thomas

deckker

architect

critical reflections

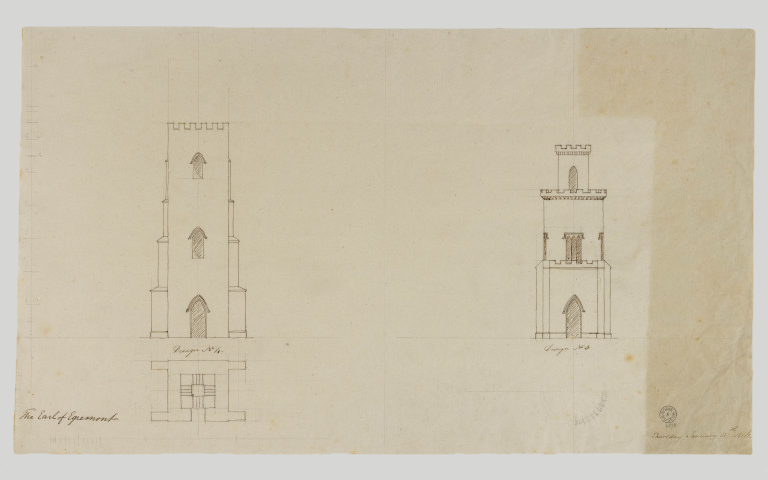

The Upperton Monument, Petworth

2022

2022

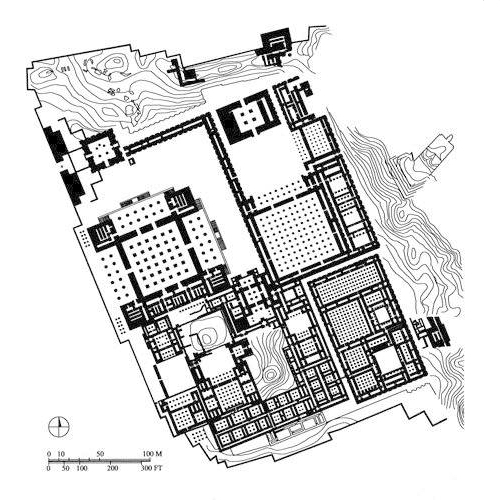

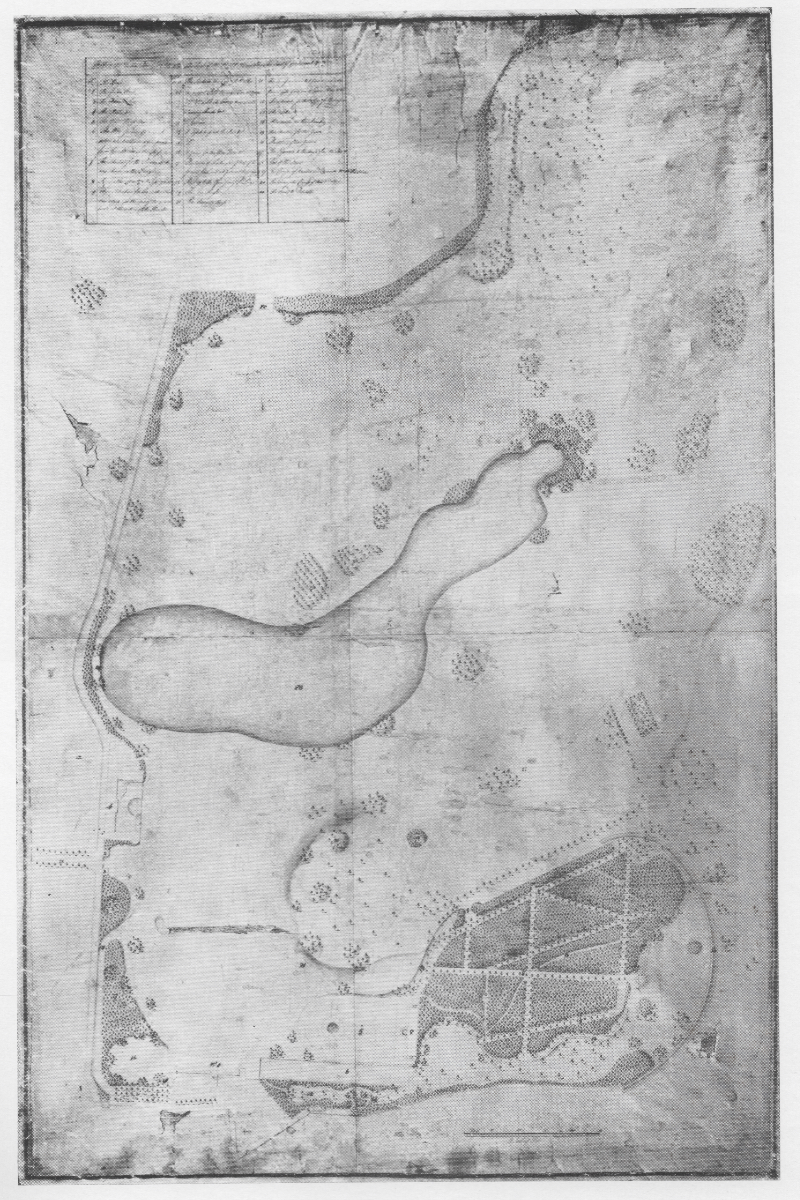

Capability Brown: Plan for Petworth Park

from Dorothy Stroud: Capability Brown

from Dorothy Stroud: Capability Brown

roll over for location of the Upperton Monument

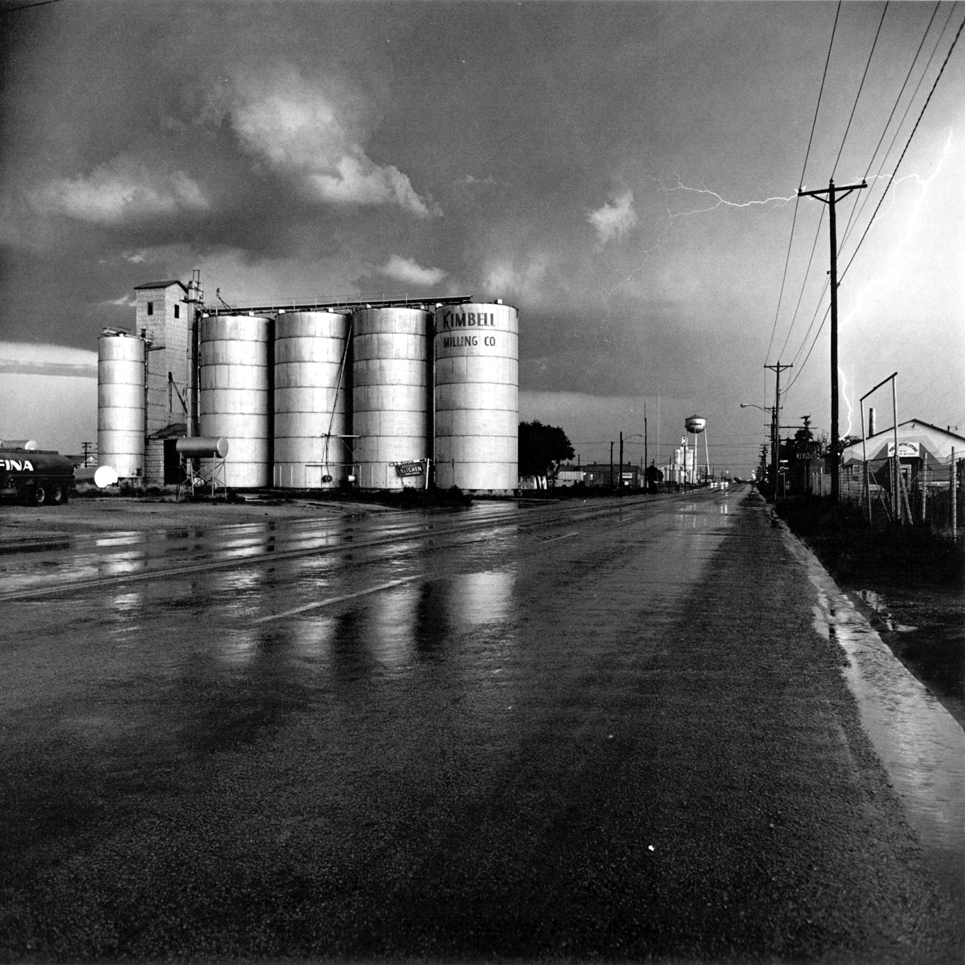

