It is a common-place assertion that the works of certain contemporary artists such as Donald Judd - rows of concrete boxes in a field in Texas - Richard Serra - a group of steel plates in a warehouse in New York - and Michael Heizer - a series of excavated trenches in the Nevada desert - are architectural. While this pedigree has often been self-consciously appropriated for the fashionably bare interiors of restaurants and art galleries, there is a more profound level at which this work can be interpreted as architectural: it offers a view of what, in architecture, might be appropriate for the conditions of the modern city.

The most immediate similarity between these works and architecture is that their forms and construction are similar to the forms and construction of buildings (or works of landscape architecture). Since the 1960s, these artists have moved from making works in galleries to working directly with large-scale objects and land. These works usually involve contractors - other people and machines - a method of working which is outside the bounds of what is thought to be appropriate for sculpture, but which is usual in the production of buildings.

These artists use large areas of land not only as the raw material from which their works are made but also apparently as the subject of their work. The idea that the content of a work can be the relationship of object to site is also outside the bounds of what is thought to be appropriate for sculpture. Sculpture is thought to contain a definite set of associations, implicit in its forms, that, to a large extent, justify those forms; they are commonly said to represent something. These works do not seem to represent anything but the facts of their location and construction; for this reason, they were initially widely criticised as nihilistic. But to look for associations misses a vital point of their conception: that they were meant to be physically experienced and enjoyed. That a work of art consists of the experience and enjoyment of the architectural (or landscape) space in which it sits is certainly a novel concept in contemporary art.

What makes the connection to architecture easier to comprehend is that some architects have become less concerned with the making of single buildings and have become more interested in making relationships between buildings and sites. They would deny that there is a common basis of understanding between architect and public which can be communicated through form; instead, they propose that buildings be physically experienced and enjoyed. Rather than designing buildings with recognisable images, they try to make buildings form new places in urban fabrics. This has often blurred the boundaries between architecture and landscape architecture, as both the building and its site are necessarily designed simultaneously.

The art historian Rosalind Krauss described some of the connections between architecture and sculpture in 'Sculpture in the Expanded Field'. Krauss argued that the word 'sculpture' had a definite meaning ascribed to it from within our culture, which could not be expanded to fit contemporary work. She contrived a dialectical grid of 'architecture' and 'landscape' with their opposites 'not-architecture' and 'not-landscape'; this split what is generally called 'sculpture' into four areas: 'sculpture', 'site constructions', 'site markings', and 'axiomatic structures'. 'Site constructions', such as 'Shift' (1970) by Richard Serra - a series of steel plates set into a sloping field -, were positioned between architecture and landscape; 'axiomatic structures', such as '100 aluminium cubes' (1967) by Donald Judd - 100 similar aluminium cubes -, between architecture and not-architecture; and 'site markings', such as 'Five Conic Displacements' (1969) by Michael Heizer - tyre tracks in the desert -, between landscape and not-landscape.

Krauss was the first critic to make a positive framework for understanding this kind of art, as opposed to other critics who labelled it 'minimal'. She restricted the definition of 'architecture' to the construction of space, in contradistinction to 'not-architecture', the construction of machines. By concentrating on the structural correspondences, however, Krauss neglected the radical political and aesthetic nature of the rediscovery of landscape.

Surprisingly, perhaps, the works of these artists came out of a reaction to profound changes in American cities during the 1960s. One group of artists, including Donald Judd, Richard Serra and Michael Heizer, and others such as Carl Andre, Tony Smith, Robert Morris, Nancy Holt and Dan Graham, were associated with Robert Smithson in New York. Smithson was a key figure in the group, until his death in 1972, because his mix of disciplines - land art, photography, performance, writing - was seen as a reaction against regarding art as a commodity (it was also, to some extent, a deliberate reaction against the New York art scene dominated by Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Barnett Newman), and because his work was inseparable from its critical stance on American culture. There was a parallel group - James Turrell and Robert Irwin - around Ed Ruscha in Los Angeles, who portrayed its extraordinary suburbanity in works such as Twenty-six Gasoline Stations (1963) and Thirty-four Parking Lots in Los Angeles (1963).

