thomas

deckker

architect

Talks at Veretec

2022-23

2022-23

BBC: The Inquiry

BBC World Service 2019

BBC World Service 2019

Brasília: Life Beyond Utopia

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2016

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2016

Brasília: Life Beyond Utopia

Architectural Design [April 2016]

Architectural Design [April 2016]

Two exhibitions for the McAslan Gallery

McAslan Gallery 2016

McAslan Gallery 2016

Edzell Castle: Architectural Treatises in Late 16th Century Scotland

Garden History Society 2014

Garden History Society 2014

Architecture and the Humanities

Architectural Research Quarterly 2014

Architectural Research Quarterly 2014

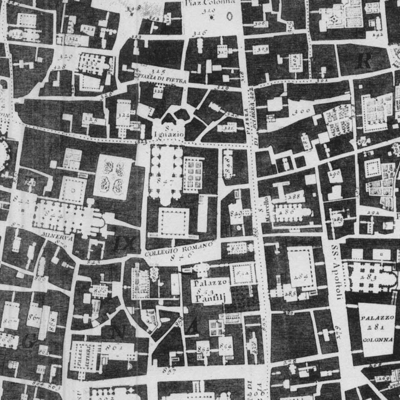

Urban Planning in Rio 1870-1930: the Construction of Modernity

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2014

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2014

Review of Remaking London: Design and Regeneration in Urban Culture

Architectural Research Quarterly 2013

Architectural Research Quarterly 2013

Life's a Beach: Oscar Niemeyer, Landscape and Women

The Rest is Noise Festival

South Bank, London 6 October 2013

The Rest is Noise Festival

South Bank, London 6 October 2013

BBC: Last Word

BBC Radio 4 7 & 9 December 2012

BBC Radio 4 7 & 9 December 2012

Brasilia: Fictions and Illusions

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2012

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2012

Connected Communities Symposium

University of Dundee 2011

University of Dundee 2011

Architecture + ESI: an architect's perspective

FESI [The UK Forum for Engineering Structural Integrity] 2011

FESI [The UK Forum for Engineering Structural Integrity] 2011

Review of Mapping London

Architectural Research Quarterly 2010

Architectural Research Quarterly 2010

The Studio of Antonio Carlos Elias

Epulis Fissuratum [Brasília 2006]

Epulis Fissuratum [Brasília 2006]

New Architecture in Brazil - Photographs by Michael Frantzis

Brazilian Embassy, London

5-6 March 2003

Brazilian Embassy, London

5-6 March 2003

Natural Spirit (Places to Live 007)

Wallpaper* [January/February 2003]

Wallpaper* [January/February 2003]

Architects Directory

Wallpaper* [July/August 2002]

Wallpaper* [July/August 2002]

Foreign Legion

RIBA Journal [March 2002]

RIBA Journal [March 2002]

Architects and Technology

The Encyclopaedia of Architectural Technology [London: Wiley 2002]

The Encyclopaedia of Architectural Technology [London: Wiley 2002]

Mexican-American Architecture

Mexican-American Encyclopaedia [2002]

Mexican-American Encyclopaedia [2002]

In the Realm of the Senses

Architectural Design [July 2001]

Architectural Design [July 2001]

