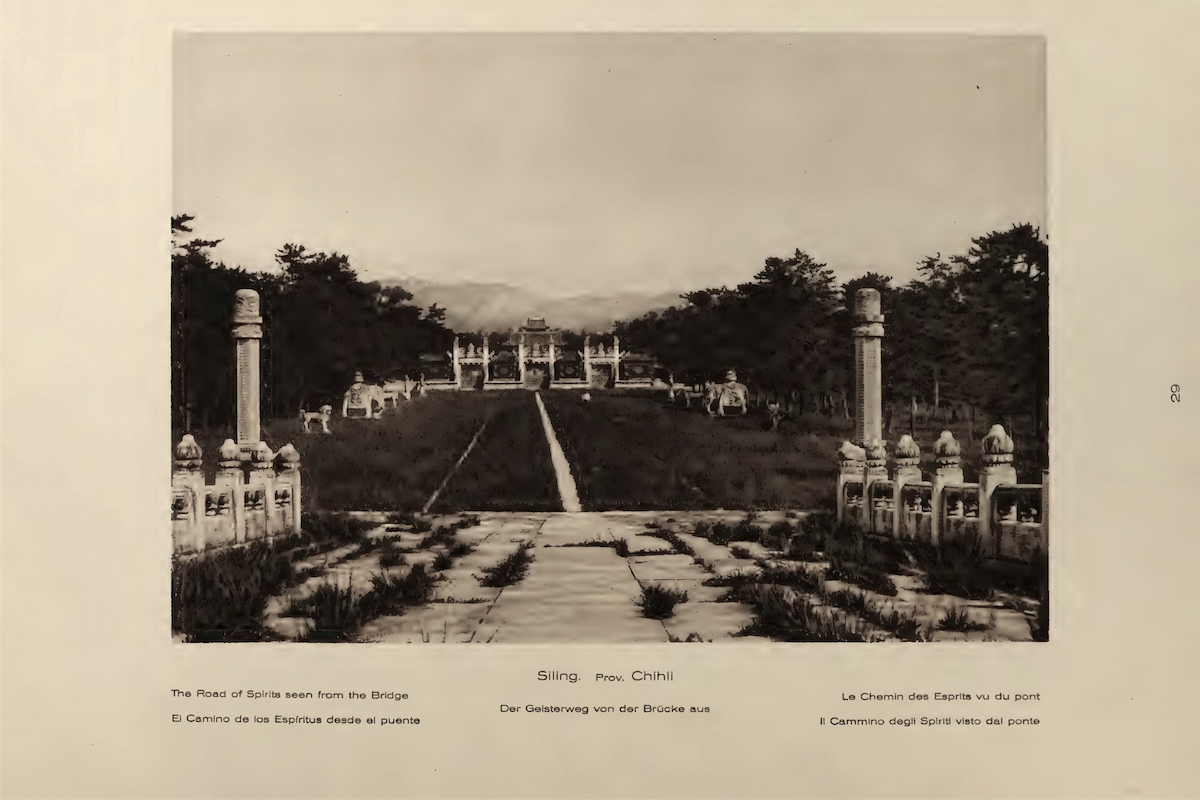

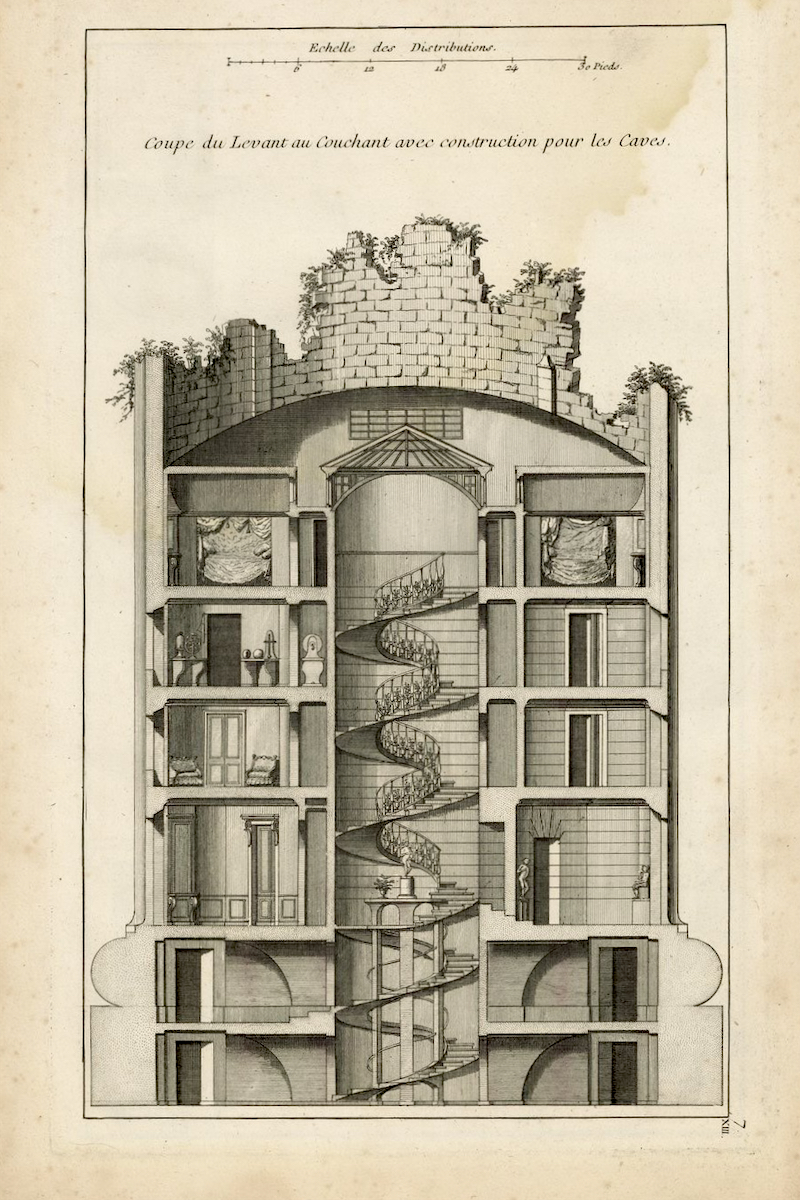

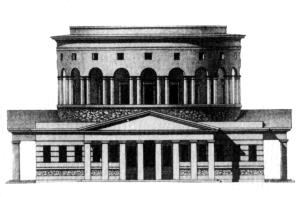

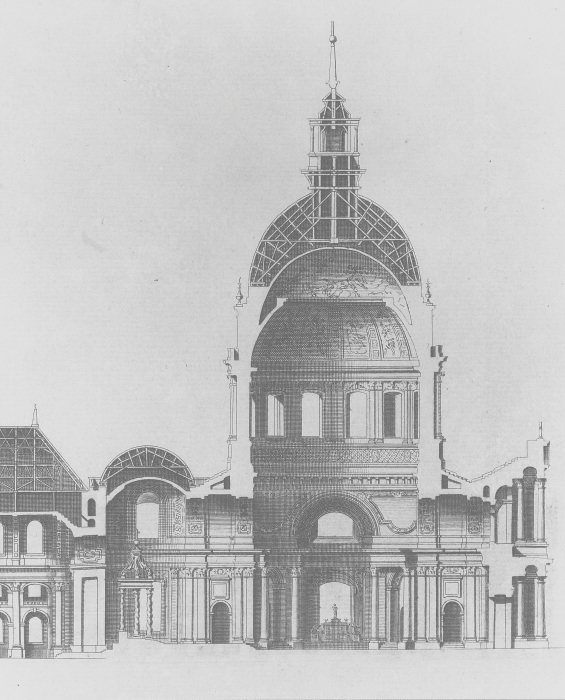

We now associate the scale and drama of these spaces with the sublime, especially as they have absolutely no religious or social significance to us. The sublime, as a critical category, came into being at the end of the 18th century, at the end of the classical period and the beginning of modernity. In 1756 Edmund Burke, in

The Philosophical Enquiry into the Origins of Our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful identified the aesthetic response of the sublime as more powerful and direct than pleasure, which he believed was derived from conventional ideas rather than direct experience. The sublime appeared in architecture at the time in the work of Étienne-Louis Boullée and Claude-Nicolas Ledoux. The fascination with the sublime is demonstrated clearly in Percy Bysshe Shelley's 'Ozymandias', written in 1818:

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said — “Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies...