The Upperton Monument, Petworth Park

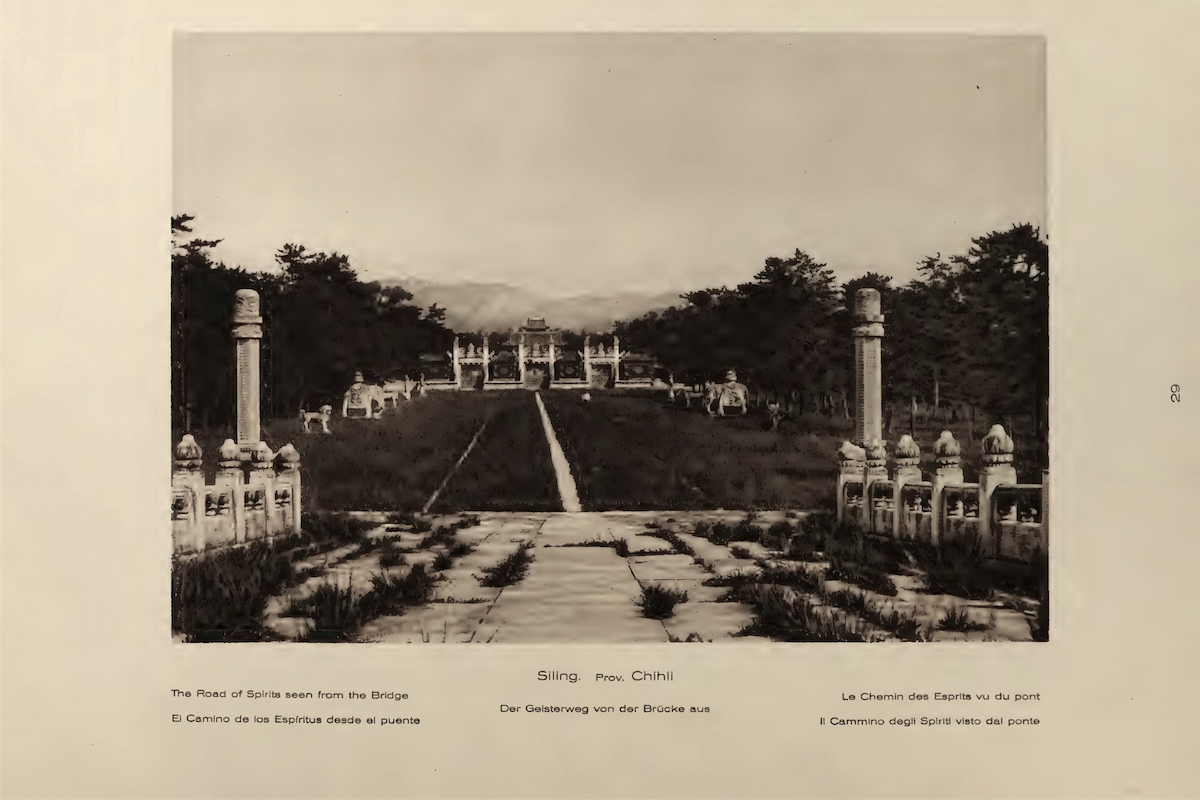

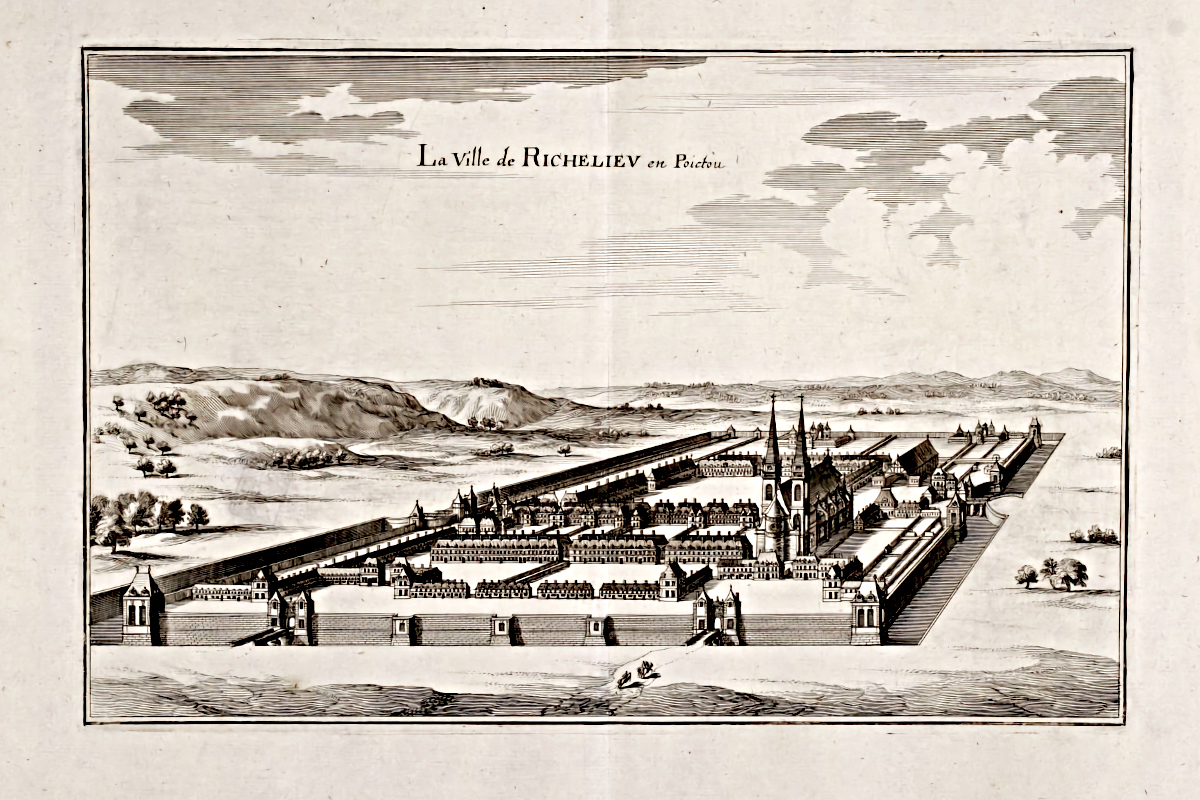

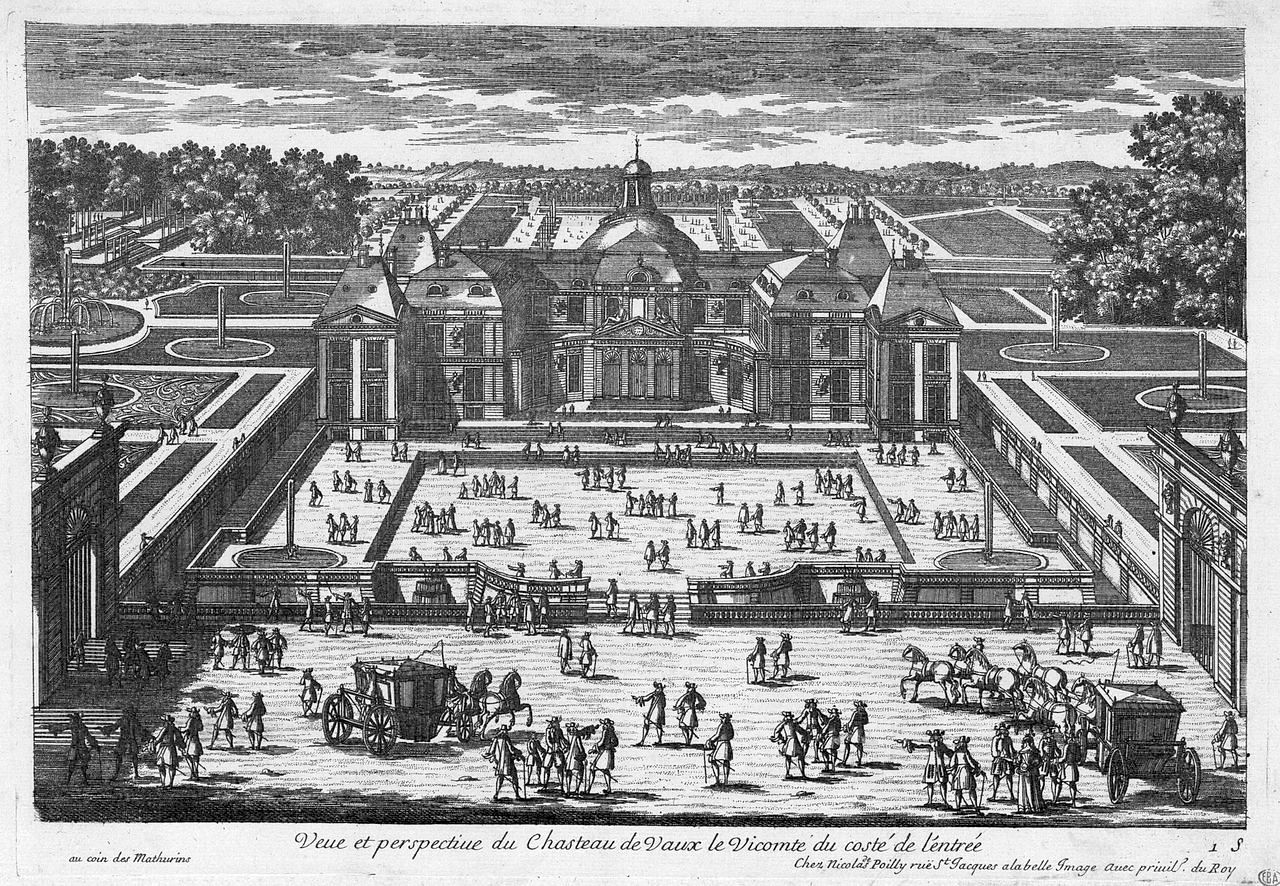

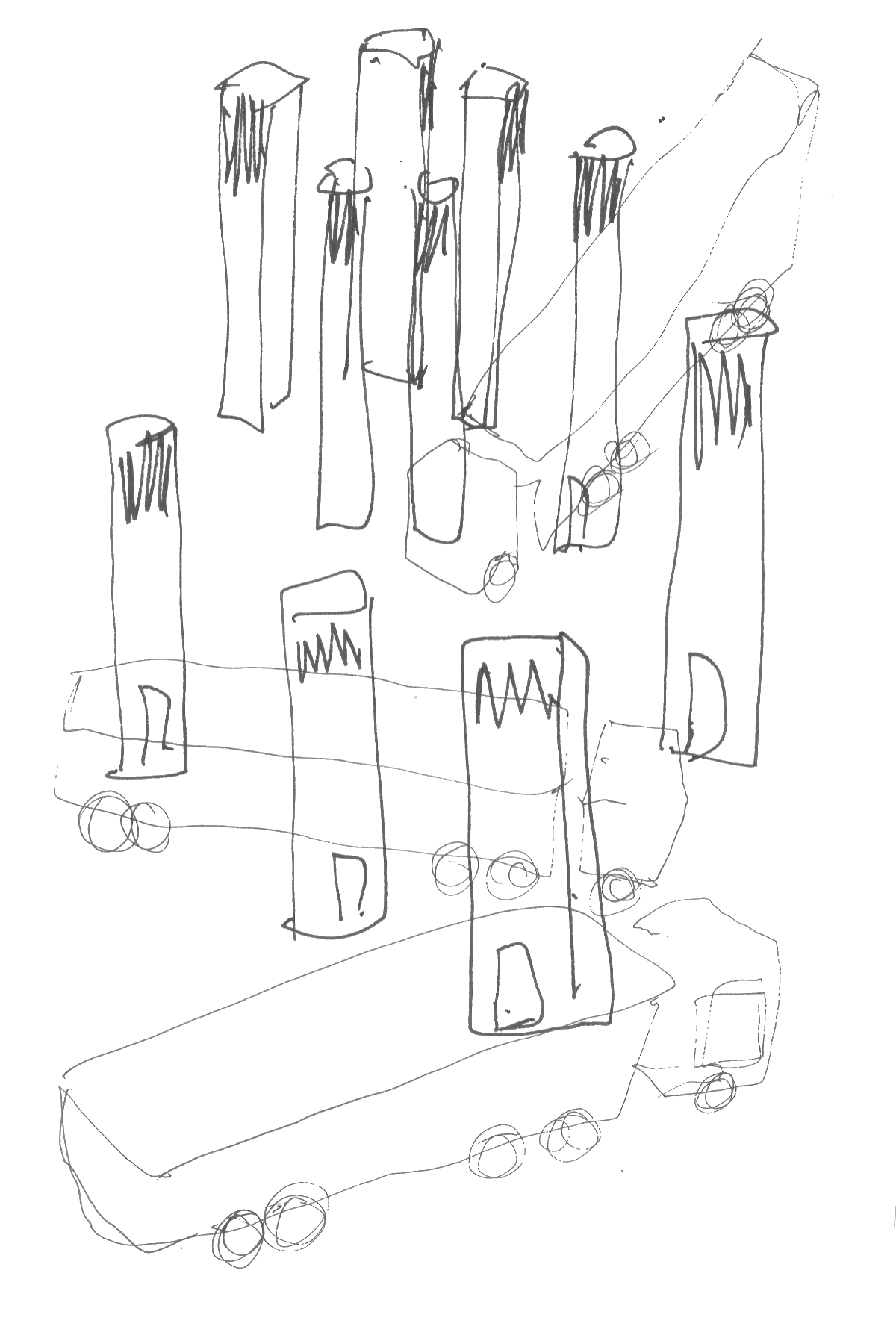

I was interested to come across the Upperton Monument in Petworth Park, as it was sited exactly how I saw my own project for a tower house. The Monument appears as a geometric object in a naturalistic landscape, a schema that recalls the paintings of the 17th-century French artist Claude, whose idealised visons of the Roman campagna became admired by landed collectors during the 18th century in England; the Petworth collection holds 'River Landscape with Jacob and Laban and his Daughters'. Many of Claude's paintings ended up in the National Gallery, which holds my favourite: 'The Enchanted Castle'.

