thomas

deckker

architect

Talks at Veretec

2022-23

2022-23

BBC: The Inquiry

BBC World Service 2019

BBC World Service 2019

Brasilia: Life Beyond Utopia

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2016

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2016

Brasilia: Life Beyond Utopia

Architectural Design [April 2016]

Architectural Design [April 2016]

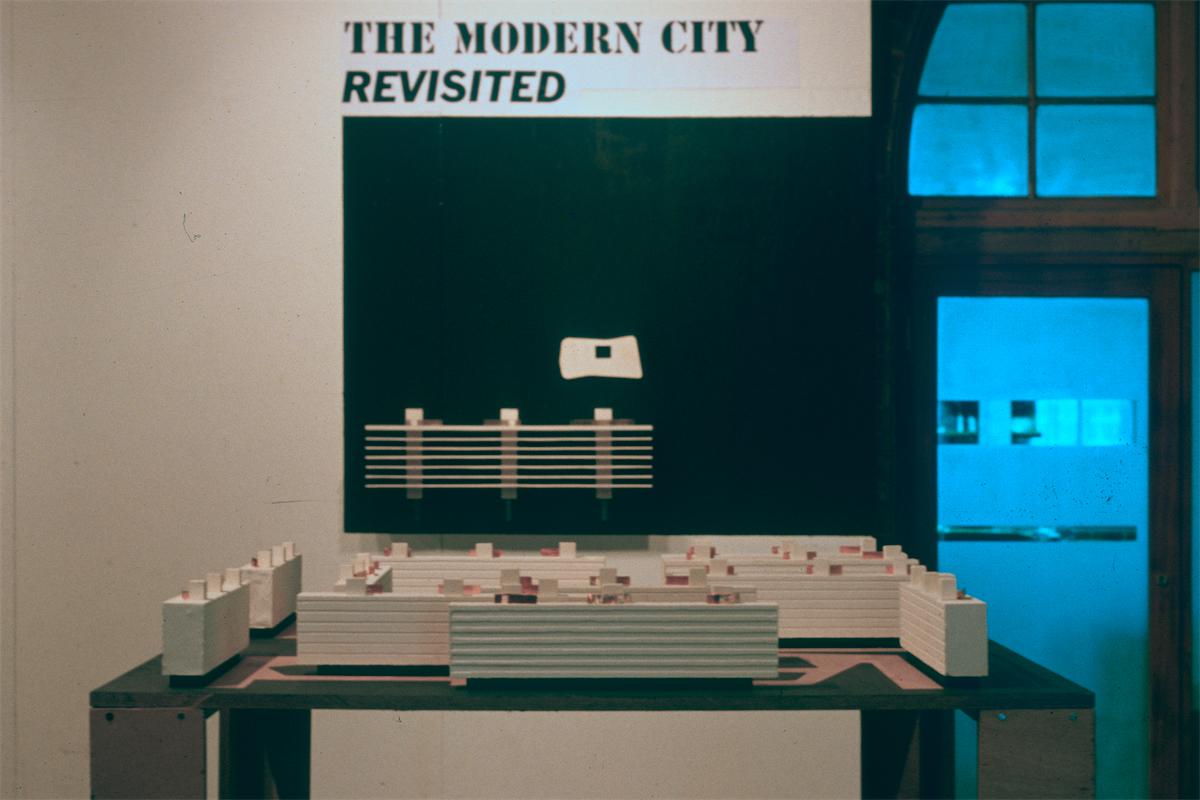

Two exhibitions for the McAslan Gallery

McAslan Gallery 2016

McAslan Gallery 2016

Edzell Castle: Architectural Treatises in Late 16th Century Scotland

Garden History Society 2014

Garden History Society 2014

Architecture and the Humanities

Architectural Research Quarterly 2014

Architectural Research Quarterly 2014

Urban Planning in Rio 1870-1930: the Construction of Modernity

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2014

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2014

Review of Remaking London: Design and Regeneration in Urban Culture

Architectural Research Quarterly 2013

Architectural Research Quarterly 2013

Life's a Beach: Oscar Niemeyer, Landscape and Women

The Rest is Noise Festival

South Bank, London 6 October 2013

The Rest is Noise Festival

South Bank, London 6 October 2013

BBC: Last Word

BBC Radio 4 7 & 9 December 2012

BBC Radio 4 7 & 9 December 2012

Brasilia: Fictions and Illusions

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2012

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2012

Connected Communities Symposium

University of Dundee 2011

University of Dundee 2011

Architecture + ESI: an architect's perspective

FESI [The UK Forum for Engineering Structural Integrity] 2011

FESI [The UK Forum for Engineering Structural Integrity] 2011

Review of Mapping London

Architectural Research Quarterly 2010

Architectural Research Quarterly 2010

The Studio of Antonio Carlos Elias

Epulis Fissuratum [Brasilia 2006]