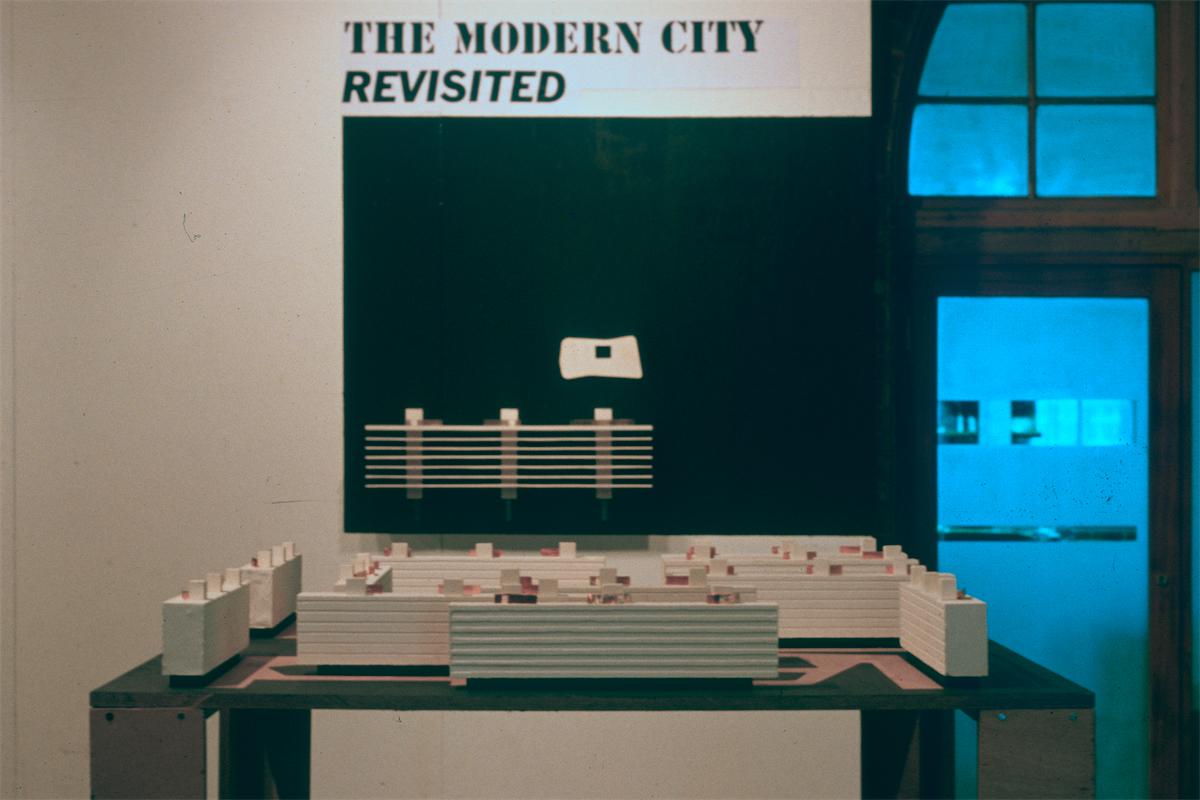

Thomas Deckker: Two Projects in Brasília

Architectural Design [Oct 2000]

Architectural Design [Oct 2000]

First International Seminar on the Teaching of the Built Environment [SIEPAC]

University of São Paulo, Brazil

13-15 Sept 2000

University of São Paulo, Brazil

13-15 Sept 2000

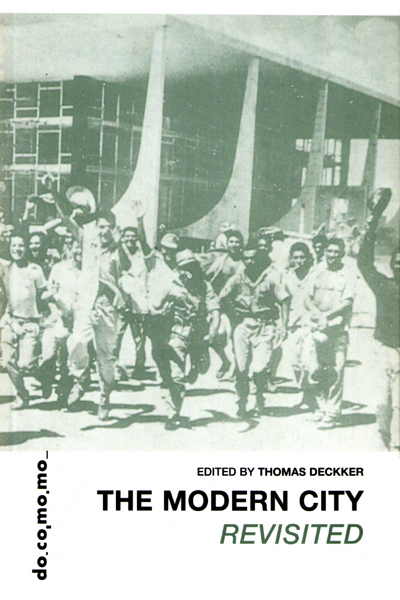

Issues in Architecture Art & Design

vol. 6 no. 1 [University of East London 2000]

vol. 6 no. 1 [University of East London 2000]

Thomas Deckker 'Land Art: City Architecture'

Monte Carasso: The re-invention of the site

Issues in Architecture Art & Design vol. 5 no. 2 [University of East London 1998]

Issues in Architecture Art & Design vol. 5 no. 2 [University of East London 1998]

Specific Objects / Specific Sites

Rethinking the Architecture / Landscape Relationship, University of East London,

26-28 Mar 1996

Rethinking the Architecture / Landscape Relationship, University of East London,

26-28 Mar 1996

Herzog & deMeuron

Issues in Architecture Art & Design vol. 3 no. 2 [University of East London 1994]

Issues in Architecture Art & Design vol. 3 no. 2 [University of East London 1994]

