thomas

deckker

architect

Talks at Veretec

2022-23

2022-23

BBC: The Inquiry

BBC World Service 2019

BBC World Service 2019

Brasília: Life Beyond Utopia

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2016

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2016

Brasília: Life Beyond Utopia

Architectural Design [April 2016]

Architectural Design [April 2016]

Two exhibitions for the McAslan Gallery

McAslan Gallery 2016

McAslan Gallery 2016

Edzell Castle: Architectural Treatises in Late 16th Century Scotland

Garden History Society 2014

Garden History Society 2014

Architecture and the Humanities

Architectural Research Quarterly 2014

Architectural Research Quarterly 2014

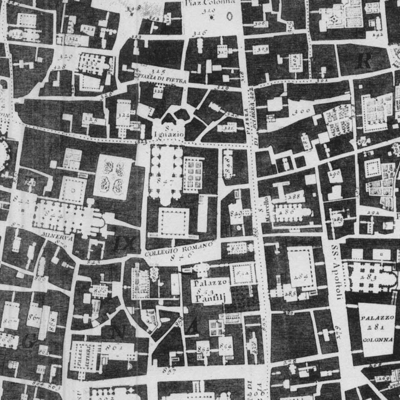

Urban Planning in Rio 1870-1930: the Construction of Modernity

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2014

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2014

Review of Remaking London: Design and Regeneration in Urban Culture

Architectural Research Quarterly 2013

Architectural Research Quarterly 2013

Life's a Beach: Oscar Niemeyer, Landscape and Women

The Rest is Noise Festival

South Bank, London 6 October 2013

The Rest is Noise Festival

South Bank, London 6 October 2013

BBC: Last Word

BBC Radio 4 7 & 9 December 2012

BBC Radio 4 7 & 9 December 2012

Brasilia: Fictions and Illusions

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2012

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2012

Connected Communities Symposium

University of Dundee 2011

University of Dundee 2011

Architecture + ESI: an architect's perspective

FESI [The UK Forum for Engineering Structural Integrity] 2011

FESI [The UK Forum for Engineering Structural Integrity] 2011

Review of Mapping London

Architectural Research Quarterly 2010

Architectural Research Quarterly 2010

The Studio of Antonio Carlos Elias

Epulis Fissuratum [Brasília 2006]

Epulis Fissuratum [Brasília 2006]

New Architecture in Brazil - Photographs by Michael Frantzis

Brazilian Embassy, London

5-6 March 2003

Brazilian Embassy, London

5-6 March 2003

Natural Spirit (Places to Live 007)

Wallpaper* [January/February 2003]

Wallpaper* [January/February 2003]

Architects Directory

Wallpaper* [July/August 2002]

Wallpaper* [July/August 2002]

Foreign Legion

RIBA Journal [March 2002]

RIBA Journal [March 2002]

Architects and Technology

The Encyclopaedia of Architectural Technology [London: Wiley 2002]

The Encyclopaedia of Architectural Technology [London: Wiley 2002]

Mexican-American Architecture

Mexican-American Encyclopaedia [2002]

Mexican-American Encyclopaedia [2002]

In the Realm of the Senses

Architectural Design [July 2001]

Architectural Design [July 2001]

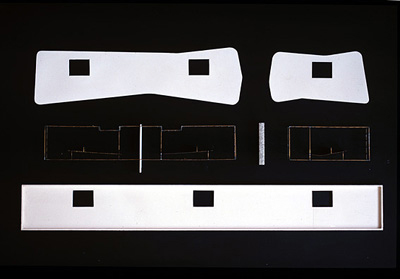

Thomas Deckker: Two Projects in Brasília

Architectural Design [Oct 2000]

Architectural Design [Oct 2000]

First International Seminar on the Teaching of the Built Environment [SIEPAC]

