Luigi Snozzi: Monte Carasso, Bellinzona

photograph © Thomas Deckker 1996

Luigi Snozzi: The re-invention of the site

A review of Luigi Snozzi: Monte Carasso: die Wiedererfindung des Ortes / Monte Carasso: la reinvenzione del sito [Birkhäuser, Basle 1995]

published in Jan Birksted (ed): Relating Landscape to Architecture [London: Routledge 1999]

From the terrace of the Castelgrande in Bellinzona one can look across the Ticino valley and see, almost on axis on the opposite hillside, a house by Mario Botta. The Botta house is a cool, abstract object meticulously constructed in concrete blockwork, a sharp contrast to the surrounding suburban development of the valley. Botta has been famous for almost 25 years, and his works have been objects of pilgrimage by visiting architects for at least as long. Architects - quite rightly - have been repelled by the ubiquitous suburban development of the valley - mostly in 'representational' styles found anywhere in Europe; Ticino is under enormous pressure as a holiday playground. In publications of Botta's work - and thus even more shocking in reality - these surroundings have been largely edited out.

Yet one can visit the work of another generation of architects in Ticino - Luigi Snozzi and Aurelio Galfetti - who engage these surroundings. Why one might want to do this signifies, perhaps, the central concern in architecture today. The difference between Botta, on the one hand, and Snozzi and Galfetti, on the other, might be said to mark a division between generations of architects as much as of visitors; it is principally an attitude to site: and site, today, means the city. While Botta necessarily presumed an amorphous site for his geometrical objects, Snozzi and Galfetti are concerned with the problematic areas of reconstruction and urban margins in which context must be recognised.

Botta's works are, of course, of supreme integrity. Botta (b. 1943) is truly a Modern wunderkind: working for Le Corbusier on the Hospital project (1965) and for Louis Kahn on the Palazzo dei Congressi project (1969) while studying under Carlo Scarpa, all in Venice. These influences appear even in his early work, such as the House in Riva San Vitale (1971-73), the magisterial School in Morbio Inferiore (1972-77), or the Library for the Capuchin Convent in Lugano (1976-79). His sensibilities of construction - in the 'poor' materials of concrete blockwork and fair-faced concrete, of the structuring of form and space, and of natural light, are sublime in their intensity.

Not all of Botta's recent work, however, has been so successful. The Swiss Bank Union (1986-91) in Basle - where every other building seems to be a bank anyway - is simplistic and vulgar; the new Cathedral (1988-93) in Evry is pompous. Botta seems to have been carried away by an excess of geometry. Such is his veneration of Le Corbusier that he has published a collection of writings and sketches in flagrant imitation of Le Corbusier - surely the height of pretension. On the other hand, several of Botta's more successfully-planned urban design projects have been undertaken in collaboration with Snozzi - the Management Centre in Perugia (1971) and Zürich Railway Station (1978), and Galfetti - the Conference Centre in Marseilles (1988).

Snozzi's and Galfetti's upbringings have been far more modest. Snozzi (b. 1932) studied at the Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule [ETH] in Zurich from 1952 to 1957; he worked briefly for the architect Rino Tami in Lugano, who was to design the St. Gotthard autostrada in the 1960s. Since then, he has supported his meagre commissions with teaching at the ETH in Zurich and Lausanne. Galfetti (b. 1936) worked for Tita Carloni, another important Ticino architect, in 1957, before studying at the ETH. He, too, has been reliant on teaching at Lausanne. Despite the limited geographical area of their practice - essentially between Locarno and Bellinzona - and apparently limited opportunities - these architects have managed to build some very provocative work.

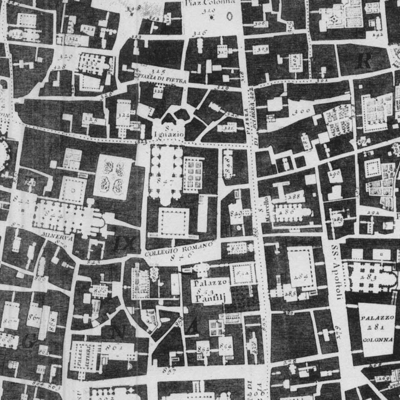

The re-construction of the Castelgrande in Bellinzona (1980-92) is probably Galfetti's best-known work. It is truly a re-construction, as the original castle had virtually disappeared under centuries of spoil. It knits the castle into the fabric of the town, principally via the famous elevator, while providing some indispensable functional spaces such as a restaurant and museum. It is a work in many ways comparable to Scarpa's re-construction of the Castelvecchio (1956-73) in Verona: clear distinctions have been made between new and old, while both have served the creation of new uses and places. The Castelgrande is rather more modest historically and architecturally than the Castelvecchio, and the degree of dereliction much greater, and consequently the re-construction has been less about uncovering the historical and architectural density than in the straight-forward creation of new places within the fabric. This is the major divergence from Scarpa: Galfetti has reconstructed parts of the original fabric, and some of the site, to accentuate its spatial continuities.

