There are 8 relatively small Schools of Architecture in London, each competing for Government funds and for the best students. The weapon that these Schools employ is the 'Unit System'. The Unit System was introduced into architectural education in Britain in 1972 by Alvin Boyarsky at the Architectural Association. It replaced the teaching methods stipulated by the Oxford Conference in 1958 which established modern architectural education in British Universities.

The Unit System at the Architectural Association produced, between 1972 to 1988, an extraordinarily influential group of architects who occupied an unequalled international position. It proved easy to introduce into the Architectural Association, a private institution, because its unique constitution empowered students to elect their teachers to the School. The success of the School, therefore, reflected directly the success of the teachers. On Boyarsky's death, there was diaspora of students and teachers into other British Schools which simultaneously enfeebled the Architectural Association and gave international profiles to other London Schools. The Unit System is now widely used in Schools in Europe and the United States.

This diaspora coincided with a Government policy to massively increase the number and size of British universities, which meant that Schools of Architecture were able to expand staff and student numbers dramatically. The Government initially tied funding to student numbers only, which gave Schools the incentive to increase these as much as possible. It was further facilitated by changes to contractual conditions of employment, which abolished academic tenure and sanctioned part-time employment of teachers in universities. The result of these two factors was to raise schools from their previously stagnant positions into very dynamic and competitive institutions.

The most critical factor in the widespread success of the Unit System was that it did not assume, as the Oxford Conference had done, that there was an objective and rational process to architectural education or even architecture itself: it proposed that architectural education take place through the formation of personal interests and judgements. It aimed to teach students how to think, architecturally, and left construction and professional education to the office and building site. This suited architectural education in Britain well, as students graduating with Diplomas are required to work for 2 years in an architectural practice and sit a further exam, Professional Practice, before registering as architects.

Paradoxically, the Unit System was a continuation of the teaching system evolved during the nineteenth century at the ɉcole des Beaux-Arts. It is no coincidence that Charles Jencks, himself a teacher at the AA, proposed that Modern architecture died in 1972. The teaching programmes at the AA were all alternatives to Modernism; in many cases they defined the alternatives to Modernism in the late 20th century. More serious critics such as David Harvey also proposed 1972 as the year that the flexible and pragmatic neo-liberal global economy began to replace supposedly rational but monolithic national economies.

The essence of the Unit System, in theory at least, is that the best teachers of architecture are not academic 'professors', but practicing 'architects'. In the Unit System all teachers work part-time at the University and usually combine teaching with practice. Each teacher conceives, administers and assesses a programme for the year; he or she is responsible for administering a budget for materials, travel, technical teachers and critics. Each programme represents an unique approach to architecture which students elect to follow at the beginning of an academic year. A certain amount of technical and historical knowledge is taught directly in lectures, but the main teaching of architecture mimics directly the process of an architect in proposing responses to a problem, or even defining the problem in the first place: research, attitude, development.

Projects are introduced and discussed in seminars and assessed in juries, usually with invited critics and specialists from outside the school. The main part of the teaching in the Unit, however, takes place in individual tutorials. Students receive 1 hour of personal tuition per week in which their projects are discussed in depth. In this way, students work within an area of interest set by the teacher, but the specific parameters of the problem may be set by general agreement in the Unit and individual directions may be set in personal tutorials. Students then present and defend their projects publicly before fellow students and critics. Marks at the end of each academic year are assessed by fellow teachers and external examiners to ensure equality of ambition and achievement across the Units.

The Unit system is intended to contain a compensation for the disadvantages of part-time contracts - low pay and no tenure - for the teachers: it is intended to allow young architects to develop individual experimental approaches to architecture outside the realms of commercial practice and distinct from the purely critical and theoretical concerns of academia. The Unit would thus be a kind of laboratory for ideas, rather than a system to impart normative solutions. It is expected that teachers pursue lines of research outside the School: through publications and the construction of buildings.