University of São Paulo, Brazil

13-15 Sept 2000

University of São Paulo, Brazil

13-15 Sept 2000

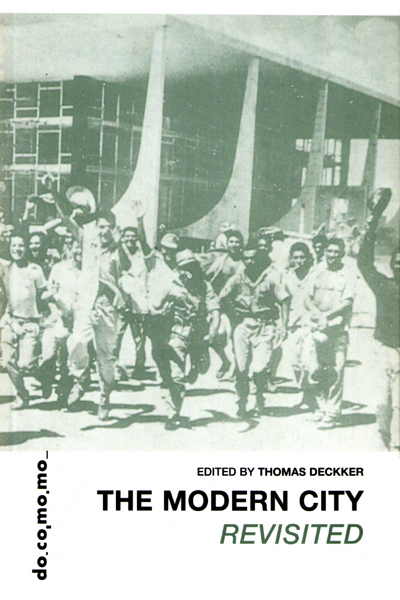

Issues in Architecture Art & Design

vol. 6 no. 1 [University of East London 2000]

vol. 6 no. 1 [University of East London 2000]

Thomas Deckker 'Land Art: City Architecture'

Monte Carasso: The re-invention of the site

Issues in Architecture Art & Design vol. 5 no. 2 [University of East London 1998]

Issues in Architecture Art & Design vol. 5 no. 2 [University of East London 1998]

Specific Objects / Specific Sites

Rethinking the Architecture / Landscape Relationship, University of East London,

26-28 Mar 1996

Rethinking the Architecture / Landscape Relationship, University of East London,

26-28 Mar 1996

Herzog & deMeuron

Issues in Architecture Art & Design vol. 3 no. 2 [University of East London 1994]

Issues in Architecture Art & Design vol. 3 no. 2 [University of East London 1994]

Mission Concepcion (1755) San Antonio, Texas

photograph © Thomas Deckker 1995

photograph © Thomas Deckker 1995

Mexican American Architecture

Mexican-American Encyclopaedia [2002]

The deserts of Northern Mexico and the South-West United States form a geographical continuum settled, from prehistoric times, by waves of nomadic and agricultural tribes. The agricultural settlements were characterised by communal dwellings in adobe construction - with thick walls and small openings - known as pueblos, in and around the fertile river valleys. The geographical isolation and the rigours of the desert environment meant that these tribes remained on the edge of the more sophisticated Meso-American cultures in the Mexican highlands; pueblos lacked the urban spaces and ceremonial centers of the Aztec and earlier Mexican cultures. Survival as agricultural communities in the desert meant that the inhabitants of the pueblos had an intimate understanding of their environment; some pueblos occupied dramatic sites for reasons of both agriculture and defence, such as Mesa Verde, Colorado (c.1000-c.1600).

Xochicalco, Mexico

photograph © Thomas Deckker 1997

photograph © Thomas Deckker 1997

After their conquest of Mexico in 1519-21, the Spanish conquistadors developed a hybrid style of architecture, mixing the native adobe construction with Spanish building types such as palaces, haciendas and monasteries in coherent urban layouts. The large landscape spaces of the New World, the necessity of imposing immediate order over the native population and the lack of an alternative political and cultural order meant that new city forms were developed quickly. Mexico City was laid out in a grid pattern in 1521 which established the pattern for urban development in the Spanish New World. These cities were intended to represent the social hierarchy of the colony, and were centered on large public squares with the main church and palace, with the houses of the poorer inhabitants forming an anonymous background. Despite the European appearance of the cities, some similarity in character remained between the new urban spaces, such as the sixteenth-century Zocalo in Mexico City, and those of Meso-American architecture, such as the sixth-century Citadel at Teotihuacan (not least because Mexico City was built on the ruins of Tenochtitlan), which made Mexican architecture distinct.

Outside of the urban centers the settlement of the native populations was undertaken by religious orders in Missions. Missions comprised churches, ceremonial spaces and huts for the native populations. The Spanish were barely able to colonize the vast expanse of Northern Mexico and the South-West, however, and were not able to suppress the pueblos entirely as they intended. Perhaps the most famous of the Missions is the Alamo in San Antonio, Texas, the scene of a famous siege in the wars between the Mexico and the United States in 1845.