As one moves from the terrace to the entrance courtyard of the Castelgrande, a series of sites unfolds below: vacant sites among nineteenth-century villas, unused and unfashionable historical buildings, the flood plain of the Ticino river. These are the typical marginal sites of the contemporary European city, and it is these which are the place of the work of Galfetti and Snozzi. Directly beneath the castle, among the nineteenth-century villas, are Galfetti's 'Bianco e Nero' apartment buildings (1986-87) ; on the flood plain are his Swimming Pool (1967-70) and Tennis Club (1984-86), part of a development plan in which structure was given to this amorphous area by robust concrete walls and geometrical plan shapes. Botta's Telecommunications Headquarters (1988-92) - a broken square in red-brick - is, thankfully, basic and unpretentious.

Across the Ticino river lies the suburb of Monte Carasso. The development of Monte Carasso has been dominated since 1978 by Snozzi, who used it as a test-bed for his ideas on the construction of urbanity, and it is this "grande avventura " which is described in Monte Carasso: die Wiedererfindung des Ortes / Monte Carasso: la reinvenzione del sito . The cantonal piano regolatore envisaged it as a dormitory suburb of Bellinzona - a low-density centre-less agglomeration - but Snozzi, at the invitation of the comune, proposed an alternative: a definitive centre, and an increase in the density of the facilities and the fabric. The wishes of the comune were facilitated by three things: firstly, the patent benefits of Snozzi's plan; secondly, the determination and resources of the mayor and the local inhabitants; and thirdly, the willingness of the planners to let the piano regolatore be guided by specifically architectural proposals. Snozzi defined his objectives for the new works as:

I nuovi interventi devono essere effetuati nel rispetto della struttura architettonica e urbanistica esistente e comunque nel confronto con la stessa.

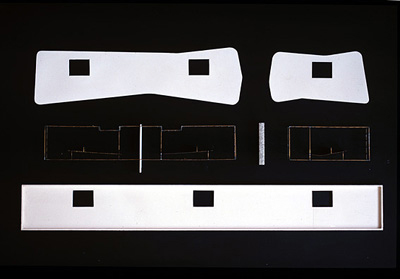

That is, they must simultaneously respect the existing architectonic and urban structure and establish a confrontation with it. There is a total rejection of historicism in their design and relation to site; they are placed in a purely topographical manner. This is, for Snozzi, the central issue of architecture: that the focus of interest in a work is the relations it enters into with its site, and not the work itself; it is a metaphor for the political relations of its inhabitants to the city. To emphasise its topographical relations, Snozzi has stripped his work of all extraneous references, whether formal - he uses only basic cubic shapes, or constructional - although his works are beautifully made in in-situ concrete; experience of the buildings reveals how these are animated by light, view, and movement.

Luigi Snozzi: Kalman House, Locarno

photo © Thomas Deckker 1996

This design vocabulary may be found equally in the holiday house of a wealthy patron, such as the Kalman house (1975) in Locarno, or to low-cost housing; Snozzi was well known for his houses long before the plan for Monte Carasso. The Kalman house, for example, is concrete box with one open end; it recalls Le Corbusier's maison 'Citrohan' (1920), with the solarium removed and placed on the site as a pergola. But Snozzi's apparent involvement with Modernism is not a simple transformation; while the maison 'Citrohan' was a metaphor for, as well as product of, the machine age, the Kalman house is material and experiential. The house is organised around a curved retaining wall, which distorts the open end of the box and extends out to form a pergola overlooking Lago Maggiore. The staircase runs through a three-storey-high light-filled void along this retaining wall (the entrance is at basement level). There is no distinction between columns and walls - all surfaces, except the floor in red tiles, are in rendered concrete.

