When the Architectural Review noted in 1954 that 'to the European architect few creatures could look as fabulous as his Brazilian counterpart as he appears in the stories which filter back from Rio - of men with Cadillacs, supercharged hydroplanes, collections of modern art to make the galleries blush, bikini-clad receptionists and no visible assistants' they must have had in mind one particular architect: Oscar Ribeiro de Almeida de Niemeyer Soares.

Niemeyer was born in 1907 into a patrician but modest family and brought up in Laranjeiras, a district of Rio de Janeiro of solid houses with high-ceiling rooms and large gardens shaded by palm trees hardly changed from the pictures of Debret. Niemeyer felt architecture as vocation. He studied at the Escola Nacional de Belas Artes, including a year during Costa's short-lived 'Functional' course. Unwilling to compromise with current commercial architectural practice, upon his graduation in 1934 he became an assistant to Costa who, having himself converted to Modernism, was enduring five years with almost no work. It must not have been an easy decision: Rio was then undergoing a boom, due equally to the programme of national self-sufficiency and to the Agache Plan for the reconstruction of the centre. It was, as Philip Goodwin, author of Brazil Builds, noted in 1942, part Paris and part Los Angeles. While architecture was conservative, engineering was very dynamic: the 'A Noite' building, where Costa had his office, was the tallest reinforced-concrete structure in the world. According to Costa, the young Niemeyer displayed no special aptitude for architecture.

Niemeyer learnt all he needed to know about the Modern architectural language in a few weeks in August 1936 during Le Corbusier's brief visit to Brazil as adviser on the Ministry of Education. Such was the confidence he gained that he was able to take the Corbusian formulation of Modernism and turn it into a highly sensual and urbane building immediately recognised as a masterpiece, so successfully that Le Corbusier tried to claim it as his own: he doctored photographs and copied drawings sent to him by Costa after the construction. While recognisably a Purist building, the concepts which made Niemeyer's work distinct from Le Corbusier's may be seen to have emerged here: the dynamic relationship of the forms to the urban space, the sensuousness of colour, the inhabitation of the ground space.

This story was repeated at the United Nations, New York in 1947. Harrison had been impressed by his and Costa's Brazilian Pavilion at the New York World's Fair 1939, and invited him to join the rather mixed bag of consultants. Niemeyer provided the architectonic solution (model '32') to Harrison's preferred Modern aesthetic; the Beaux-Arts trained Harrison had no feeling for Modernism and of course later abandoned it for a monumental and authoritarian style. Le Corbusier had long abandoned his Purist style and would have preferred something like Chandigarh; sensing the battle lost, he fiddled with Niemeyer's proposal to produce the unsatisfactory final solution (model '32-23').

Niemeyer encountered no such interference in Brazil, however. Gustavo Capanema, who commissioned the Ministry of Education, and Juscelino Kubitschek were deeply cultured and genuinely passionate about architecture. They were also ruthless technocrats, another factor which led Le Corbusier to believe that Brazil was an ideal country for Modernism. He became almost the court architect, as Kubitschek, who commissioned Pampulha in 1940 as Mayor of Belo Horizonte, went on to commission Brasilia in 1957 as President of Brazil. Here, Niemeyer was able to repay his debt to Costa: he certainly recognised his hand in the 5 small pieces of paper submitted for the competition for the urban plan.

Niemeyer relates that Kubitschek became convinced that Brasília was feasible one night in his house in Canoas. It is possible, even probable, that Niemeyer then rushed around to Juca's Bar in Copacabana, collected half-a-dozen friends and the barman, drove 1000 km into the interior, only stopping to buy a lorry-load of wood and hire a cook, and built the Catetinho Palace with their own hands. When Kubitschek dropped by in the presidential helicopter and found a little Niemeyer house, ready with cook and butler, how could he resist?