Spanish America fell to the United States after a series of wars aimed primarily at territorial expansion which ended in 1848 with the Peace of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, which made the Rio Grande the main part of the border; the geographical isolation and the unsuitability of the desert for conventional agriculture meant, again, that the South-West was mainly bypassed. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries Mexico and the United States developed in radically opposed directions. While Mexico remained agricultural, the United States had become, by the end of World War I, the world's foremost industrial power.

The border created new towns and a new mythology about Mexico in the United States. Tijuana and Nuevo Laredo were founded in 1848; Nogales in 1882, and Mexicali in 1903. As local government and businesses in the United States began to exert more control over the zoning and development of cities, and in 1920 the Federal government prohibited the sale of alcohol, so these border towns began to develop zonas de tolerancia of bars and brothels; a popular mythology sprang up that the border epitomised the whole of Mexico. As the United States was by far the richer partner there was little the Mexico could do to control or counter it.

The colonisation of the new 'West' by settlers from the eastern United States was facilitated by houses built from 'balloon frame' construction. The 'balloon frame' used closely-spaced timber studs (in the walls) and joists (in the floors and roofs) clad in timber boards; it relied on a sophisticated system of sawmills, transportation and labor. Architecturally, it was suited to individual houses with little contact between inside and outside. This form of construction thus had little suitability to the materials available or the climate of the desert regions, but it became widespread in the new border region.

Due to the peculiar social and architectural forms of the pueblos a direct relationship to contemporary practice was, in reality, rarely possible. The pueblos of the South-West, both ruined and inhabited, like the Meso-American ruins of Mexico, were discovered through the work of ethnographers and archeologists rather than architects as the ruins of Ancient Greece and Rome had been. One exception was the winter house of the architect Frank Lloyd Wright (1869-1959) in Scottsdale, Arizona, known as Taliesin West (1938). In its original form with canvas roofs over heavy stone walls it must have been like camping out in a pueblo ruin. Wright also built some distinctly 'Mayan' houses in California such as the Hollyhock House, Los Angeles (1916). The 'Mission' style gained widespread popular acceptance throughout former Spanish America, although this style was, as was common in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, decorative with a distant relationship to the real buildings of Spanish America.

It was not until the Revolution in 1911 that Mexico began to pursue a policy of national self-sufficiency in all areas of life. The arrival of European Modern architecture - of white concrete walls and dramatic cubic shapes, popularised by the Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier (1888-1965) - in the 1920s acted as a catalyst for architects breaking away from the eclectic styles of the nineteenth century in both Mexico and the United States. In fact very few buildings in the European Modern style were built in either Mexico or the United States; this style was too restricted, constructionally, environmentally and aesthetically, to be relevant. One remarkable pair of buildings in this style were the houses built for the artists Diego Rivera (1886-1957) and Frida Kahlo (1907-54) in San Angel, a suburb of Mexico City, by the architect Juan O'Gorman (1905-82) in 1931.

During the 1930s Mexico City became a haven for artists of all kinds escaping temporarily - and sometimes permanently - from the culturally and politically conservative United States. While the Meso-American ruins were an obvious draw for architects, they also appreciated the vivid urban life in Mexico City at a time when cities in the United States were beginning to fragment into suburbs. The active involvement of the state in commissioning architecture was seen by many as a practical example to President Roosevelt's New Deal. Mexican architecture began to be known world wide in publications such as The New Architecture in Mexico (1937) by Esther Born, Modern Architecture in Mexico (1961) by Max L Cetto and Builders in the Sun: Five Mexican Architects (New York 1967) by Clive Bamford Smith.

Most of the buildings shown in these books were in the International Style, the austere and highly technological world-wide development of the European Modern style which seemed to underwrite Mexico as an architectural equal among the world's nations. The different levels of industrialisation meant that steel was a more economical building material in the United States and concrete in Mexico: structural steel required sophisticated rolling mills and skilled labor in site, while concrete needed only simple steel reinforcing bars and unskilled labor on site. This gave Mexican architecture in general an improvised quality distinct from the precision of buildings in the United States. On the other hand concrete, due to its plasticity, could be a poetic material and many concrete engineers came to prominence, such as Felix Candela (1910-97).