Claude: Landscape with Psyche outside the Palace of Cupid ('The Enchanted Castle') 1664

© London: National Gallery NG6471

© London: National Gallery NG6471

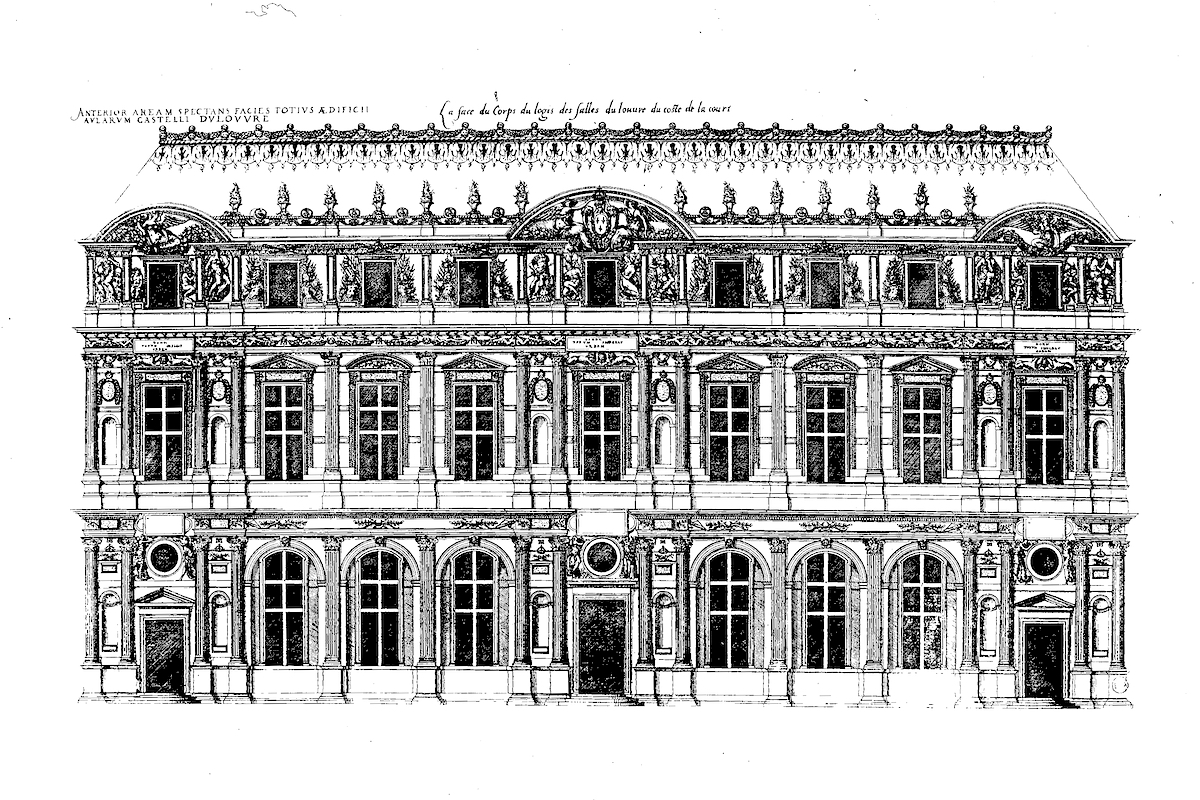

The gardens in their present form were laid out by 'Capability' Brown between 1751 and 1763. While 'Capability' Brown, according to the authoritative Dorothy Stroud (in Capability Brown, London: Faber 1974) had no particular interest in Claude, we can see in his meteoric career a happy confluence of his exceptional ability for arranging large landscape spaces and the desire of the upper classes to symbolise and embody the idyllic Roman campagna in a native form.