Herzog & deMeuron: Hebelstrasse Apartments, Basle

photograph © Thomas Deckker 1996

photograph © Thomas Deckker 1996

Herzog & deMeuron

Issues in Architecture Art & Design

The University of East London vol. 3 no. 2 1994

Wilfried Wang [ed.]: Herzog & deMeuron [StudioPaperback/Artemis Verlag, Zurich 1992]

Switzerland seems a strange country when viewed from post-Thatcher Britain. Clients - City Councils, the Federal Railways, public companies, and private individuals - have real needs and wide interests. Competitions produce good architecture. Buildings are renovated by retaining the floors and replacing the facades. Young architects are able to carry out projects ranging from small houses to urban regions; their work appears, from the British pragmatic and picturesque position, exceptionally brutal and esoteric.

It might be surprising, perhaps, that Switzerland, apparently as parochial as its representation in Graham Greene's The Third Man, has any good modern architecture. The present constitution was born out of the radical and reforming political consciousness of a society newly urbanised and industrialised in the late 19th century; the tourist view - Alpine pastures and laconic farmers - exists only through immense subsidies. Modern architecture has become linked to this modernisation of society. Of the first generation of Modern architects, although Le Corbusier left Switzerland, Alfred Roth and Robert Maillart, in Zurich, remained; Hans Zaugg and Haller & Haller, in Solothurn, became prominent in the 1950s; Atelier 5, in Bern, in the 1960s, and Mario Botta, Luigi Snozzi and Aurelio Galfetti, in Ticino, in the 1970s. Today, the culture and politics of the new Europe mean that the best architecture is produced in previously marginal cities such as Rotterdam, Barcelona, Oporto, and Basle. Basle is a major industrial centre; it lies on the border with both France and Germany, and its hinterland stretches into both these countries. Herzog & de Meuron, and numerous other practices, have flourished in this climate.

The inclusion of Herzog & deMeuron in the StudioPaperback series now is curious, however. This series, and its companion publications in Spain and Italy, serve well as an introduction to the work of acknowledged architects: Le Corbusier, Mies, Aalto, Wright, Jacobsen, Scarpa, and Kahn, as well as Aldo Rossi and Mario Botta. The format is detailed enough to appreciate the main aspects of the work, and comprehensive enough to serve as an inventory. Jacques Herzog and Pierre deMeuron, however, are only 42, and most of their more recent work is still unbuilt.

The early publication and small format have left several buildings incompletely described: there are no photographs of the interiors of the Blue House or the Goetz Gallery, which are available from other sources. Given the number of remarkable buildings promised for completion in the next two years, this volume will have to be updated shortly. The Spanish publisher Gustavo Gili included Herzog & deMeuron, perhaps more appropriately, in the slightly larger 'Catalogos de Arquitectura Contemporanea' series, with other contemporary European architects of international significance, such as Bach & Mora, Cruz & Ortiz, Francesco Veneziano, Aurelio Galfetti, and more recently, Hans Kolhoff and David Chipperfield.

Herzog and deMeuron graduated from the Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule in Zurich in 1975, the school at which Aldo Rossi was Professor of Planning from 1972 to 1975. Rossi seems to have been of critical importance to their development: Herzog and deMeuron have maintained his belief in the impossibility of communication in architecture in modern society, but instead of Rossi's reversion to pre-industrial archetypes, use a more sophisticated set of references - vernacular, suburban, Modern, and industrial architecture:

It might be surprising, perhaps, that Switzerland, apparently as parochial as its representation in Graham Greene's The Third Man, has any good modern architecture. The present constitution was born out of the radical and reforming political consciousness of a society newly urbanised and industrialised in the late 19th century; the tourist view - Alpine pastures and laconic farmers - exists only through immense subsidies. Modern architecture has become linked to this modernisation of society. Of the first generation of Modern architects, although Le Corbusier left Switzerland, Alfred Roth and Robert Maillart, in Zurich, remained; Hans Zaugg and Haller & Haller, in Solothurn, became prominent in the 1950s; Atelier 5, in Bern, in the 1960s, and Mario Botta, Luigi Snozzi and Aurelio Galfetti, in Ticino, in the 1970s. Today, the culture and politics of the new Europe mean that the best architecture is produced in previously marginal cities such as Rotterdam, Barcelona, Oporto, and Basle. Basle is a major industrial centre; it lies on the border with both France and Germany, and its hinterland stretches into both these countries. Herzog & de Meuron, and numerous other practices, have flourished in this climate.