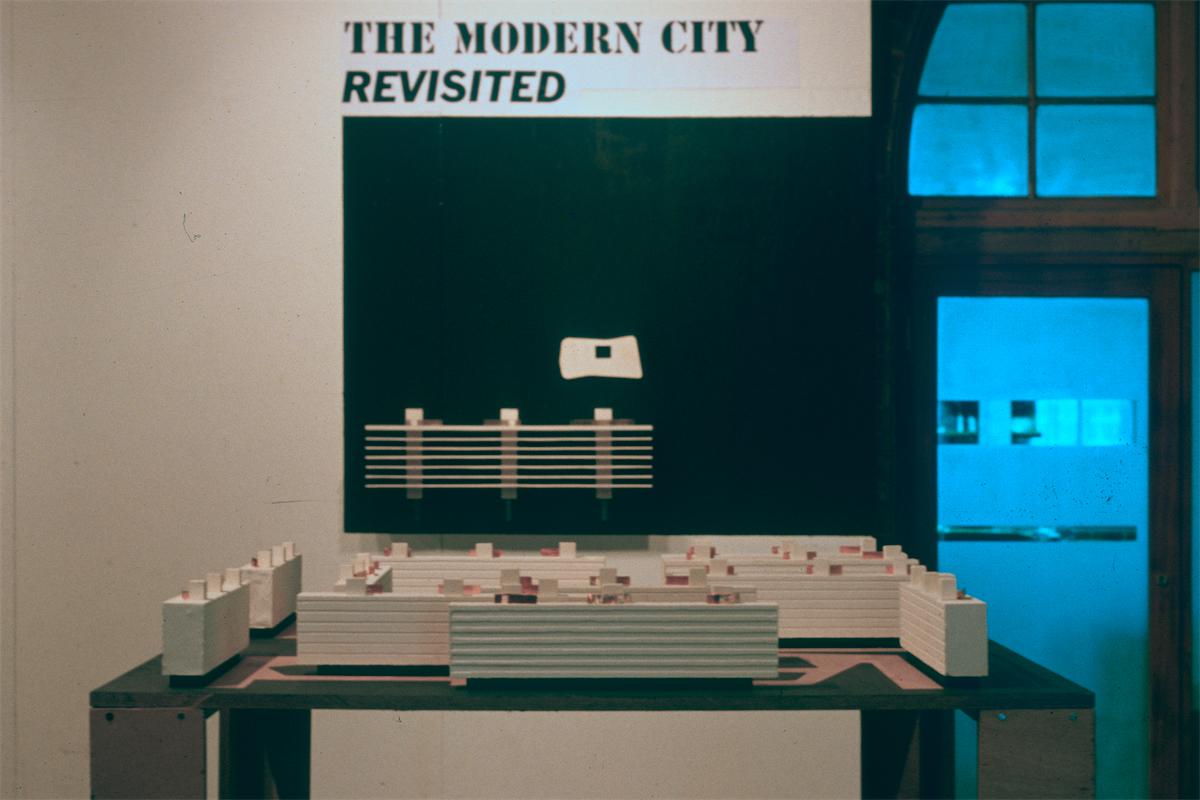

My teaching programme at the University of East London was considered an integral and important part in raising the profile of a marginal School to one of central importance among London architectural Schools. It became a laboratory to develop ideas of the relationship of architecture to site, in particular urban sites, and the relationship of architecture to urban processes. Students in the Unit developed methods of working at theoretical and practical levels which they could then apply to the formation of approaches to urban and landscape design and to the design of buildings.

The Unit System also required a methodology of education distinct from any particular architectural direction. My methodology was that both architecture and the teaching of architecture should be based on individual experience. It was quite explicit in the approach that students (and their teacher) should experience architecture and, in turn, make an architecture of experience. The Unit deliberately sought out experiences of urban or landscape contexts and the work of architects whose work had an experiential basis, and it sought to represent design in those terms. A wide range of material was used to present projects - photomontages, collages, sketches, drawings and models. I had no real interest in typological or functional approaches; in fact, they were seen as an inheritance of the old educational system rather than as possible solutions.

