thomas

deckker

architect

Talks at Veretec

2022-23

2022-23

BBC: The Inquiry

BBC World Service 2019

BBC World Service 2019

Brasilia: Life Beyond Utopia

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2016

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2016

Brasilia: Life Beyond Utopia

Architectural Design [April 2016]

Architectural Design [April 2016]

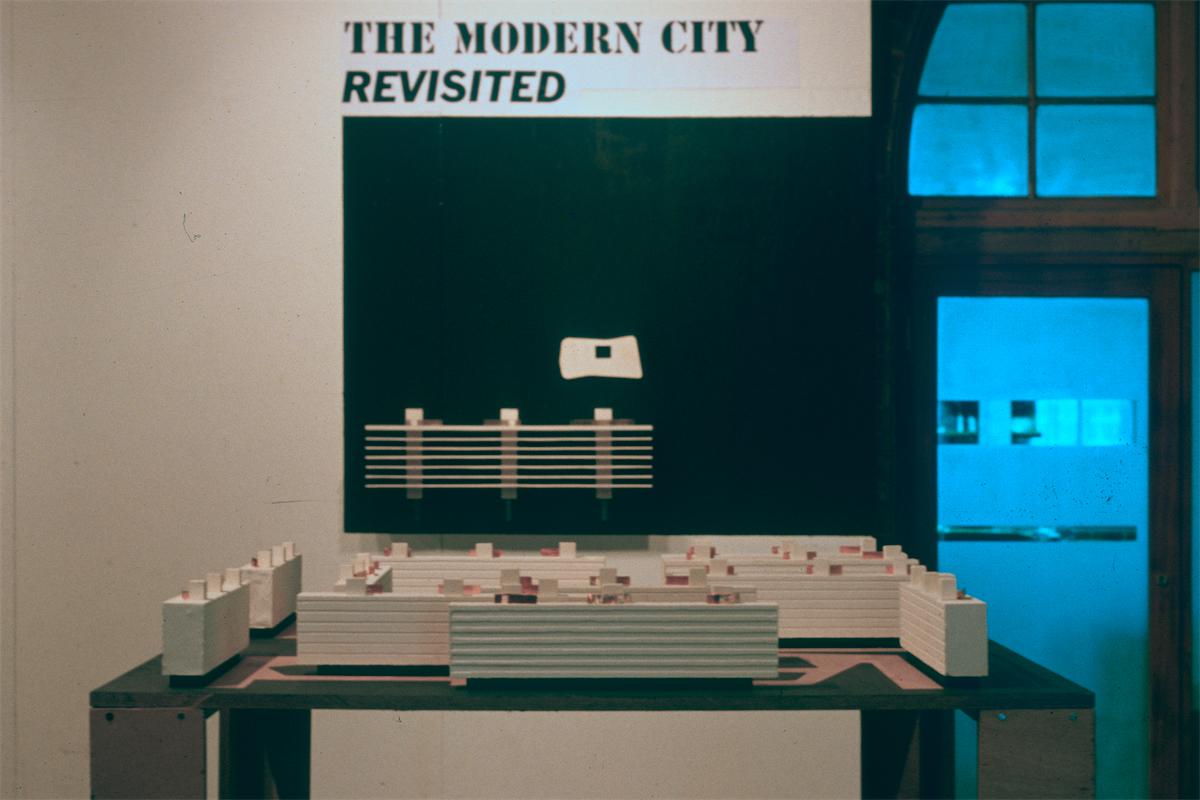

Two exhibitions for the McAslan Gallery

McAslan Gallery 2016

McAslan Gallery 2016

Edzell Castle: Architectural Treatises in Late 16th Century Scotland

Garden History Society 2014

Garden History Society 2014

Architecture and the Humanities

Architectural Research Quarterly 2014

Architectural Research Quarterly 2014

Urban Planning in Rio 1870-1930: the Construction of Modernity

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2014

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2014

Review of Remaking London: Design and Regeneration in Urban Culture

Architectural Research Quarterly 2013

Architectural Research Quarterly 2013

Life's a Beach: Oscar Niemeyer, Landscape and Women

The Rest is Noise Festival

South Bank, London 6 October 2013

The Rest is Noise Festival

South Bank, London 6 October 2013

BBC: Last Word

BBC Radio 4 7 & 9 December 2012

BBC Radio 4 7 & 9 December 2012

Brasilia: Fictions and Illusions

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2012

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2012

Connected Communities Symposium

University of Dundee 2011

University of Dundee 2011

Architecture + ESI: an architect's perspective

FESI [The UK Forum for Engineering Structural Integrity] 2011

FESI [The UK Forum for Engineering Structural Integrity] 2011

Review of Mapping London

Architectural Research Quarterly 2010

Architectural Research Quarterly 2010

The Studio of Antonio Carlos Elias

Epulis Fissuratum [Brasilia 2006]

