Courtyard near the Rozhdestvensky Convent, Moscow

© Thomas Deckker 1989

The courtyard of a residential block. A sunny day.

A sudden shower of rain out of a blue sky caused us to take shelter in an entrance. Total silence. More than silence: stillness.

At that moment I could see how Tarkovsky saw.

Nostalghia

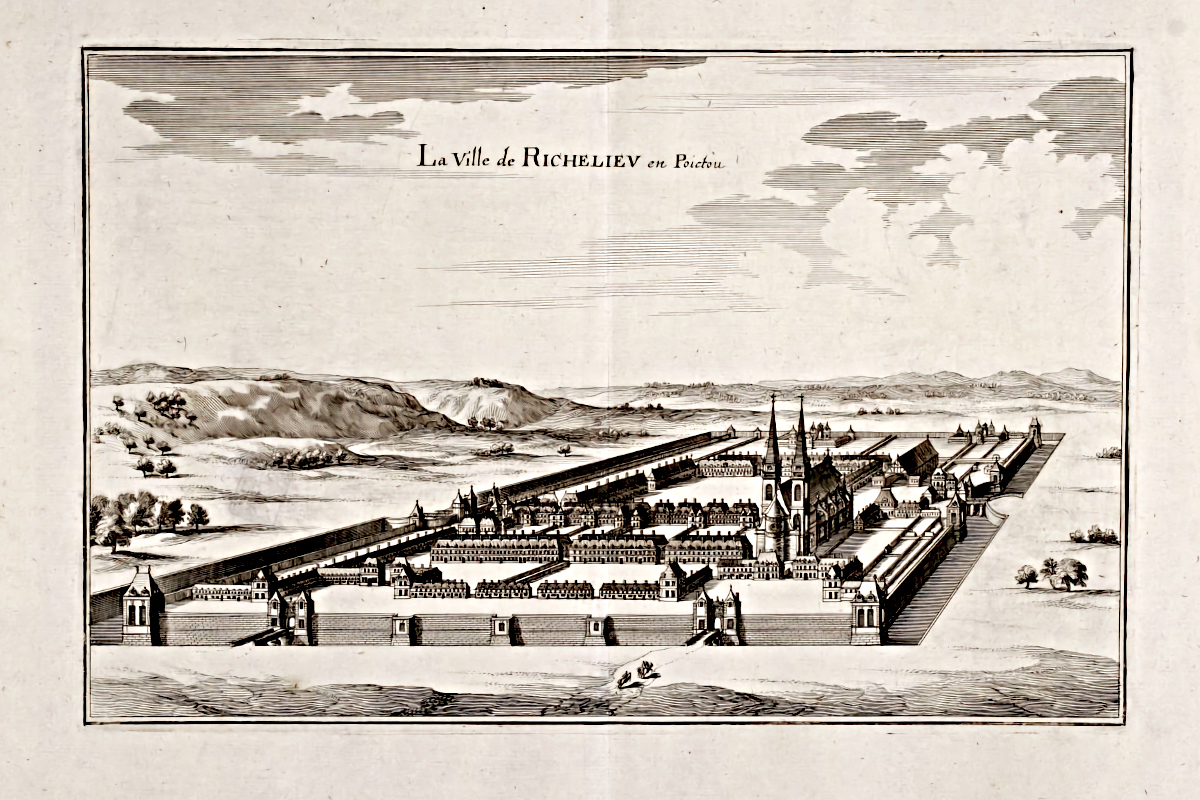

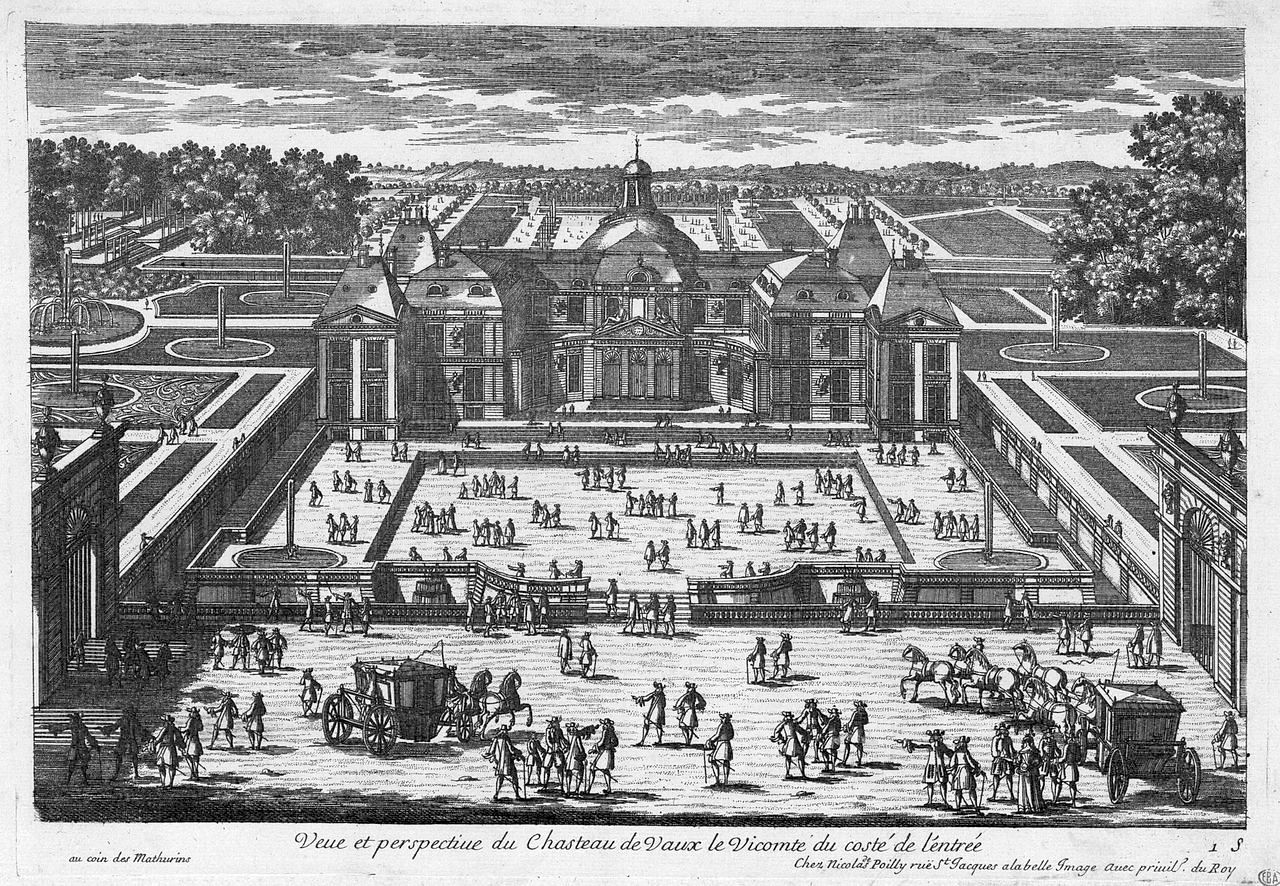

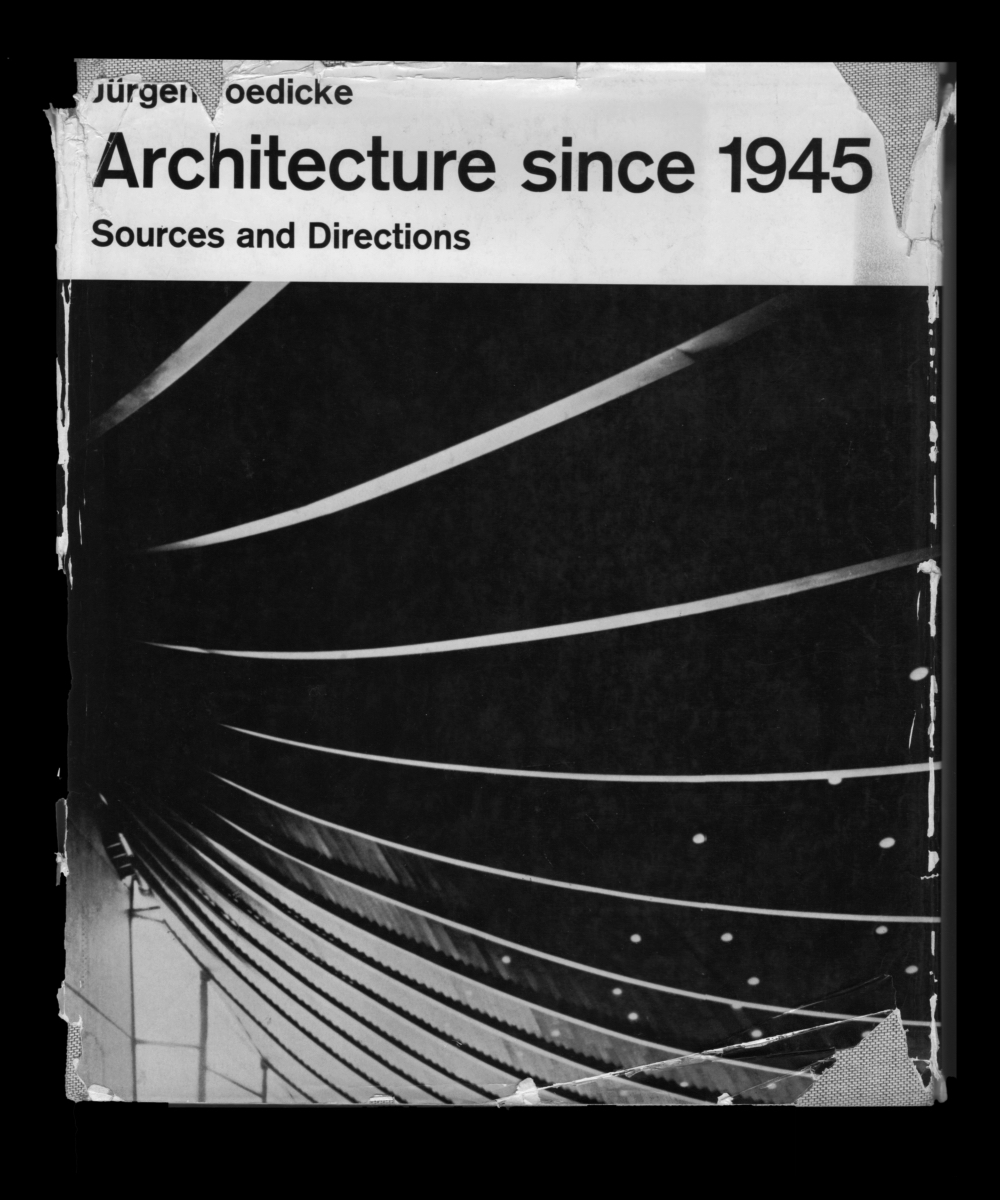

The title is a reference Nostalghia, a film by Andrei Tarkovsky released in 1983. The film is suffused with architecture and spaces that seem to exist outside any definite time, that exist across time and place. Nostalghia was shot in Italy, as Tarkovsky had been exiled from the Soviet Union, but the same charged spaces may be seen in his earlier film Stalker, mostly shot in a disused power station in Estonia.

But what could Tarkovsky have been nostalgic for? Certainly not the official city of military marches and brezhnevka apartment blocks. Before I went, I did not realise that parts of Moscow seemed to have been left over from an earlier time, or to exist outside a specific time including the present. It was a surprise to see buildings and spaces like these which had survived through the Soviet period. Whether they continued to survive after that is uncertain.