Epulis Fissuratum [Brasilia 2006]

Urban Entropies: A Tale of Three Cities

Architectural Design [September 2003]

Architectural Design [September 2003]

New Architecture in Brazil

- Photographs by Michael Frantzis

Brazilian Embassy, London

5-6 March 2003

- Photographs by Michael Frantzis

Brazilian Embassy, London

5-6 March 2003

Natural Spirit (Places to Live 007)

Wallpaper* [January/February 2003]

Wallpaper* [January/February 2003]

Architects Directory

Wallpaper* [July/August 2002]

Wallpaper* [July/August 2002]

Foreign Legion

RIBA Journal [March 2002]

RIBA Journal [March 2002]

Architects and Technology

The Encyclopaedia of Architectural Technology [London: Wiley 2002]

The Encyclopaedia of Architectural Technology [London: Wiley 2002]

Mexican-American Architecture

Mexican-American Encyclopaedia [2002]

Mexican-American Encyclopaedia [2002]

In the Realm of the Senses

Architectural Design [July 2001]

Architectural Design [July 2001]

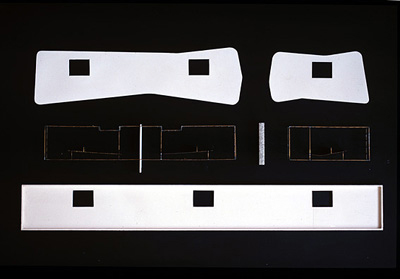

Thomas Deckker: Two Projects in Brasilia

Architectural Design [Oct 2000]

Architectural Design [Oct 2000]

First International Seminar on the Teaching of the Built Environment [SIEPAC]

University of Sao Paulo, Brazil

13-15 Sept 2000

University of Sao Paulo, Brazil

13-15 Sept 2000

vol. 6 no. 1 [University of East London 2000]

Monte Carasso: The re-invention of the site

Issues in Architecture Art & Design vol. 5 no. 2 [University of East London 1998]

Issues in Architecture Art & Design vol. 5 no. 2 [University of East London 1998]

Specific Objects / Specific Sites

Rethinking the Architecture / Landscape Relationship, University of East London,

26-28 Mar 1996

Rethinking the Architecture / Landscape Relationship, University of East London,

26-28 Mar 1996

Herzog & deMeuron

Issues in Architecture Art & Design vol. 3 no. 2 [University of East London 1994]

Issues in Architecture Art & Design vol. 3 no. 2 [University of East London 1994]

Louis Kahn: Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth

photograph © Thomas Deckker 1995

photograph © Thomas Deckker 1995

Architects and Technology Index

The Encyclopaedia of Architectural Technology [London: Wiley 2002]

Louis Kahn

Any description of the architecture of Louis Kahn (1901-1964) must start with an acknowledgement of its dual nature: simultaneously deeply rooted in the ƒcole des Beaux-Arts and Imperial Roman antiquity, and employing the most advanced techniques of structure and construction. He had studied under the Beaux-Arts trained Paul Cret at the University of Pennsylvania from 1920-24; from this he derived features of Beaux-Arts education such as marche - the rigorous analysis of spatial sequence - and disposition - combinations of forms, typically revealed through natural light. In his early private houses and wartime housing for the United States Housing Authority, however, he embodied the social and aesthetic ideals of the Modern Movement; his partner from 1942-47 was Oscar Stonorov who had edited volume 1 of Le Corbusier's Œuvre Complète (1929).