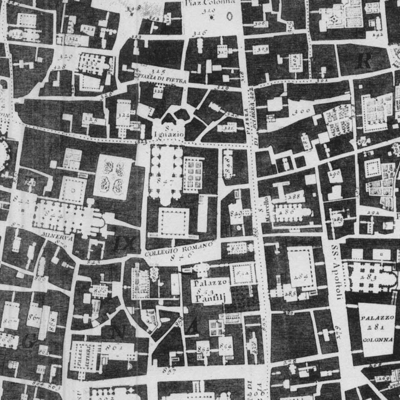

The problems we were principally concerned with in the Unit were how space may be structured, the interdependence of landscape and architecture, and the relationship of architecture to its use. A year was structured around a series of projects and a two-week Unit Trip. The first project - the plaster block project - lasted only 6 weeks, to examine ideas about architecture and landscape at a theoretical level. This led to either a single major design project or two smaller projects at different scales which lasted a total of 20 weeks.

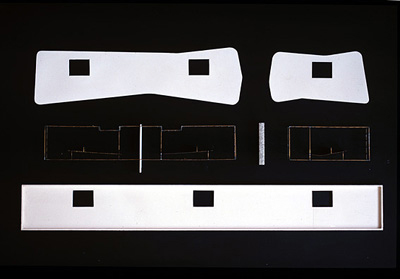

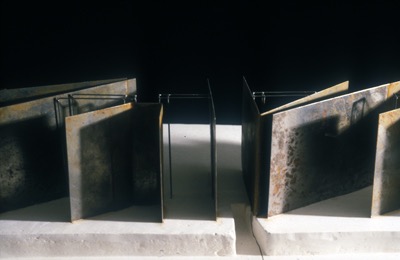

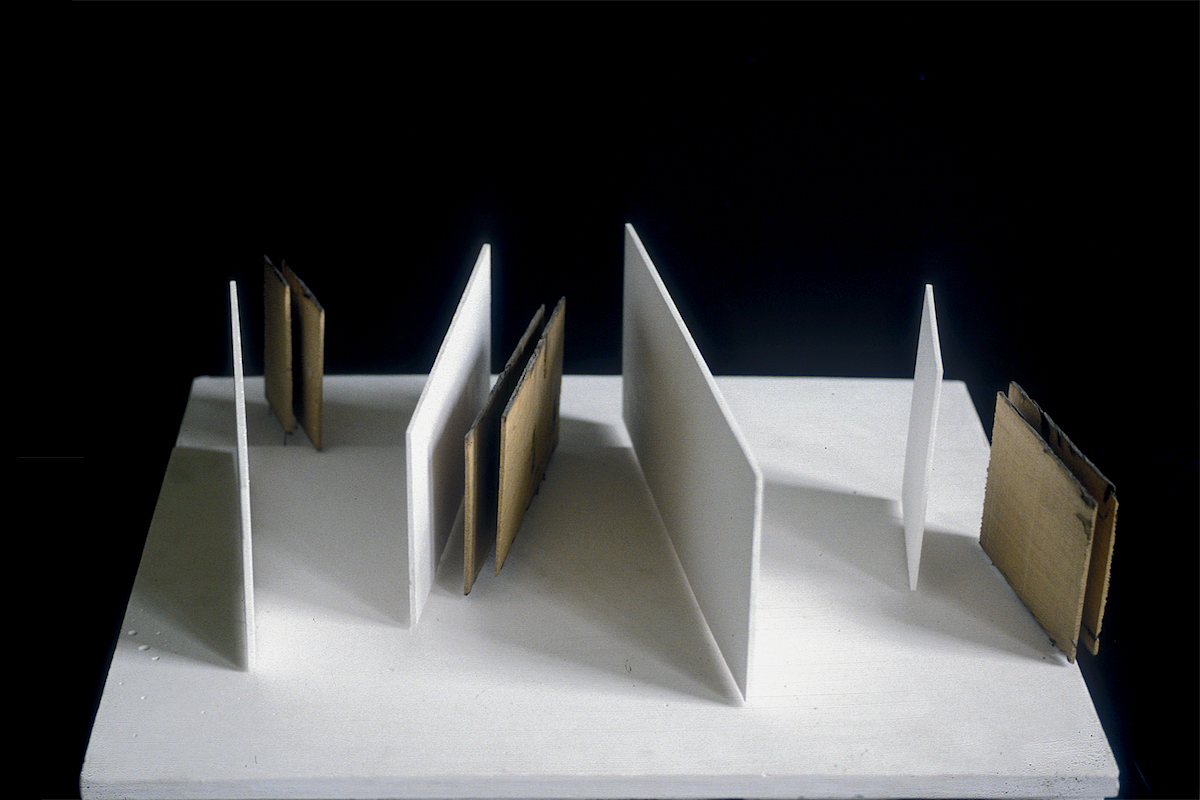

The course of the plaster block project was almost entirely directed by the students themselves. The brief given the students was to make a plaster block which represented landscape and add something to it which represented architecture. This involved many decisions which had to be made mutually: the size of block, how the mould should be made, and what exactly the project was about. They then had to think individually what constituted landscape and architecture. This project was presented to the students as a preliminary exercise in thinking and making, and the results were intimately associated with the processes of making. However, there were a number of more cerebral intentions implicit in the project: it was an exercise in the discovery of emergent form (when several systems of making result in a new form) and of determinate and indeterminate form (for example, making systems which result in unexpected form rather than forms themselves). At the extreme, landscape and architecture merged with each other. These concepts were important because they led the students away from designing independent form and into thinking about architectural form as related to context. But there was a major difference with the usual manner of making these studies: they were based on experience - making and observing, rather than as abstract systems of information such as on a computer. Many students maintained and developed a consistent approach throughout the year from the highly abstract plaster block project to design projects.

In the plaster block project one year, the students decided to work with smooth blocks of plaster. This implied that, in many cases, the 'landscape' would have to be determinate rather than indeterminate. Many of the most interesting projects thus played with the idea of inversion between determinacy and indeterminacy. One student made an observation of this inversion in the Palais Royal in Paris. She explored mathematical sequences of wires hammered into the block - a type of architecture - inspired by the music of J. S. Bach. These were then turned into a 'landscape' by covered them with plastic sheets to form a mould. This process continued until the complexity of sequence led to an indeterminate landscape. Another student drilled a regular grid of almost 600 holes into a block, and then poured molten lead over it, which dribbled through the block in an indeterminate way. One student (a fan of broken glass) drilled 1000 holes into his block, each holding a long fine wire fixed in lead which formed a new surface. A machine was made to drop steel balls onto it in a fixed pattern. The resulting destruction formed an indeterminate 'landscape' surface from the 'architecture'.