Epulis Fissuratum [Brasilia 2006]

Urban Entropies: A Tale of Three Cities

Architectural Design [September 2003]

Architectural Design [September 2003]

New Architecture in Brazil

- Photographs by Michael Frantzis

Brazilian Embassy, London

5-6 March 2003

- Photographs by Michael Frantzis

Brazilian Embassy, London

5-6 March 2003

Natural Spirit (Places to Live 007)

Wallpaper* [January/February 2003]

Wallpaper* [January/February 2003]

Architects Directory

Wallpaper* [July/August 2002]

Wallpaper* [July/August 2002]

Foreign Legion

RIBA Journal [March 2002]

RIBA Journal [March 2002]

Architects and Technology

The Encyclopaedia of Architectural Technology [London: Wiley 2002]

The Encyclopaedia of Architectural Technology [London: Wiley 2002]

- Alvar Aalto

- Le Corbusier

- Louis Kahn

- Richard Neutra

- Oscar Niemeyer

- Renzo Piano

- Alvaro Siza

Mexican-American Architecture

Mexican-American Encyclopaedia [2002]

Mexican-American Encyclopaedia [2002]

In the Realm of the Senses

Architectural Design [July 2001]

Architectural Design [July 2001]

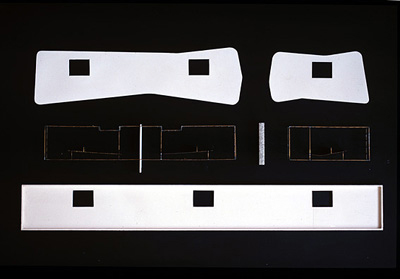

Thomas Deckker: Two Projects in Brasilia

Architectural Design [Oct 2000]

Architectural Design [Oct 2000]

First International Seminar on the Teaching of the Built Environment [SIEPAC]

University of Sao Paulo, Brazil

13-15 Sept 2000

University of Sao Paulo, Brazil

13-15 Sept 2000

Issues in Architecture Art & Design

vol. 6 no. 1 [University of East London 2000]

vol. 6 no. 1 [University of East London 2000]

Monte Carasso: The re-invention of the site

Issues in Architecture Art & Design vol. 5 no. 2 [University of East London 1998]

Issues in Architecture Art & Design vol. 5 no. 2 [University of East London 1998]

Specific Objects / Specific Sites

Rethinking the Architecture / Landscape Relationship, University of East London,

26-28 Mar 1996

Rethinking the Architecture / Landscape Relationship, University of East London,

26-28 Mar 1996

Herzog & deMeuron

Issues in Architecture Art & Design vol. 3 no. 2 [University of East London 1994]

Issues in Architecture Art & Design vol. 3 no. 2 [University of East London 1994]

Oscar Niemeyer: Congresso Nacional Brasilia

photograph © Thomas Deckker 1997

photograph © Thomas Deckker 1997

Architects and Technology Index

The Encyclopaedia of Architectural Technology [London: Wiley 2002]

Oscar Niemeyer

Oscar Niemeyer (b. 1907) was born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and grew up at a time when Brazil was determined to 'Modernise' and throw off its rural and agrarian past. Niemeyer was fortunate to be part of a brilliant circle of 'Modern' architects, engineers, and not least, clients; Gustavo Capanema, the Minister who commissioned the Ministry of Education building in 1935, and Juscelino Kubitschek, who commissioned Pampulha in 1940 as Mayor of Belo Horizonte and went on to commission Bras'lia in 1957 as President of Brazil, were deeply cultured and genuinely passionate about architecture.