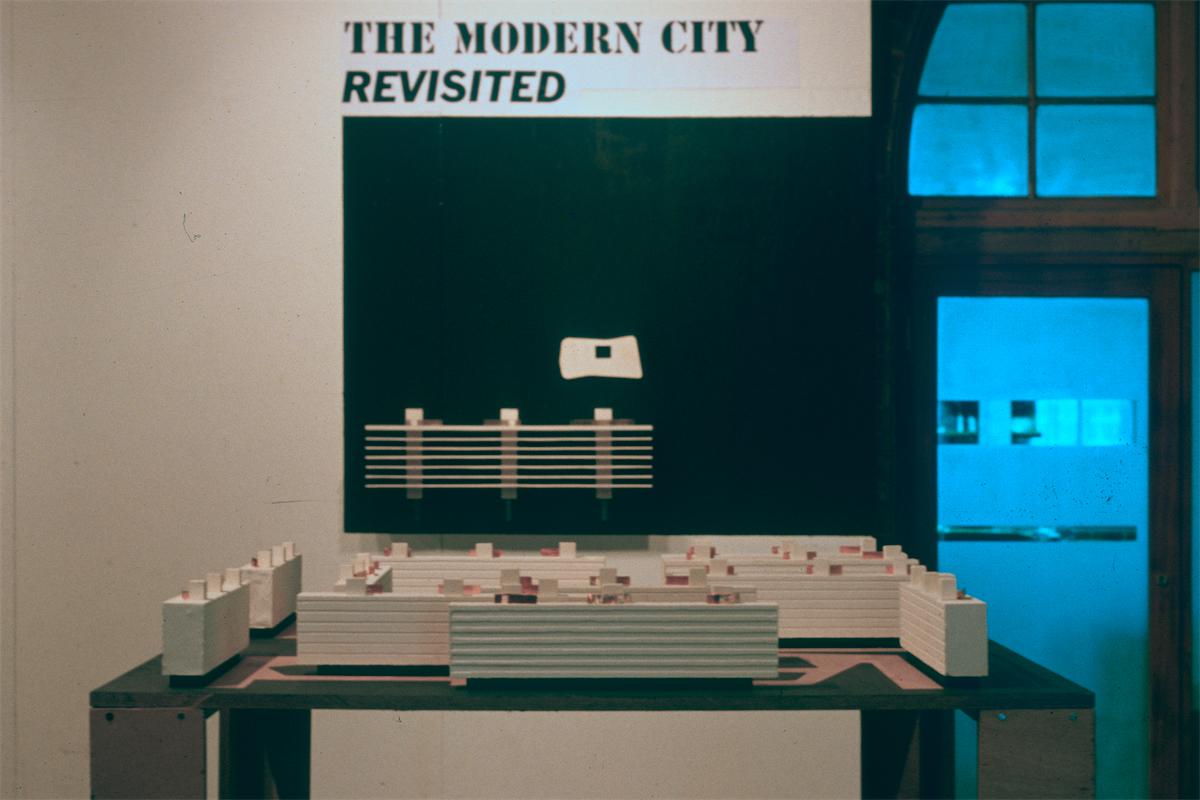

It becomes easier to understand the design of Brasília reading of the extraordinary trips across the totally unpopulated cerrado into the unknown interior of Brazil - 20 hours or more by car across dirt roads. The site was a desert of dry red silt - Costa, Niemeyer and Burle Marx made a desert bloom. Why should it be like a normal city? Why not try to redeem the Modern covenant with landscape which had been so disastrously grafted onto urban fabrics elsewhere?

The uncritical adhesion to Modernism was, of course, ultimately Niemeyer's - and Brazil's - undoing. The unresolved internal political conflicts of Brazil brought about its downfall in a CIA-backed coup in 1964. Unlike so many Modern architects who paid lip-service to political principles, Niemeyer was a genuine Communist. His communism was expressed as a commitment to public service, fully in keeping with the technocratic ideals of his contemporaries. On the succession of the military government, Niemeyer went in to a long and necessary exile. He was fortunate to extend his career in France - the Communist Party Headquarters, Paris (1965), the Cultural Centre in Le Havre (1972), Italy - the Mondadori Headquarters, Milan (1968), and Algeria - the University of Constantine (1969). The military government was deposed in 1985, but the technocratic and meritocratic regime in Brazil which had supported Niemeyer had long disappeared. His latest work is a bit of an embarrassment: compare the Latin America Centre in São Paulo (1987) to the Praça do Três Poderes in Brasília (1960) or the Museum of Contemporary Art in Niterói (1997) to the project for the Museum in Caracas (1954).

The reader need not look into The Curves of Time for any reflections on the demise of Modernism or any explanations of his career. It is almost exclusively about his clients, friends, lovers, the beauties of Rio de Janeiro and the landscape of Brazil. In typically Brazilian fashion, saudades - the sense of fleeting happiness and past joy - permeates the book. Perhaps it is these, after all, which are the most important things for an aged architect to reflect on. It may not matter that most readers will not know the personalities or the history: the true subject of the book lies in the realm of the senses.

thomas

deckker

architect