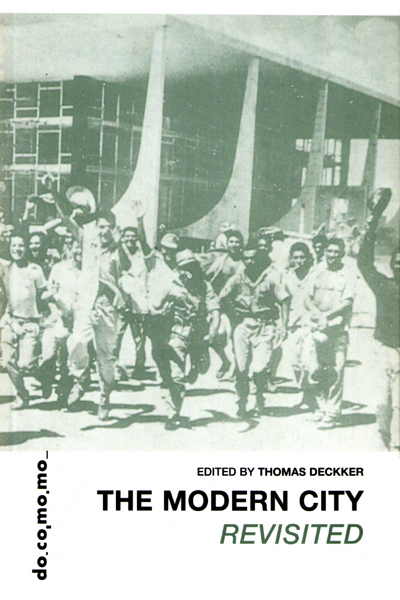

Architecture in São Paulo never adhered to the 'Brazilian Style', the Brazilian appropriation of European Modernism of Lucio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer in Rio de Janeiro so strongly identified with Getúio Vargas, with the Estado Novo, and with Juscelino Kubitschek. If it did not share in the glory of its international success in the 1940s and 1950s, neither did it share in its total collapse in the 1960s. On the contrary, the demise of the International Style and the insurrection of Team X in Europe - Aldo van Eyck, Giancarlo de Carlo, Alison & Peter Smithson, Jakob Bakema - found full correspondence with the main practitioners in São Paulo - Lina Bo Bardi (1914-92), architect of the Museum of Art of São Paulo (1957-68) and the SESC-Pompéia [Pompéia Cultural Centre] (1977) and João Vilanova Artigas (1915-1985), architect and Professor of the Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade de São Paulo [Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism of the University of São Paulo] (1961). Their emphasis on 'place' not 'space' led to a reconciliation with the urban fabric to which the International Style was ideologically and aesthetically opposed.

Since the beginning of the 20th century the population of São Paulo has grown from 200,000 to 16,000,000. It has become an orthodoxy in planning studies that the resulting problems are intractable and insoluble. The separate physical spaces of the upper and lower classes, in particular, is felt to reflect their different political spaces. Such attitudes have been thrown into doubt by the success of architecture in providing a conduit for urban regeneration, from the Centre Pompidou in Paris in 1978 to the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao in 2001. While Brazil was late in confronting the issues raised by the massive increase in urban population, mainly due to the military dictatorship from 1964 to 1984, there has been, since the return to democracy, an increasing drive to catch up.

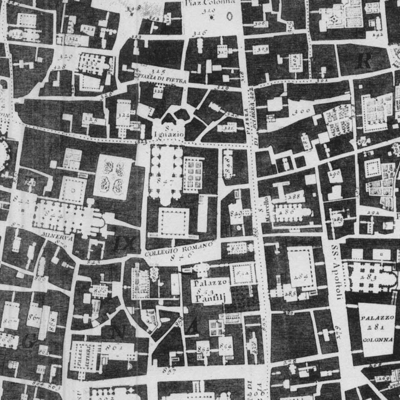

The critical test of urban regeneration is, of course, to provide any necessary improvements without suffocating the vitality and variety of urban life. The area of the centre of São Paulo from Anhangabaú to the Estação da Luz, the

bairro de Santa Ifigênia, is one of the most complex and heterogeneous in the city, a mixture of historical buildings, offices, middle class apartments and

cortiços [urban slums] at phenomenal densities. The recovery of a group of buildings there - the Teatro Municipal, the Estação da Luz, the Estação Julio Prestes and the Pinacoteca do Estado, to name only the most prominent - is more than just a re-establishment of architecture: it is a recovery of historical and political space.