The Trip was a major part of the programme of the Unit. These trips were meticulously planned to allow us to experience cities, landscapes, architecture and art, and to share these experiences as a Unit. We generally visited important buildings and met important architects, and involved ourselves in experiences of urban form or landscape. These trips were not intended to be studies of precedent, as the buildings were not the same ones as the students would design in their major design project. Most importantly we travelled together and experience the trip as a group. Our most memorable trips have been to Portugal to study the work of Alvaro Siza; Switzerland, with stays at the Unité d'Habitation in Briey and La Tourette by Le Corbusier; Mexico, to study the work of Luis Barragan; and Texas, where the artist Donald Judd built the Chinati Foundation.

My interest in the work of Donald Judd resulted in the Unit Trip to Texas. Because of the length, complexity, and expense of the trip, meticulous preparations were made to ensure that we would be able to make the most of the opportunity: visits to two great buildings, meetings with architects, and plenty of experience of urban planning and landscape. A day in Ft. Worth - the Kimbell Museum by Louis Kahn - we cancelled all our plans for the rest of the day to make the most of the experience; a day in Dallas - a visit to the First Interstate Bank Plaza by Dan Kiley, chasing the water. We explored the disused stockyards in Ft. Worth and found Billy Bob's, the biggest night-club in Texas - we were the only black people there. We then drove 600 miles - an enormous distance to an European - to Marfa. On the way we discovered Lamesa (planned) and Rhodes Welding (unplanned) - driving mile after mile through cotton fields we suddenly came across a series of oil storage vessels which looked exactly like Le Corbusier's dictum: 'Architecture is the masterly, correct and magnificent play of masses brought together in light'. We stayed 4 days at Marfa, where we made studies of the work of Donald Judd - light - form - landscape: concrete block and aluminium pieces. We cooked and ate (and drank Donald Judd's wine) in the Arena every day. A trip to Big Bend National Park: we hiked into the Santa Elena canyon, within living memory the true wild west (at least on the Mexican side); we crossed the Rio Grande into Mexico by rowboat. We drove back via Austin and met Chris MacDonald who taught architecture at the University there. We toured the 17th century Missions in San Antonio. In Houston we met Carlos Jiménez and visited several houses in the Montrose district, and the Houston Museum of Fine Art Administration Building, his most well-known public building, with him. We made studies of car-parks in the Downtown and the former slave district. We then toured the Menil Collection by Renzo Piano, with an introduction and tour by the director. I lectured at Rice University on the work of the Unit. The afternoon was spent on the beach at Galveston. On our last night we went to a soul bar - we were the only white people there.