For Smithson, the Meadowlands, New Jersey - the industrial hinterland of New York - was a critical site: a technological dystopia, rather than a technological utopia. The Meadowlands had suffered particularly in the changing economy of the 1960s, as its heavy industrial base declined and its proximity to New York made it suitable for dormitory suburbs. On the one hand, it was a landscape of decaying industrial structures from the early part of the century and, on the other, new 'tract housing' developments - very-low-cost mass-produced housing - and their accompanying infrastructures. Smithson described it as:

a kind of rotting industrial town where they were building a highway along the river. It was somewhat devastated... New Jersey is like a kind of destroyed California, a derelict California.

The Meadowlands became a major area of interest for all these artists, especially after Smithson began work on 'Monuments of Passaic' (1967), a photographic study in which he showed decaying industrial objects (and unfinished infrastructure) and the declining town. The banality of the 'tract housing' developments - rows of identical houses with a 'choice' of colours - was satirised by Dan Graham in 'Homes for America' (1968). Carl Andre worked there in the railway yards. Tony Smith drove along the unopened New Jersey Turnpike at night to experience the seriality of modern roads. Donald Judd and Robert Morris explored a strip-mine in Passaic with Smithson and his wife Nancy Holt in 1966.

Smithson's work was widely known, and his photographic studies - exemplified by 'Monuments of Passaic' and 'Proposed Mining Project' (1972-73) - were enormously influential on American photography in general: what came to be called The New Topographics or, ironically, The New American Pastoral. In The New American Pastoral, David Maisel illustrated photographs of strip mining such as 'Open Pit Copper Mine' (1985); Patricia Bazelon recorded decaying industrial architecture such as 'Lime Silo and Lake Erie' (Bethlehem Steel Mill series 1988). Measures of Emptiness by Frank Gohlke was an exploration of the material quality of grain elevators and their relation to the prairie landscape. Phyllis Dearborn Massar, in the survey of contemporary photography Landscape/Cityscape, remarked that American photography had moved from the 'heroic' portrayal of landscape to showing Paterson, New Jersey, which she described as:

bleak physical decay, mass-produced stereotyped environments, suburbanized and industrialized former farms, over-used and overrun parkland.

This new perception of the material qualities of industrial architecture and landscape had particular relevance to Modern architecture in which industrial structures - especially grain elevators - had often been idealised. Le Corbusier had illustrated American grain elevators, heavily retouched to reduce both ornament and signs of weather, in Vers une Architecture. He believed them to be primary forms in unison with universal order. It was necessary that they were juxtaposed against a 'natural' landscape. This attitude may be exemplified by the Villa Savoye (1929-31), in which he used forms derived explicitly from grain elevators, as well as primary geometries; he regarded its multiplication on the Argentine pampas as a 'Virgilian dream'. However, in A Concrete Atlantis, the historian Reyner Banham exposed the reality of these objects as based on material and processal requirements (not on abstract ideals of geometry), and illustrated their present (decayed) condition with photographs by Patricia Bazelon. A Concrete Atlantis was as much a symbol of the end of Modern architecture as any other publication.

There was another opportunity engendered by changing circumstances in New York, however, and one which signified a shift from observation to creation. A large part of the Lower East Side of Manhattan had been virtually abandoned during the 1960s by the businesses who occupied it because of the threat of the construction of the Lower Manhattan Expressway, a major crossing of the island at the level of Hudson Street, by Robert Moses, the Commissioner of New York. A whole type of space became available for artists to use: the warehouse, large empty floors with powerful spatial and material characters often lacking in galleries. Because of the size and nature of these spaces, they seem often like internal landscapes. These buildings, with prefabricated cast iron fronts, constituted an unpretentious and anonymous urban architecture; they became not only the studios but also the living spaces for artists: Judd bought 101 Spring Street in 1968, soon after the abandonment of the Expressway proposal in 1965.