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

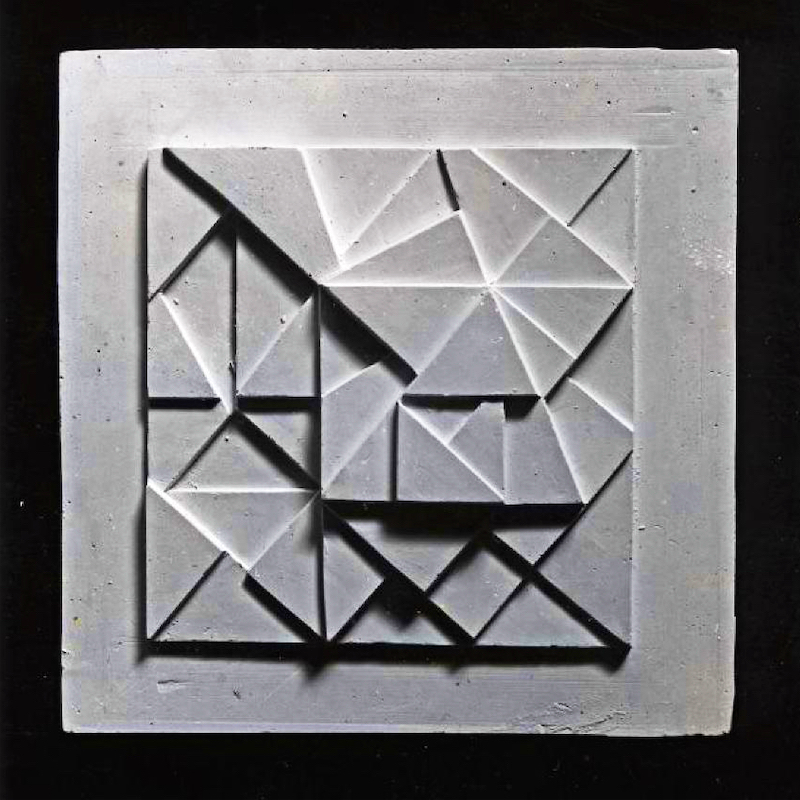

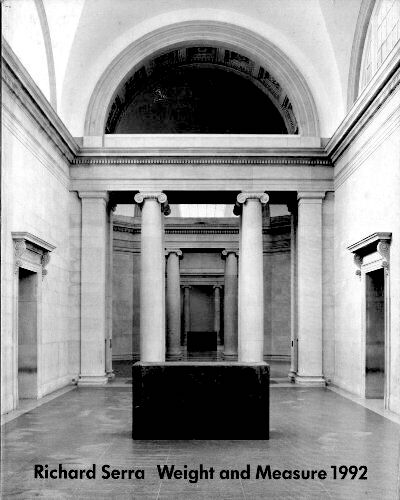

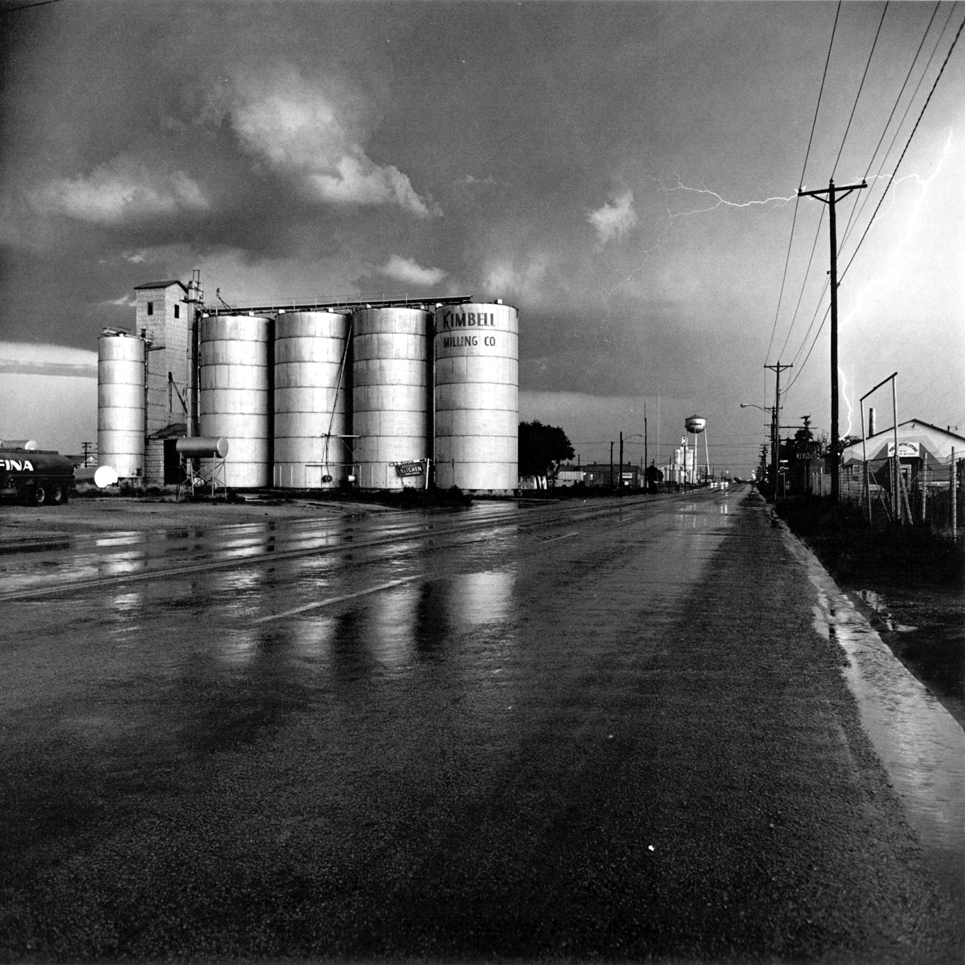

The sublime, of course, is a central concept in our appreciation of the work of

Tony Smith,

Donald Judd and

Frank Gohlke in contemporary art and Steve Reich and John Luther Adams in contemporary music. These works appeal directly to the emotions, and do not rely on historical precedents of beauty. They recognise that there is no common iconographic language that transmits social ideas - whether about art, landscape, architecture or music - in the modern age.

In my article

'Architecture and the Humanities' for

arq [Cambridge University Press 2014], I described the common view in the Humanities (put forward by organisations such as the British Academy in their publication

Past Present and Future: The Public Value of the Humanities & Social Sciences) that architecture was not worthy to be considered part of the Humanities, although archaeology was. As professions, of course, archaeology and architecture do not have many practices in common, but as intellectual disciplines they are linked through buildings and the social use of space. As I wrote in my article:

Architecture gives form to self and society, but this is rarely acknowledged in the humanities and social sciences although architectural concepts are central to discourses of other disciplines.

I maintained a fascination with both ruined buildings and with plans throughout my career as an architect. I was fortunate to have visited the palaces of Darius and Xerxes even before I became a student of architecture, but sadly did not use a camera at that time. This is inconceivable in today's world of smartphones, but perhaps more understandable in the days of film cameras.

These reference books may have been two Pelican History of Art titles: Stevenson Smith: Art and Architecture of ancient Egypt (1958) and Henri Frankfort: The art and architecture of the ancient Orient (1954) although the exact titles elude me. Sadly these Pelican History of Art titles have not been continued in print by Yale University Press, who took over this series. I am grateful that I saw these reference books while it was still considered acceptable for serious publications to be available in local libraries. I am not sure that I would have found a more populist book such an incentive to my imagination.

