W3, Brasilia 1960s

Archive Photograph

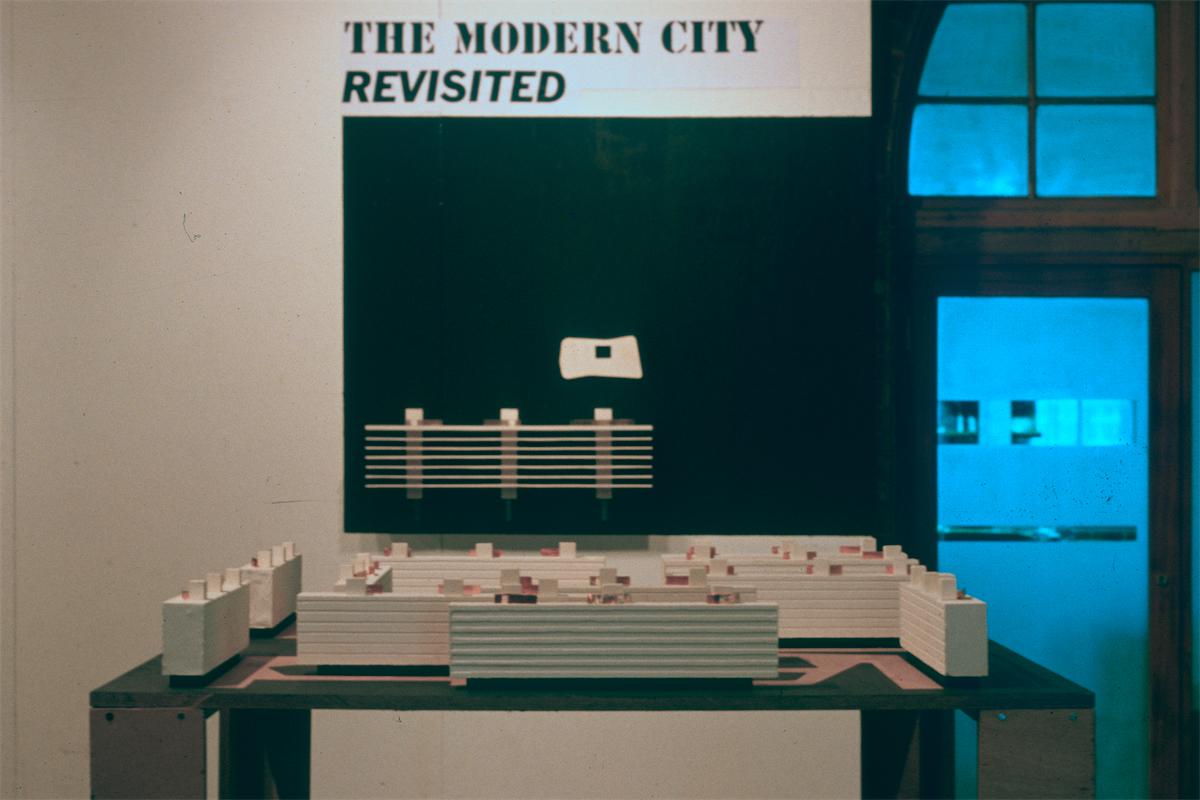

Canberra / Brasília

Canberra Contemporary Art Space [Canberra: CASC 2001]

It is difficult to disentangle fact from fiction in most things, and especially so in case of cities. The various fictions that are usually attached to Brasília - of the super-Modern city springing up overnight in the rain forest, of the cold and inhuman city with no corners, have little more than a grain of truth. How much more compelling are the fictions of life in Rio, of the life of 'luxury and pleasure' on the beaches.

It was, paradoxically, these thoughts that were in the minds of those planning Brasília in 1957. In 1930 a new President, Getúlio Vargas, had seized power, determined to throw off the agricultural economy and oligarchic political structure and Modernise the country. Initially, Rio was to be the showpiece of that Modernisation. Lucio Costa, Oscar Niemeyer and Roberto Burle Marx became the key figures in urbanism, architecture and landscape in Brazil; they had received international acclaim with their first building, the Ministry of Education in Rio (1935-42), considered to be the first regional variation of European Modernism. Niemeyer went on to design the garden suburb of Pampulha for the Mayor of Belo Horizonte, Juscelino Kubitschek, in 1940. When Kubitschek became President of Brazil in 1957, they came together again for what was to become the swansong of Brazilian Modernism: the city of Brasília.

In the 1950s, Rio was suffering terrible congestion. The city had grown along a narrow strip between the mountains and the sea, except for the low-lying and marshy areas of the port and industrial zone in the north. The Federal buildings were distributed haphazardly in an urban fabric of wildly mixed ages and conditions. Areas such as Copacabana, the prime residential district, had a density of approximately 260 persons per hectare in 1960, which was considered excessive. The government wanted an efficient centre of administration for a country widely predicted to become a regional superpower, distant from the life of 'luxury and pleasure' on the beaches.

