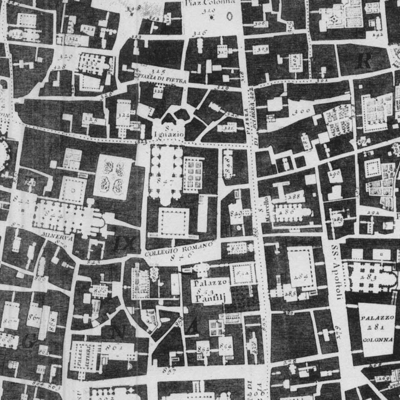

In the Park Central Hotel in downtown Fort Worth there is an intriguing photograph. John Fitzgerald Kennedy spent the night of 21 November 1963 at the Hotel Texas there before continuing on to Dallas; the photograph shows him mobbed by supporters outside the hotel in his - fatally unprotected - limousine. When one turns and looks out the window the same street is unrecognisable. Instead of the dense blocks of offices, hotels and department stores in the photograph there is an open grid of parking lots; only a few isolated buildings remaining.

The transformation of American cities has been viewed as a natural phenomenon, as a 'survival of the fittest' - not least by its beneficiaries - that it is, perhaps, a surprise to find the quantity of opinion directed against its assumptions. No city other than Los Angeles has been the subject of so much critical attention, most famously, perhaps, by Edward W. Soja, Frederic Jameson, Lynne Spigel and Mike Davis, to the point where it has become a metonym for disastrous urban development. Davis in particular has charted the future decline of Los Angeles through its own 'internal contradictions': by social division in City of Quartz: excavating the future in Los Angeles (1990), by courting natural disaster in Ecology of fear: Los Angeles and the imagination of disaster (1998), and by the displacement of the Anglo population by the Hispanic in Magical Urbanism (2000). Finally, in Dead Cities and other tales (2002), Davis extends his metaphorical description of capitalism as war to American landscapes and cityscapes.

Davis's thesis in Dead Cities and other tales is how American capitalism - insane and unfettered greed, endemic racism against Negroes, Hispanics and Native Americans, and the collusion of government, monopolistic industries and an unaccountable military, has brought not only Los Angeles but the whole Southwest to the brink of environmental disaster- not least because of the nuclear, chemical and biological development sites - and social adversity. The parallels Davis draws to the expansion and suburbanization of Los Angeles that began during the Second World War are intriguing. He notes that, in 1942, the US Army was building (and rebuilding) full-size models of the centres of Berlin (advised by Erich Mendelsohn) and Tokyo (advised by Antonin Raymond) in Nevada to perfect the destruction of their civilian populations and urban cultures by aerial bombardment. I am sure we are all familiar with photographs of the results.

Few downtowns, however, could look a devastated as that of Houston. Houston is, in many respects, a more extreme but less glamorous version of Los Angeles. It stretches towards Galveston, much as London stretches towards Brighton, but with only 2 million inhabitants; its density is one quarter that of Los Angeles. Lars Lerup and Albert Pope, Dean and Professor respectively at Rice University, have both found a less apocalyptic critical voice for their city. Pope fully deserves to join Soja and Jameson; in Ladders, he provides a precise analysis of how 20th-century suburbanization developed along closed 'ladder' grids, that is, cul-de-sacs along freeways, rather than 19th-century open rectilinear grids. This new and parallel sub-urbanism could hardly be said to be a populist reaction to architectural theory: it was partly based on the English Garden City ideal of Ebenezer Howard in the 1890s and Barry Parker & Raymond Unwin in the 1900s and on its later development by Ludwig Hilbersheimer in the 1940s (Richard Neutra was also implicated). Pope, quoting the Second Law of Thermodynamics, concludes that entropy, a condition of 'chaos and sameness' has replaced 'organisation and differentiation' as the paradigm of the urban condition.

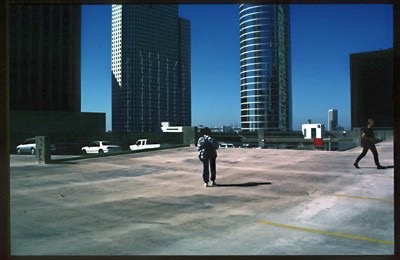

How that entropic urban condition is articulated is described by Lerup in The City after Tomorrow, an enlargement of the thesis first published as 'Stim & Dross: Rethinking the Metropolis' in assemblage in 1994: that out of a 'zoomorphic field' of dross ('dregs'), occasional stims ('stimulations', or from the German Stimme, 'voice') occur which, borrowing an analogy from chaos theory, briefly act as 'strange attractors' for urban life. Such stims have no use for architecture: they are social rather than spatial. George O. Jackson's photographs - freeways, vacant lots, parking - revisit the territory of Robert Smithson and Ed Ruscha. Pope calls this the 'aesthetic of emptiness'.

No visitor to Houston, however, particularly if they are visiting Renzo Piano's Menil Collection, could fail to be impressed by the 'Museum District' in which it is found. The 'Museum District' is a an area of mixed use par excellence: middle class homes, museums, Rice University itself, restaurants, shops, with a prosperous Hispanic district adjacent. This is the area which Lerup calls the 'middle landscape', an indeterminate zone inside the inner freeway loop, between downtown and suburbs, and squalor and growth. This 'middle landscape' has developed without the formal architectural theories and corporate construction system of the suburbs, but rather through co-operative anarchy; it is an 'open' system of creation rather than the 'closed' system in which entropy is inevitable. It will be strangely familiar to the inhabitants of London.

If violence, turmoil, greed and ignorance are the factors Davis sees as ensuring the decline of American cities, they are exactly those which Peter Ackroyd believes have ensured London's rise to world prominence. From this viewpoint the well-meaning but patronising Abercrombie plan seems surely a fleeting aberration in a Darwinian struggle. Darwin's thesis was, of course, not 'the survival of the fittest' popularly supposed by theoreticians of capitalism but survival through adaptation to changing environments. In London - The Biography Ackroyd charts the growth of what used to be known as the 'Modern Babylon' and its decline after the Second World War, partly a result of it emptying into the Garden Cities and New Towns beyond the Green Belt. The 'aesthetic of emptiness' governs London as much as Houston; if it necessarily needs its 'other', then it surely has created it along the M25, a bizarre world of insane asylums, military establishments and secretive corporations mapped out by Iain Sinclair in London Orbital: A Walk Around the M25. Yet Ackroyd's final chapter is 'Resurgam'. The return of London to a kind of co-operative anarchy may be, instead of its decline, a sign of its survival in the late capitalist world.

thomas

deckker

architect