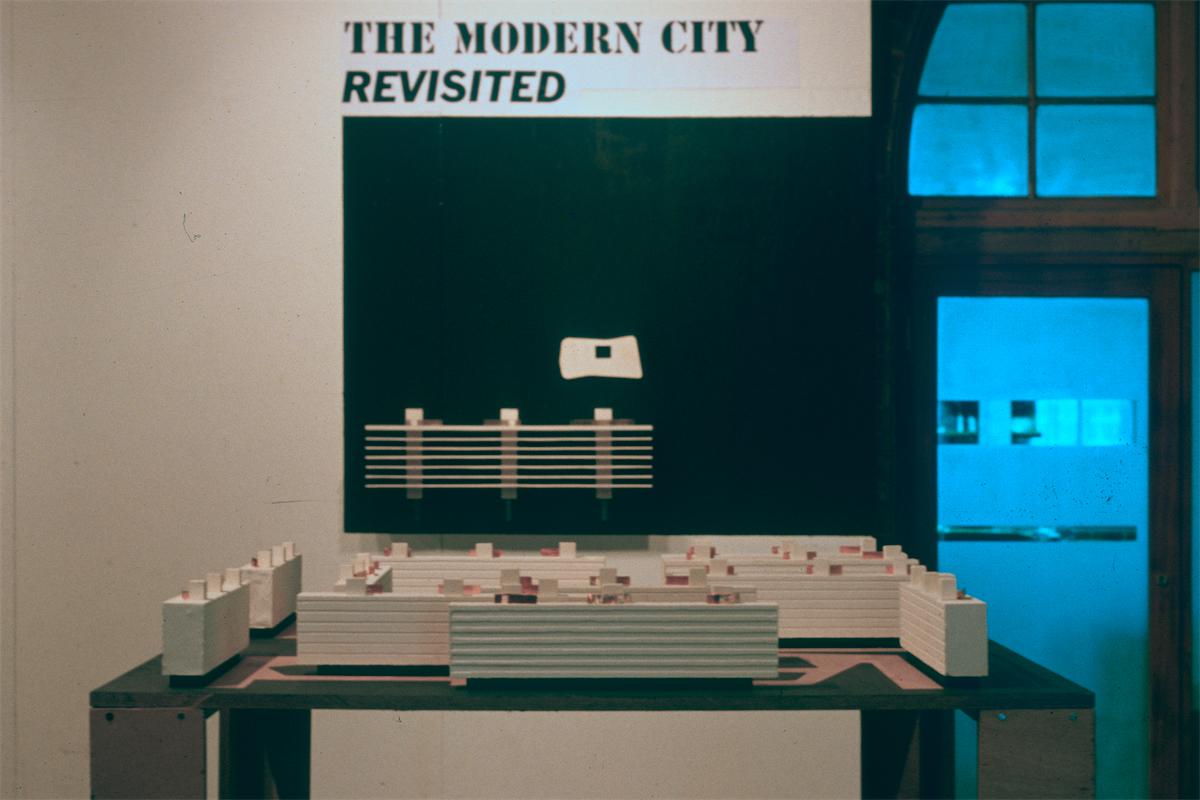

This attitude to topography may also be seen in a major scale in Monte Carasso. To create a centre for Monte Carasso, Snozzi proposed to site a new school, with a church and mayoral offices, around a piazza within a former Augustine convent, which had been completely submerged beneath nineteenth-century developments. Such is the success of the piazza that it is now used for summer festivals. The convent has been restored in a manner reminiscent of Scarpa's re-construction of the Castelvecchio or Galfetti's of the Castelgrande, with very clear new elements juxtaposed against the old fabric. The new fabric of the school - the enormous light hoods over the classrooms (could these be derived from Le Corbusier's Venice Hospital project?) not only act as a new, serial, form to be read against the existing fabric, but are inhabitable as separate study areas within each classroom. Other buildings were placed around the convent to reinforce its presence: the Palestra (1979-84) - a gymnasium, the so-called Casa del Sindaco (1984) - actually the Casa Guidotti - the mayor's house, and the Banca Raiffeisen (1984). The gymnasium is a glorious light-filled basilica reminiscent of Kahn; here the comune, to enable Snozzi's scheme to be realised, refused a subsidy on its construction costs from the army, who wanted to use it - with certain modifications - for military training.

In place of the low-density residential development envisaged in the piano regolatore, with houses set in the middle of their plots, Snozzi proposed such planning heresies as 'filling in' between existing houses to increase the density - such as the Casa Marisoli, and reinforcing the definition of the town - such as the Casa Briccola - a tower house - by Snozzi's pupil Ricardo Briccola. The edge of the town adjacent to the autostrada is further defined by a long wall of low-cost housing, the 'Quartiere Monrenal' currently under construction. These new forms were approved by assessing two proposals - one following the piano regolatore, the other as Snozzi preferred. No cases of dissent are recorded. It may seem surprising - if not unbelievable - that the cantonal planners were prepared to alter the piano regolatore to agree with specifically architectural proposals; they had already shown an awareness, however, of the special nature of the landscape in Ticino in the design of the St. Gotthard autostrada, which runs through the entire valley (and separates Monte Carasso from Bellinzona).

The use of serial forms, such as the light hoods at the convent, must be understood as a specifically contemporary form of composition, as against the hierarchical and symmetrical form of the 17th-century convent. This is brought out clearly in drawings showing the original - axial - and reconstructed - serial - plans of the convent. Snozzi blurs the distinctions of sculpture, architecture, urbanism, and landscape design. His approach links him to artists such as Richard Serra and Donald Judd; his work would not look out of place among Judd's '15 Concrete Boxes' (1979) at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa.

What, then, is the value of Snozzi's work? The 'European city' so provocatively proposed by Rossi in the 1960s had by the 1970s become the site of the public display of consumption, the apotheosis of the consumer society. A statement by Guy Debord springs to mind:

The entire life of those societies in which modern conditions of production prevail presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. All that was once directly lived has become mere representation.

Snozzi's work is the architecture of resistance to the spatial and environmental degradation of the consumer society. He seeks to re-establish personal relations with collective urban life. He chooses to do this in a progressive, rather than a regressive manner: a rejection of historicism in favour of experience through form, material, light, view, movement, and topography.

Thomas Deckker

London 1998