Kahn came to notice with the Yale University Art Gallery (1951-53) relatively late in his career. He specifically intended to challenge the limited spatial and material nature of International Modern architecture which was gaining ascendancy among architects (incidentally, Kahn replaced Philip Goodwin, who had designed the Museum of Modern Art, New York in 1935, as architect of the Gallery). His intention followed a study of ancient ruins while a Fellow at the American Academy in Rome in 1950, in which the brick construction of public buildings (such as his favourite Baths of Caracalla), while not their intended appearance, had become apparent. The walls of the Gallery were made of exposed brick externally and exposed block internally, with floor slabs, not of the expected smooth construction, but of what was virtually an exposed space-frame of concrete tetrahedrons. The structure was stabilised by a massive concrete cylinder containing the staircase.

Kahn acknowledged the Trenton Jewish Community Centre (1954-59) as a turning point. He started to experiment with specifically classical forms of composition; the Bathhouse, an outdoor swimming pool, was planned as a group of 5 squares, of which the central one remained void. The Unitarian Church and School, Rochester, New York (1959-69) is a mature work from this period. The protracted design period and restricted budget meant that Kahn necessarily pared form down to what he considered its essentials: massive load-bearing masonry structures with clearly-expressed lintels and concrete floor and roof slabs. This theme was further developed in the Phillips Exeter Library and Dining Hall (1965-72).

Kahn experimented with other classical forms of construction in buildings which owe some allegiance to the French architect Henri Labrouste (1801-75) or the the visionary Etienne-Louis Boullée (1728-99) - the rectilinear frame and infill panels of the Yale Centre for British Art, New Haven (1969-74), or the vaults of the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth (1966-72). These were rendered with an unprecedented attention to concrete detailing, which was also apparent in other, less classical, structures, such as the post-tensioned Vierendeel frames of the Alfred Newton Richards Medical Research Buildings, Philadelphia (1957-65) and the post-tensioned concrete beams of the project for the Palazzo dei Congressi, Venice (1968-74), or the monolithic Salk Institute for Biological Studies, San Diego (1959-65).

Kahn's attention to constructional detailing may be seen as a parallel to the stereotomy of the École des Beaux-Arts, the cutting of stone into 3-dimensional structural forms. His interest in geometry was apparent in the floor slabs of the Yale University Art Gallery, projects for tetrahedron skyscrapers for Philadelphia (1957), and the cycloidal vaults of the Kimbell Art Museum. It derived as much from Rudolf Wittkower's Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism as from recently-published books on organic geometry such as On Growth and Form by D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson, and as much from his experiences in Rome as from his friendship with Buckminster Fuller. The massive construction, layered forms, large internal volumes and small openings meant that Kahn's buildings offered excellent environmental performance. He was, of course, able to take for granted the sophisticated heating, lighting and security systems prevalent in the United States. These services were always in concealed ducts, similar to hollow masonry poché, the opposite of contemporary architectural movements, such as Brutalism, with which he otherwise had much affinity. In the Richards Buildings, services were located in closed brick towers distinct from the more open office and lab areas, while in the Salk Institute services occupied entire floors threaded through a Vierendeel structure.

The environmental and constructional approach of Kahn's architecture made his work suitable for less-developed regions without sophisticated services such as the Indian subcontinent, as may be seen in the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, India (1962-74) and Sher-e-Bangla Nagar, Dacca, Bangladesh (1962-82). Although the third choice of architect after Le Corbusier and Alvar Aalto, Kahn's buildings in Dacca are arguably the most appropriate for the climate and conditions of construction there. Double skin walls of massive brick or concrete construction acted as thermal flywheels, with the outer walls shading the inner walls and providing a gradation of light while allowing ventilation.

While Kahn has been taken as a mentor by many differing architectural factions, his most lasting legacy was to show that the classical language of architecture was profoundly rooted in experience - spatial and material.

Kahn came to notice with the Yale University Art Gallery (1951-53) relatively late in his career. He specifically intended to challenge the limited spatial and material nature of International Modern architecture which was gaining ascendancy among architects (incidentally, Kahn replaced Philip Goodwin, who had designed the Museum of Modern Art, New York in 1935, as architect of the Gallery). His intention followed a study of ancient ruins while a Fellow at the American Academy in Rome in 1950, in which the brick construction of public buildings (such as his favourite Baths of Caracalla), while not their intended appearance, had become apparent. The walls of the Gallery were made of exposed brick externally and exposed block internally, with floor slabs, not of the expected smooth construction, but of what was virtually an exposed space-frame of concrete tetrahedrons. The structure was stabilised by a massive concrete cylinder containing the staircase.