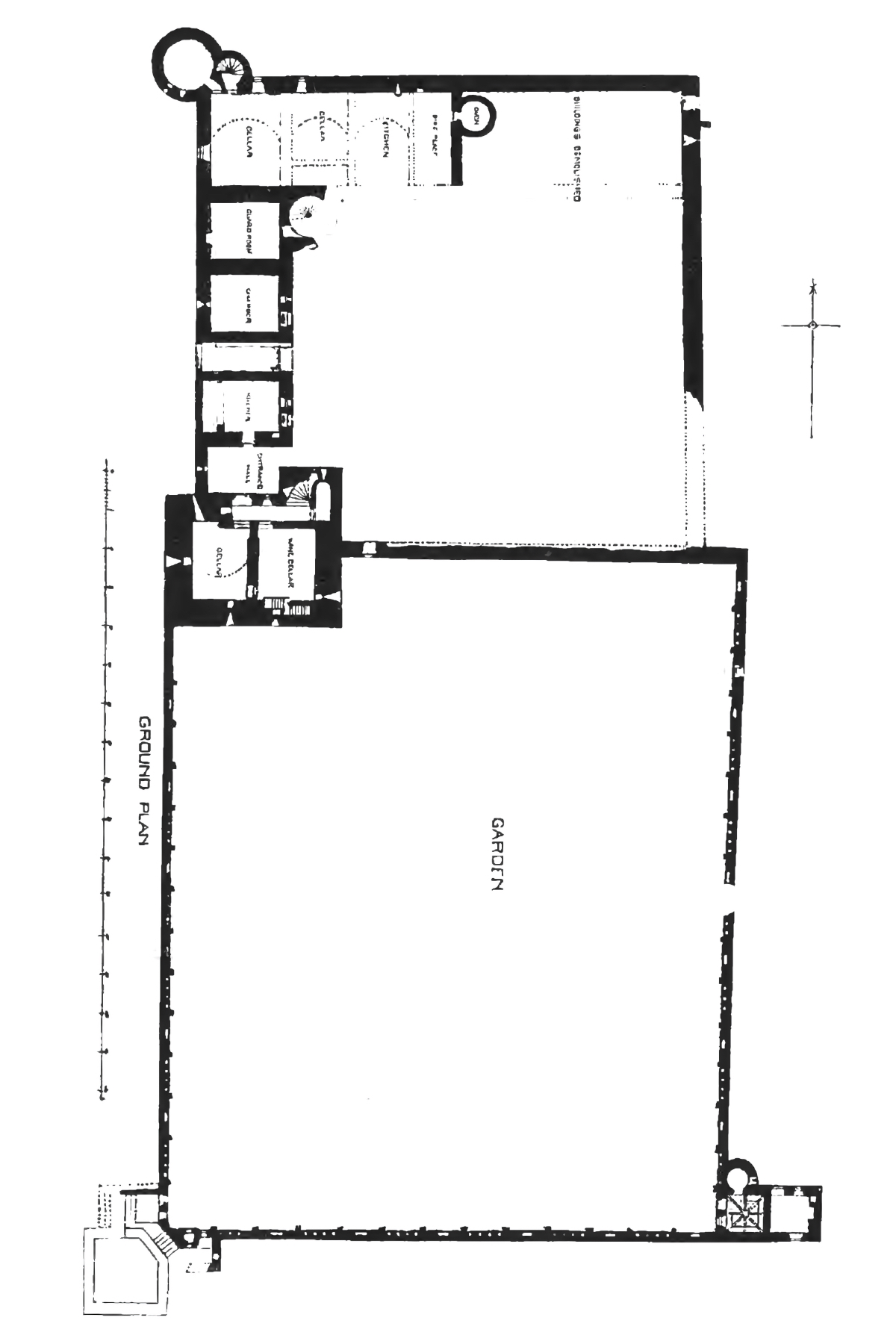

Plan, Palace of Knossos, Crete

Thomas Deckker

London 2020