A subtle change in direction soon began to mark the work of some of the artists who used these spaces: they began to exploit the spatial and material characteristics of the warehouse spaces in their work. 'Scatter Piece' (1967) by Richard Serra, for example, consisted of waves of molten lead thrown onto a warehouse floor. Whether in internal or external landscapes, these artists began to explore the nature of an art that was contingent to its site - a parallel can be drawn between 'Scatter Piece' and the now-lost 'Displaced/Replaced Mass' (1969) by Michael Heizer - rocks tipped from a moving truck in the Nevada desert.

This was a radical departure from what had been considered sculpture until then. Much of the early work of these artists had been intended for the gallery; there was a similarity among works such as 'Untitled' (1963) - a red box with a steel tube on top - by Judd, 'Untitled (Four Mirrored Cubes)' (1965) by Morris, and 'Four to the Wall' (1969) - steel plates with a lead tube on top - by Serra. While some of these artists - Robert Morris, for example - were content to let their work remain in the gallery, for Judd and Serra the new sense of contingency to the site, whether internal or external landscapes, was vital to the direction their work took.

There was a further reason for these artists to be attracted to the idea of working with landscape. In 1964, the Museum of Modern Art, New York held an exhibition on 'Twentieth-Century Engineering'. Much of the work at the exhibition was civil engineering: highways, dams, and bridges, at the scale of the landscape. Judd reviewed the exhibition and wrote that much of this engineering was better architecture than architecture itself. He admired the grain elevators and industrial sheds, but thought much of the contemporary architecture was 'consumer junk'; two exceptions were the 'City Towers Project' (1956) for Philadelphia by Louis Kahn and the corrugated sheds of the Gold-Zack Factory in St. Gallen in Switzerland.

These artists soon began to experiment with exactly the sort of construction they could see in this exhibition: large-scale works either on or in the land. Geometrical form began to appear in 1966: a drawing by Robert Smithson of a 'Cube in Seascape', 'Afrum-Proto' - a projected light piece, also apparently a cube - by James Turrell, and 'Equivalent VII', a brick assembly by Carl Andre. Much of what became known as 'land' art emerged from these works: 'Double Negative' by Heizer in New Mexico (1969), and 'Spiral Jetty' by Smithson in Utah (1970). The West was chosen for the pragmatic reason that land was cheap: they often used disused industrial land.

In much the same way as Banham's A Concrete Atlantis, with photographs by Patricia Bazelon, indicated the end (at a theoretical level, at least) of the attitude of geometrical form as an ideal and universal contradistinction to landscape, the work in the landscape of the American West was contingent upon its site. There was no intention that the cut through the canyon in 'Double Negative', for example, be seen as an ideal alternative to its site: it was a celebration of the blasting out of the cut thorough the rock, of the space and light of the desert, of a man-made cut playing against the natural boundary of the mesa.

These concerns are epitomised, in many respects, by the work of Donald Judd in the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas. Judd had started his career on the boundary between art and architecture and never relinquished his interests in architecture. Judd intended to bring aesthetic experience into all levels of life - from landscape to architecture to furniture; although he continued to make - and sell - works for galleries, the Chinati Foundation became a kind of gesamtkunstwerk.

Marfa is the county seat of Presidio County, Texas. Its main industry was ranching (the film Giant was shot here in 1956), but this declined. It is claimed that Judd first saw the town from the railway as a recruit in the US Army in 1946; the closure of the railway was symbolic of that decline. Judd became a major employer in Marfa, both directly and indirectly, not only through his estate but through his activities as a cabinet-maker in El Taller Chihuahuaense. The former ranching community has adapted well to being supported by Judd, although some aspects have been quite controversial; one article in the popular press put it as 'Donald Judd: What's this artist-anarchist-philosopher doing in Marfa, Texas''.