It was not until the late 1930s that one exceptional Mexican architect came to be recognized: Luis Barragan (1902-88). Barragan has started building in the European Modern style in Mexico City in the 1920s but had moved on to create a personal manner which married the artistic sophistication of European architecture with forms derived from Spanish-American architecture. It transcended its deliberately primitive construction with spaces of poetry and memory. Barragan had grown up in the state of Guadalajara, in northern Mexico, and Barragan referred constantly to haciendas and convents. Barragan practiced as a town-planner - at the suburb of El Pedragal (1945-5), architect - such as his own house in the suburb of Tacubaya (1947-48), and garden designer.

Outside of the urban centers the settlement of the native populations was undertaken by religious orders in Missions. Missions comprised churches, ceremonial spaces and huts for the native populations. The Spanish were barely able to colonize the vast expanse of Northern Mexico and the South-West, however, and were not able to suppress the pueblos entirely as they intended. Perhaps the most famous of the Missions is the Alamo in San Antonio, Texas, the scene of a famous siege in the wars between the Mexico and the United States in 1845.

Spanish America fell to the United States after a series of wars aimed primarily at territorial expansion which ended in 1848 with the Peace of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, which made the Rio Grande the main part of the border; the geographical isolation and the unsuitability of the desert for conventional agriculture meant, again, that the South-West was mainly bypassed. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries Mexico and the United States developed in radically opposed directions. While Mexico remained agricultural, the United States had become, by the end of World War I, the world's foremost industrial power.

The border created new towns and a new mythology about Mexico in the United States. Tijuana and Nuevo Laredo were founded in 1848; Nogales in 1882, and Mexicali in 1903. As local government and businesses in the United States began to exert more control over the zoning and development of cities, and in 1920 the Federal government prohibited the sale of alcohol, so these border towns began to develop zonas de tolerancia of bars and brothels; a popular mythology sprang up that the border epitomised the whole of Mexico. As the United States was by far the richer partner there was little the Mexico could do to control or counter it.

The colonisation of the new 'West' by settlers from the eastern United States was facilitated by houses built from 'balloon frame' construction. The 'balloon frame' used closely-spaced timber studs (in the walls) and joists (in the floors and roofs) clad in timber boards; it relied on a sophisticated system of sawmills, transportation and labor. Architecturally, it was suited to individual houses with little contact between inside and outside. This form of construction thus had little suitability to the materials available or the climate of the desert regions, but it became widespread in the new border region.

Due to the peculiar social and architectural forms of the pueblos a direct relationship to contemporary practice was, in reality, rarely possible. The pueblos of the South-West, both ruined and inhabited, like the Meso-American ruins of Mexico, were discovered through the work of ethnographers and archeologists rather than architects as the ruins of Ancient Greece and Rome had been. One exception was the winter house of the architect Frank Lloyd Wright (1869-1959) in Scottsdale, Arizona, known as Taliesin West (1938). In its original form with canvas roofs over heavy stone walls it must have been like camping out in a pueblo ruin. Wright also built some distinctly 'Mayan' houses in California such as the Hollyhock House, Los Angeles (1916). The 'Mission' style gained widespread popular acceptance throughout former Spanish America, although this style was, as was common in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, decorative with a distant relationship to the real buildings of Spanish America.

It was not until the Revolution in 1911 that Mexico began to pursue a policy of national self-sufficiency in all areas of life. The arrival of European Modern architecture - of white concrete walls and dramatic cubic shapes, popularised by the Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier (1888-1965) - in the 1920s acted as a catalyst for architects breaking away from the eclectic styles of the nineteenth century in both Mexico and the United States. In fact very few buildings in the European Modern style were built in either Mexico or the United States; this style was too restricted, constructionally, environmentally and aesthetically, to be relevant. One remarkable pair of buildings in this style were the houses built for the artists Diego Rivera (1886-1957) and Frida Kahlo (1907-54) in San Angel, a suburb of Mexico City, by the architect Juan O'Gorman (1905-82) in 1931.