In many respects, on the other hand, the 1950s was a 'golden age' in Rio. Niemeyer's spectacular house in Canoas (1953), a mountain-side overlooking Rio, Burle Marx's lyrical designs for the aterro (1952-c.1964), infill along the beaches into the Bay of Guanabara and the lagoon, and Costa's highly-regarded Parque Guinle (1948-54), the first Modern apartment blocks in Rio, convinced many that Rio was the centre of a tropical 'free-form' Modernism. Costa, Niemeyer and Burle Marx extended their experiences in Rio directly into the design of the new Capital.

Brasília became the swansong of Brazilian Modernism for one simple reason: Kubitschek's successor João Goulart was deposed by a CIA-backed military coup in 1964. The ditadura [dictatorship] was catastrophic for Brazil, although it never sank to the depths of Chile and Argentina, with isolation and repression in all areas of life. After the ditadura was overturned by a civilian government in 1984, Brazil adopted a North American consumer society with a vengeance.

Rodoviaria, Brasilia 1960s

Archive Photograph

The competition for the city of Brasília won by Costa in 1957 - on five small pieces of paper with hand-written notes and hand-drawn sketches - seemed to embody the still fruitful ideal of European Modernism. The Costa plan was chosen because it was not really functional (all the competition entries were based on the separation of functions of the 'Charte d'Athène': dwelling, work, leisure, and circulation): it was chosen, above all, because its symbolism captured the Modernising ideals of Kubitschek's administration. Kubitschek appointed Niemeyer as architect for the public buildings, and Costa brought in Burle Marx to design the landscaping.

At first glance, Costa's plan seemed only to embody the urban ideals of European Modernism, but in reality it was influenced by a wide range of experiences. Costa had made a last-minute submission for the competition because he had been teaching at the Parsons School of Design in New York. He later cited among his influences his memories of Paris and of the lawns of English country houses from his childhood, Brazilian Colonial towns, ancient Chinese irrigation works, and the Parkways he had just seen around the city of New York.

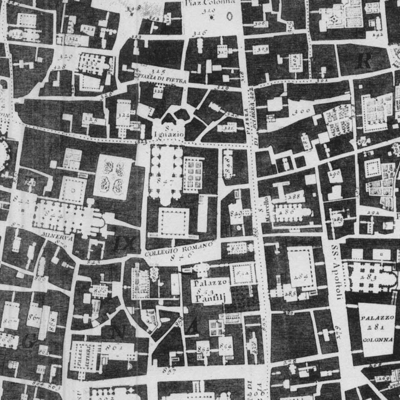

It was typical of Costa's utopian vision that the city would be planned for a mixture of classes. The middle class were to inhabit self-contained squares of apartment blocks called superquadras; comércios [local shopping streets], with the all-important bakeries, were projected for one side of each superquadra and local cultural and leisure facilities - churches, cinemas, schools, libraries and sports centres - on the other, intended to provide a complete way of life for the Modern brasileiro. A zone of low-income terrace housing, the Setor de Habitações Individuais Germinadas, was planned along the service road, the W3. Ministers and other important politicians were to occupy a small area of detached houses adjacent to the lake. The city was intended to be complete; there was no provision for expansion.

The design of the external space in each superquadra, and the relationship of the apartments to it, reinforced the sense of public space, despite the blocks being nominally free-standing. In an archetypal original superquadra, apartment blocks were paired closely around car parking areas, leaving the remaining landscape space quite open and freely arranged. This hierarchy continued into the plan of the apartments: the social spaces - living rooms and bedrooms - faced the gardens, while the kitchens and service areas faced the car parking areas. Surprisingly, the interior arrangements vary widely, from single-bedroom apartments to luxurious four-bedroom apartments with a dependência completa [complete servant's quarters] within the same building envelope. An important feature was the suppression of the autonomy of the block, especially the omission of balconies; Costa compared this to Haussmann's garabit for Paris.

Congresso, Brasilia 1960s

Archive Photograph

The construction of Brasília was the most extraordinary adventure. The site was an immense desert lost in the planalto [central plateau]. The only access was by dirt roads 600 km from Belo Horizonte. Niemeyer, an ardent Communist, lived in one of several temporary encampments which had been built to house the candangos, the construction workers (as they could not live on the construction site itself). No-one involved confused the camaraderie of the 'Cidade Livre', the main candango encampment, with their intentions for the new Capital; they wanted to create a city that symbolised the Modernity of the country. Initially, at least, the city was widely acknowledged as a successful representation of the importance of Brazil. Contemporary pictures are neither propaganda nor exaggeration: it was a genuinely popular utopia. So rapid was the descent of Brasília into ignominy that it is tempting to see the Pilot Plan as inherently flawed, but this is certainly not the complete explanation. The most immediate problem was that the inhabitants - not only the candangos, but also the civil servants - were drawn from the poorest and least-developed parts of Brazil - the interior and north-east. For these people, Brasília was a dream come true - apartments were virtually given away to encourage people to move there. It also meant jobs; no civil servant lost their job in Rio: the bureaucracy simply increased in number.