Two factors made European Modernism fruitful in Brazil: the advanced state of concrete construction and the otherwise primitive state of the building industry. There were no steel mills in Brazil before 1943; structural steel, and the technical supervision of the construction, had to be imported from the United States. Reinforced concrete had the advantages of being prepared on site and of not requiring specialised labour. As workmen were illiterate, no working drawings need be prepared; the use of a good engineer, however, was vital to design an appropriate concrete frame, and very simple detailing was essential as the integration of components could not be anticipated. Virtually all fittings and finishing materials had to be imported from the United States, which not only resulted in high initial costs but made maintenance an almost insuperable problem.

A protégé of Lucio Costa (1902-1998), Niemeyer did not initially show any evidence of his extraordinary abilities. He learnt all he needed to know about the Modern architectural language in a few weeks in August 1936 during Le Corbusier's brief visit to Brazil as adviser on the Ministry of Education building. It was Niemeyer, however, who must take the credit for turning Costa's rather naive initial proposal and Le CorbusierÕs clumsy sketches into the final building. It was the first tall Modern Movement building, and utilised pilotis of several sizes and spacings to give a dynamic rhythm to the form. Horizontally-pivoting brise-soleils - in bright blue asbestos cement - were used for the first time. The engineer was Emilio Baumgart (1888-1942), who had set the world record height for concrete construction with the A Noite building, Rio de Janeiro (1928).

Niemeyer did not feel he had achieved maturity until the more free-form buildings in Pampulha (1940-43) such as the Casino, the Casa de Baile, the Yacht Club and the Church of Sao Francisco which was his first use of shell vaults. Niemeyer continued to build extensively in Belo Horizonte and the state of Minas Gerais under the patronage of Kubitschek, and began to acquire an international reputation, being a consultant on the United Nations building, New York (1947) and building an apartment block at the Interbau exhibition, Berlin (1957). Some projects of this period, such as the Museum in Caracas (1954), an inverted pyramid, were extraordinarily powerful, but after 1957 all his energy was concentrated on Bras'lia.

The main Government buildings in Brasilia all employ some form of deep-plan concrete construction with light perimeter columns. He was fortunate to collaborate with another brilliant concrete engineer, Joaquim Cardoso (1897-1978); the twin-domed Congresso Nacional (1957-60) was virtually a monolithic concrete shell. The rectilinear Ministries, however, were steel-framed and clad in heat-absorbing glass, which did not function well and led to a rash of wall-mounted air-conditioning units. Perhaps surprisingly, however, Niemeyer's Palaces in Brasilia are comfortable. The high ratio of heavy roof construction to building volume (necessitated by the long spans and deep plans), the wide overhangs, the provision for cross-ventilation in the glazed walls and the landscaping mean that internal temperatures are moderate. In the Alvorado Palace (1957), for instance, only the library is air-conditioned. In his apartment blocks in the residential quarters, the use of cambogo (pierced masonry screens), bandeiras (louvred timber screens) and brise-soleils mean that environmental conditions in these shallow-plan and poorly-built apartments are actually reasonable.

Despite the programme of modernisation in Brazil, a considerable amount of the structural steel and finishing materials in Brasilia had to be imported from the United States. This, and cost of developing the city, led to the cessation of building activity in 1960 when only the main Government buildings and about 10% of the apartment buildings had been built. The military coup in 1964 quickly led to Niemeyer's exile. Niemeyer was fortunate to extend his career in France - the Communist Party Headquarters, Paris (1967-80), the Cultural Centre in Le Havre (1972-83), Italy - the Mondadori Headquarters, Milan (1968-75), and Algeria - the University of Constantine (1969-72). He collaborated with Jean Prouvé on the Communist Party Headquarters, which doubtless made the curtain wall more acceptable in the more rigorous climate of Paris. Although this building sensuously exploits its corner site in the 19th-century Parisian garabit, later buildings became more formal exercises in concrete construction.

After his return to Brazil following the fall of the military dictatorship in 1984, Niemeyer modified many of his buildings to solve outstanding environmental problems. The addition of brise-soleils to the Palaces and Ministries in Brasilia has not reduced their architectural power. In his latest works, such as the Latin America Centre, Sao Paulo (1987) and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Niterói (1997) Niemeyer has exploited the plastic nature of concrete without, however, matching the spatial and material sensuousness which marked his earlier work.