The Upperton Monument, Petworth Park

© Thomas Deckker 2021

© Thomas Deckker 2021

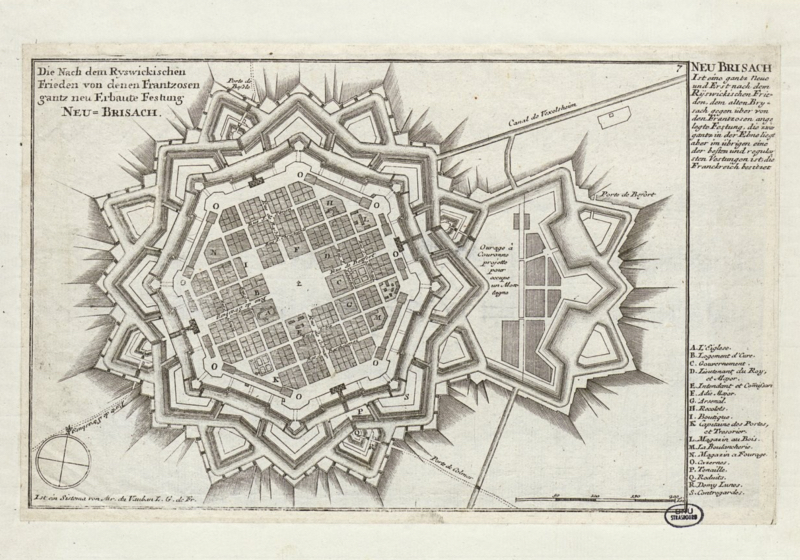

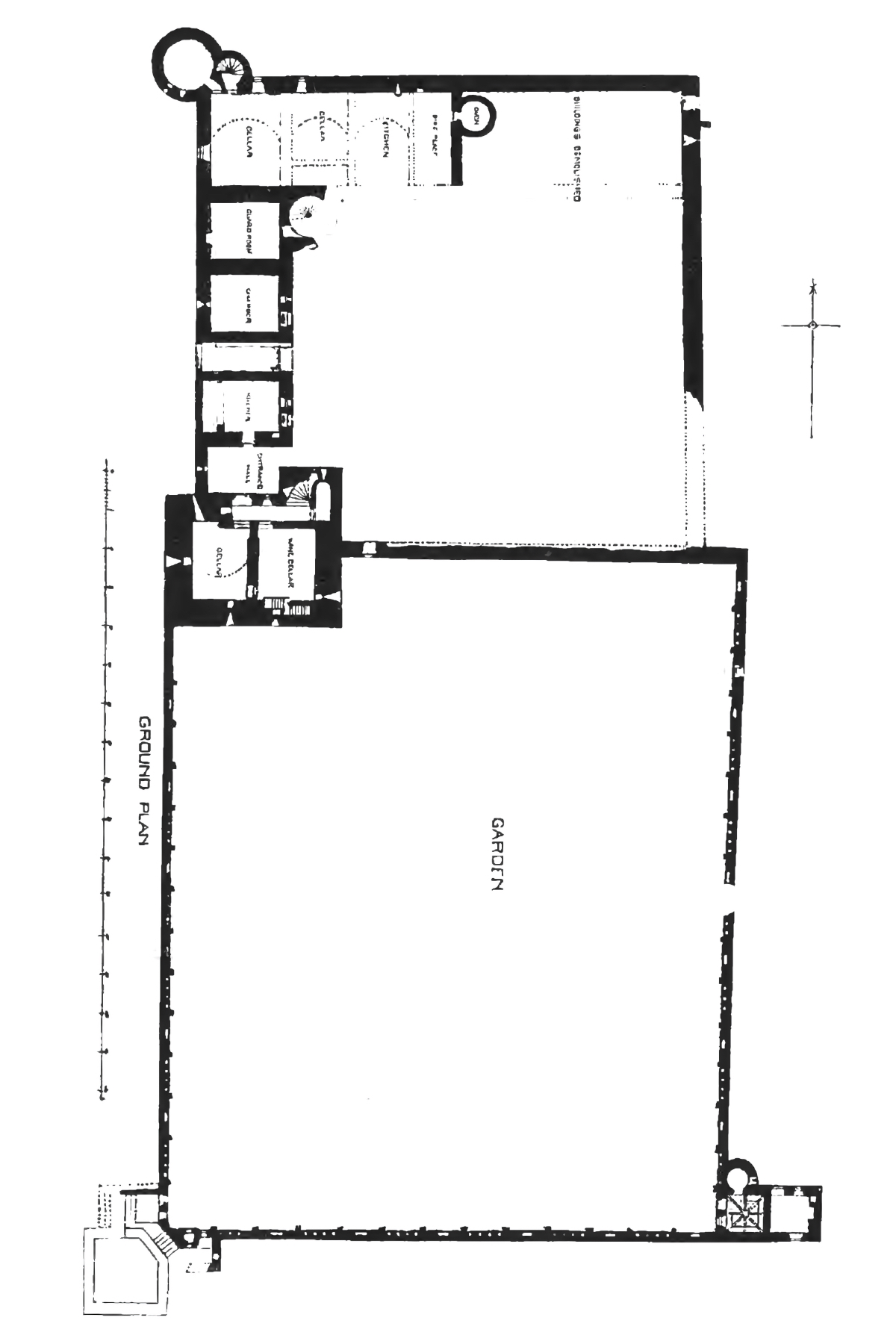

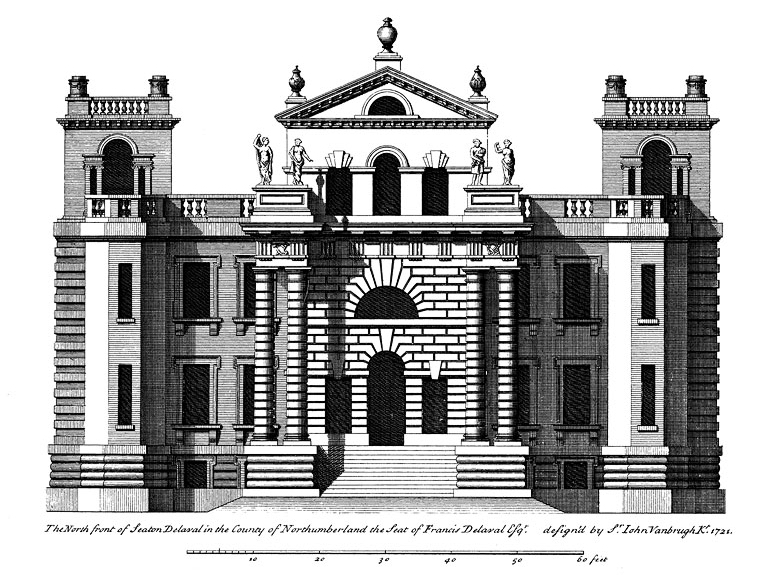

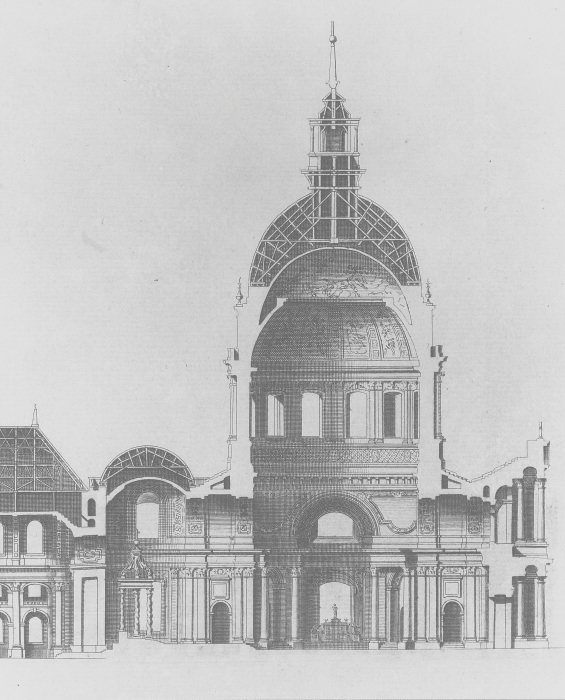

Ian Warrell (in the Tate Gallery publication Turner: The Fourth Decade Watercolours 1820-1830, 1991) suggested that the Monument be attributed to Sir John Soane, on the basis that Soane made designs for the North Gallery in Petworth House in 1820. Neither Soane's designs for the North Gallery nor the Monument seem to have been carried out. It is more likely that the Monument was by designed and built by 'Capability' Brown himself as an integral part of the landscape. The location may possibly be identified on his design drawing of c. 1753. 'Capability' Brown had of course started to design buildings in a gothic style, as may be seen at, for example, the contemporaneous stable block at Burghley. For the avoidance of doubt, the Monument was not built as a farmhand's residence, as there is a one identifiable as such nearby, and was probably built as a gazebo from which to admire, as well as adorn, the landscape. The site for the Monument is well chosen: on a ridge overlooking the valley and lakes, yet sheltered by trees to the north to make a distinct area around the house ('garden' would be an optimistic description). The cubic form of the building shows its roots in classical architecture, while the gothic details thinly drawn over the quite regular facade is typical of the stylised gothic architecture of the late 18th century. Only the octagonal tower breaks the form, and this is not unprecedented - see Vanbrugh's Seaton Delaval.

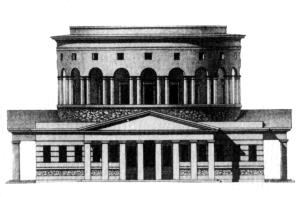

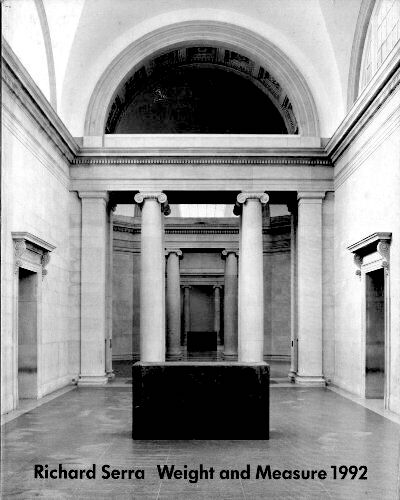

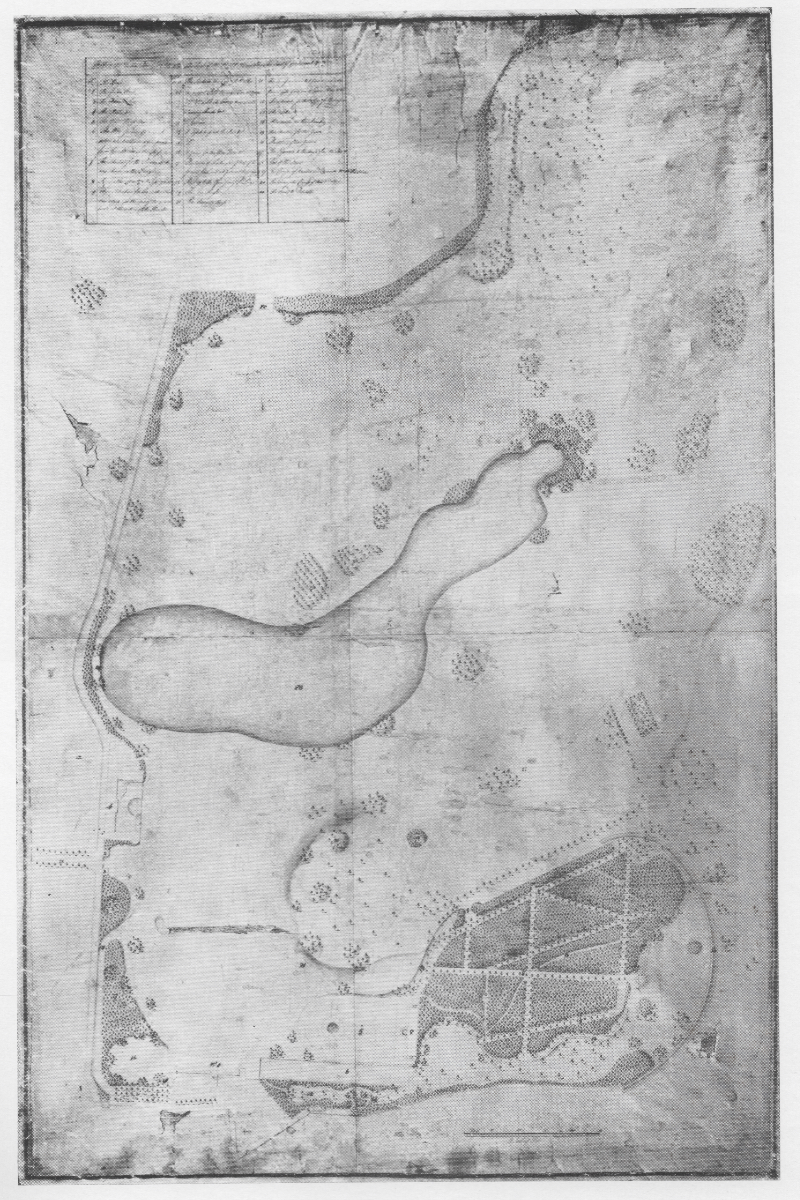

Soane office: Design for a prospect tower in the Castle style for the Earl of Egremont, 1816: Plan & elevations for Designs Nos 3 & 4