The inclusion of Herzog & deMeuron in the StudioPaperback series now is curious, however. This series, and its companion publications in Spain and Italy, serve well as an introduction to the work of acknowledged architects: Le Corbusier, Mies, Aalto, Wright, Jacobsen, Scarpa, and Kahn, as well as Aldo Rossi and Mario Botta. The format is detailed enough to appreciate the main aspects of the work, and comprehensive enough to serve as an inventory. Jacques Herzog and Pierre deMeuron, however, are only 42, and most of their more recent work is still unbuilt.

The early publication and small format have left several buildings incompletely described: there are no photographs of the interiors of the Blue House or the Goetz Gallery, which are available from other sources. Given the number of remarkable buildings promised for completion in the next two years, this volume will have to be updated shortly. The Spanish publisher Gustavo Gili included Herzog & deMeuron, perhaps more appropriately, in the slightly larger 'Catalogos de Arquitectura Contemporanea' series, with other contemporary European architects of international significance, such as Bach & Mora, Cruz & Ortiz, Francesco Veneziano, Aurelio Galfetti, and more recently, Hans Kolhoff and David Chipperfield.

Herzog and deMeuron graduated from the Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule in Zurich in 1975, the school at which Aldo Rossi was Professor of Planning from 1972 to 1975. Rossi seems to have been of critical importance to their development: Herzog and deMeuron have maintained his belief in the impossibility of communication in architecture in modern society, but instead of Rossi's reversion to pre-industrial archetypes, use a more sophisticated set of references - vernacular, suburban, Modern, and industrial architecture:

our architecture stands in no real tradition with earlier architecture. It does, however, allude to it through observations, critical perceptions, copies of it or denials of it.

These references have been present since their earliest projects. The fractured shape and collaged plan of the Studio Frei, Weil, Germany (1981-82), seem to reflect its collection of references. Ironically for a function concerned with darkness, the building is given character by its windows: three enormous light-hoods recall those at La Tourette, while the horizontal windows on the entrance facade are deliberately suburban, as is the rear facade in roofing felt. The Blue House, Oberwil (1979-80), also plays with the type of suburban detached house, confronting it, however, with its colour - the blue used by Yves Klein - and skewed plan. The House for an Art Collector, Therwil (1985-86) has a suburban context, but the architects have refuted any gemütlichkeit with the use of a brutal construction system of pre-cast concrete panels. The Stone House, Tavole, Italy (1982-88), has free-stone walls that could almost be Italian vernacular, except that the concrete floor-slabs and cross-walls are expressed as a 'modern' frame.

This large body of work was completed by Herzog & deMeuron by the age of forty, which is remarkable compared to the paltry opportunities offered in Britain. Their later work happily occupies a more problematic territory, accompanying a move from the suburbs into the more sophisticated and demanding urban world. They have adopted a position of extreme rigour in design, combining forms without 'composition'. This exploration of the limits of architecture, which Rosalind Krauss calls the 'opposition to landscape', is closely related to that of certain contemporary sculptors, in particular Donald Judd. Although Herzog & deMeuron deny any direct influence from him (Judd exhibits frequently in Germany and Switzerland), they acknowledge a similarity in attitude.

The simplest built example of this approach to design is the Goetz Gallery, Munich (1989-92). The building is a simple rectangular block; the facade - two bands of glass separated by two of plywood - does not reveal the nature of the interior - two floors, partially buried. Scale is denied; the interior is devoid of external reference, with diffused glass in the windows. The entrance hall and services appearing as 'bridges' in the basement gallery. It seems ideally suited to the private collection it houses - mostly contemporary American Minimalism; as both Richard Serra and Tony Fretton have pointed out, the 'neutral white space' of the contemporary gallery is not 'value-free', but has a symbiotic relation to contemporary art.

