Architectural Design [Oct 2000]

I first visited Brasilia in 1985 shortly after the deposition of the military government, when it seemed that the euphoria of the return to democracy - to the great project of the Modernisation of the country which ran from 1930 to the coup in 1964 - might spill over equally into euphoria about Modern architecture.

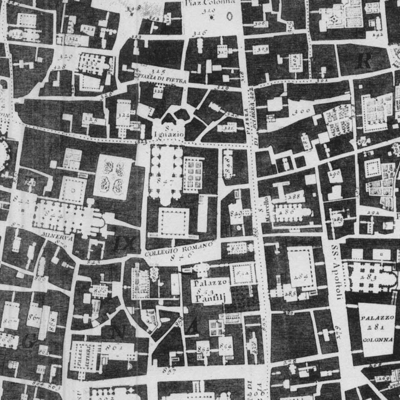

Brasilia is the city which comes closest to realising the dream of Modern urbanism. It is equally distant from its ambitious suburban contemporaries, Canberra or Milton Keynes, as it is from the ubiquitous Modern fragments which every European city contains. Visiting the city only 25 years after its inauguration - and already an historical artefact - made me aware of something beyond the fact that the Modern project - architectural and political - was dead. What was built was certainly courageous and beautiful, but what was ignored eventually undermined its foundations to the extent that the completion of Brasilia - the symbol of Brazilian modernity - brought 21 years of military dictatorship and the end of modern architecture to Brazil.

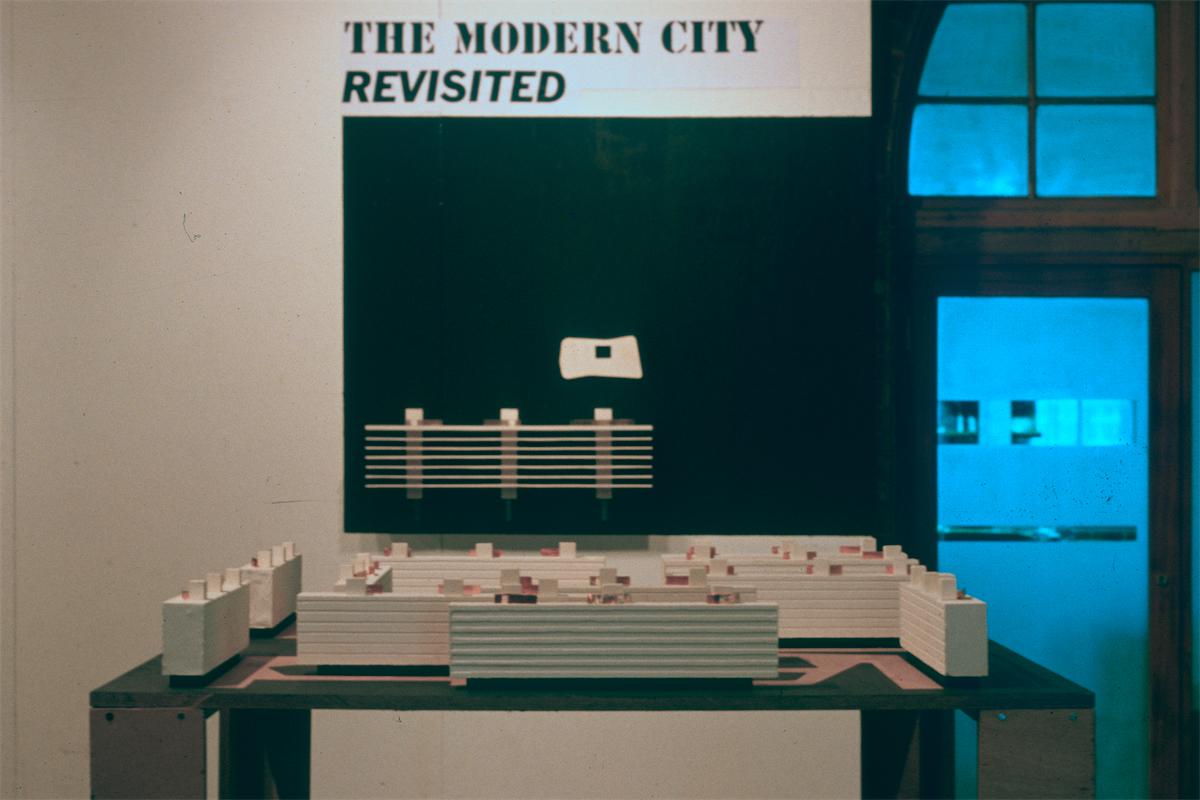

At the time, however, what struck me most was the extraordinary amount of left-over space that had been created as consequence of the design of the city. Some spaces could hardly be avoided - such as the huge landscape spaces within the city itself, which resisted the urbanity of the city. Others needed to be sniffed out, such as roofs of the superquadras - the groups of apartment blocks, which were a by-product of the reductivism of Modernism. The roofs formed uniform platforms six storeys above ground level, usually articulated in each block by three two-storey lift towers.