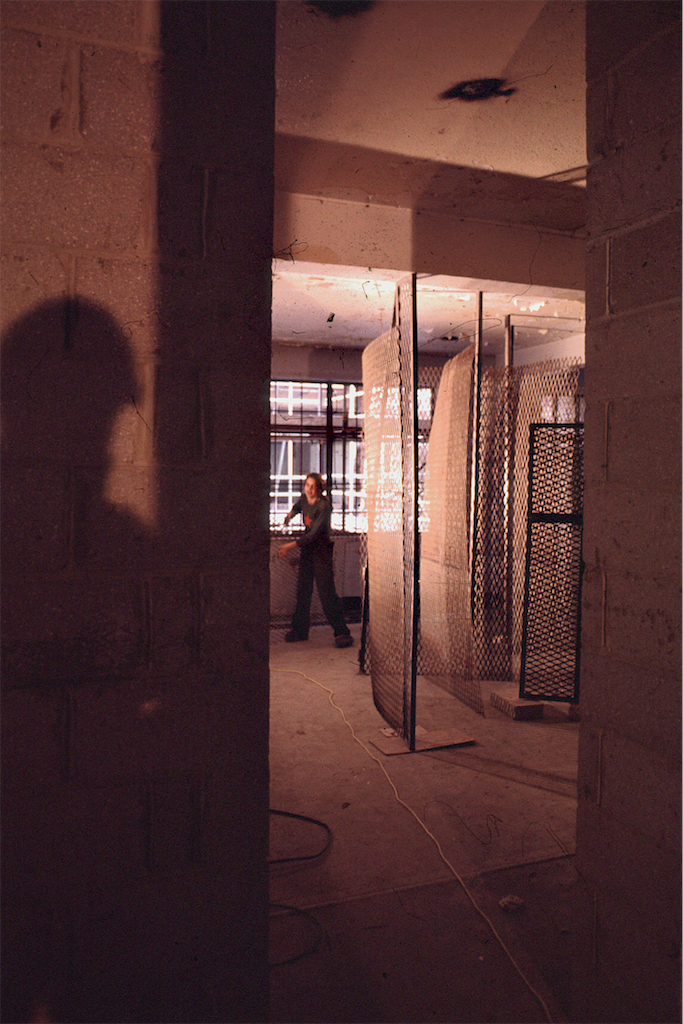

The main design project was usually one large building, involving a range of scales from urban or landscape design to a single space. It was intended that students carry through concepts they had learned from the plaster block project into the urban or landscape design and further into the design of individual parts of the buildings. For a project for a holiday complex in Sagres, students proposed structuring the landscape with paths and walls, and extending these structures of space and movement into the individual buildings. We explored similar themes of the relationship between landscape space and architecture in urban contexts: in projects for a mixed-use building in Deptford and for an arts building in the South Bank. The main design project was always rooted in various studies of use. For our project in Sagres, we behaved a little bit like tourists by recording our experiences of the trip. For design projects in London, we usually included a study of Soho, a shopping, entertainment and media centre, particularly for its combination of work and leisure. The serious purpose of looking at bars and theatres was that in these spaces the conventions of public and private spaces are challenged, with particular rules of behaviour and an infrastructure of thresholds and boundaries: doors, staircases and windows.

thomas

deckker

architect