Arguably the most famous Modernist roofscape is Le Corbusier's Unité d'Habitation in Marseilles. The 337 apartments, with space for up to 1,700 people, were served by an internal shopping street and a roof garden. Here one could find a children's playground and pool, a 300 metre (985 foot) long running track and a snack bar with a fashionable 'solarium'. Sculptural, rock-like shapes mirrored the distant mountains and the whole roof encapsulated Corbusier's early obsession with the ocean liner and how the summit of a vast superstructure could be utilised as a recreational area, with far-reaching views and maximum sunlight and air. Contemporary drawings compare the Unité skyline of chimneys, lift shafts, stairs and platforms with the liner's decks and funnels.

On the other side of the Atlantic, Corbusier's ideals were being realised on a much larger scale. Brasilia, planned by Oscar Niemeyer and Lucia Costa, contained dedicated residential districts in the 'wings' that sprouted from the central axis of the city plan. These districts known as 'superquadras', integrated schools, shops and recreation areas with a group of high-density housing units. The idea was to mix social classes and avoid the creation of slum housing. Some 92 'superquadras' were planned but just 10 were completed by 1964, when the new city was deemed complete. Only six of these had the original landscaping and social facilities planned by Niemeyer and the landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx.

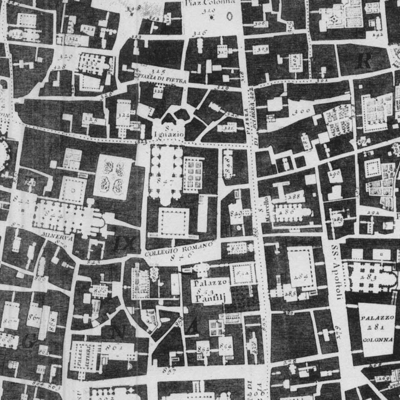

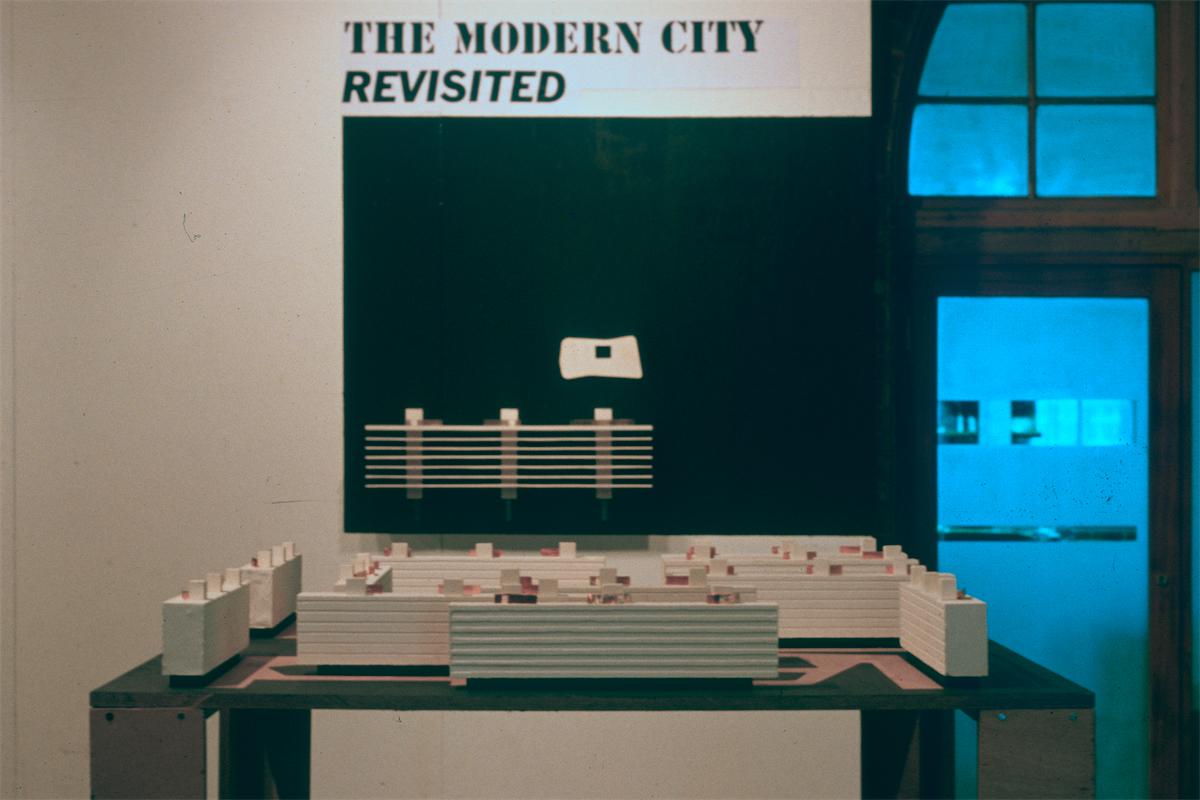

Brasilia's housing needs were demanding and went largely unmet. The architectural emphasis on social engineering pointedly omitted working-class areas and makeshift housing created for the thousands of construction workers evolved into slums. Uncompleted areas of the city plan still lie empty. The architect Thomas Deckker attempted to address some of this 'leftover' space in his Superquadras penthouse project. Noting that these vast blocks, their façades lacking the modulation and variation that characterised Corbusier's Unité, had under-utilised, 'architecturally incomplete' roof areas, Deckker set out to make the rooftops habitable.

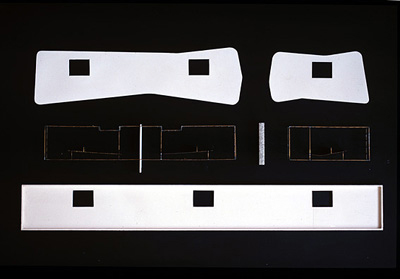

Deckker draws an unexpected comparison between the Brazilian roofscapes and the shifting sand dunes of Blakeney Point on the Norfolk coast and the way the natural erosion of the sand is artificially stabilised by a series of wooden windbreaks. The haphazard arrangement of these stakes subdivides the barren landscape into a series of architecturally distinct elements. The Superquadras presented a similarly expansive landscape, one which could also be subdivided by architectural means.

Deckker's proposal is for a series of cordons to be built on the roofs of the Superquadras, 'a wall placed against each lift tower to define "front" and "back", or "social" and "service" sides'.

Deckker is explicit about the political dimension of the unbuilt project. By creating a varied and hierarchical social mix - the new upper layer would be 'necessarily for the more sophisticated' - the Superquadras project positions the penthouse firmly as an aspirational, exclusive dwelling, almost Jn diametrical opposition to the ideals of the building's original architects.

click here to go to Wiley website with bibliographic details of Penthouse Living

thomas

deckker

architect