© Sir John Soane's Museum, London

© Sir John Soane's Museum, London

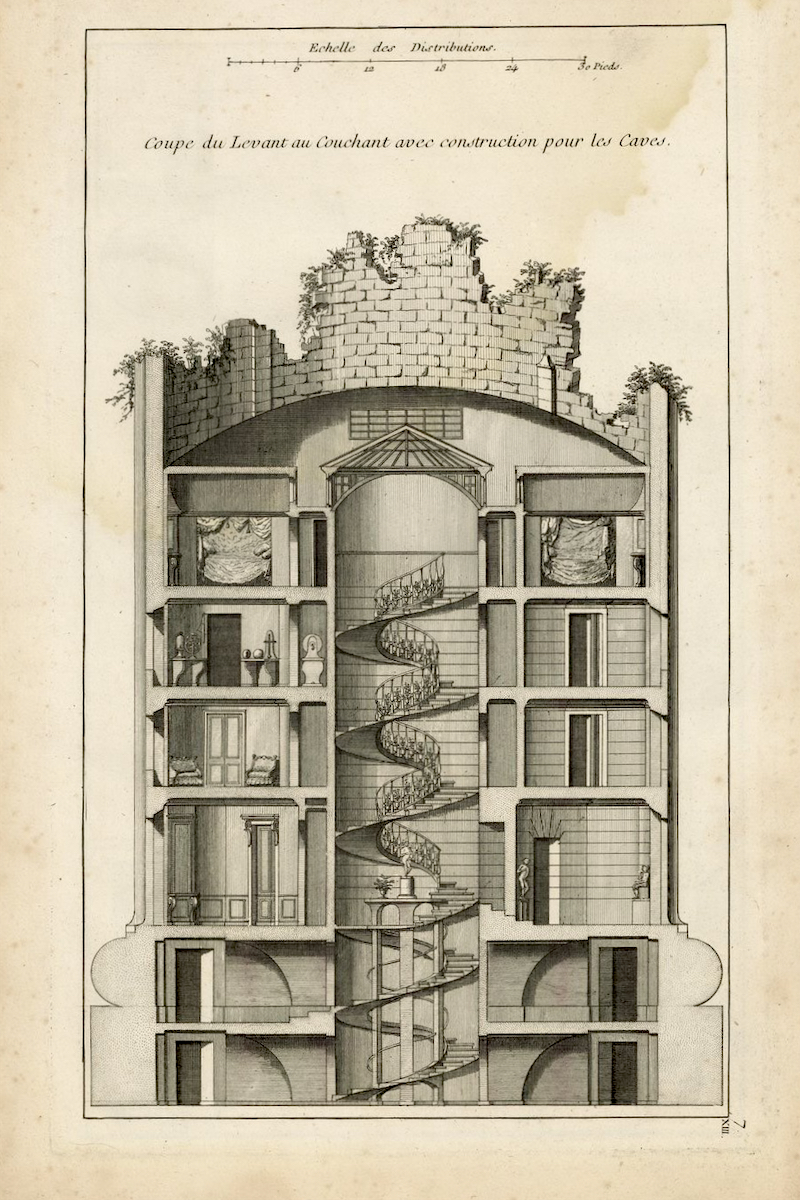

Soane's drawings were for a prospect tower, not the low dwelling in the gothic style actually built. A prospect tower was an integral part of a 'Capability' Brown landscape. Broadway Tower, Worcestershire, for example, was designed by James Wyatt in 1798 as part of 'Capability' Brown's extensive andscapes for the Earl of Coventry - his first independent commission was for the gardens at Croome nearby. Wyatt's tower is a much more accomplished building than Soane's. The interior space, and especially the staircase, make an interesting comparison to a real castle such as Elcho.

James Wyatt: Broadway Tower, Worcestershire

© Thomas Deckker 2013

© Thomas Deckker 2013

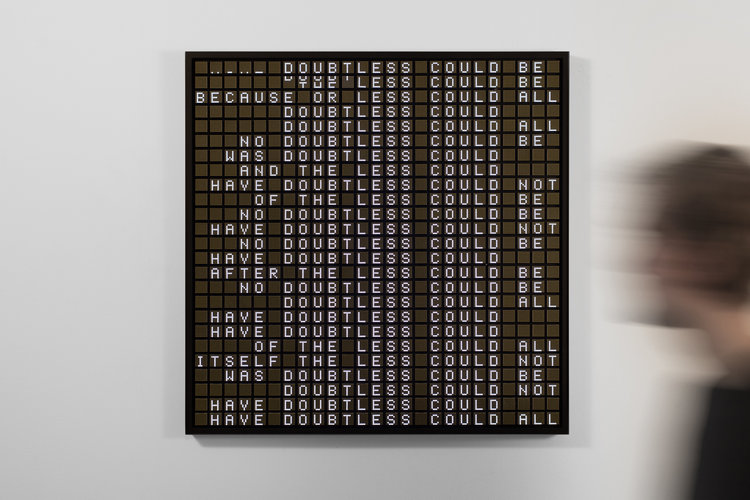

This stair is similar to Soane's unrealised design for a prospect tower and doubtless similar to the stair actually built at the Upperton Monument. The rooms are entirely contingent upon the shape of the tower, and are thus undifferentiated on each level. Nothing would be less sublime than conventional internal planning, as may be seen in later cottage ornés.

