thomas

deckker

architect

Talks at Veretec

2022-23

2022-23

BBC: The Inquiry

BBC World Service 2019

BBC World Service 2019

Brasilia: Life Beyond Utopia

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2016

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2016

Brasilia: Life Beyond Utopia

Architectural Design [April 2016]

Architectural Design [April 2016]

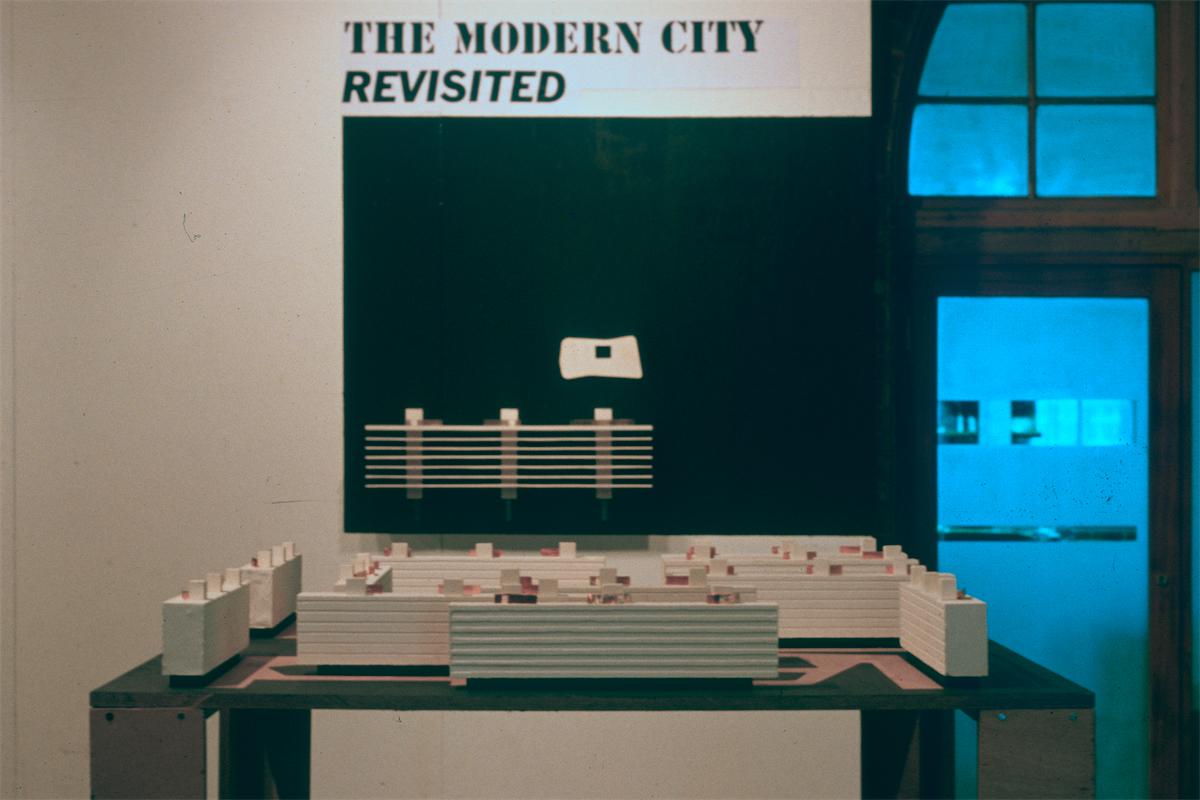

Two exhibitions for the McAslan Gallery

McAslan Gallery 2016

McAslan Gallery 2016

Edzell Castle: Architectural Treatises in Late 16th Century Scotland

Garden History Society 2014

Garden History Society 2014

Architecture and the Humanities

Architectural Research Quarterly 2014

Architectural Research Quarterly 2014

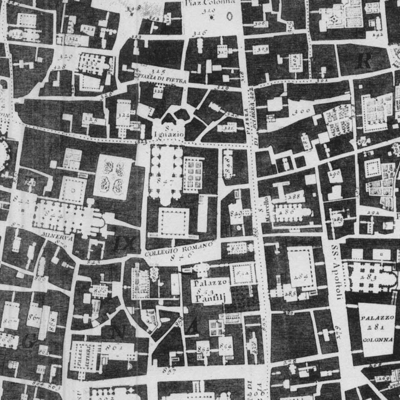

Urban Planning in Rio 1870-1930: the Construction of Modernity

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2014

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2014

Review of Remaking London: Design and Regeneration in Urban Culture

Architectural Research Quarterly 2013

Architectural Research Quarterly 2013

Life's a Beach: Oscar Niemeyer, Landscape and Women

The Rest is Noise Festival

South Bank, London 6 October 2013

The Rest is Noise Festival

South Bank, London 6 October 2013

BBC: Last Word

BBC Radio 4 7 & 9 December 2012

BBC Radio 4 7 & 9 December 2012

Brasilia: Fictions and Illusions

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2012

Brazil Institute, Kings College London 2012

Connected Communities Symposium

University of Dundee 2011

University of Dundee 2011

Architecture + ESI: an architect's perspective

FESI [The UK Forum for Engineering Structural Integrity] 2011

FESI [The UK Forum for Engineering Structural Integrity] 2011

Review of Mapping London

Architectural Research Quarterly 2010

Architectural Research Quarterly 2010

The Studio of Antonio Carlos Elias

Epulis Fissuratum [Brasilia 2006]

Epulis Fissuratum [Brasilia 2006]

Urban Entropies: A Tale of Three Cities

Architectural Design [September 2003]

Architectural Design [September 2003]

New Architecture in Brazil

- Photographs by Michael Frantzis

Brazilian Embassy, London

5-6 March 2003

- Photographs by Michael Frantzis

Brazilian Embassy, London

5-6 March 2003

Natural Spirit (Places to Live 007)

Wallpaper* [January/February 2003]

Wallpaper* [January/February 2003]

Architects Directory

Wallpaper* [July/August 2002]

Wallpaper* [July/August 2002]

Foreign Legion

RIBA Journal [March 2002]

RIBA Journal [March 2002]

Architects and Technology

The Encyclopaedia of Architectural Technology [London: Wiley 2002]

The Encyclopaedia of Architectural Technology [London: Wiley 2002]

- Alvar Aalto

- Le Corbusier

- Louis Kahn

- Richard Neutra