This roof landscape seemed not only to be architecturally incomplete, but analogous to another very distant and supposedly natural landscape in England - that of Blakeney Point on the north Norfolk coast. The shifting sand dunes there are propagated and stabilised by rows of wooden stake fences; in other words, the landscape is formed by the architecture. The sand-fences formed spaces among themselves and between themselves and the landscape, a possibility of architecture I thought appropriate to investigate on the roofs of the superquadras.

To make the roofs inhabitable required only one small addition of architecture to this analogous landscape: a wall placed against each lift tower to define 'front' and 'back', or 'social' and 'service' sides. The single wall in each apartment was intended to be made of the beautiful sucupira wood similar to the walls in Niemeyer's palaces which play such an important part in the extension of interior space out into the landscape. The only other elements required would be a continuous curtain of light-weight glazing for the external walls and a free-form concrete roof. The sun shines directly overhead, and thus the roofs would cast long shadows down the blocks out of all proportion to their visibility from the ground.

This project had a political dimension, too. My intention was to add a layer of difference to relieve the social uniformity of the superquadras brought about by the uniformity of types of inhabitation. Making an inhabitable layer on the top - necessarily for the more sophisticated - was a discerning reflection, I thought, of the occupation of the ground floor by the - unfortunately poor - porters. Just as the domestic space of the apartments is necessarily serviced by maids, the urban space of the blocks is necessarily surveyed and controlled by porters.

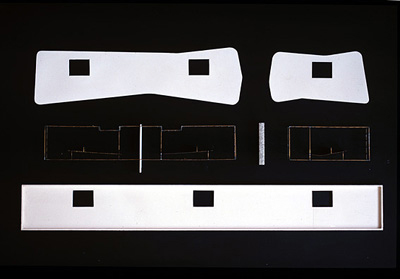

Following the restoration of some apartments in the superquadras, I was commissioned to design a house in the lago sul. This area of the city, bordering the lake, was originally designated for the political class - ministers, diplomats and other officials - but has since expanded exponentially to include the generally wealthy. The ubiquitous 'executive' homes which have cropped up take their inspiration from the incredibly influential TV novelas [soap operas], which depict the fantastically exaggerated fictional lives of the super-rich in Sao Paulo. Euphemistically described as 'colonial', the houses are without exception badly planned, dark and stuffy. The starting point for my client was their discomfort with these claustrophobic corridors, which was happily in accord with my own desire to make the centre of the house a space of shifting definition - from entrance hall, to central circulation space, to part of the living room, and to open all rooms off it. The wall on one side is clad with boards of frejo, and is cut and folded to provide almost a map of the main spaces of the house. This wall reminded me of a disassembled boat I had seen in the National Maritime Museum, in which the 3-dimensional form of the boat was implicit in the spaces between the strakes. The hall is lit and ventilated by a long skylight, which is greatly appreciated by the clients:

Brasilia is the city which comes closest to realising the dream of Modern urbanism. It is equally distant from its ambitious suburban contemporaries, Canberra or Milton Keynes, as it is from the ubiquitous Modern fragments which every European city contains. Visiting the city only 25 years after its inauguration - and already an historical artefact - made me aware of something beyond the fact that the Modern project - architectural and political - was dead. What was built was certainly courageous and beautiful, but what was ignored eventually undermined its foundations to the extent that the completion of Brasilia - the symbol of Brazilian modernity - brought 21 years of military dictatorship and the end of modern architecture to Brazil.

At the time, however, what struck me most was the extraordinary amount of left-over space that had been created as consequence of the design of the city. Some spaces could hardly be avoided - such as the huge landscape spaces within the city itself, which resisted the urbanity of the city. Others needed to be sniffed out, such as roofs of the superquadras - the groups of apartment blocks, which were a by-product of the reductivism of Modernism. The roofs formed uniform platforms six storeys above ground level, usually articulated in each block by three two-storey lift towers.

This roof landscape seemed not only to be architecturally incomplete, but analogous to another very distant and supposedly natural landscape in England - that of Blakeney Point on the north Norfolk coast. The shifting sand dunes there are propagated and stabilised by rows of wooden stake fences; in other words, the landscape is formed by the architecture. The sand-fences formed spaces among themselves and between themselves and the landscape, a possibility of architecture I thought appropriate to investigate on the roofs of the superquadras.