James Wyatt: Broadway Tower, Worcestershire

© Thomas Deckker 2013

James Wyatt: Broadway Tower, Worcestershire

© Thomas Deckker 2013

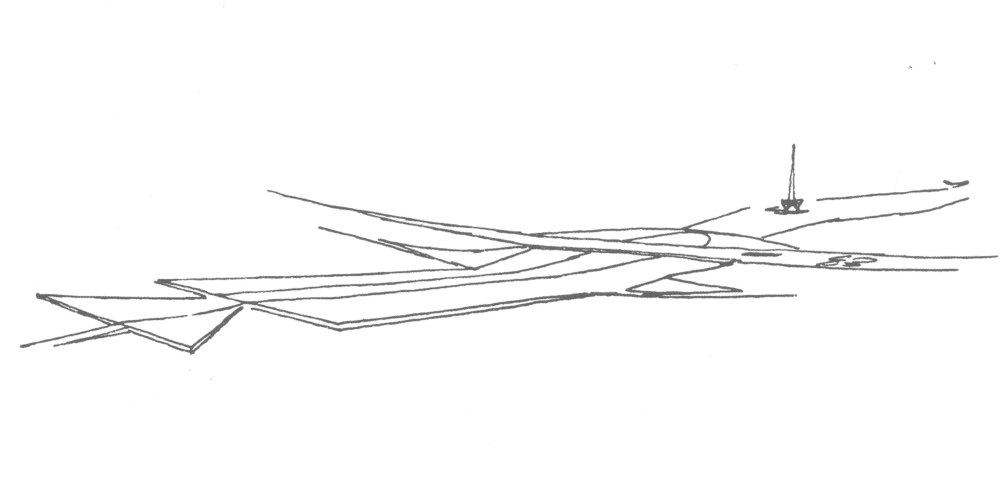

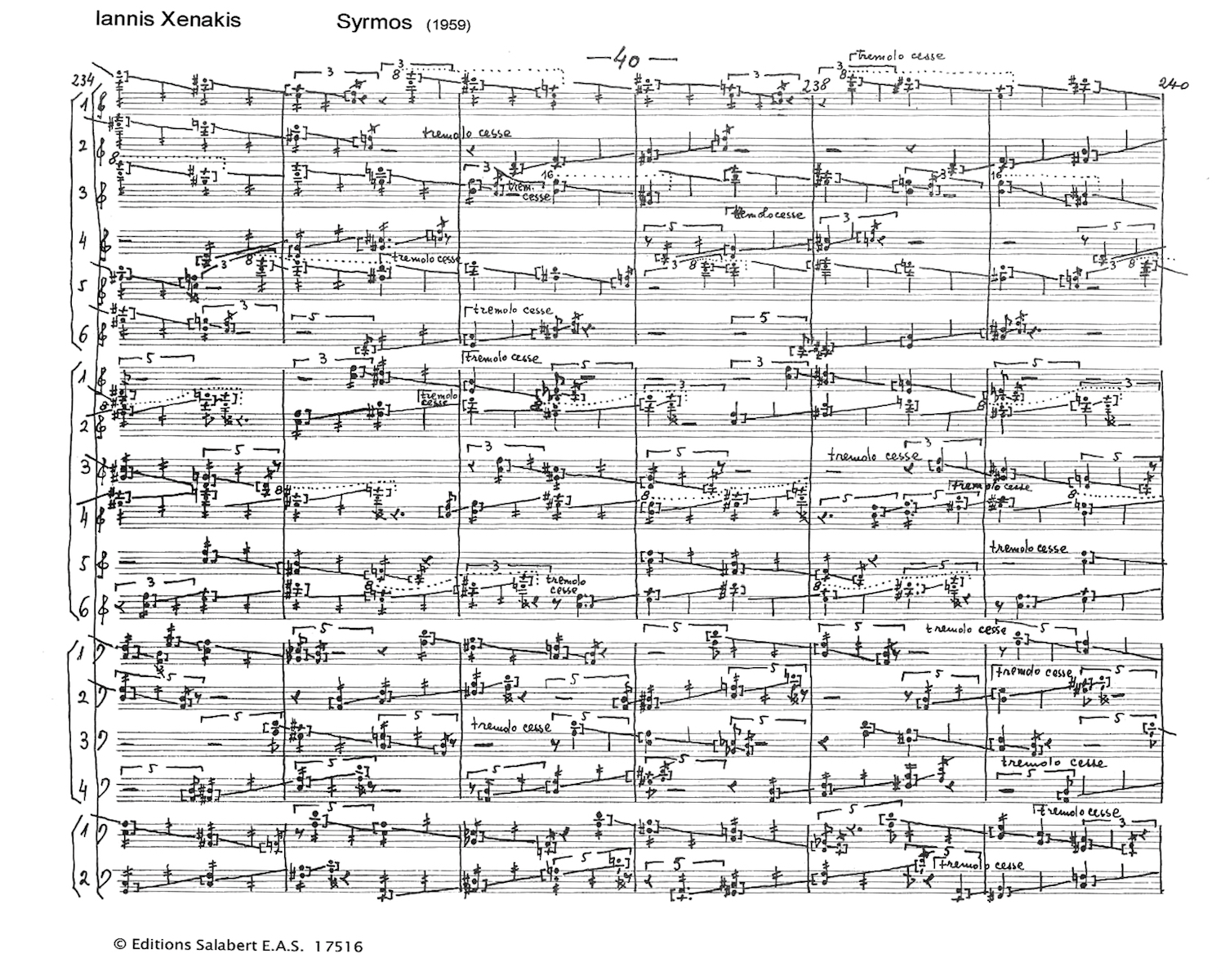

The sublime aspect, that is the contrast of the geometrical object and its naturalistic site, was clearly appreciated by the artist J. M. W. Turner in his sketchbooks of the 1820s, while a frequent visitor to Petworth. There is major collection of Turner paintings at Petworth, including some of the park which may be compared with the actual landscape through the windows. Turner's pencil sketch captures the relationship between building and landscape, doubtless the original intention of 'Capability' Brown.

Turner was one of the greatest, if not the greatest, artist of the sublime. His interest is most evident in his personal sketchbooks and watercolours, in many of which the subject is diffused in diaphanous light and colour. The concept of the sublime was put forward by Edmund Burke (1729-1801), in his Philosophical Enquiry into the Origins of Our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful (1756), only a few years after 'Capability' Brown began his career. Burke identified the aesthetic response of the sublime as more powerful and direct than pleasure, which he believed, was derived largely from 'association', conventional ideas rather than direct experience.