- Oscar Niemeyer

- Renzo Piano

- Alvaro Siza

Mexican-American Architecture

Mexican-American Encyclopaedia [2002]

Mexican-American Encyclopaedia [2002]

In the Realm of the Senses

Architectural Design [July 2001]

Architectural Design [July 2001]

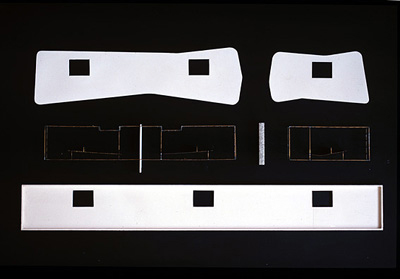

Thomas Deckker: Two Projects in Brasilia

Architectural Design [Oct 2000]

Architectural Design [Oct 2000]

First International Seminar on the Teaching of the Built Environment [SIEPAC]

University of Sao Paulo, Brazil

13-15 Sept 2000

University of Sao Paulo, Brazil

13-15 Sept 2000

Issues in Architecture Art & Design

vol. 6 no. 1 [University of East London 2000]

vol. 6 no. 1 [University of East London 2000]

Monte Carasso: The re-invention of the site

Issues in Architecture Art & Design vol. 5 no. 2 [University of East London 1998]

Issues in Architecture Art & Design vol. 5 no. 2 [University of East London 1998]

Specific Objects / Specific Sites

Rethinking the Architecture / Landscape Relationship, University of East London,

26-28 Mar 1996

Rethinking the Architecture / Landscape Relationship, University of East London,

26-28 Mar 1996

Herzog & deMeuron

Issues in Architecture Art & Design vol. 3 no. 2 [University of East London 1994]

Issues in Architecture Art & Design vol. 3 no. 2 [University of East London 1994]

Le Corbusier: Maison Jaoul, Paris

photograph © Thomas Deckker 1982

photograph © Thomas Deckker 1982

Architects and Technology Index

The Encyclopaedia of Architectural Technology [London: Wiley 2002]

Le Corbusier

Le Corbusier (1887-1965) was as unceasingly innovative with technology as he was in any other field of his endeavours, and with equally controversial results. He came to prominence in architecture in the 1920s in part by abstracting and promoting particular aspects of current architectural practice not as pragmatic constructional solutions but as abstract and ideal forms of an industrial and technocratic society.

Le Corbusier's architectural forms were facilitated by both constructional and environmental innovations. The 'plan libre' was dependent on a system of flat concrete slabs and cylindrical 'pilotis'; this had been initially proposed in 1914 as the 'Dom-ino' system and appeared in projects for the Citrohan House (1920/22), a pun on the car manufacturer Citroën, with whose director, André Citroën, Le Corbusier felt an entirely un-reciprocated affinity. The 'mur neutralisant' (neutralising wall) and 'respiration exact' (exact ventilation) was a form of air conditioning by passing heated and cooled air inside a curtain wall, supplemented by internal ventilation. So convincing was Le Corbusier in promoting these that many came to believe that he had, in fact, invented air conditioning.