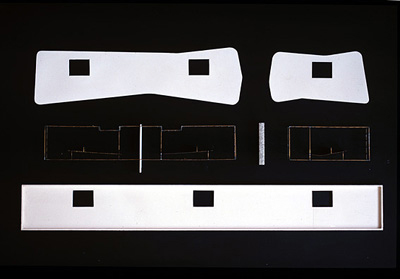

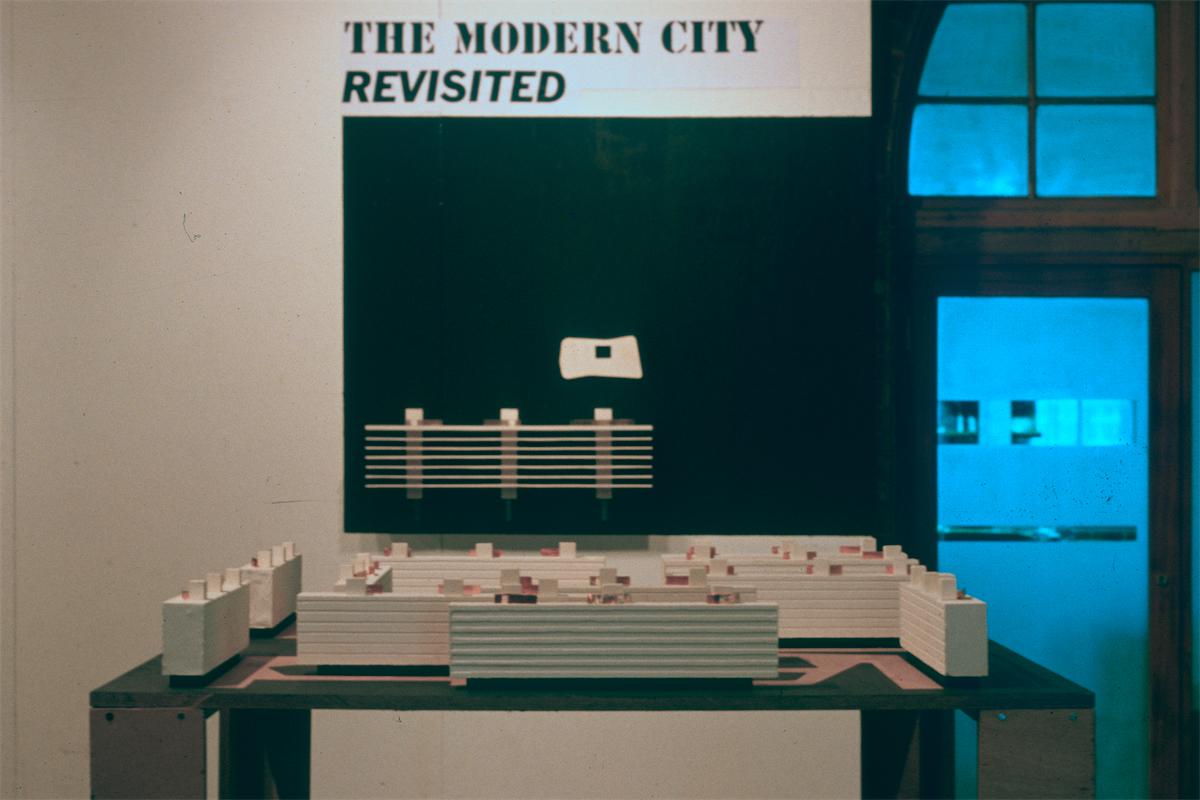

While the work of the outstanding architects of the post-war period - Bardi in particular - has become quite well known outside Brazil, the work of the later generations is so little known that it is a common assumption that there is currently a total vacuum in architectural production in Brazil. It is interesting to trace the work of one architect, Joaquim Guedes (b. 1932), from the 1970s, with his preoccupation with Team X and the later work of Le Corbusier and Alvar Aalto, to his most recent work rooted in the abstractions of site and the reticence of form strongly identified with 'critical regionalism' but, more rewardingly, with the specifics of place and light. Much of his work is in the Jardims [Gardens] originally laid out by the English Garden City architects Barry Parker & Raymond Unwin but now, with much alteration and expansion, the prime residential district of the centre of São Paulo. My own rather surprising commission for the

Magalhæs House in Brasília was an attempt to redress the dismal void in architecture there since the original plan of Lucio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer from 1957 to 1960.

These photographs by Michael Frantzis ask us to look at recent work in Brazil not only as serious architectural objects but as ones rooted in their urban context. The intensity of his vision and the technical perfection of their execution begs us to consider these works as fully the equal of any in Europe.