Kahn acknowledged the Trenton Jewish Community Centre (1954-59) as a turning point. He started to experiment with specifically classical forms of composition; the Bathhouse, an outdoor swimming pool, was planned as a group of 5 squares, of which the central one remained void. The Unitarian Church and School, Rochester, New York (1959-69) is a mature work from this period. The protracted design period and restricted budget meant that Kahn necessarily pared form down to what he considered its essentials: massive load-bearing masonry structures with clearly-expressed lintels and concrete floor and roof slabs. This theme was further developed in the Phillips Exeter Library and Dining Hall (1965-72).

Kahn experimented with other classical forms of construction in buildings which owe some allegiance to the French architect Henri Labrouste (1801-75) or the the visionary Etienne-Louis Boullée (1728-99) - the rectilinear frame and infill panels of the Yale Centre for British Art, New Haven (1969-74), or the vaults of the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth (1966-72). These were rendered with an unprecedented attention to concrete detailing, which was also apparent in other, less classical, structures, such as the post-tensioned Vierendeel frames of the Alfred Newton Richards Medical Research Buildings, Philadelphia (1957-65) and the post-tensioned concrete beams of the project for the Palazzo dei Congressi, Venice (1968-74), or the monolithic Salk Institute for Biological Studies, San Diego (1959-65).

Kahn's attention to constructional detailing may be seen as a parallel to the stereotomy of the École des Beaux-Arts, the cutting of stone into 3-dimensional structural forms. His interest in geometry was apparent in the floor slabs of the Yale University Art Gallery, projects for tetrahedron skyscrapers for Philadelphia (1957), and the cycloidal vaults of the Kimbell Art Museum. It derived as much from Rudolf Wittkower's Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism as from recently-published books on organic geometry such as On Growth and Form by D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson, and as much from his experiences in Rome as from his friendship with Buckminster Fuller. The massive construction, layered forms, large internal volumes and small openings meant that Kahn's buildings offered excellent environmental performance. He was, of course, able to take for granted the sophisticated heating, lighting and security systems prevalent in the United States. These services were always in concealed ducts, similar to hollow masonry poché, the opposite of contemporary architectural movements, such as Brutalism, with which he otherwise had much affinity. In the Richards Buildings, services were located in closed brick towers distinct from the more open office and lab areas, while in the Salk Institute services occupied entire floors threaded through a Vierendeel structure.

The environmental and constructional approach of Kahn's architecture made his work suitable for less-developed regions without sophisticated services such as the Indian subcontinent, as may be seen in the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, India (1962-74) and Sher-e-Bangla Nagar, Dacca, Bangladesh (1962-82). Although the third choice of architect after Le Corbusier and Alvar Aalto, Kahn's buildings in Dacca are arguably the most appropriate for the climate and conditions of construction there. Double skin walls of massive brick or concrete construction acted as thermal flywheels, with the outer walls shading the inner walls and providing a gradation of light while allowing ventilation.

While Kahn has been taken as a mentor by many differing architectural factions, his most lasting legacy was to show that the classical language of architecture was profoundly rooted in experience - spatial and material.

Thomas Deckker

London 2001

London 2001

Update August 2024

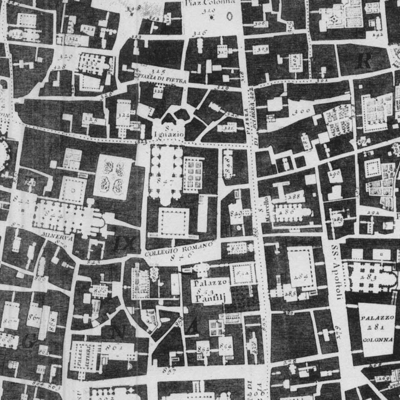

Domus Augustana, Rome

photo © Thomas Deckker 1984

photo © Thomas Deckker 1984

For some of the buildings that Louis Kahn saw on his visit to Rome in 1950, see the Domus Augustana, Rome: architecture from the high point of the Roman Empire, the brick structure stripped of all marble coverings revealing the primary components of mass and space.