Judd renovated various buildings in Marfa, such as his own house, the Mansana da Chinati, the Chamberlain Building, and the Marfa Bank which became his architecture studio, and subsequently others outside the town, such as the Ayala da Chinati, and Fort D. A. Russell, a former US Cavalry barracks, which became the Chinati Foundation. Judd bought Fort D. A. Russell in 1979 with sponsorship from the Dia Art Foundation, a foundation endowed by the Menil family, perhaps best known for the Menil Collection in Houston. The barracks were used for accommodation and for gallery space; the Arena became the living room; the Artillery Sheds became the home of '100 mill aluminium works' - a series of 1-metre aluminium cubes, while the parade ground became the site for the '15 concrete boxes' - groups of 2-metre concrete cubes.

Taking the works out of the gallery brought personal experience into its appreciation. Marfa is in West Texas, where there are extremes of heat and light; all the senses are necessarily involved. One of the strangest experiences is the deep silence in the Arena broken by the thermal expansion and contraction of the corrugated steel roof in synchrony with the light and shade of the clouds. While in a gallery these might be a distraction, in Marfa they are an essential part of the work itself.

Judd saw his buildings in Marfa not simply as repositories for his art works but as an alternative to contemporary American preoccupations with architecture and landscape. He thought the development of the 'strip' responsible for the destruction of the American city, a product of 'Big Business' rather than an authentic vernacular. Judd was quite explicit in his criticism of buildings such as AT&T (Philip Johnson 1978-84) in New York: on the one hand, the attempt at social signification through its classical image, and on the other, the reduction of physical experience - the crude detailing of materials, the bland interior spaces and gestural public areas.

Judd disliked not only the dissolution of American cities, but also the colonisation of the landscape. Although the open spaces of the American West are thought of (and depicted in Western films) as the archetypal frontier, with the decline in ranching the public have no access to or interest in the land, as Judd observed:

In West Texas there's a great deal of land but nowhere to go. The land is closed to the people from the towns. There are no parks with facilities. On the other hand, as small as the towns are, most of the people are urban and are not interested in the land. They seem afraid of it and hostile to it, and if allowed, they attack it. He thought this colonisation was effected by the free-standing house, which he thought suitable only: for camping, for a house in the country, for a hunting lodge, a boat-house, a dog-house, but... a disastrous principle for a modern city.

Judd's buildings in Marfa can be seen, therefore, as an alternative proposal for American architecture. He believed that houses in the country, such as the Ayala da Chinati, should have enclosed space to protect them from the climate, and also, paradoxically, in the city, such as the Mansana da Chinati, to give light and outdoor space. In opposition to normal American practice, he liked the renovation of buildings (which was fortunate as his new works at the Foundation were not successful and were abandoned):

In the present century of the destruction one way or another of cities and land, preservation, conservation, and restoration have become some of the most necessary and positive and unlikely acts.

This work is obviously closely linked to the work of architects such as Louis Kahn and the Mexican architect Luis Barragan who stood outside mainstream conditions of practice. Many of Judd's early architectural drawings looked like the work of Kahn, such as the sketches for Arroyo Grande, a house in Mexico from the late 1960s, and for 101 Spring St., for which he proposed a circular staircase like Kahn's Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven (1950-54). His later work, however, reflected more the influence of Barragan. Not only were the modest and simple volumes of Judd's houses similar to Barragan's, but also his landscape designs to works such as Las Arboledas (1958-61).