During the 1930s Mexico City became a haven for artists of all kinds escaping temporarily - and sometimes permanently - from the culturally and politically conservative United States. While the Meso-American ruins were an obvious draw for architects, they also appreciated the vivid urban life in Mexico City at a time when cities in the United States were beginning to fragment into suburbs. The active involvement of the state in commissioning architecture was seen by many as a practical example to President Roosevelt's New Deal. Mexican architecture began to be known world wide in publications such as The New Architecture in Mexico (1937) by Esther Born, Modern Architecture in Mexico (1961) by Max L Cetto and Builders in the Sun: Five Mexican Architects (New York 1967) by Clive Bamford Smith.

Most of the buildings shown in these books were in the International Style, the austere and highly technological world-wide development of the European Modern style which seemed to underwrite Mexico as an architectural equal among the world's nations. The different levels of industrialisation meant that steel was a more economical building material in the United States and concrete in Mexico: structural steel required sophisticated rolling mills and skilled labor in site, while concrete needed only simple steel reinforcing bars and unskilled labor on site. This gave Mexican architecture in general an improvised quality distinct from the precision of buildings in the United States. On the other hand concrete, due to its plasticity, could be a poetic material and many concrete engineers came to prominence, such as Felix Candela (1910-97).

It was not until the late 1930s that one exceptional Mexican architect came to be recognized: Luis Barragan (1902-88). Barragan has started building in the European Modern style in Mexico City in the 1920s but had moved on to create a personal manner which married the artistic sophistication of European architecture with forms derived from Spanish-American architecture. It transcended its deliberately primitive construction with spaces of poetry and memory. Barragan had grown up in the state of Guadalajara, in northern Mexico, and Barragan referred constantly to haciendas and convents. Barragan practiced as a town-planner - at the suburb of El Pedragal (1945-5), architect - such as his own house in the suburb of Tacubaya (1947-48), and garden designer.

Luis Barragan: Las Arboledas, Mexico City

photograph © Thomas Deckker 1997

photograph © Thomas Deckker 1997

While Barragan was not considered 'Modern' at the time because he did not promote the primacy of technology in architecture, he was appreciated by architects trying to free themselves equally from European Modernism and standard American domestic architecture. This was particularly true of California in the 1940s and 1950s. California Arts and Architecture, for example, one of the most highly-regarded magazines of the time, published Barragan's work alongside that of the architect Richard Neutra (1892-1970) who was also distancing himself from his European Modern roots in search of a manner more suited to the California life-style and environment. The Kaufmann House, Palm Springs (1946) characterised his mature work; it had masonry walls which extended the plan into the landscape and a very light steel-framed structure with extensive opening windows protected by roof overhangs. Barragan's work became more widely appreciated as technology assumed a less predominant position in architecture and the International Style faded in the 1970s; he was awarded the Pritzker Prize, the foremost award for architecture in the United States, in 1980.

When the American architect Louis Kahn (1901-1974) was building the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, San Diego (1959-65), regarded as one of the greatest recent buildings in the United States, he decided to seek Barragan's opinion on what to build in the central courtyard space, and so flew Barragan from Mexico City to the building site (he had just visited Barragan's house in Mexico City). Surveying the sea of mud, Barragan told him to leave it empty, and the space became a paved plaza crossed only by a small stream of water - a space of contemplation derived from Barragan's memories of haciendas in his native state of Guadalajara and, ultimately, from Meso-American monuments.

This sophisticated discussion between two world-famous architects was very different from the usual experience of Mexicans in the United States. Their conversation took place just north of most disputed part of the border - the Tijuana/San Diego steel fence designed to stop illegal Mexican immigration into the United States. Enormous numbers of Mexicans live and work - legally and illegally - in the border region of the United States; their main motive is benefit from its industrial economy. The areas where these migrants live - such as the barrios of East Los Angeles - resemble the more densely urban forms of Mexican cities, although their economic and physical deprivation is in contrast to their richer neighbours.