Whatever the defects of the Pilot Plan may have been, however, the current condition of Brasília owes little to them. In 1964, although most of the government buildings were complete, only 10 of the projected 92 main superquadras had a significant amount of construction, all except one in the asa sul [south wing]. Of these, only 6, known in Brasília as the superquadras originais [original superquadras], contained the original public facilities and landscaping designed by Niemeyer and Burle Marx. After 1964, buildings increasingly diverged from the spirit and letter of the Pilot Plan. Against Costa's intentions, whole superquadras as well as individual blocks were sold to developers, initially in an attempt to speed up construction, which opened the development of the city to more populist pressures. Today, only two or three superquadras sites remain undeveloped.

Palácio da Alvorada, Brasilia 1960s

Archive Photograph

The current development of the city, in essence a populist reaction to the unfinished Pilot Plan, is unfortunately more anonymous and hostile than the Modern it replaces. The accelerating 'post-modernisation' of even the original blocks - the application of 'Colonial' decorative features - is destroying the integrity of architecture and landscape. The new blocks and superquadras in the asa norte [north wing], the most recent to be developed, have neither dignified interior spaces nor public exterior space. The original zone of low-income terrace housing in the W3 adjacent to the superquadras originais have now all been transformed into middle-class 'casas do interior' [country-style houses]. The new commercial buildings in the central Setores Comerciais [Commercial Zones] - offices, apart-hotels and shopping malls - are isolated in the middle of enormous car parks, without any pedestrian access or landscaping. Those able to afford to do so prefer the areas of detached houses around the lake - the Lago Sul [South Lake] and Lago Norte [North Lake] - which formed part of the Pilot Plan but which have now far exceeded their intended size. These houses are virtually a satire on architecture: the main design inspiration comes from the fantastically exaggerated fictions of the lives of the super-rich in São Paulo to be seen in the novelas [soap operas]. What has emerged since the original plan, and was in no way predicted or desired, was the dominance of the cidades satélites [satellite cities]. Out of a total population of two million in the Distrito Federal, only 250,000 live in Brasília; 1,750,000, seven times the planned population, live in the satellite cities. Although the common and widely-propagated image is of garbage dumps, the term 'satellite city' actually covers a wide variety of types. Taguatinga, an original satellite city, far exceeds the Pilot Plan in population and has substantial middle-class districts; the Cidade Livre, renamed Núcleo Bandeirante [Pioneer Settlement] in 1961, has become a well-established middle-class suburb. Recanto das Emas, further out in the Distrito Federal (with a journey time of one hour by bus to Brasília), is inhabited by poorer people, and Valparaiso, outside the Distrito Federal in the state of Goiás (with a journey time of at least one-and-a-half hours by bus to Brasília), by the even poorer.

The inhabitants of the Distrito Federal now prefer the shopping malls with cinema complexes and 'fast-food' outlets, a simulacrum of urban life, which has caused great prejudice to the central Setor de Diversões [Shopping and Entertainment Centre] and the comércios. Brasília has very few restaurants and bars, even fewer good ones. It is not just the quality of food or ambience, however, but also the place these have in urban life which is important: a loophole in planning regulations, for example, allows petrol stations to set up bars, with predictable results. The planning apparatus is totally inimical to the city, and only rare initiatives have respected the intentions of the Pilot Plan. The result is that not only is the city virtually impenetrable for outsiders but the urban nature of the city is hardly apparent to the inhabitants themselves.

Catedral, Brasilia 1960s

Archive Photograph

The failure of a pubic realm to emerge from the Pilot Plan cannot be blamed totally on consumerist paranoia, however. The technocratic ideal of Modern planning - the planned separation of functions set in a landscape - was inimical to the formation of public life. However utopian the superquadras originais appear compared to the later developments - today they are by far the most successful superquadras - it is true that the Pilot Plan did not encourage people to meet and enjoy the public realm. The recovery of urban centres - especially those of Modern planning, whether in Brazil or abroad - has been through a democratic mixture of uses and interpretations of use: rich and poor, casual and formal, private and public.

Brasília, in the final analysis, appears as a model of sanity among contemporary populist developments in Brazil, and urban compared to contemporary suburban 'new towns' elsewhere. Modernism, without any doubt, was the cultural high point in recent history in Brazil; the conception of the Modern brasileiro was dignified and even beautiful. There is no reason to assume that the present binge of consumerism will continue. It may be readily acknowledged that Brasília is not a model for urban planning in the future, but as an urban plan of the recent past it is almost viable. How to accommodate spaces of mixed use and interpretations of use within its fabric is the major question facing Brasília today.

Thomas Deckker

London 2001