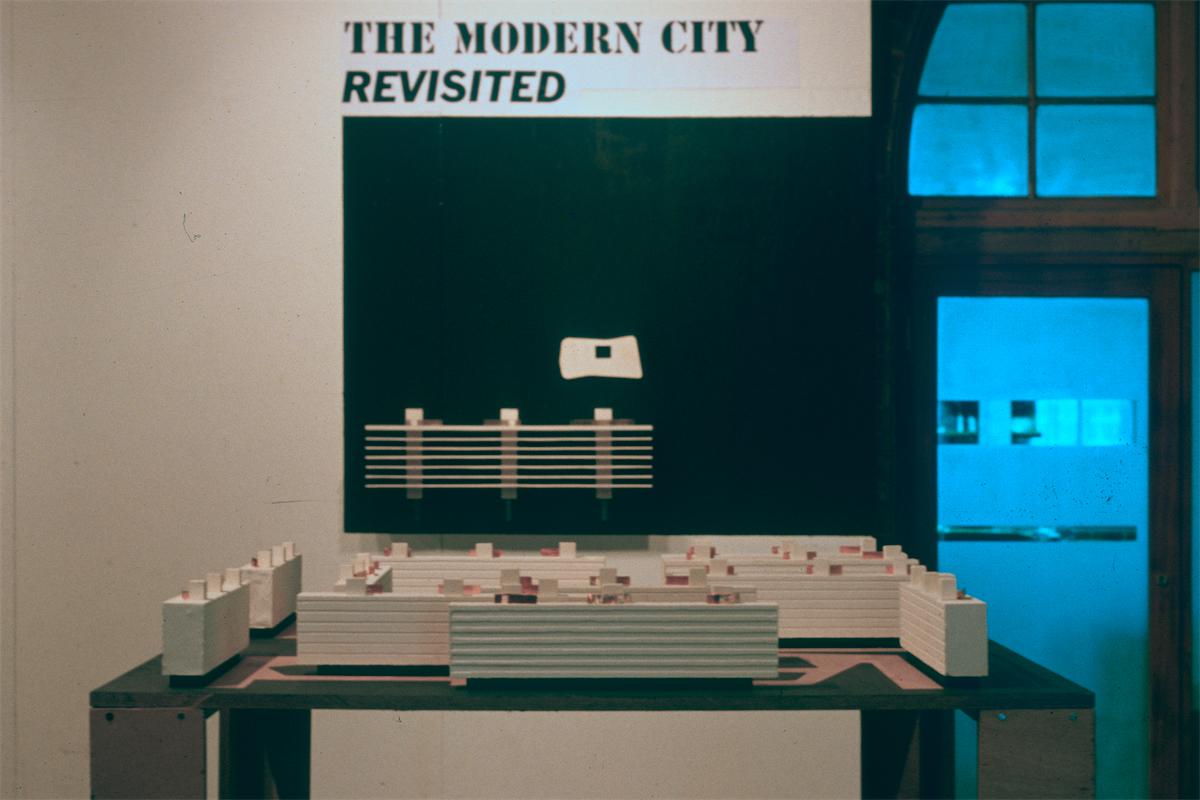

After the completion of the major works at the Chinati Foundation, Judd was invited to propose urban projects in several cities in Switzerland - Winterthur and Basle - and Austria - Bregenz (Judd lived part of the year in Eichholteren, near Lucerne, where his aluminium pieces were manufactured). His major opportunity was when he was invited to collaborate on the Post Office Railway Station in Basle in 1993 by the architect Hans Zwimpfer. Zwimpfer was already a major architect in Basle; he had worked with artists such as Hans Arp, Alexander Calder, Joan Mirô, and Tapies in the 1960s. Rather than put a piece of public art on the site, Zwimpfer chose to invite Judd and other artists to work on the planning of the building; he did not want a 'decorated object'. Of the budget of CHF500m [£208m], CHF3m [£1.25m] were for various art projects involving the building.

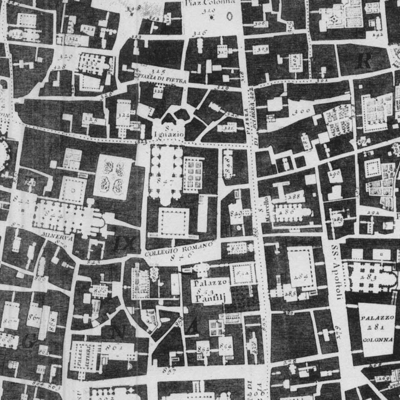

The Post Office Railway Station was commissioned to meet the current requirements of an industrial city on the border of France, Germany and Switzerland: it houses not only the Post Office Railway Station, but a customs post, the headquarters of the digital telephone network, a car park, and a large amount of commercial office space. It is situated behind the main railway station, the HauptBahnhof, on the edge of the historic city, in former railway marshalling yards. Basle is under intense pressure to house the industries which constitute a significant part of Switzerland's economic base, without destroying its well-preserved historic centre.