Despite his ceaseless self-promotion, Le Corbusier did not pursue his own innovations as normative solutions but as a field for further invention, such as, for example, the 'four house types' which utilised the 'plan libre' in different ways. It is apparent, however, that he had little grasp of basic engineering principles. In the Villa Savoye (1928-31), for example, the circular pilotis were compromised by square columns and beams (such as at the main entrance), although these compromises served to enrich the architectural experience. In all the works of this period, Le Corbusier struggled with basic environmental control, as he reduced the construction to the point at which thermal and acoustic performance, and even weatherproofing, was completely inadequate. The 'mur neutralisant', which he promoted as appropriate for the North Pole and the tropics, met with firm rejection in Moscow in 1929 and Rio de Janeiro in 1936. It was flawed theoretically and discredited in tests carried out for the Centrosoyuz Building, Moscow (1929-33). He did use the simpler 'pan-de-verre' (fixed curtain wall) in the Armée du Salut (1929-32) and the Pavillon Suisse (1930-32) in Paris, with disastrous results.

Le Corbusier's trips to Spain and South America in 1929 marked a turning point in his work; where exactly is not clear because a sketch of Catalan vaults - possibly derived from Gaud' - which was to be influential on his later work is found in the sketchbooks made during his South American journey. In any case, the experience of flying in Argentina and the sensuousness of life in Brazil marked a change in direction. His trip to New York in 1935 - his first to the technically far superior United States - perhaps led him to reassess the reliance on mechanical services which his Ville Radieuse embodied.

In contrast to the initial Purist phase, Le Corbusier's few works in the 1930s mixed 'primitive' and industrial forms of construction. His first experiment with 'primitive' construction was for a project for the Errazuris House in Chile (1929) made of stone and unfinished timber, and stone walls appeared in the Pavillon Suisse and the apartment building in rue Nungesser-et-Coli, Paris (1933). His first complete house with exposed stone construction in cellular forms was La Tremblade, Mathes (1935), followed by the Petite Maison de Weekend, Paris (1934-35), in brick with concrete vaults.

After the Second World War, Le Corbusier abandoned the utopian and technological direction of his Purist phase almost entirely. In 1946 brise-soleils and a revised ventilation system were added to the Armée du Salut, and new glazing systems to Centrosoyuz and the Pavillon Suisse, which had been virtually uninhabitable. The Maisons Jaoul, Paris (1952-54) were built of brick with tiled vaults. Experiments in concrete construction became increasingly sophisticated; columns, walls, brise-soleils, and ondulatoires (an infill system of fixed glazing and openable ventilators in concrete frames) were combined in lyrical compositions. In the Couvent de la Tourette, Lyons (1956-59), the repetitive structure of the cells was expressed physically and symbolically in pre-cast facade units, while the public rooms were more freely articulated in-situ; in the Unité d'Habitation, Marseilles (1946-52) the substructure in beton brut is almost zoomorphic. The public buildings in Chandigarh (1950-64) were made entirely in-situ with the lowest possible technology.

The more lyrical and expressive nature of his post-war work did not exclude practical problems, however. Wallace K. Harrison wrote of his incredulity at Le Corbusier's proposal to put brise-soleils on his project for the United Nations building, New York (1947) - they would have resulted in insuperable problems with snow. Criticisms have been voiced that the brise-soleils of the Chandigarh buildings are also unsuitable for the dusty North Indian plain; furthermore, the massive concrete construction acts as a heat store as it is a single layer. Although much of the imagery of the buildings was derived from technical sources - such as the Hall of the Legislative Assembly from a power-station cooling tower - inadequate ventilation compounds the problems. On the other hand, the basic concrete construction of La Tourette has proved appropriate to the milder climate of the Rhone valley and the monastic life of its inhabitants.

In his last work, the little-known Heidi Weber Pavilion, Zurich (1962-66), Le Corbusier prefigured many aspects of the emerging 'high-tech' movement, with walls of interchangeable vitreous enamel panels and ready-made industrial fittings.

Despite his obvious technical shortcomings, the power of his imagery and the brilliance of his creativity, not least in the area of technology, mean that Le Corbusier is an architect to whom others will fruitfully return.