Staircase in a courtyard near the Rozhdestvensky Convent, Moscow

© Thomas Deckker 1989

The courtyards were unexpected. Somehow the informal and contingent interiors of the blocks coexisted equally with the formal street fronts. The strong shape of the - presumably zinc - roof over the staircase was compromised by the little window that cuts through the upstand. The wooden stair is like a rustic version of formal Russian architecture.

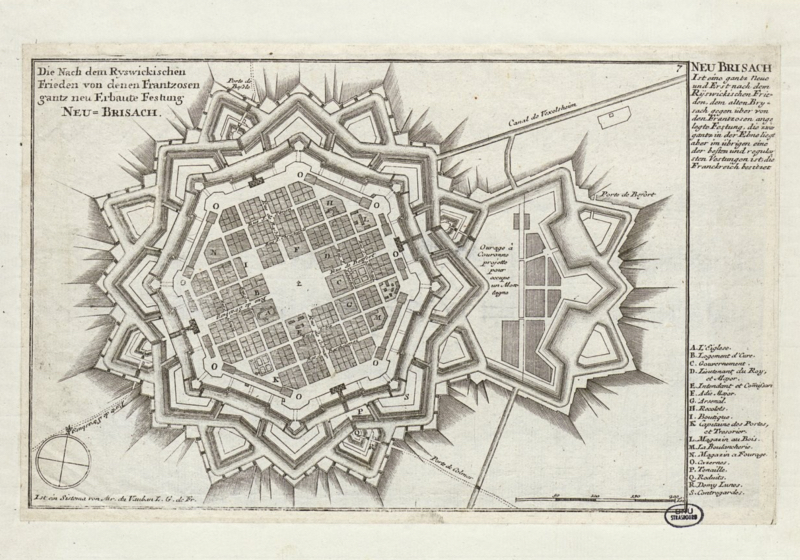

There is one thing curious about the streets: the Russian village plays hide-and-seek in them. If you pass through any of the large gateways - they often have wrought-iron gratings, but I never encountered one that was locked - you find yourself at the threshold of a spacious settlement whose layout is often so broad and so expansive that it seems that if space cost nothing in this city. A farm or a village opens out before you. The ground is uneven, children ride around in sleighs, shovel snow; sheds for wood, tools, or coal fill the corners, there are trees here and there, primitive wooden stairs or additions give the sides or backs of houses, which look quite urban from the front, the appearance of Russian farmhouses. The street thus takes on the dimension of the landscape.

[1]