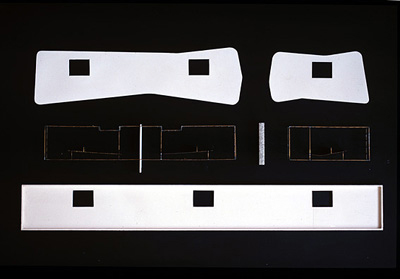

The design of the Post Office Railway Station, however, is quite different from most speculative office buildings: it is a low-energy building, mostly with natural lighting and ventilation. Judd was instrumental in the design of this building and the integration of these environmental features; his main contribution was the form of the building as a series of linked pavilions on a podium over the railway tracks. The podium forms a public passage, with cafes and shops; the pavilions facilitate natural lighting and ventilation by breaking down the mass of the building. But the most significant feature is that there is no attempt to make the building 'contextual'; the serial forms of these pavilions appear remarkably like the serial forms of his work in Marfa.

There is something particularly appropriate about the transfer of the design principles of 'land art' from the American West to European cities. The changes that occurred in New York in the 1960s and produced the Meadowlands epitomised the changes that occurred increasingly in all cities. If the 1960s was a significant period in cultural history, it was also one in economic history; it was when the phase of 'late capitalism' is held to have come into being by writers such as Frederic Jameson, David Harvey and Edward Soja. In the 1960s, capitalism entered into a period of stagflation which led monolithic Taylorism to be abandoned in favour of 'flexible accumulation' in the 1970s.

In the period of 'flexible accumulation', the production of culture became integrated into the production of consumer commodities in general. Information became a central concept. The economy of images not only overtook the importance of building but became central to architecture itself, symbolised by the publication in 1972 of Robert Venturi's Learning from Las Vegas. Society seemed to require buildings that were signs of buildings, as may be seen in Venturi's diagram of a casino: a large empty box with a sign on front (or as the 'tract houses' in the Meadowlands were 'signs' of houses). Of course, the interiors of these buildings had no spatial or material qualities.

The decline in urban architecture throughout the post-war period had particular relevance to European cities, which have been seen as the locus of a particular type of urbanity (as much as the American West was seen as the locus of particularly 'American' values). City centres have become increasingly conserved, while the sites of former industry, in particular on the periphery, have become the site of maximum expansion. In other words, the Meadowlands - railway yards, left-over spaces around roads and the suburbanised countryside - has become an universal urban condition. It is exactly this type of place which is the site of the Post Office Railway Station in Basle.

Architects themselves had been playing an increasingly reprehensible role in the impoverishment of the environment, especially the city, during the post-war period. On the one hand, the theoretical basis of architecture itself, such as functionalism, led to a reduction of physical experience, and on the other, practice became dominated by technical and processal objectives, such as low-cost production methods, which denied any value in the relationship to context. These aspects worsened as architecture lost its utopian drive. The populist reaction in the 1970s simply reflected and encouraged the ethics of 'late capitalism'; 'contextualism' is used to disguise or even deny the colossal impact of development and its problems.

For other architects, however, the definition of a contemporary urban architecture has become a central concern, especially for this new type of site. A return to traditional forms is not considered appropriate, nor in many cases even possible, on these sites. In opposition to this mainstream practice, two guiding principles could be stated: that the building should not be a sign of itself, but have definite material and spatial qualities, and that its form should create new urban spaces within the context of the existing site, as may be seen in the Post Office Railway Station. One can invert the opening statement and say that it is in this way that the work of certain contemporary architects has its aesthetic parallel in the work of 'land' artists.

thomas

deckker

architect