The border region has begun to develop a distinct architectural culture, however. The Mexican architect Ricardo Leggoretta (1931-2011) popularised and extended Barragan's manner and has worked extensively in Mexico and the United States; there is little to distinguish in quality between the Monterrey Central Library, Mexico (1994) and the San Antonio Public Library, Texas (1995). Leggoretta, like Barragan, combines sophisticated spaces with features derived from Spanish American architecture such as courtyards, fountains and long shady corridors. Antoine Predock (1936-) also makes buildings with heavy construction and shading devices responsive to the desert environment centered on dramatic public spaces but without any specifically historical features, such as the Nelson Fine Arts Buildings, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona (1985-89).

One of the most moving works of architecture in the border region was created by the New York City artist Donald Judd (1928-94) at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas. Judd, looking for a place to exhibit his work, bought a disused army barracks (used to patrol the border in the 1930s) in 1972 and renovated the buildings. Judd was an admirer of Barragan and felt a strong affinity to Mexican culture. He employed many Mexican workers in his architectural enterprises and used native forms of construction, not least as a protest against the exploitation and destruction of the environment by industrial concerns and suburban houses. His work, long lines of concrete boxes in the desert or aluminum boxes displayed in the former airplane hangars, has the same spiritual quality as the pueblo artefacts and is a happier alternative to the steel fence.

When the American architect Louis Kahn (1901-1974) was building the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, San Diego (1959-65), regarded as one of the greatest recent buildings in the United States, he decided to seek Barragan's opinion on what to build in the central courtyard space, and so flew Barragan from Mexico City to the building site (he had just visited Barragan's house in Mexico City). Surveying the sea of mud, Barragan told him to leave it empty, and the space became a paved plaza crossed only by a small stream of water - a space of contemplation derived from Barragan's memories of haciendas in his native state of Guadalajara and, ultimately, from Meso-American monuments.

This sophisticated discussion between two world-famous architects was very different from the usual experience of Mexicans in the United States. Their conversation took place just north of most disputed part of the border - the Tijuana/San Diego steel fence designed to stop illegal Mexican immigration into the United States. Enormous numbers of Mexicans live and work - legally and illegally - in the border region of the United States; their main motive is benefit from its industrial economy. The areas where these migrants live - such as the barrios of East Los Angeles - resemble the more densely urban forms of Mexican cities, although their economic and physical deprivation is in contrast to their richer neighbours.

The border region has begun to develop a distinct architectural culture, however. The Mexican architect Ricardo Leggoretta (1931-2011) popularised and extended Barragan's manner and has worked extensively in Mexico and the United States; there is little to distinguish in quality between the Monterrey Central Library, Mexico (1994) and the San Antonio Public Library, Texas (1995). Leggoretta, like Barragan, combines sophisticated spaces with features derived from Spanish American architecture such as courtyards, fountains and long shady corridors. Antoine Predock (1936-) also makes buildings with heavy construction and shading devices responsive to the desert environment centered on dramatic public spaces but without any specifically historical features, such as the Nelson Fine Arts Buildings, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona (1985-89).

One of the most moving works of architecture in the border region was created by the New York City artist Donald Judd (1928-94) at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas. Judd, looking for a place to exhibit his work, bought a disused army barracks (used to patrol the border in the 1930s) in 1972 and renovated the buildings. Judd was an admirer of Barragan and felt a strong affinity to Mexican culture. He employed many Mexican workers in his architectural enterprises and used native forms of construction, not least as a protest against the exploitation and destruction of the environment by industrial concerns and suburban houses. His work, long lines of concrete boxes in the desert or aluminum boxes displayed in the former airplane hangars, has the same spiritual quality as the pueblo artefacts and is a happier alternative to the steel fence.

Luis Barragan: El Muro Rojo, Mexico City

photograph © Thomas Deckker 1997

photograph © Thomas Deckker 1997