This approach appears on a larger scale in the unsuccessful competition entry for the State Gallery for the Art of the Twentieth Century, also in Munich (1992). Individual enclosed galleries inhabit a large glass volume; external expression is reduced to a surface used to display information about the exhibitions. The Cultural Centre, Blois, France (1992-95) is more extreme: two auditoria are wrapped entirely by an electronic signboard. The themes of glass facades and block planning have been developed in a number of other recent projects: the Elsässertor office building (1990-95) and the Schwarz Park Apartments (1992-95) in Basle, and the Helvetia office building (1989) in St. Gallen, and in the upgrading of existing buildings: the SUVA office and apartment building (1988-93), and the Ciba-Geigy building K411 (1992) in Basle. These also reflect the growing importance of graphic and electronic communication in a more complex society. Curiously, Victor Hugo commented in 1832 in Notre Dame de Paris that the printed word had replaced architecture as the principle vehicle of communication, an idea taken up shortly after by Henri Labrouste for the facade of the Bibliothèque Sainte Geneviève, Paris (1843-50).

Such ideas could only remain unhappily outside the realm of a specifically architectural discourse without a significant material presence. In Switzerland, the high standard of living and rigorous climate necessitate a high standard of construction. Herzog & deMeuron exploit unusual combinations of industrial, as well as natural and 'poor' materials, and the logic of hand construction, rather than craftsmanship, which epitomise the post-industrial age:

This large body of work was completed by Herzog & deMeuron by the age of forty, which is remarkable compared to the paltry opportunities offered in Britain. Their later work happily occupies a more problematic territory, accompanying a move from the suburbs into the more sophisticated and demanding urban world. They have adopted a position of extreme rigour in design, combining forms without 'composition'. This exploration of the limits of architecture, which Rosalind Krauss calls the 'opposition to landscape', is closely related to that of certain contemporary sculptors, in particular Donald Judd. Although Herzog & deMeuron deny any direct influence from him (Judd exhibits frequently in Germany and Switzerland), they acknowledge a similarity in attitude.

The simplest built example of this approach to design is the Goetz Gallery, Munich (1989-92). The building is a simple rectangular block; the facade - two bands of glass separated by two of plywood - does not reveal the nature of the interior - two floors, partially buried. Scale is denied; the interior is devoid of external reference, with diffused glass in the windows. The entrance hall and services appearing as 'bridges' in the basement gallery. It seems ideally suited to the private collection it houses - mostly contemporary American Minimalism; as both Richard Serra and Tony Fretton have pointed out, the 'neutral white space' of the contemporary gallery is not 'value-free', but has a symbiotic relation to contemporary art.

This approach appears on a larger scale in the unsuccessful competition entry for the State Gallery for the Art of the Twentieth Century, also in Munich (1992). Individual enclosed galleries inhabit a large glass volume; external expression is reduced to a surface used to display information about the exhibitions. The Cultural Centre, Blois, France (1992-95) is more extreme: two auditoria are wrapped entirely by an electronic signboard. The themes of glass facades and block planning have been developed in a number of other recent projects: the Elsässertor office building (1990-95) and the Schwarz Park Apartments (1992-95) in Basle, and the Helvetia office building (1989) in St. Gallen, and in the upgrading of existing buildings: the SUVA office and apartment building (1988-93), and the Ciba-Geigy building K411 (1992) in Basle. These also reflect the growing importance of graphic and electronic communication in a more complex society. Curiously, Victor Hugo commented in 1832 in Notre Dame de Paris that the printed word had replaced architecture as the principle vehicle of communication, an idea taken up shortly after by Henri Labrouste for the facade of the Bibliothèque Sainte Geneviève, Paris (1843-50).

Such ideas could only remain unhappily outside the realm of a specifically architectural discourse without a significant material presence. In Switzerland, the high standard of living and rigorous climate necessitate a high standard of construction. Herzog & deMeuron exploit unusual combinations of industrial, as well as natural and 'poor' materials, and the logic of hand construction, rather than craftsmanship, which epitomise the post-industrial age:

The architectural product has for a long time been the product of no craftsman. But already it is no longer a purely industrial one either.

The results of this mixture of industrial products and hand construction are as beautifully made and highly finished as the steelwork of Haller & Haller, or the beton brut of Atelier 5. The meticulous construction of the facade of the Ricola warehouse, Laufen (1985-86), in alternating vertical and horizontal courses of fibre-cement sheets, seems almost to be transparent, and to reveal the system of storage racks within. In the Hebelstrasse Apartments (1984-88), the tapering wood columns and over-sailing roof constitute an additional, almost detached timber facade. The Railway Signal Box, Auf dem Wolf, Basle (1988-95) is a concrete box enclosed in copper slats, twisted to allow illumination, which forms a sensuous outer skin.