The Upperton Monument, Petworth Park

J. M. W Turner: Mortlake and Pulborough Sketchbook 1821-5

J. M. W Turner: Mortlake and Pulborough Sketchbook 1821-5

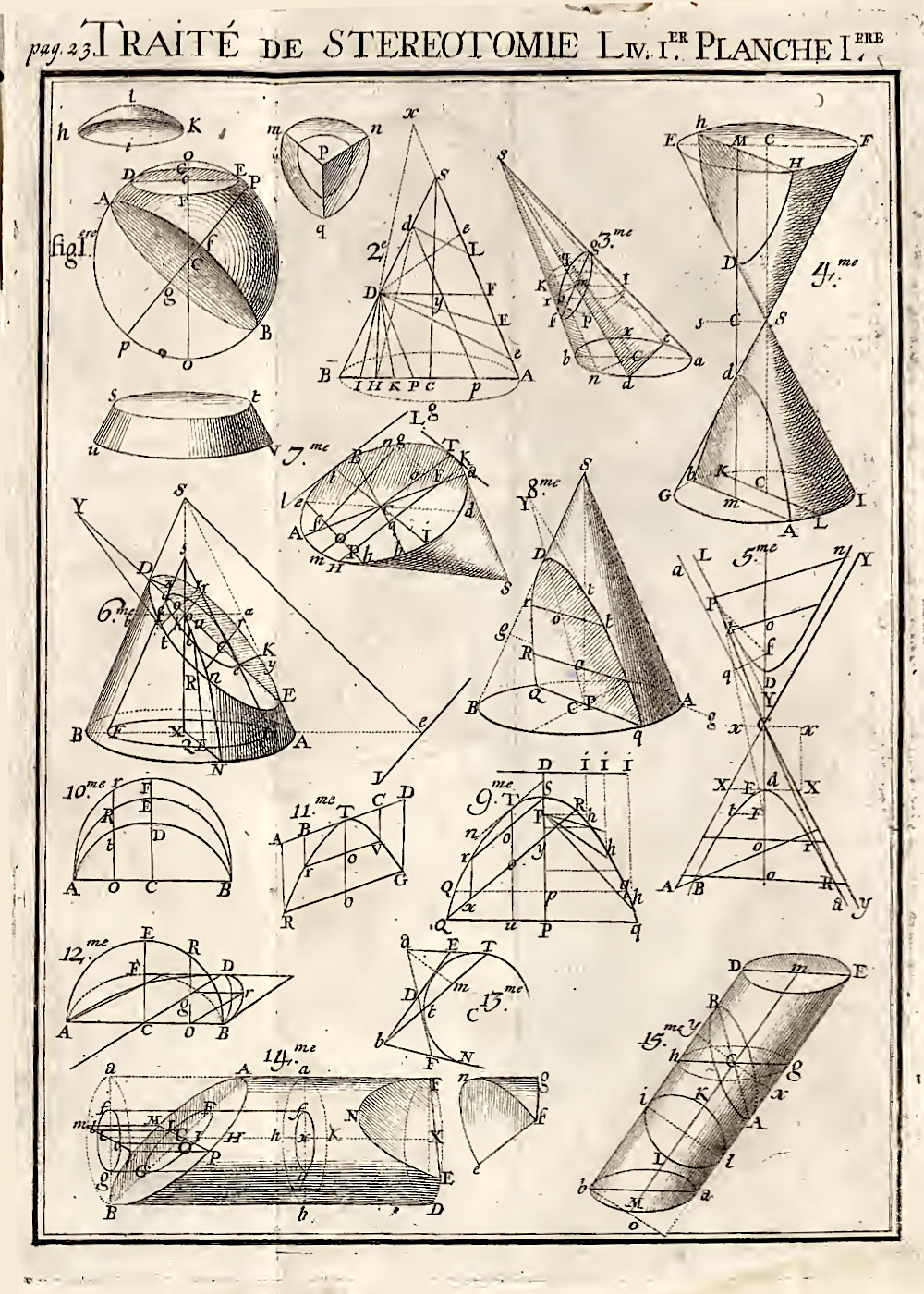

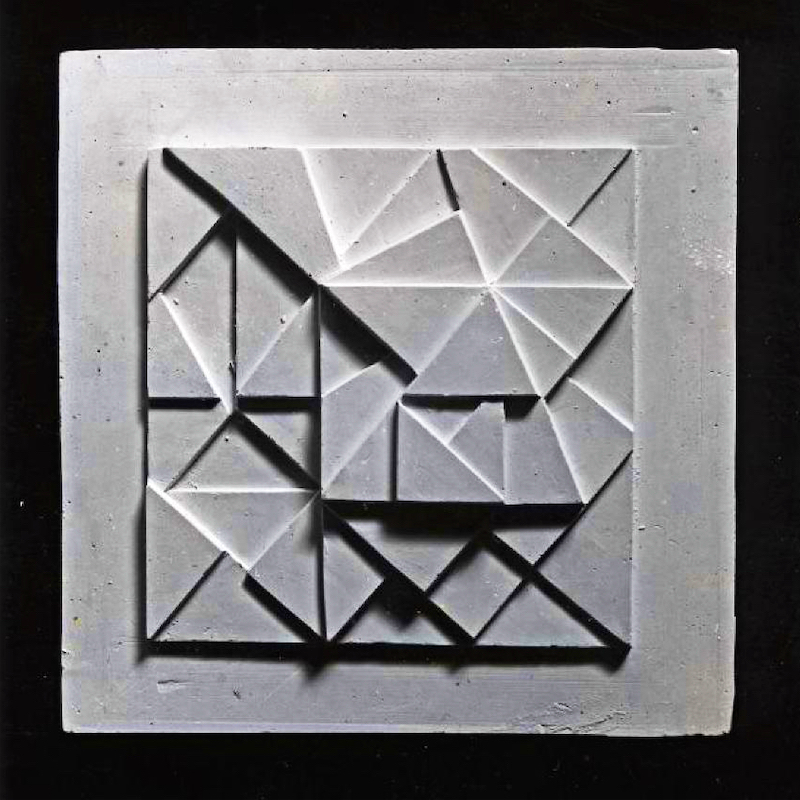

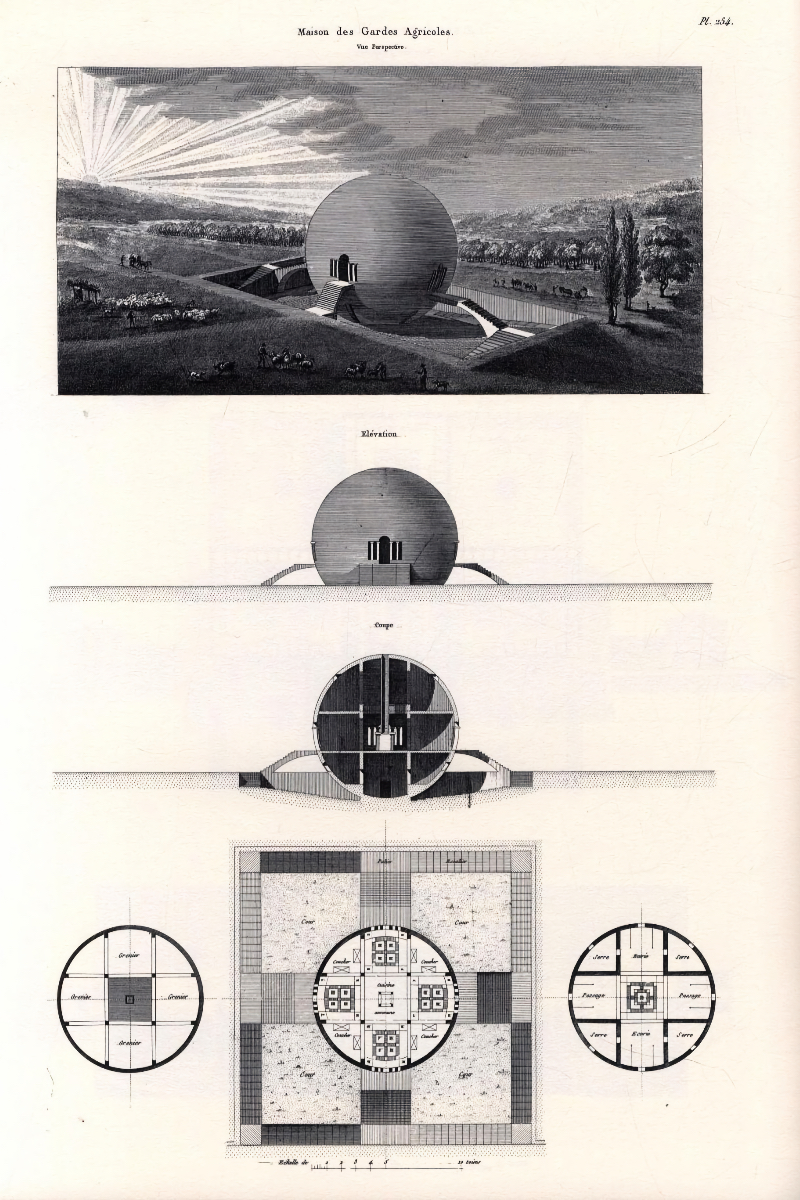

The Monument is slightly distinguished by its geometric shape: geometry is an essential aspect of the sublime, and the cubic form lifts it out of the beautiful into the sublime. The geometry of the sublime may be seen in the work of the revolutionary architect Claud-Nicolas Ledoux, whose rural buildings, projected for the ideal city of Chaux, combined the sublime with French rationality. I think it is vital for the sublime that the plan is not driven by ideas of function, but is contingent on geometry and the form of the building.

'Maison Destinée aux Surveillants de la Source de la Loue' from Claude Nicolas Ledoux: L'architecture considérée sous le rapport de l'art, des moeurs et de la législation (Paris 1804)

The architecture of the sublime

The architecture of the sublime

The cottage orné became a conventional type, as may be seen in John B. Papworth's Rural Residences, Consisting of a Series Of Designs for Cottages, Decorated Cottages, Small Villas, and other Ornamental Buildings (London 1818), and shorn of its sublime attributes. The informal planning and massing became typical of the later Gothic Revival architecture. Papworth's Rural Residences was an example of architects' pattern books, from which almost all buildings were designed by builders before the 20th century.

A Cottage Orné, designed to combine with garden scenery

The cottage orné is a new species of building in the economy of domestic architecture, and subject to its own laws of fitness and propriety. It is not the habitation of the labourer but of the affluent, of the man of study, of science, or of leisure; it is often the rallying point of domestic comfort, and in this age of elegant refinement, a mere cottage would be incongruous with the nature of its occupancy.

John B. Papworth: Rural Residences (London 1818)

The monument was quite clearly altered after construction as may be seen in the different stonework on the tower, and the difference in height between that shown in Turner's sketch and the present condition. This tower, and the presence of drainage nearby, indicate that the alterations were made to improve sanitation, and thus inhabitability, probably by Anthony Salvin who was working on Petworth House in 1869. The increased height of the tower slightly exaggerates the romantic associations, in keeping with an age accustomed to, and appreciative of, gothic architecture.

The Upperton Monument, Petworth Park

© Thomas Deckker 2021

© Thomas Deckker 2021

View from the Upperton Monument, Petworth Park

© Thomas Deckker 2021

© Thomas Deckker 2021

Thomas Deckker

London 2022

London 2022