To make the roofs inhabitable required only one small addition of architecture to this analogous landscape: a wall placed against each lift tower to define 'front' and 'back', or 'social' and 'service' sides. The single wall in each apartment was intended to be made of the beautiful sucupira wood similar to the walls in Niemeyer's palaces which play such an important part in the extension of interior space out into the landscape. The only other elements required would be a continuous curtain of light-weight glazing for the external walls and a free-form concrete roof. The sun shines directly overhead, and thus the roofs would cast long shadows down the blocks out of all proportion to their visibility from the ground.

This project had a political dimension, too. My intention was to add a layer of difference to relieve the social uniformity of the superquadras brought about by the uniformity of types of inhabitation. Making an inhabitable layer on the top - necessarily for the more sophisticated - was a discerning reflection, I thought, of the occupation of the ground floor by the - unfortunately poor - porters. Just as the domestic space of the apartments is necessarily serviced by maids, the urban space of the blocks is necessarily surveyed and controlled by porters.

Following the restoration of some apartments in the superquadras, I was commissioned to design a house in the lago sul. This area of the city, bordering the lake, was originally designated for the political class - ministers, diplomats and other officials - but has since expanded exponentially to include the generally wealthy. The ubiquitous 'executive' homes which have cropped up take their inspiration from the incredibly influential TV novelas [soap operas], which depict the fantastically exaggerated fictional lives of the super-rich in Sao Paulo. Euphemistically described as 'colonial', the houses are without exception badly planned, dark and stuffy. The starting point for my client was their discomfort with these claustrophobic corridors, which was happily in accord with my own desire to make the centre of the house a space of shifting definition - from entrance hall, to central circulation space, to part of the living room, and to open all rooms off it. The wall on one side is clad with boards of frejo, and is cut and folded to provide almost a map of the main spaces of the house. This wall reminded me of a disassembled boat I had seen in the National Maritime Museum, in which the 3-dimensional form of the boat was implicit in the spaces between the strakes. The hall is lit and ventilated by a long skylight, which is greatly appreciated by the clients:

In the morning the sun scintillates in the skylight and the house lightens as if we were outdoors. At certain times we simply encounter a full moon, exhibiting itself gratuitously...

Great attention had to be paid to light and view on the narrow suburban site:

There is an integration, almost a continuity, between the interior of the house and the garden. From the study I can see the children playing outside. From any space it is possible to have a view of the sky, stars, moon, sun and garden. It is a wonderful feeling of freedom and well-being...

Two systems of organising spaces are used to bring some sense of order to the house. The first, used in the open-plan spaces, is a series of very large cupboard units used to separate different areas in the living room, study and master bedroom (these are still unfinished). The second, used in the bedrooms on both the larger and smaller side of the house, is a sequence of cupboard / bathroom / balcony which gives each bedroom a secure outdoor space.

To make this house environmentally responsive, virtually all the technologies used in its construction had to be invented or rediscovered. Heavy insulated construction makes the house cool and calm. Unusually for Brasilia, the house has running hot water from a solar heating system, and the air-conditioning is restricted to the master bedroom and study. In the other bedrooms, cross-ventilation is facilitated by the traditional bandeiras (louvered panels) over the doors. Balconies are protected (against both sun and burglars) by sliding steel louvered brise-soleils.

Fortunately, all involved overcame the problems of working with an architect based in London, and we were able to achieve an extraordinarily high standard of workmanship. The main part of the house was constructed with a master of works and the finishing stages directly with various contractors. Almost all fittings had to be purpose made, from windows and doors to the main lighting control panels, and we were fortunate in finding an enthusiastic commitment to the standards required.

To make this house environmentally responsive, virtually all the technologies used in its construction had to be invented or rediscovered. Heavy insulated construction makes the house cool and calm. Unusually for Brasilia, the house has running hot water from a solar heating system, and the air-conditioning is restricted to the master bedroom and study. In the other bedrooms, cross-ventilation is facilitated by the traditional bandeiras (louvered panels) over the doors. Balconies are protected (against both sun and burglars) by sliding steel louvered brise-soleils.

Fortunately, all involved overcame the problems of working with an architect based in London, and we were able to achieve an extraordinarily high standard of workmanship. The main part of the house was constructed with a master of works and the finishing stages directly with various contractors. Almost all fittings had to be purpose made, from windows and doors to the main lighting control panels, and we were fortunate in finding an enthusiastic commitment to the standards required.

Thomas Deckker

London 2000

London 2000