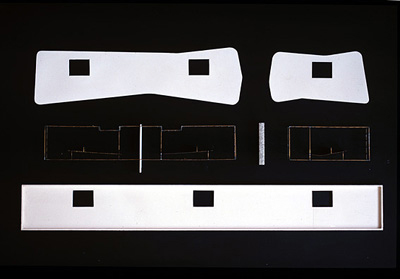

Many of the unbuilt projects are presented as deliberately rough wooden models. Herzog & deMeuron's model-making techniques are intimately linked to their conception of architecture:

Many of the unbuilt projects are presented as deliberately rough wooden models. Herzog & deMeuron's model-making techniques are intimately linked to their conception of architecture:

'White models'... are supposed to be 'neutral', they, in fact, reduce architecture to volume and geometry.

These models appear as analogies to the final work, referring to densities, materials, and textures. Their drawing style, too, is very austere, and deals with conceptual, rather than physical, matters:

Architectural pictures... are even more impossible than the neutral white models... the more naturalistic, the more deceptive is its intention.

Some critics have drawn parallels between Herzog & deMeuron's early work and that of 'weak' Swiss Modernists such as Hans Bernoulli, and there are indeed similarities between their Schwitter Building and Bernoulli's Realgymnasium, Basle, or their Pilotengasse Housing, Vienna and his Tülingerstraße Housing, Basle. For Herzog & deMeuron, however, using conventional form is an extreme, rather than a compromise, position. The real motive seems to be a nostalgia for the extreme programmatic and aesthetic sensibilities of early Modern architects. The pre-cast concrete panel construction of the Therwil House and the Schwitter building was previously used by Max Bill in his Weekend House, Bremgarten (1930); the Ricola factory canopy (1989-91) has the same extreme cantilever as Hannes Meyer's School project, Basle (1926). There are also references to International Modern architecture: the block planning recalls Aalto's Pensions Institute in Helsinki (1948-56); the Berlin Zentrum project (1990), four enormous rectangular blocks surrounding the Tiergarten, recalls Mies' project for the Alexanderplatz (1928).

Adolf Loos is, of course, the common foundation of much of this thought. Many contemporary issues, whether of the relevance of architecture to society, or the role of craftsmanship in architecture, were rehearsed in fin de siècle Vienna. Much of the interest of Herzog & deMeuron's work lies in the provocative position it takes in relation to the society which appears to support it so generously:

Adolf Loos is, of course, the common foundation of much of this thought. Many contemporary issues, whether of the relevance of architecture to society, or the role of craftsmanship in architecture, were rehearsed in fin de siècle Vienna. Much of the interest of Herzog & deMeuron's work lies in the provocative position it takes in relation to the society which appears to support it so generously:

The architectural plan and the architectural work interest us as tools for the perception of reality and confrontation with it.

This grounding questions the usual role of the author of the architectural work. In Britain there has been a polarisation between those who believe that caricatures of classical architecture 'represent' our society, and those with an unshakeable belief in technology; the reaction of many contemporary architects has been a flight to an Empirical and picturesque position. Herzog & deMeuron propose a Rational alternative; they believe that the "ludicrous particularity of the author" has led to an preposterous situation in practice:

Never in the history of architecture has there been such a crass loss of orientation for architects as now. Never, too, was there so much terrible architecture as there is today.

Their architecture is instead, they believe:

comprehensible only through itself, without crutches, only manufacturable from architecture, not from anecdotes or quotations or functional systems.

These observations must remain critical speculation in the absence of built work. The smaller projects and public housing seem to have achieved a balance between restraint and delight; the planning is deliberately practical and undemonstrative, skirting the problematic territory of the author, while retaining architectural integrity. Whether the reduction in architectural experience and the reliance on graphic and electronic communication are appropriate at an urban scale remains to be proved. The conclusion must surely be that, in this StudioPaperback volume, Herzog & deMeuron appear very much as authors, sensitive to site, ruthless with programme, and inventive with materials. The absence of further built work will remain, hopefully, brief.

Thomas Deckker

London 1994

London 1994