a lane

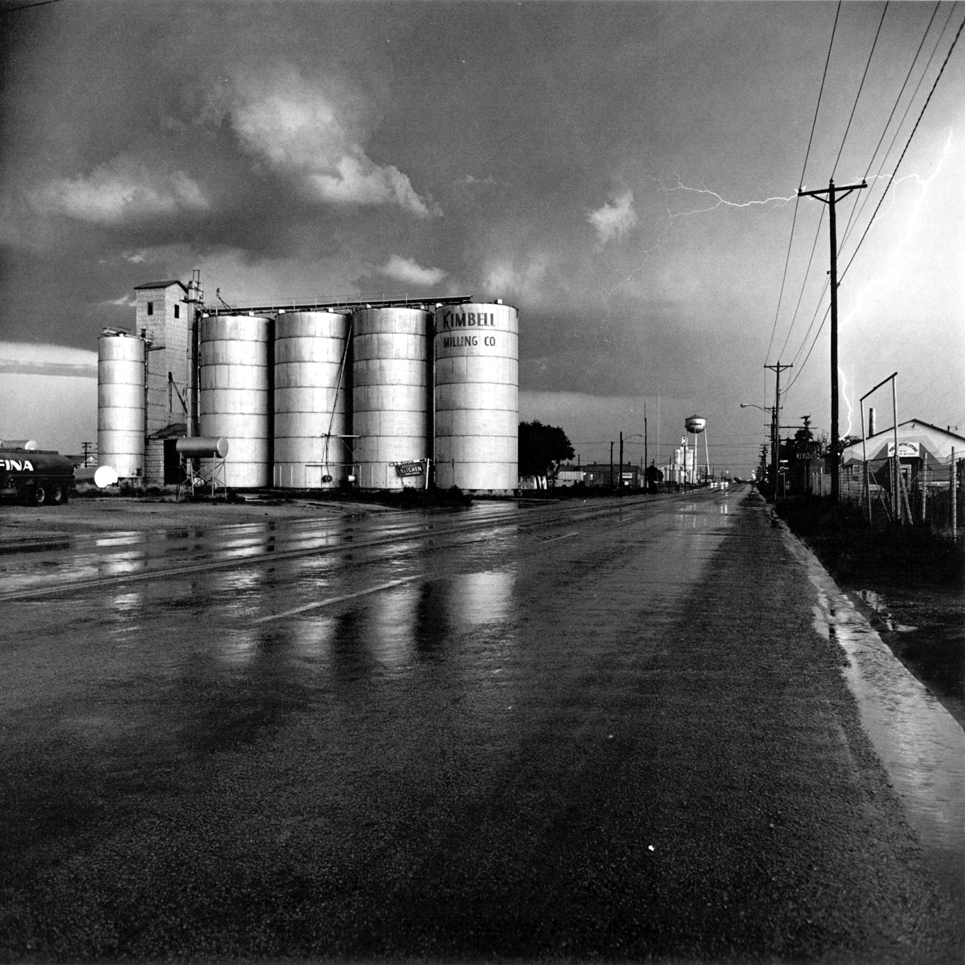

Lane near the Rozhdestvensky Convent, Moscow

© Thomas Deckker 1989

A beautiful lane, mostly abandoned and derelict, and with the obvious feeling that it could not be defined by any time, and in fact could have shifted in time, whether from some apocalyptic future or from the beginning of industrialisation.

a window

Window in a street near the Rozhdestvensky Convent, Moscow

© Thomas Deckker 1989

A window - in a building obviously later - in the style of the late-17th-century Naryshkin Baroque seen from, and apparently oriented towards, a narrow gap between two very humble buildings. The gesture is out of proportion to its situation and all the more moving for it.

a wall

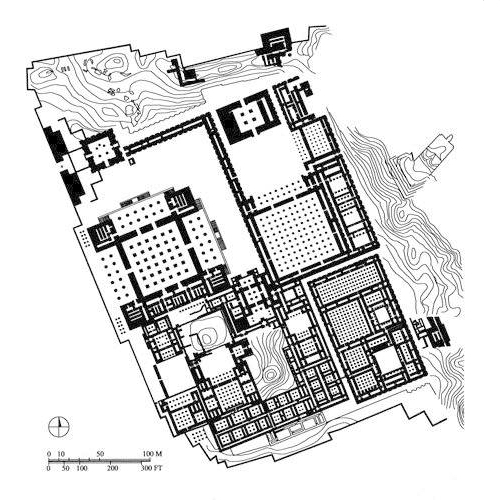

Wall, Novodevichy Convent, Moscow

© Thomas Deckker 1989

The sense of history was palpable in this wall, part of the Novodevichy Convent. Not only could a distinction be seen between the thick defensive walls of the 16th century and the more regular and less defensive 17th century constructions, but the irregular openings give a sense of plans made and broken, and of necessity overriding order.

a villa

Villa, outskirts of Moscow

© Thomas Deckker 1989

The isolation of this villa was reinforced by its proximity to Moscow, in fact on the road to Sheremetyevo Airport. It seemed a rural counterpart to the empty spaces of the Soviet city.

On the right side of the avenue that the street car was following there were occasional mansions, on the left side were scattered sheds or cottages, open field for the most. the village character of Moscow suddenly leaps out at you undisguisedly, evidently , unambiguously in the streets of its suburbs. there is probably no other city whose gigantic open spaces have such an amorphous, rural quality, as if their expanse were always being dissolved by bad weather, thawing snow, or rain.

[2]

Footnotes

Thomas Deckker

London 2025