Two factors made European Modernism fruitful in Brazil: the advanced state of concrete construction and the otherwise primitive state of the building industry. There were no steel mills in Brazil before 1943; structural steel, and the technical supervision of the construction, had to be imported from the United States. Reinforced concrete had the advantages of being prepared on site and of not requiring specialised labour. As workmen were illiterate, no working drawings need be prepared; the use of a good engineer, however, was vital to design an appropriate concrete frame, and very simple detailing was essential as the integration of components could not be anticipated. Virtually all fittings and finishing materials had to be imported from the United States, which not only resulted in high initial costs but made maintenance an almost insuperable problem.

A protégé of Lucio Costa (1902-1998), Niemeyer did not initially show any evidence of his extraordinary abilities. He learnt all he needed to know about the Modern architectural language in a few weeks in August 1936 during Le Corbusier's brief visit to Brazil as adviser on the Ministry of Education building. It was Niemeyer, however, who must take the credit for turning Costa's rather naive initial proposal and Le CorbusierÕs clumsy sketches into the final building. It was the first tall Modern Movement building, and utilised pilotis of several sizes and spacings to give a dynamic rhythm to the form. Horizontally-pivoting brise-soleils - in bright blue asbestos cement - were used for the first time. The engineer was Emilio Baumgart (1888-1942), who had set the world record height for concrete construction with the A Noite building, Rio de Janeiro (1928).

Niemeyer did not feel he had achieved maturity until the more free-form buildings in Pampulha (1940-43) such as the Casino, the Casa de Baile, the Yacht Club and the Church of Sao Francisco which was his first use of shell vaults. Niemeyer continued to build extensively in Belo Horizonte and the state of Minas Gerais under the patronage of Kubitschek, and began to acquire an international reputation, being a consultant on the United Nations building, New York (1947) and building an apartment block at the Interbau exhibition, Berlin (1957). Some projects of this period, such as the Museum in Caracas (1954), an inverted pyramid, were extraordinarily powerful, but after 1957 all his energy was concentrated on Bras'lia.

The main Government buildings in Brasilia all employ some form of deep-plan concrete construction with light perimeter columns. He was fortunate to collaborate with another brilliant concrete engineer, Joaquim Cardoso (1897-1978); the twin-domed Congresso Nacional (1957-60) was virtually a monolithic concrete shell. The rectilinear Ministries, however, were steel-framed and clad in heat-absorbing glass, which did not function well and led to a rash of wall-mounted air-conditioning units. Perhaps surprisingly, however, Niemeyer's Palaces in Brasilia are comfortable. The high ratio of heavy roof construction to building volume (necessitated by the long spans and deep plans), the wide overhangs, the provision for cross-ventilation in the glazed walls and the landscaping mean that internal temperatures are moderate. In the Alvorado Palace (1957), for instance, only the library is air-conditioned. In his apartment blocks in the residential quarters, the use of cambogo (pierced masonry screens), bandeiras (louvred timber screens) and brise-soleils mean that environmental conditions in these shallow-plan and poorly-built apartments are actually reasonable.

Despite the programme of modernisation in Brazil, a considerable amount of the structural steel and finishing materials in Brasilia had to be imported from the United States. This, and cost of developing the city, led to the cessation of building activity in 1960 when only the main Government buildings and about 10% of the apartment buildings had been built. The military coup in 1964 quickly led to Niemeyer's exile. Niemeyer was fortunate to extend his career in France - the Communist Party Headquarters, Paris (1967-80), the Cultural Centre in Le Havre (1972-83), Italy - the Mondadori Headquarters, Milan (1968-75), and Algeria - the University of Constantine (1969-72). He collaborated with Jean Prouvé on the Communist Party Headquarters, which doubtless made the curtain wall more acceptable in the more rigorous climate of Paris. Although this building sensuously exploits its corner site in the 19th-century Parisian garabit, later buildings became more formal exercises in concrete construction.

After his return to Brazil following the fall of the military dictatorship in 1984, Niemeyer modified many of his buildings to solve outstanding environmental problems. The addition of brise-soleils to the Palaces and Ministries in Brasilia has not reduced their architectural power. In his latest works, such as the Latin America Centre, Sao Paulo (1987) and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Niterói (1997) Niemeyer has exploited the plastic nature of concrete without, however, matching the spatial and material sensuousness which marked his earlier work.

Thomas Deckker

London 2001

London 2001