Le Corbusier's architectural forms were facilitated by both constructional and environmental innovations. The 'plan libre' was dependent on a system of flat concrete slabs and cylindrical 'pilotis'; this had been initially proposed in 1914 as the 'Dom-ino' system and appeared in projects for the Citrohan House (1920/22), a pun on the car manufacturer Citroën, with whose director, André Citroën, Le Corbusier felt an entirely un-reciprocated affinity. The 'mur neutralisant' (neutralising wall) and 'respiration exact' (exact ventilation) was a form of air conditioning by passing heated and cooled air inside a curtain wall, supplemented by internal ventilation. So convincing was Le Corbusier in promoting these that many came to believe that he had, in fact, invented air conditioning.

Despite his ceaseless self-promotion, Le Corbusier did not pursue his own innovations as normative solutions but as a field for further invention, such as, for example, the 'four house types' which utilised the 'plan libre' in different ways. It is apparent, however, that he had little grasp of basic engineering principles. In the Villa Savoye (1928-31), for example, the circular pilotis were compromised by square columns and beams (such as at the main entrance), although these compromises served to enrich the architectural experience. In all the works of this period, Le Corbusier struggled with basic environmental control, as he reduced the construction to the point at which thermal and acoustic performance, and even weatherproofing, was completely inadequate. The 'mur neutralisant', which he promoted as appropriate for the North Pole and the tropics, met with firm rejection in Moscow in 1929 and Rio de Janeiro in 1936. It was flawed theoretically and discredited in tests carried out for the Centrosoyuz Building, Moscow (1929-33). He did use the simpler 'pan-de-verre' (fixed curtain wall) in the Armée du Salut (1929-32) and the Pavillon Suisse (1930-32) in Paris, with disastrous results.

Le Corbusier's trips to Spain and South America in 1929 marked a turning point in his work; where exactly is not clear because a sketch of Catalan vaults - possibly derived from Gaud' - which was to be influential on his later work is found in the sketchbooks made during his South American journey. In any case, the experience of flying in Argentina and the sensuousness of life in Brazil marked a change in direction. His trip to New York in 1935 - his first to the technically far superior United States - perhaps led him to reassess the reliance on mechanical services which his Ville Radieuse embodied.

In contrast to the initial Purist phase, Le Corbusier's few works in the 1930s mixed 'primitive' and industrial forms of construction. His first experiment with 'primitive' construction was for a project for the Errazuris House in Chile (1929) made of stone and unfinished timber, and stone walls appeared in the Pavillon Suisse and the apartment building in rue Nungesser-et-Coli, Paris (1933). His first complete house with exposed stone construction in cellular forms was La Tremblade, Mathes (1935), followed by the Petite Maison de Weekend, Paris (1934-35), in brick with concrete vaults.

After the Second World War, Le Corbusier abandoned the utopian and technological direction of his Purist phase almost entirely. In 1946 brise-soleils and a revised ventilation system were added to the Armée du Salut, and new glazing systems to Centrosoyuz and the Pavillon Suisse, which had been virtually uninhabitable. The Maisons Jaoul, Paris (1952-54) were built of brick with tiled vaults. Experiments in concrete construction became increasingly sophisticated; columns, walls, brise-soleils, and ondulatoires (an infill system of fixed glazing and openable ventilators in concrete frames) were combined in lyrical compositions. In the Couvent de la Tourette, Lyons (1956-59), the repetitive structure of the cells was expressed physically and symbolically in pre-cast facade units, while the public rooms were more freely articulated in-situ; in the Unité d'Habitation, Marseilles (1946-52) the substructure in beton brut is almost zoomorphic. The public buildings in Chandigarh (1950-64) were made entirely in-situ with the lowest possible technology.

The more lyrical and expressive nature of his post-war work did not exclude practical problems, however. Wallace K. Harrison wrote of his incredulity at Le Corbusier's proposal to put brise-soleils on his project for the United Nations building, New York (1947) - they would have resulted in insuperable problems with snow. Criticisms have been voiced that the brise-soleils of the Chandigarh buildings are also unsuitable for the dusty North Indian plain; furthermore, the massive concrete construction acts as a heat store as it is a single layer. Although much of the imagery of the buildings was derived from technical sources - such as the Hall of the Legislative Assembly from a power-station cooling tower - inadequate ventilation compounds the problems. On the other hand, the basic concrete construction of La Tourette has proved appropriate to the milder climate of the Rhone valley and the monastic life of its inhabitants.

In his last work, the little-known Heidi Weber Pavilion, Zurich (1962-66), Le Corbusier prefigured many aspects of the emerging 'high-tech' movement, with walls of interchangeable vitreous enamel panels and ready-made industrial fittings.

Despite his obvious technical shortcomings, the power of his imagery and the brilliance of his creativity, not least in the area of technology, mean that Le Corbusier is an architect to whom others will fruitfully return.

Thomas Deckker

London 2001

London 2001